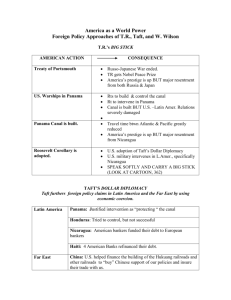

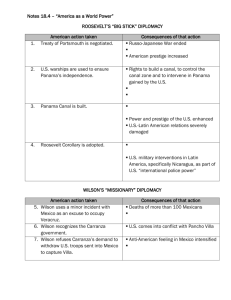

Dollar and Moral Diplomacy Notes

advertisement

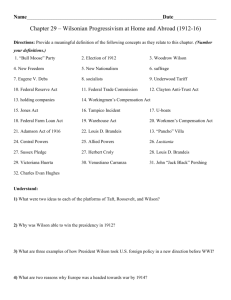

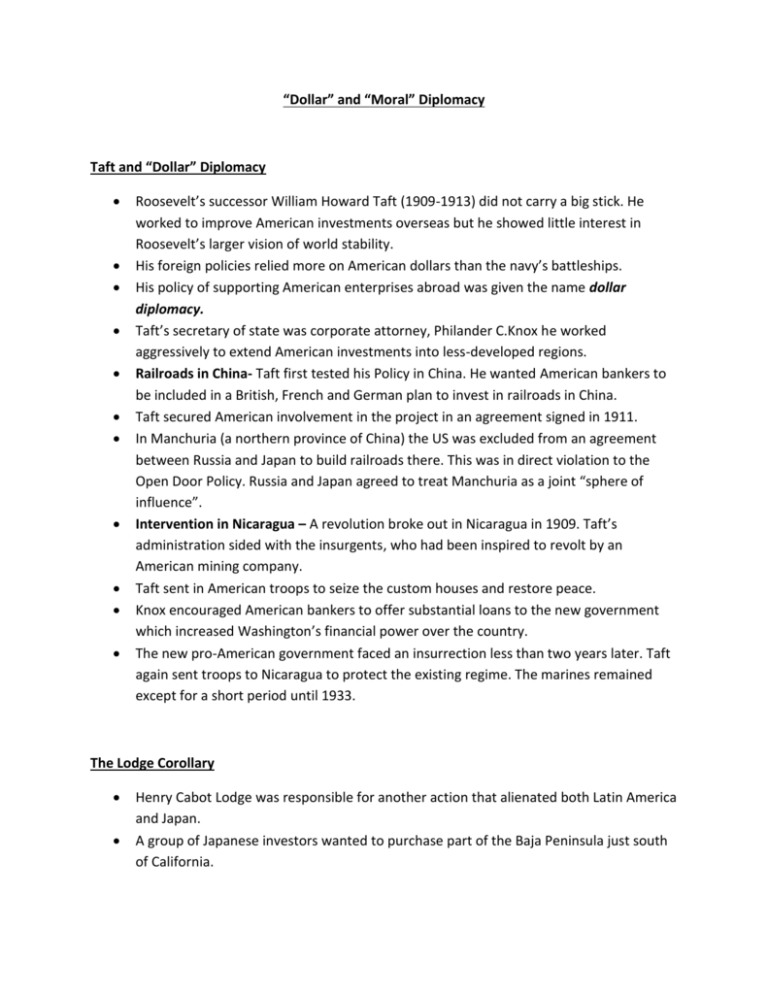

“Dollar” and “Moral” Diplomacy Taft and “Dollar” Diplomacy Roosevelt’s successor William Howard Taft (1909-1913) did not carry a big stick. He worked to improve American investments overseas but he showed little interest in Roosevelt’s larger vision of world stability. His foreign policies relied more on American dollars than the navy’s battleships. His policy of supporting American enterprises abroad was given the name dollar diplomacy. Taft’s secretary of state was corporate attorney, Philander C.Knox he worked aggressively to extend American investments into less-developed regions. Railroads in China- Taft first tested his Policy in China. He wanted American bankers to be included in a British, French and German plan to invest in railroads in China. Taft secured American involvement in the project in an agreement signed in 1911. In Manchuria (a northern province of China) the US was excluded from an agreement between Russia and Japan to build railroads there. This was in direct violation to the Open Door Policy. Russia and Japan agreed to treat Manchuria as a joint “sphere of influence”. Intervention in Nicaragua – A revolution broke out in Nicaragua in 1909. Taft’s administration sided with the insurgents, who had been inspired to revolt by an American mining company. Taft sent in American troops to seize the custom houses and restore peace. Knox encouraged American bankers to offer substantial loans to the new government which increased Washington’s financial power over the country. The new pro-American government faced an insurrection less than two years later. Taft again sent troops to Nicaragua to protect the existing regime. The marines remained except for a short period until 1933. The Lodge Corollary Henry Cabot Lodge was responsible for another action that alienated both Latin America and Japan. A group of Japanese investors wanted to purchase part of the Baja Peninsula just south of California. Fearing that Japanese investors wanted to purchase land Lodge introduced and the Senate passed in 1912, a resolution known as the Lodge Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. The resolution stated that non-European powers, such as Japan, would be excluded from owning territories in the Western Hemisphere. Taft opposed the corollary, which also offended Japan and angered Latin American countries. Woodrow Wilson and “Moral” Diplomacy In his campaign for president in 1912, the Democratic candidate Woodrow Wilson called for a New Freedom in government and promised a moral approach to foreign affairs. Wilson said he opposed imperialism and the big-stick and dollar-diplomacy policies of his Republican predecessors. Wilson entered the presidency with little interest or experience in international affairs. He faced international challenges unmatched by any president before him. The greatest test of Wilsonian diplomacy did not occur until WW1 many of the qualities he would bring to that ordeal were evident in his foreign policies from his first moments in office, particularly in his dealings with Latin America. In his first term as president (1913-1917) he had limited success applying a high moral standard to foreign relations. He and secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan hoped to demonstrate that the US respected other nations’ rights and would support the spread of democracy. Righting past wrongs – He wanted to demonstrate that his presidency was opposed to self-interest imperialism. Wilson took steps to correct what he viewed as wrongful policies of the past. 1) The Philppines – Wilson won passage of the Jones Act of 1916 which 1) granted full territorial status to that country, 2) guaranteed a bill of rights and universal male suffrage to Filipino citizens and 3) promised Philippine independence as soon as a stable government was established. 2) Puerto Rico – An act of Congress in 1917 granted US citizenship to all the inhabitants and also provided for limited self-government. 3) The Panama Canal – Wilson persuaded Congress in 1914 to repeal an act that had granted US ships an exemption from paying the standard canal tolls charged to other countries. Wilson’s policy on Panama canal tolls angered American nationalists like Roosevelt and Lodge but pleased the British who had strongly objected to US exemption. Conciliation treaties – Wilson’s commitment to the ideals of democracy and peace was shared with his secretary of state, William Jennings Bryan. Bryan’s pet project was to negotiate treaties in which nations pledged to 1) submit disputes to international commissions and 2) to observe a one-year cooling-off period before taking military action. Bryan arranged with Wilson’s approval thirty such conciliation treaties. Military Intervention in Latin America Wilson’s commitment to democracy and anticolonialism had a blind spot with respect to the countries of Central America and the Caribbean. Wilson went far beyond Roosevelt and Taft in his use of US marines to settle financial and political problems in Latin America. Throughout his presidency he kept marines in Nicaragua. He signed a treaty with that country’s government ensuring that no other nation would build a canal there. The treaty also made sure that the US could intervene in Nicaragua’s internal affairs to protect American interests. The US had already seized control of the finances of the Dominican Republic in 1905. The US established a military government there in 1916 when the Dominicans refused to accept a treaty that would turn it into an American protectorate. The military occupation lasted eight years. In Haiti, which shared the island of Hispaniola with the Dominican Republic, Wilson landed marines in 1915 to quell a revolution in the course of which a mob had murdered an unpopular president. American marines remained there until 1934 and American officers drafted the constitution adopted in 1918. Wilson was afraid that the Danish West Indies was about to fall into the hands of Germany, he brought the colony from Denmark and renamed it the Virgin Islands. In all of these actions Wilson was displaying an approach to Latin America similar to that of Roosevelt and Taft. He argued that such intervention was necessary to maintain stability in the region and protect the Panama Canal. Conflict in Mexico Wilson’s moral approach to foreign affairs was severely tested by a revolution and civil war in Mexico. For many years American businessmen had been establishing an enormous economic presence under the friendly auspices of the corrupt dictator, Porfirio Diaz. In 1910 Diaz was overthrown by the popular leader Francisco Madero who promised democratic reform but was hostile to American businesses in Mexico. The US quietly encouraged a reactionary general Victoriano Huerta to depose Madero early in 1913. The Taft administration in its last weeks in office prepared to recognize Huerta’s regime and a friendly environment for American investments in Mexico. Before it could do so, the new government murdered Madero and Wilson took office on Washington. The new president announced he would never recognize Huerta’s “government of butchers”. The conflict dragged on for years. Wilson hoped that refusing to recognize Huerta would topple the regime and bring to power the opposing constitutionalists led by Venustiano Carranza. Huerta, with the support of American business interests, established a full military dictatorship in 1913. The president became more assertive and in 1914 a minor naval incident provided him with an excuse for open intervention. To aid a revolutionary faction that was fighting Huerta, he asked for an arms embargo against the Mexican government and sent a fleet to blockade the port of Veracruz. An officer in Huerta’s army arrested several US soliders from the USS Dolphin who had gone ashore in Tampico. The men were immediately released but the American admiral was not happy with the apology he received and he demanded from Huerta a twentyone gun salute to the American flag. Huerta refused and Wilson used this incident as a pretext to seize the Mexican port of Veracruz. Wilson thought it would be bloodless but Americans killed 126 Mexican troops and suffered 19 casualties of their own. At the brink of war Wilson began to look for a way out. It was averted when South America’s ABC powers, Argentina, Brazil and Chile, offered to mediate the dispute. This was the first dispute in the Americas to be settled through joint mediation. Wilson’s show of force strengthened Carranza’s position and he captured Mexico City in August and forced Huerta to flee the country. It seemed the crisis might be over. Wilson was not satisfied he reacted angrily when Carranza refused to accept American guidelines for the creation of a new government and he briefly considered giving his support to Pancho Villa, Carranza’s lieutenant, who was now leading a rebel army of his own. When Villa’s military position deteriorated Wilson abandoned him and in October 1915 granted preliminary recognition to the Carranza government. This created another crisis. Villa was angry at what he considered an American betrayal and he retaliated in January 1916 by taking 16 American mining engineers from a train in northern Mexico and shooting them. Two months later he led his soldiers (or “bandits” as the US called them) across the USMexico border and murdered seventeen more Americans in Texas and New Mexico. With the permission of the Carranza government, Wilson ordered General John J. Pershing to lead an American expeditionary force across the Mexican border in pursuit of Villa. This force was in northern Mexico for months and never found Villa. President Carranza eventually protested the American presence in Mexico and his forces engaged in two skirmishes in which 40 Mexicans and 12 Americans died. The US and Mexico again stood on the brink of war. At the last minute in January 1917, Wilson drew back and quietly withdrew Pershing’s troops because of the growing possibility of US entry into WW1. In March 1917, Wilson granted formal recognition to the Carranza regime.