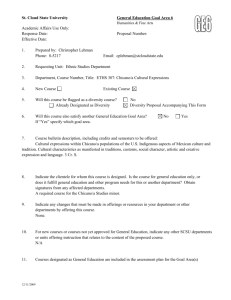

the-origins-of-chicano-literature2

advertisement

The Origins of Chicano Literature Early in 1967 Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales published his epic poem, "Yo soy Joaquín," better known as I Am Joaquín. By March the poem had already been adapted to film by the traveling activist troupe Teatro Campesino. The poem was mimeographed and widely circulated in order to be read during public demonstrations and organizing campaigns of what would come to be known as El Movimiento or the Chicano Movement. Beyond its immediate public activist function, however, I Am Joaquín also functioned as the inaugural work of what is now seen as the Chicano Literary Renaissance, lasting from the late '60s to the mid '70s. I Am Joaquín provided the groundwork, then, for all Chicano poetry to come. Yet what is perhaps more interesting is its role in serving as the founding literary work for all previous Chicano literature. Therefore, it can be argued that Chicano literature did not really exist until 1967, and after 1967, the whole history of Chicano literature from the 1600s to the 1960s suddenly, retroactively came into being. Moreover, prior to 1967 and the publication of I Am Joaquín, Chicanos did not exist, and yet after that moment we can see that they had been around for centuries. “Chicanos”: From Racist Term to Self Descriptor of Cultural Pride The term "Chicano," which many scholars suggest derives from a shortened version of the Indian pronunciation of "Mexicanos," was initially used as an insult, signifying a person of lower status and culture. This is in fact the way Mexican Americans were viewed by both Americans and Mexicans. Prior to the late '60s, even within the Mexican American community the term "Chicano" was reserved for recently-arrived immigrants. New arrivals from Mexico– often poor and more visibly "Other" than the more assimilated earlier Mexicans in America–threatened the status of those Mexican Americans who often fought hard to prove their American identity by distancing themselves from their Mexican and Indian roots. Later, however, the term was appropriated by Mexican-American activists during the 1960s in much the same way as the terms "Black" and then later "nigger" were by African Americans, as a way of transforming an insult into a signifier of ethnic strength and pride and as a refusal to assimilate into mainstream White culture. "Chicano" came to serve as a badge of militant identity within and against mainstream AngloAmerica. After 1967, then, the term "Chicano" served a consciously ideological function among young radicals as a designator of oppositional identity. The beauty of the poem I Am Joaquín lay in the way Gonzales wove together a wide variety of cultural and historical tropes into one emergent identity. Gonzales recounts the roots of Chicano identity in the long history of Mexican miscegenation through Spanish and Indian contact on up through the U. S. occupation and annexation of northern Mexico. The poem also displays the mytho-cultural icons of Chicano identity growing out of pre-Columbian Amerindian cultures. Then the poem surveys the history of Mexican American oppression and ends by imagining the future liberation of the Chicanos and their homeland. Through this poem, which was staged (and even filmed) as part of the public presentations of the Chicano civil rights movement, Mexican Americans were transformed into Chicanos. The Corrido Many scholars deem the poem a corrido, which has a long tradition in Mexico throughout all the different stages of its history. Although it had considerable resurgence during the Revolution, it continues to be a live musical form of expression in the present. Many folklorists trace its roots to the Medieval Andalusian verses and ballads brought by the Spanish. However, as the study of the native cultures of México sheds more light many scholars are linking the narrative style of the corridos to the Nahuatl and native epic poems (as seen in Anzaldúa’s The New Mestiza) Historical Origins of the Corrido Throughout its history Mexico has had many revolutions. The most famous perhaps is the Mexican Revolution from 1910-1920. The people of Mexico were getting tired of the dictator rule of President Porfino Diaz. People of all classes were fighting in the revolution. The middle and upper classes were dissatisfied with the President’s ways. The lower and working class people had many factors such as poor working conditions, inflation, inferior housing, low wages, and deficient social services. Within the classes everyone was fighting; men, women, and children all contributed to the fight for freedom from Diaz (Baxman 2). This revolution proved to be the rise and fall of many leaders. Everyone in Mexico was affected by The Mexican Revolution. Whether they were fighting for their freedom or wanted to escape the chaos, they were affected by the rise and fall of power. It also affected some people in the United States as Mexican immigrants came into the U.S. <http://www.mexconnect.com/MEX/austin/revolution.html, 1996.> Information about El Teatro Campesino El Teatro Campesino was the cultural wing of the United Farm Workers union, a popular theater that took its material directly from the lives of its audience in the bean fields of California's central valley. With a pointed political mission, the theater, and its driving force Luis Valdez, went from agitprop to Broadway. The foremost playwright of El Teatro Campesino, Luis Valdez, is regarded as the heart of this artistic, but political embodiment of Chicano culture. These performances addressed the Chicano experience in America in a context meaningful to all Americans. How the Plays Were Produced: Luis Valdez’s Vision In the mid '60s, flatbed trucks provided their first forum in the fields, adding a creative element to the struggles of farmworkers in Valdez's native Delano County. The immediacy of these actos, agitprop improvisations, communicated eloquently to many workers, who could neither read nor write, but recognized themselves and their values in what were essentially morality plays. El Teatro created site-specific installation in the truest sense of the format, transforming the fields into sociopolitical arenas, furthering the cause of the United Farm Workers union in their fight for human dignity. If Cesar Chavez was the upfront political figurehead of the farmworkers, then Luis Valdez provided its cultural wing with a flair and artistry that, in tandem, realized a solidarity unprecedented in relation to such emotional issues. El Teatro is popular theater with a deference to technical proficiency, to professional and performance excellence, all geared toward expression of social, political and cultural perceptions. It is a theater rooted in the American streets, early California history, Mayan/Aztec mythology and Mexican folklore and spiritualism. It cannot be ignored. Valdez, believes in a total theater—one where an elevation of sensation is achieved through a trinity of music, dance and drama to stimulate a "New American Audience." In the years since El Teatro's inception, the political erosion of many of the gains of the UFW has made a need for revitalization of the movement obvious. Though autonomous and independent of the union for a long time now, the unpretentious yet eclectic theater group still bases itself in its community, and preserves and rediscovers rites of identity of Mexico and the region.