And he answered, 'Here I am

advertisement

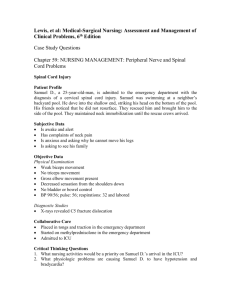

2 “And he answered, ‘Here I am.’”: An Educational Model for the Rav’s Halakhah of Suffering Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik’s Halakhah of Suffering can be brought to the classroom through a values-based analysis of the ‘hineni’ response in Tanakh. This paper argues for the importance of providing students with the tools to raise the moral, philosophical, theological and social questions such an analysis entails, and allowing students to grapple, indeed struggle, with them. The benefits of such an approach are considered and recommended. Medinah Korn has an M.A. in Tanakh from MaTaN, where she currently serves as the Head Librarian. 3 Introduction In the many works that comprise the literary oeuvre of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, very few relate directly to a concrete vision of Jewish education. If we would still attempt to construct a sort of Soloveitchikian educational theory, however, it might seem most logical to begin with those few.1 And yet all of his other published lectures and writings contain his theological, philosophical, religious and social views, “as if these had no clear bearing on the field of education.”2 To obtain a broader perspective of our sought educational theory, it is therefore necessary to extrapolate pedagogical messages from within these other philosophical works. The dilemma of the existence of evil in the world, of zaddik ve-ra lo, the righteous man who suffers, is a topic that teachers tend to shy away from addressing deeply. By deeply I mean shunning the simple one-liners that silent the inquisitive student, and courageously attacking the problem at its core, at its very essence, raising the many moral, philosophical, theological and social questions and allowing students to grapple, indeed struggle, with them. While this task did not daunt the Rav on a personal level – various conceptions of dealing with human suffering reverberate throughout much of his writing – he did view the experiential side of teaching as one of the educator’s most intimidating and, at the same time, most crucial tasks. The Rav relates this feeling with regard to teaching about his experience of the Yamim Noraim, the Days of Awe, when he was young: From an intellectual standpoint there is much I can transmit to my pupils from what I absorbed from my forefathers and from my mentors about the significance of the day, about the sanctity of the Days of Awe. What I cannot pass on are the experiences that I myself underwent on those days. I cannot give rise in them to … the emotion I felt when I heard my grandfather, Rabbi Haim, tremulously breathe the words which describe the service in the Temple on the Day of Atonement.... One could well-nigh see that at that moment Rabbi Haim dwelt in another world …. This is a feeling that a Jew must personally experience; it does not lend itself to transmission via theological 1 See, for example, many of the insights cited in Aaron Rakeffet-Rothkoff, The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. Edited by Joseph Epstein. 2 vols. (New Jersey: Ktav Publishing House, 1999). 2 Oded Schreimer, “Toward Understanding Buber’s I-Thou and I-It Dichotomy in the Context of Education,” Journal of Jewish Education 2 (1984): 212. 4 tractates and essays, homilies and sermons. It is a feeling – and it must be experienced! … I can give instruction on various subjects – but not on this.3 While the trouble that the Rav describes here relates to encouraging positive, uplifting emotions, the same, perhaps even greater, difficulty can be imagined when trying to relate methods of dealing with tragedy in a classroom. Reading the Rav’s approach to suffering may at first make us feel the challenge even more intensely. Let us first look at the ideas presented in some of his writings and then consider the pedagogical test we face in bringing these ideas to the classroom. The Rav’s Halakhah of Suffering For our purposes we will analyze two passages, one from Kol Dodi Dofek4 and one from the more recent publication, Out of the Whirlwind.5 Two messages of suffering are presented in these essays. In Kol Dodi Dofek, the Rav focuses more on suffering as a means toward self-improvement; in Out of The Whirlwind, suffering is presented as an end unto itself, an inherently valuable and indeed essential experience. These messages overlap in each of the essays as the Rav describes the dialectic of the existence of man. Man “oscillates … like a pendulum”6 between two existences, of fate and destiny; of cosmic and covenantal; of an object-like passive existence and an active, creative one; of orderliness and chaos; of physical pain and mental anguish. In the fateful, cosmic, object-like existence, man is not even so much as an individual. He is merely a pawn on a gameboard of being, moved at the whim of a Player. He is the passive man of Creation, a slave in bondage, uninvolved, powerless7. He lives a “tohu va-vohu [nothing] existence,” anonymous in history, having left no indelible mark, and ignorant of destiny.8 3 Joseph B. Soloveitchik, On Repentance, ed. Pinchas Peli (Jerusalem: Orot Press, 1981), 149-50. See also Moshe Simkovich, “Teaching Rabbi Soloveitchik’s Thought in the High School Classroom,” in Wisdom From All My Teachers: Challenges and Initiatives in Contemporary Torah Education, eds. Jeffrey Saks and Susan Handelman (Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 2003), 341-359. 4 Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “Kol Dodi Dofek: It is the Voice of My Beloved That Knocketh,” Theological and Halakhic Reflections on the Holocaust, ed. Bernard Rosenberg (New Jersey: Ktav Publishing House, 1992): 51-117. Henceforth KDD. 5 Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “Out of the Whirlwind,” in Out of the Whirlwind: Essays on Mourning, Suffering and the Human Condition, eds. David Shatz, Joel B. Wolowelsky and Reuven Zeigler (New Jersey: Ktav Publishing House, 2003): 116-150. Henceforth OOW. 6 OOW, 148. 7 B. David Schreiber, Sefer Noraot ha-Rav, Vol. 7, Shene derashot al inyane yamim tovim u-megillat ester, Me-et ha-Gerid ha-Levi Solovaits’ik (Forthcoming): 34-5, for one explanation of the Rav of three possible relationships between man and God. 8 Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “Redemption, Prayer Talmud Torah,” Tradition 17: 2 (1978): 61-62 5 The Rav maintains that it is “man’s task in this world to transform fate into destiny,” to become an acting, reacting being, to become an I-individual. Why? It is only the man of destiny who can be realistic in “confront[ing] the environment into which he was thrown … [who can] live like a subject, like a creator, an innovator, who can impress his own seal upon his life”9 and upon history, for generations to come. And it is only when man lives such an existence that he can encounter God. Indeed, it is in the transition, the passage from an existence of fate to an existence of destiny that this confrontation occurs. How so? The catharsis of becoming a man of destiny, the Rav describes, occurs through suffering. Anyone who is prepared to declare that evil exists and confront it head-on is prepared to suffer. That same person is not interested in the lama, the “causa and rationale” of suffering, but rather the madua,10 the “norm, the kerygma, the message.”11 Man leading an active existence “asks neither about the cause of evil nor about its purpose, but rather how it might be mended and elevated.”12 While contemplating how to act in the face of evil and catastrophe, the man of destiny also asks, “why me?” He is surprised that he has been singled out for a tragic experience, and is lonely in his quest for meaning. So too a person experiencing Divine revelation: a person to whom God appears is also traumatized by having been chosen. And since, as the Rav explains, it is only the man of destiny, not the man of fate, who can experience sorrow (by contrast to pain), then in a sense one who suffers either has experienced of is in the process of experiencing some form of Divine revelation. The man of destiny is commensurate with covenantal man: he has encountered God and bound himself to a covenantal relationship through his agonizing experience. The sufferer, as the recipient of Divine revelation, in realizing that he has been singled out, must respond “Hineni; here I am,” prepared to allow the “catastrophic experience [to] be assign[ed] … a position within [one’s] inner world.” Revelation, through the experience of suffering, one might say, is what allows man to reach the heights of his “transcendental-covenantal nature.”13 Man cannot make that transition without the willing consent of Hineni. 9 KDD, 54. See note 15. 11 OOW, 128. 12 KDD, 56. 13 OOW, pp. 132, 148, 140, 119. 10 6 In responding Hineni to his call to action he has also demonstrated a sensitive “time-consciousness.”14 He knows that if he does not respond to the Divine call at that very moment, he will miss it. The Educational Challenge Why are we educators afraid of incorporating these ideas into our course material? What is the challenge we face in presenting an intellectual analysis of an experiential dilemma? First, as we have said, experience cannot necessarily be described in words. Can one allude to it? Perhaps. If the student has undergone a similar experience, our story will speak to him or her intimately. If the teacher faces a group who has felt emotions similar to the nihility and loneliness that the Rav describes, he or she can proceed smoothly to discuss appropriate responses. One educator has described how Rabbi Norman Lamm utilized such a situation: On the morning of September 11, 2001, I found myself on the uptown campus of Yeshiva University. As it was for the entire country and for much of the world, initial reactions to the attacks on the World Trade Center were little more than shock and disbelief. Particularly for those located so close to the disaster, it was difficult to absorb what transpired that morning. In response to the events of the morning, student leaders at Yeshiva quickly organized an outdoor Mincha and Tehillim rally. The main speaker at this rally was Rabbi Norman Lamm … There is one thought that he stressed that I have not forgotten. David Hamelech exclaims in Tehillim "keili keili lama azavtani?". [“My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”] Rabbi Shimshon Rephael Hirsh explains that in Hebrew, one can ask "why" with the use of the word madua or of the word lama. The word madua means why in its purest sense, wanting to know the reason behind something, what caused it to happen. On the other hand, lama comes from the words "le ma," literally "to what," trying to figure out not what caused something to happen, but rather what is the purpose that is meant to come out of the occurrence. And so when David Hamelech feels deserted by Hashem, he does not ask madua. It is not his place to question the causes of the actions of Hashem. Rather he asks lama. What is meant to come out of the actions of Hashem? What responsibilities do they place upon me? This must be our response to tragedy as well, explained Rabbi Lamm to the hundreds of students and faculty assembled on the lawn outside of Rubin Hall. It is futile to try to understand the reasons or causes for such a horrible occurrence. What we can do, however, is to try our best to figure out the ends to which events such as the attacks of September 11th are meant to bring about in our lives. In the illustration of the Rav, we must view the 14 OOW, 123. 7 whirlwind of that horrible day as a way that Hashem is calling out to us. We must be ready to respond, to listen to His voice, and to take action when needed.15 Rabbi Lamm’s words resonated perfectly for this audience, having just witnessed such a horrifying catastrophe. Would these words have the same impact on one who was not in Manhattan that morning? Several educators have established, however, the need for developing discussion-based lessons to both connect with the witnesses and bring the messages to those who have not experienced existential trauma. After all, if we have claimed that one cannot encounter the Divine without experiencing some form of suffering, do we not owe it to our students to give them the tools to recognize the call? Professor Isadore Twersky, z”l, has delineated that when we speak of the “educated person,” it is clear that we are discussing not only the sum total of a person’s knowledge, but also, and perhaps most significantly, a system of attitudes. We attempt to establish not what a person should know, but what a person is, his nature, spiritual character, modes of behavior, spiritual and moral aspirations. Every educational philosopher admits that education intends to shape a certain kind of personality in accordance with values and beliefs. The educated person reflects, as in a mirror, the ideal person, who represents the embodiment and fruition of these values.16 Our goal is not just to educate toward knowledgeable students, but toward spiritually rich students. The risks we take in leaving emotions off our educational agenda should weigh more heavily on our conscience then creating an opportunity to present them. Susan Handelman has described the initial frustration of a student of hers in a Bible course she taught in a large State university, at thinking she needed to repress getting emotionally wrapped up in the text. Why not get emotionally involved …. Why am I discouraged [from trying] to experience books …. I have been trying to read the Bible critically. It’s difficult because its language demands 15 Yaakov Mintz, ATUDA email, September 19, 2004. Isadore Twersky, “What Must a Jew Study – and Why?” in Visions of Jewish Education, eds. Seymour Fox, Israel Scheffler and Daniel Marom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003): 50. 16 8 both an intelligent and passionate reading. Isn’t reading supposed to change us and the world in some way?17 By contrast, the educator who does encourage the pedagogy of emotion in his or her classroom can savor the initiative, creativity, energy, and dedication that are released when students know they can express themselves freely … [This burst] shows, by contrast, how accustomed they are to holding back, playing it safe, avoiding real engagement, or just going through the motions.18 This educational theorist was speaking about the students “playing it safe,” but her ideas here certainly apply to the teachers who avoid certain topics because they are more difficult or problematic to tackle. This challenge is one that Rabbi Twersky calls us to with regard to shaping an educated person in Torah. Yael Unterman has also called for creating new goals for the Yeshivah in nurturing spiritual completeness in helping students develop a relationship with God. She challenges us to “strive to distinguish what “resonates” in them [the students] in whatever they learn from us, by asking them, ‘How is what we just learned relevant to you?’”19 Would we not teach the commandments of loving and fearing God just because they do “not concern intellectual or rational understanding … [just because they have] different meanings for different people, and therefore are difficult to prove or define [?]”20 We would not dare. Maimonides, in his explanation of these commandments, left us with a pedagogical legacy of an ability to bring those emotional, abstract concepts somewhat closer to the human logical sphere. We can attempt to do the same in suggesting methods for dealing with the messages behind Susan Handelman, “We Cleverly Avoided Talking About God: Personal and Pedagogical Reflections on Academia and Spirituality,” Courtyard: A Journal of Research and Thought in Jewish Education 1 (1999): 105. 17 Jane Thompkins, A Life in School: What the Teacher Learned, in Susan Handelman, “Cleverly,” 109. 19 Yael Unterman, “If You Seek Him With All Your Heart: Nurturing Total Individual Growth in Yeshivah,” Wisdom From All My Teachers, 162. This article focuses specifically on the post-high school one-year programs in Israel, but many of her arguments could certainly be applicable in high school and elsewhere as well. For more information on dealing with emotions in the classroom with younger children, and specific lessons as such, see Larry Scheindlin, “Emotions in Jewish Education,” Courtyard: A Journal of Research and Thought in Jewish Education 1 (1999): 121-141. 20 Chaim Brovender, “Towards Ahavat Hashem: Art and the Religious Experience,” in Wisdom From All My Teachers, 55. See also his analysis of Maimonides’ discussion of the commandments to love and fear God in the same article, pp. 54-61. 18 9 the emotions of suffering. I would like to suggest that teachers begin to open the discussion by looking at the broader Biblical context of the Hineni response that the Rav deems necessary as a reaction to suffering. Highlighting the aspects of the Biblical texts that allude to the depth of experience that the Rav has described can give students a reference point and a rudimentary vocabulary for conceptual analysis. Such an approach, rather than using blatant disaster as the starting point, starts with the Divine encounter and the struggle that such a confrontation entails. This path is one that suggests a “trace, that hints, points, invites, but does not compel” 21 students to encounter these ideas. It allows them to cover ground at their own pace by starting with the scenes of Abraham’s, Samuel’s and Moses’ encounters with the Divine, that may not seem so much like suffering to them at first glance. The Hineni Response and Its Pedagogical Implications The word hineni, literally translated ‘here I am,’ appears in several scenes in Tanakh as a model response to God’s calling. It points not only to an open readiness to listen to and recognize God, but also indicates a willingness to assume responsibility for God’s message, to act in a leadership role that demands acknowledging and responding to suffering. The intensity of the suffering of Abraham, Samuel and Moses evident in each one’s ‘hineni process’ needs to be evaluated one by one in context, and in juxtaposition to the others. Abraham In Abraham’s case, his encounter with the Divine in the Akeidah story is not the first time he has spoken with God. Indeed, as the Rav points out, the covenant that was established between God and Abraham and his descendants came about through suffering. Genesis 15 is a “weird scene, full of undefined dread and grisly uneasiness.”22 ) (יג:ימה חֲ ֵּׁשכָה גְ ֹדלָה נֹ פֶּׁ לֶּׁת עָ לָיו ָ ֵַּאב ָרם וְ ִהנֵּה א ְ (יב) וַ י ְִהי הַ ֶּׁשמֶּׁ ׁש לָבוֹא וְ ַת ְרדֵּ מָ ה נָפְ לָה עַ ל ַארבַ ע מֵּ אוֹת ְ וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר לְ ַאבְ ָרם ָידֹעַ ֵּת ַדע כִ י גֵּר י ְִהיֶּׁה ז ְַרעֲ ָך בְ אֶּׁ ֶּׁרץ ֹלא לָהֶּׁ ם וַ עֲ בָ דּום וְ ִענּו אֹ ָתם : (יד) וְ גַם אֶּׁ ת הַ ּגוֹי אֲ ֶּׁׁשר יַעֲ בֹדּו ָדן ָאנֹ כִ י וְ ַאחֲ ֵּרי כֵּן י ְֵּצאּו ִב ְרכֻׁש ּגָדוֹל:ָׁשנָה 21 22 Susan Handelman, “Cleverly,” 108. OOW, 119. 10 As the sun was about to set, a deep sleep fell upon Abram, and a great dark dread descended upon him. And He said to Abram, “Know well that your offspring shall be strangers in a land not theirs, and they shall be enslaved and oppressed four hundred years; but I will execute judgment on the nation they shall serve, and in the end they shall go free with great wealth….”23 By Genesis 22, God has already seen quite a lot of willing action on Abraham’s part. And yet He tests him again. The Hineni response in this chapter of Genesis is a catalyst theme; it is the actions of Abraham, both in response to God and to Isaac, that prove the strength of his Hineni. In answering Hineni to God’s call, Abraham shows an interest in a relationship with the Divine, an interest in transformation from cosmic man to covenantal man, or, in the terms Rav Soloveitchik uses in Kol Dodi Dofek, from a man of fate to a man of destiny.24 Though Abraham, as a father, must be experiencing inner turmoil at the thought of losing his only son, of losing everything that God promised him in previous encounters, the reader sees only pure “courage and discipline … untainted by the slightest hint of partiality or self-indulgence”25 on his part. Note also the nuance in the way God addresses Abraham at the very last moment before he sacrifices Isaac: :ַאב ָרהָ ם וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר ִהנֵּנִ י ְ (יא) וַ י ְִק ָרא אֵּ לָיו מַ לְ אַ ְך ה' ִמן הַ ָשמַ יִם ַויֹאמֶּׁ ר ַאבְ ָרהָ ם Then an angel of the Lord called to him from heaven: “Abraham! Abraham!” And he answered, “Here I am.”26 The word va-yikra has not been used to initiate any previous dialogue with Abraham. Further, God calls Abraham’s name twice, urgently, emphatically. When the hineni response is coupled with this manner of speaking, the Revelation-level, covenantallevel relationship is produced. The pace of the chapter decelerates: Abraham has 23 Genesis 15:12-3. All Biblical translations follow Tanakh: A New Translation of The Holy Scriptures According to the Traditional Hebrew Text (Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1985). 24 It would be interesting to compare these distinctions of Rav Soloveitchik with similar ones of Franz Rosenzweig in his Star of Redemption. Rosenzweig illustrates a view of reality showing how God, Man and the World are related through the processes of Creation, Revelation and Redemption. The Revelation experience, as Rosenzweig describes it, is the coming out of self of both God and man. God searches for new self-definition as He calls upon man to recognize Him. Man must acknowledge God fully in return so that he can become an I, an independent being for whom God is the Thou. It is the Hineni response that can allow for a Revelation-level relationship to be produced. 25 KDD, 64. 26 Genesis 22:11. 11 passed the test. It is Abraham’s story that is chosen for the Torah reading on the second day of Rosh ha-Shanah as the paradigm hineni response over other possibilities in Tanakh. Abraham has suffered, and questioned, and through that process has concretized his relationship with God through action. Samuel We find similar language in Samuel’s hineni story. The dialogue that contains the hineni response in Samuel chapter 3 is the very start of the contact between God and Samuel, the beginning of God’s search for Samuel to recognize Him. And a search it is indeed, as Samuel did not yet know God, “terem yada,”27 and mistakenly assumes that Eli the priest is calling. Even though Samuel does not respond directly to God the first few times, he demonstrates a zealousness to recognize a Thou when he responds hineni and hurries to Eli.28 When God finally calls Samuel’s name twice in a row, using the word va-yikra to describe His tone of voice as it were, Samuel can respond appropriately: :(י) ַו ָיבֹא ה' וַ י ְִתיַצַ ב ַוי ְִק ָרא כְ פַ עַ ם בְ פַ עַ ם ְׁשמּואֵּ ל ְׁשמּואֵּ ל וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר ְׁשמּואֵּ ל ַדבֵּ ר כִ י ׁשֹמֵּ עַ עַ בְ דֶּׁ ָך The Lord came, and stood there, and He called as before: “Samuel! Samuel!” And Samuel answered, “Speak, for Your servant is listening.”29 Though it might seem that Samuel is just following orders from Eli to respond as an obedient servant, it is obvious that Samuel is prepared to connect with God on a hineni level from his previous hineni answers. God, as a new Thou for Samuel, acknowledges the newly emerged I in Samuel: (כ) וַ י ֵַּדע כָל י ְִש ָראֵּ ל ִמ ָדן וְ עַ ד:ָארצָ ה ְ (יט) וַ יִגְ ַדל ְׁשמּואֵּ ל ַוה' הָ יָה עִ ּמ ֹו וְ ֹלא ִהפִ יל ִמכָל ְדבָ ָריו :'בְ אֵּ ר ָׁשבַ ע כִ י נֶּׁאֱ מָ ן ְׁשמּואֵּ ל לְ נָבִ יא ַלה Samuel grew up and the Lord was with him: He did not leave any of Samuel’s predictions unfulfilled. All Israel, from Dan to Beersheba, knew that Samuel was trustworthy as a prophet of the Lord.30 27 I Samuel 3:7. Note the different verbs used to describe Samuel’s actions here, and their indication of Samuel’s zealousness. For a detailed analysis, see Shimon Bar-Efrat, I Samuel: Introduction and Commentary, (Jerusalem: The Magnes Press, 2002): 77-85. 29 I Samuel 3:10. 30 I Samuel 3:19-20. 28 12 The fact that Samuel was shaken up by his dialogue with God on that night is manifest in the fact that he does not run to tell Eli what has happened. The boy Samuel returns to the comfort of his covers and lies there, perhaps trembling in the “shock [of] being confronted with infinity,”31 until the morning. At dawn he clings to his routine; maybe, he thinks to himself, he does not have to respond after all. He hesitates. “U-Shmuel yare,”32 he was afraid – of what lay in store both for him and for his beloved mentor Eli. What could a child understand of leadership? How can he now rise above Eli and predict his downfall? He is tormented, utterly confused by a foreign encounter in the mysterious darkness of the night. He feels he cannot share this experience: he is lonely. Ultimately he moves beyond this emotional turmoil to transform himself into a leader. This process takes time, though, and is not without its roadblocks. Samuel does not approach Eli himself; Eli begs for an explanation from him. Samuel becomes a leader who will respond when asked or when forced perhaps, but will not completely initiate action. Later, Samuel follows God’s command to anoint Saul, but not without taking the nation’s request personally; an undercurrent of tension exists between Saul and Samuel as they try to share the leadership role. Samuel is not completely confident in his ability as a leader, as is evident by his request from the nation to testify before God that he has done them no wrong.33 God sought a leader in Samuel because he demonstrated a passionate service to Eli, and by responding hineni to the Unknown, a willingness to serve an Authority faithfully. Moses Rav Soloveitchik uses Moses as his ideal example of one who experiences the “trauma … caused by the surprise of being singled out.” God tries to establish the Revelation-level relationship in His first contact with Moses: :ֹלהים ִמתוְֹך הַ ְסנֶּׁה ַויֹאמֶּׁ ר מֹ ֶּׁׁשה מֹ ֶּׁׁשה וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר ִהנֵּנִ י ִ ֱ(ד) וַ י ְַרא ה' כִ י סָ ר לִ ְראוֹת וַ י ְִק ָרא אֵּ לָיו א When the Lord saw that he had turned aside to look, God called to him out of the bush: “Moses! Moses!” He answered, “Here I am.” 31 OOW, 121. I Samuel 3:15. 33 See I Samuel 12: 1-5. Note that a comparison is drawn between Moses and Samuel as leaders by the assignment of I Samuel 14-5 as the haftarah for Parashat Korah, which includes Numbers 16. 32 13 Again we see the double name-calling, the word va-yikra, and the ready and willing hineni response. We know however, from the Samuel analysis, that a hineni response does not necessarily indicate an Abraham-type immediate action. And Moses’ indeed argues with God: ֹלהים ִמי ָאנֹ כִ י כִ י אֵּ לְֵּך אֶּׁ ל פַ ְרעֹה וְ כִ י או ִֹציא אֶּׁ ת ְבנֵּי י ְִש ָראֵּ ל ִ ֱ וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר מֹ ֶּׁׁשה אֶּׁ ל הָ א.1 :ִמ ִּמ ְצ ָריִם But Moses said to God, “Who am I that I should go to Pharaoh and free the Israelites from Egypt?” ָאמ ְר ִתי לָהֶּׁ ם אֱ ֹלהֵּ י ַ ְֹלהים ִהנֵּה ָאנֹ כִ י בָ א אֶּׁ ל ְבנֵּי י ְִש ָראֵּ ל ו ִ ֱ וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר מֹ ֶּׁׁשה אֶּׁ ל הָ א.2 :ָאמרּו לִ י מַ ה ְשמ ֹו מָ ה אֹ ַמר אֲ לֵּהֶּׁ ם ְ ְאֲ בו ֵֹּתיכֶּׁם ְׁשלָחַ נִ י אֲ לֵּיכֶּׁם ו Moses said to God, “When I come to the Israelites and say to them ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me ‘What is His name?’ what shall I say to them?” :’ֹאמרּו ֹלא נִ ְרָאה אֵּ לֶּׁיָך ה ְ וַ יַעַ ן מֹ ֶּׁׁשה וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר וְ הֵּ ן ֹלא יַאֲ ִמינּו לִ י וְ ֹלא י ְִׁש ְמעּו בְ קֹ לִ י כִ י י.3 But Moses spoke up and said, “What if they do not believe me and do not listen to me, but say: The Lord did not appear to you?” וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר מֹ ֶּׁׁשה אֶּׁ ל ה’ בִ י אֲ ֹדנָי ֹלא ִאיׁש ְדבָ ִרים ָאנֹ כִ י ּגַם ִמ ְתמוֹל ּגַם ִמ ִשלְ ׁשֹם ּגַם מֵּ ָאז.4 :ַדבֶּׁ ְרָך אֶּׁ ל עַ בְ דֶּׁ ָך כִ י כְ בַ ד פֶּׁ ה ּוכְ בַ ד לָׁשוֹן ָאנֹ כִ י But Moses said to the Lord, “Please, O Lord, I have never been a man of words, either in times past or now that You have spoken to Your servant; I am slow of speech and slow of tongue.” : וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר בִ י אֲ ֹדנָי ְׁשלַח נָא בְ יַד ִת ְׁשלָח.5 But he said, “Please, O Lord, make someone else Your agent.” 34 In the first argument, Moses is traumatized by the “Why me?”, “Mi anokhi?”, as the Rav delineates: The individual who was elected by the Almighty out of the crowd with which he identified until the last instant suddenly finds himself different from others. In his dialogue with God he is lonely, since no one joined him in this paradoxical adventure, no one shares the burden which was foisted upon his shoulders …. The indescribable content of the great message ... can never be told and explained. The elected remains a solitary figure...35 34 35 Exodus 3:11, 3:13, 4:1, 4:10, 4:13. OOW, 132-3. 14 Moses’ problem is his own self-definition as it relates to God. He does not want the task, because, as he claims in his fourth appeal, “lo ish devarim anokhi,” I am not a man of words. Why should the anokhi be me?36 God remains patient after Moses’ weak argument that the people will ask for His name; the Thou continues to search for the I as He outlines the detailed direction Moses will receive. God is even patient with Moses as he claims that perhaps the nation will not believe him, as if to say it is not he, but rather the nation, who cannot – or will not – accept the I responsibility. But God will not take no for an answer; when Moses begs for a replacement, God responds indignantly. The scene which began as puzzling has turned dreadful. Moses is not given another chance to speak for himself, and the I responsibility is almost forced upon him. Perhaps the hineni response already committed Moses. Moses said hineni showing an inner basis for the I that just needed a little encouragement to emerge. As God saw potential in Samuel that made it worthwhile to call him several times over until he answered, He “fights” to bring out the I that He sees in Moses. Moses struggles with the I responsibility throughout his career, continuing to doubt that he is appropriate for his position. The most powerful example of his inner struggle is in his complaint after the nation sins at kivrot ha-ta’avah. The structure of the complaint centers on his personal feeling of anokhi, of the burden of the responsibility he did not originally seek: (יא) וַ יֹאמֶּׁ ר מֹ ֶּׁׁשה אֶּׁ ל ה’ לָמָ ה הֲ ֵּרע ָֹת לְ עַ בְ דֶּׁ ָך וְ לָּמָ ה ֹלא מָ צָ ִתי חֵּ ן בְ עֵּ ינֶּׁיָך :לָשּום אֶּׁ ת מַ ָשא כָל הָ עָ ם הַ זֶּׁה עָ לָי יתי אֵּ ת כָל הָ עָ ם הַ זֶּׁה ִ (יב) הֶּׁ ָאנֹ כִ י הָ ִר ִאם ָאנֹ כִ י יְלִ ְד ִתיהּו כִ י תֹאמַ ר אֵּ לַי :ָשאֵּ הּו בְ חֵּ יקֶּׁ ָך כַאֲ ֶּׁׁשר י ִָשא הָ אֹ מֵּ ן אֶּׁ ת הַ ֹינֵּק עַ ל הָ אֲ ָדמָ ה אֲ ֶּׁׁשר נִ ְׁשבַ ְע ָת לַאֲ ב ָֹתיו (יג) מֵּ ַאיִן לִ י בָ ָשר ל ֵָּתת לְ כָל הָ עָ ם הַ זֶּׁה כִ י יִבְ כּו עָ לַי :לֵּאמֹ ר ְתנָה לָנּו בָ ָשר וְ נֹ א ֵּכלָה ָשאת אֶּׁ ת כָל הָ עָ ם הַ זֶּׁה ֵּ (יד) ֹלא אּוכַל ָאנֹ כִ י לְ בַ ִדי ל :כִ י כָבֵּ ד ִמּמֶּׁ נִ י And Moses said to the Lord, “Why have You dealt ill with Your servant, and why have I not enjoyed Your favor, that You have laid the burden of all this people upon me? Did I conceive all this people, did I bear them, that You 36 This is almost as if to say how can I be anokhi if You are the Anokhi of the Decalogue. How can I be a leader if You are the leader? 15 should say to me, ‘Carry them in your bosom as a nurse carries an infant,’ to the land that You have promised on oath to their fathers? Where am I to get meat to give to all this people, when they whine before me and say, ‘Give us meat to eat!’ I cannot carry all this people by myself, for it is too much for me.37 Moses approaches the leadership role as a masa, a burden, which is all upon him, alai, one that he bears alone, levadi. The metaphor of pregnancy and birth is strong in this passage; Moses examines whether the responsibility should be his, given that the people are God’s children and not his own. It is particularly interesting for our purposes that despite the trouble Moses displays with the I-responsibility, he achieves the most intimate relationship with God: “face to face, as one man speaks to another,”38 a level that no one else reaches. Moses suffers the most, and achieves the greatest result, the closest relationship with the Holy One. Moses did not “flinch from confronting evil face to face”39 – he addressed problems where he saw them and tried to solve them to the best of his ability. It makes sense that Moses functions as the Rav’s paradigm “why me?” because, for the Rav, he is also the leader who established profound distress over the prospering of the wicked, by asking God, in that face to face encounter, the “question of questions, [that] prophets and sages, through all the generations [up to the present] have continued to grapple with.”40 If anyone would be enlightened about the answer to this query, it would have been him. And while he experienced torment and anguish, he did not stop from demonstrating that he knew the response to suffering: liberation. Moses is the messenger-deliverer of the Hebrew slaves, living in a world of fate, headed toward a world of destiny.41 Hineni and Educational Goals In presenting these texts to the classroom, teachers should use the comparison as a means of “modeling a moral quality or anchoring a philosophical position.”42 37 Numbers 11:11-14, emphasis added. Exodus 33:11. 39 KDD, 55. 40 KDD, 51. See also KDD, 105, n.1 about the dispute in Berakhot 7a between R. Meir and R. Yose over whether Moses received an answer to his query. 41 Here the Rav’s analysis of the Zohar’s description of the stages of redemption from Egypt is most poignant. See Soloveitchik, “Redemption, Prayer, Talmud Torah,” 66. 38 42 Twersky, “What Must a Jew Study – and Why?” 71. 16 This requires a value-oriented and not a pure factual presentation. While teaching these texts we must ask the students questions about what they think of the characters themselves. Encourage them to feel the characters emotions, good and bad, and ask themselves, “How does this relate to me? How can I apply this to my life?” Each classroom setting needs to create a vocabulary that is appropriate to the level of its subjects. A teacher might ask students to imagine a scenario where they have felt “shaken” by an interpersonal experience.43 effective in producing a desirable result? Do they think this experience was What did this frightening experience produce that a more peaceful, orderly one may not have? Evil can be used as a code word for any difficulty they have encountered merely in order to help them grasp the concepts on their own terms first. “[Blank] exists and I will neither deny it nor camouflage it … I am concerned about [blank] from a halakhic standpoint, like a person who wishes to know the deed which he shall do.”44 A specific seminar on these matters might be most effective at the beginning or end of a school year, periods that naturally lend themselves to reflection and introspection. Students may have set goals for the year that they were able to accomplish only under the pressure of the deadlines of the last week of school. Do they understand the pressure of time awareness that forces them into an acting, hineni, consciousness? One educator has pointed out that “end of a cycle” experiences, while not always as painful as the suffering that the Rav describes, can function in a similar manner. While we are caught up in the middle of a cycle we engage in normal activities, hardly noticing that time is passing. But at the end of a week/year we become aware of the fact that time is passing, and indeed has passed. We experience a sense of loss, and then we are compelled towards action, out of a desire to make the most of time.45 Another important point to stress is the positive expressions that can come out of the suffering.46 Can students think of a positive outcome from any misfortune they have known? 43 My thanks to Rabbi Moshe Simkovich for pointing out this pedagogical direction out to me. KDD, 55. 45 Shoshana Lockshin, ATUDA email, September 19, 2004. 46 Another text relevant toward that part of the discussion is certainly the Book of Ruth. Avivah Zornberg presents an analysis along these lines in her chapter, “The Concealed Alternative,” in Reading Ruth: Contemporary Jewish Women Reclaim a Sacred Story (New York, Ballantine Books, 1994): 65-81. 44 17 At this point in the discussion, I believe it is relevant to bring personal stories that may speak to the students more intimately now that they have the analytical vocabulary. One personal story rings loud in my ears. It is the story of two individuals who came together to donate organs on another’s behalf: certainly a sacrificial, proactive undertaking that requires an acute time-awareness. The following was written by one of the donors just 7 weeks after the death of the recipient who did not survive the surgery. I am still trying to make sense of it all.... Even though it failed, this endeavor was a good thing. I felt, in the time leading up to the operation, as good people came together for this, as prayers were being offered not only in Newton, in Columbus, in New York, all over the country and all over the world, that G-d was watching, that He blessed the endeavor, that He saw this a good thing, but as always, did not guarantee the outcome …. After it was over we all tried to find meaning – it was right in front of us. All of us who participated in this endeavor, near and far, were transformed by it. The outpouring of help and real empathy beforehand and afterward were extraordinary …. For all adults and children who took part, helped or simply observed, they emerged as better people, they had a benchmark event by which they could measure chesed. I am sure that years down the line, in ways we know nothing about, in ways we cannot predict, many acts of kindness will be performed by the participants and the children of the participants of the event …. These acts of kindness will be the echo of what happened that day …. In a curious way, this was Rosalie’s last gift to all of us. By being who she was, she called us to this task. I know that I, and I suspect that Sabina, did not really think of our doing anything really special. It was Rosalie who called and we just had to answer. In the end … this task … made all of us better for having tried. In the final analysis we became better people because of what was done for her. She enriched our lives and left a legacy of chesed that will be manifest for many years to come.47 Judaism is a pro-active religion. “Our religious consciousness”, even in the face of death, the Rav has said, “is life-oriented, and in-life rooted.”48 When faced with or given the choice between life and death, blessing and curse, u-vaharta ba-hayim – choose life, choose action. Bring the students to understand the possibility of goodness coming out of sorrow, learning their lesson not by asking for compensation for the suffering – not asking lama – asking how we must move forward in the face of adversity. Teachers and students should recall together, as a learning process, what 47 Personal email from my uncle, Dr. Sheldon Landesman, October, 2000, who donated a piece of his liver to try to save the life of his sister, my mother, Rosalie Katchen, a”h. Also in honor of family friend Sabina Feczko, who donated her kidney. 48 Joseph B. Soloveitchik, “A Tribute to the Rebbitzen of Talne,” Tradition 17:2, 73. 18 we may have been trying to forget, despite the difficulties that arise, so we can feel redeemed and cleansed.49 We cannot allow ourselves to hide behind the mask of Adam’s va-ehabe, for which he was cursed with anonymity.50 Let us rather find our path to historical legacy. Conclusion The Rav makes the following statement in Kol Dodi Dofek: The teaching of the rectification of suffering – when it is put into practice – demands of the sufferer both courage and discipline. He must find within himself and draw upon prodigious resources, and subject himself to a rigorous self-examination and self-evaluation, untainted by the slightest hint of partiality or self-indulgence; he must contemplate his past and envisage his future with complete and unwavering honesty.51 Who is the sufferer here? On the surface it is the victim going through the suffering experience. The hidden message here is really to the educator. It is the person at the front of the classroom who must have the “courage and discipline,” must “draw upon prodigious resources,” and more, must have unwavering confidence to fill in the potholes on the road of the lesson ahead. We must recognize that the sufferer and teacher alike are receiving calls to responsibility: the sufferer has a personal obligation, and we as teachers have a communal one. Both must answer Hineni: I am ready to take action. Soloveitchik, “A Tribute,” 73. Soloveitchik, “Redemption, Prayer, Talmud Torah,” 61. 51 KDD, 64. A more explicit statement is made in OOW, 118: “The religious teacher is charged with the task of teaching the apocalyptic experience to cosmic man. It is a difficult but great task.” 49 50 19 Bibliography Brovender, Chaim. “Towards Ahavat Hashem: Art and the Religious Experience.” In Wisdom From All My Teachers: Challenges and Initiatives in Contemporary Torah Education, edited by Jeffrey Saks and Susan Handelman, 49-73. Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 2003. Handelman, Susan. “We Cleverly Avoided Talking About God: Personal and Pedagogical Reflections on Academia and Spirituality.” Courtyard: A Journal of Research and Thought in Jewish Education 1 (1999): 101-120. Rakeffet-Rothkoff, Aaron. The Rav: The World of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik. Edited by Joseph Epstein. 2 vols. New Jersey: Ktav Publishing House, 1999. Schreiber, B. David. Sefer Noraot ha-Rav. Vol. 7. Shene derashot al inyane yamim tovim u-megillat ester. Me-et ha-Gerid ha-Levi Solovaits’ik. Forthcoming. Schremer, Oded. “Toward Understanding Buber’s I-Thou and I-It Dichotomy in the Context of Education.” Journal of Jewish Education 2 (1984): 212-230. Simkovich, Moshe. “Teaching Rabbi Soloveitchik’s Thought in the High School Classroom.” In Wisdom From All My Teachers: Challenges and Initiatives in Contemporary Torah Education, edited by Jeffrey Saks and Susan Handelman, 341-359. Jerusalem: Urim Publications, 2003. Soloveitchik, Joseph B. “A Tribute to the Rebbitzen of Talne,” Tradition 17:2 (1978): 73-83. -------------------------- “Kol Dodi Dofek: Is is the Voice of My Beloved That Knocketh.” In Theological and Halakhic Reflections on the Holocaust, edited by Bernard Rosenberg, 51-73. New Jersey: Ktav Publishing House, 1992. -------------------------- On Repentance. Edited by Pinchas Peli. Jerusalem: Orot Press, 1981. -------------------------- “Out of the Whirlwind.” In Out of the Whirlwind: Essays on Mourning, Suffering and the Human Condition, edited by David Shatz, Joel B. Wolowelsky and Reuven Ziegler, 116-150. New Jersey: Ktav Publishing House, 2003. 20 -------------------------- “Redemption, Prayer, Talmud Torah.” Tradition 17:2 (1978): 55-72. Twersky, Isadore. “What Must Be Taught – and Why?” In Visions of Jewish Education, edited by Seymour Fox, Israel Scheffler and Daniel Marom, 47-76. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003. Unterman, Yael. “If You Seek Him With All Your Heart: Nurturing Total Individual Growth in Yeshivah.” In Wisdom From All My Teachers: Challenges and Initiatives in Contemporary Torah Education, edited by Jeffrey Saks and Susan Handelman, 159-178. Jerusalem: Urim Publications (2003).