The computer says no – electronic incapacity reports LiMA is the

advertisement

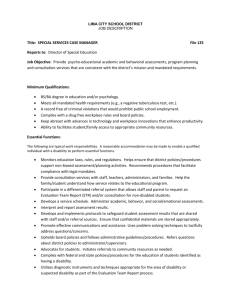

The computer says no – electronic incapacity reports LiMA is the computer software used by the DWP’s Medical Service to produce electronic medical reports for the personal capability assessment. David Simmons examines the system and some recent commissioners’ decisions which have considered its impact. Background The computer says no: electronic incapacity reports Background In 2002, SchlumbergerSema, the company contracted to provide the DWP’s Medical Service (MS), began trials of a new computer system called Lima (Logic Integrated Medical Assessment), designed to facilitate the provision of medical examinations and reports for the purposes of the personal capability assessment (PCA). Lima was rolled out on a national basis during 2003 and 2004. In 2004, SchlumbergerSema was taken over by Atos Origin, an international IT company which was recently awarded a new seven-year contract to continue to provide the MS. The contract includes a commitment to reduce the PCA processing times and improve the capabilities of Lima How does Lima work? Lima is part of the rapidly expanding computerised system of ‘evidence based medicine’ (EBM), which is being increasingly used in the NHS, private medicine and occupational health. EBM aims to provide health professionals with updated information on a wide range of medical conditions, to facilitate diagnosis and the production of electronic patient records and reports. Lima is specifically designed to guide doctors through the PCA examination and recording process, and to produce electronic versions of the medical report form IB85, which is used by DWP decision makers to determine whether a claimant satisfies the PCA. The software contains a store of standard terms and phrases most commonly needed by MS doctors when recording information on the IB85, based on updated information relating to the four main areas of incapacity – musculoskeletal, cardio-vascular, respiratory and mental health. It utilises a user-friendly, windows-based interface, which systematically takes doctors through the examination and recording process, enabling them to select and enter standard options (including the frequency of a symptom and severity of a condition) using a mouse. The system also allows for the standard options to be overridden and ‘free text’ to be entered directly. As well as prompting doctors to obtain and enter relevant information and complete all required sections of the report, one of the key features of Lima is that it provides ‘intelligent support’ by identifying ‘logical outcomes’ (hence the name Lima). It does this by automatically suggesting which PCA descriptors are satisfied based on the evidence recorded, and showing what evidence establishes its conclusions in relation to each descriptor. After entering the claimant’s choice of PCA descriptors from the information given on the IB50 questionnaire, the doctor records the claimant’s diagnosis; diagnosis history; medication (including side effects); treatment; social and occupational history; and activities carried out on a typical day. The examination findings are then entered (Lima identifies the examinations that must be completed from the IB50 information and opens a specifically designed screen relating to each examination, including a ‘mental state’ examination). The doctor then has to record ‘observed behaviour’ relating to relevant sub-groups of physical functionality (e.g. 'sitting, rising, bending'). A wide variety of standard terms and phrases relating to each section of the form are available for selection, as well as the facility to enter free text. At the end of the assessment, Lima automatically suggests which descriptors may apply, based on the information previously entered, and shows the evidence which supports each choice. If the doctor disagrees with the choices, s/he must override the system and justify doing so. The advantages of Lima Arguably, Lima has several potential advantages over the previous 'manual' reporting system, which was widely criticised for producing reports of highly variable quality. They include: immediate access to information based on up-to-date medical information and opinion; quicker and more efficient medical assessments; prompts for doctors to obtain and record all relevant information; greater consistency in examinations and reports; more legible reports; more logical and justifiable conclusions; easier monitoring of standards (in general and of individual doctors); easier and quicker electronic transmission of reports to decision-makers. Atos Origin are keen to stress that Lima supports 0- rather than replaces - doctors, who remain in control throughout the process and can override the automated features of the system at any stage. Problems with Lima Experience thus far (confirmed in recent case law – see below), suggests that currently, at least, problems with Lima are outweighing its potential advantages. Despite Atos’s assurances about doctors remaining in control, there is clearly a temptation for busy doctors to over-rely on Lima’s automated features, particularly when they are under pressure to reduce processing times. This can ‘dehumanise’ the assessment process and reduce the final report to a series of standard phrases (there has been anecdotal evidence of doctors hardly looking at claimants while they rush through Lima’s options, asking for ‘yes/no’ answers). Although Lima allows doctors to override the automated features, they are discouraged from doing so. The DWP’s Technical Manual on Lima for MS doctors (v2 12 October 2004) advises them to ‘use the supplied phrases whenever possible’ because Lima is unable to recognise free text when choosing appropriate descriptors. It also advises doctors to only override the automated choice of descriptors in exceptional cases. Two other features of Lima are of questionable validity. Firstly, most of the standard phrases relating to the ‘typical day’ are couched in terms of what the claimant can (as opposed to cannot) do. As the Technical Manual states, ‘Lima works best when it has positive information about the claimant’s abilities’. This is at odds with the law, which is about incapacity and inability to carry out prescribed functions. Secondly, in the words of the Manual, ‘Lima is programmed to give more weight to observed behaviour than to either the history or the examination’. The validity of this was recently called into question by a social security commissioner (see below). Commissioners’ decisions A number of commissioners’ decisions have considered Lima’s impact on the PCA, highlighting some of the above problems. CIB/476/2005 In CIB/476/2005 (Bulletin 186, p17), it emerged that the MS doctor had incorrectly input information about the length of time for which the claimant could sit and about her social life. The commissioner expressed concern that such mistakes will automatically carry forward to other sections of the report, unless corrected. He also pointed out that the system can produce repeated omissions as well as errors (in this case it failed to relate the claimant’s neck pain to her ability to sit) and questioned the validity of the phrase ‘Claimant states no other problems’ in the diagnosis box, as this was an ‘electronic default’, which may not have been based on what the claimant said, or the doctor’s assessment. The tribunal had erred in law by relying too uncritically on the electronic IB85. CIB/511/2005 In CIB/511/2005 (Bulletin 187, p17), the commissioner identified a number of apparent discrepancies and inconsistencies in the electronic IB85 and warned: ‘The use of this system, in which statements or phrases appear to be capable of being produced mechanically without necessarily representing actual wording chosen and typed in by the examining doctor, obviously carries an increased risk of accidental discrepancies or mistakes remaining undetected in the final product. Tribunals ought in my view to take particular care to satisfy themselves that reports presented to them in this form really do represent considered clinical findings and opinions by the individual doctor whose name they bear, based on what actually appeared on examination of the particular claimant’. CIB/664/2005 In CIB/664/2005 (Bulletin 188, p15), the commissioner agreed with the tribunal that the electronic IB85 relating to the claimant was unreliable. It contained nonsensical statements such as ‘Usually can do light gardening for 1 minutes’ and failed to carry forward relevant findings relating to the claimant’s mental state to the choice of the mental health descriptors. The commissioner also queried Lima’s emphasis on identifying the claimant’s abilities (as opposed to inabilities) and the additional weight given to ‘observed behaviour’ highlighted in the Technical Manual. He held that the Manual should be available to all tribunals, claimants and representatives to ensure ‘equality of arms’, pointing out that: ‘If the Manual’s advice is followed, the report seen by the claimant and tribunal is not the evidence considered by the doctor (which is itself a computer generated selection) but a selection from that evidence of the ‘most convincing’ case. A tribunal has to consider and weigh all the evidence. It may, therefore, need to re-examine all the evidence about each contested descriptor and make its own findings and conclusions, rather than rely on the evidence that the approved doctor considers ‘most convincing’.' CIB/1522/2005 In CIB/1522/2005 (Bulletin 187, p17), the tribunal was criticised for assuming that adopting the findings in the first part of the electronic IB85 entitled it to automatically agree with the choice of descriptors at end of the report, which may have been based on Lima’s automated procedures, or the doctor’s override. A tribunal must consider and make its own decisions on each descriptor in issue. Conclusion Lima has, in theory at least, the potential to produce more complete, accurate, consistent and legible IB85 reports. It can also, however, ‘dehumanise’ the medical assessment process and reduce the role of the MS doctor to selecting and entering standardised information, relying on the system to automatically reach conclusions, rather than using his or her clinical judgment to do so. Despite Atos Origin’s assurances that Lima is designed to support, and not replace, doctors, it is interesting to note that the company has announced its intention to pilot the use of ‘suitably trained’ healthcare professionals other than doctors (e.g. nurses) to carry out PCAs from early next year. Welfare Rights Bulletin 189 December 2005

![Alina%27s+biography[1].doc](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008053716_1-e26660debd094c135eb326538c217c07-300x300.png)