Giuseppe (Fortunino Francesco) Verdi

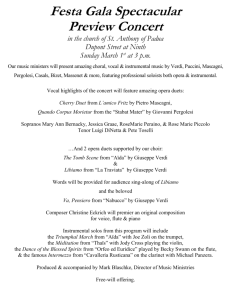

advertisement

Giuseppe (Fortunino Francesco) Verdi (1813-1901) I. Importance and life A. Verdi is the most important Italian composer of the middle to the end of the 19th century. He inherited the traditions of Bellini and Donizetti and the grand opera practice of Meyerbeer, and raised the form to new heights. B. Verdi was criticized, during his life and afterward, of being overly simple and melodramatic. His operas have stood the test of time, however, and are a major staple of the repertoire throughout the world. Although Bellini and Donizetti wrote many more works, more Verdi operas are in the repertoire. C. Verdi was born 1813 in Le Roncole, a small Tuscan town near Busseto, which is in the Duchy of Parma. At the time of Verdi’s birth, Europe was in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Era—Verdi was born under a French passport. His father was an innkeeper. D. At 20, Verdi went to Milan to continue his studies. He was rejected from the Conservatory (various reasons given—too old, poor piano proficiency, poor counterpoint). He returned to Busseto to become the town’s maestro di musica. E. Verdi sought private study in counterpoint and obtained Barezzi as a patron. He married Margherita Barezzi in 1836. Their two children died in infancy of typhoid. G. His first operatic success was Oberto, which was premiered at La Scala. Merelli, the impresario, offered a contract for two more operas. H. His second opera, Un giorno di regno, was a failure. Margherita died in 1840 while he was composing it. I. Nabucco (1842) was a success, however, and it made him famous. Strepponi sang the role of Abigaille. J. In 1851, Verdi became more intimately involved with the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi. They lived together for about eight years before they were married, which was regarded as scandalous at the time. Strepponi was divorced and Verdi refrained from marrying her for some time out of deference to his family. Verdi wrote to his former father-in-law of the affair: “I have nothing to hide. In my house there lives a lady, free, independent, a lover of solitude, so am I...Neither I nor she owes to anyone at all any account of our actions...I demand liberty of action for myself...since my nature rebels against conformity.” Verdi’s deep sympathy for Violetta, and his characterization of Germont, may have arisen from his personal experience. K. Verdi contemplated retiring several times—he was wealthy from the operas he had composed, owned an estate and was appointed Senator for Life after the success of the Risorgimento (political movement to unify Italy). Strepponi may have been the one to persuade him to return composition in the early 1860s, and it was his publisher Riccordi who did the same, 25 years later. L. Verdi composed 26 operas, a string quartet, a Requiem Mass and several late choral works. He was politically active (his operas were identified with the drive toward national unity) and a generous man (he set up a home for retired musicians). His name became associated with the rallying cry and acronym Viva VERDI (Viva Victor Emmanuel, Roi D’Italia.) M. Unlike Wagner, Verdi never wrote any of his own libretti, he took an active hand in their construction. He preferred current topics and plays and historical dramas for settings, as well as opera texts based on Shakespeare, of which he set three (see below). Several operas are based on French works (Rigoletto and La traviata). II. Important Operas and other works A. Nabucco. Fp. 1842, libretto by Solera, based on a play by Anicet-Bourgeos and Cornu. Story: The setting is ancient Babylonia. King Nebuchadnezzar oppresses the Jews, who long to return to the land of Israel. The most famous number from the opera is the “Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves” which became identified with the Risorgimento (resurgence). There is a story that when the chorus began to rehearse this number, the carpenters put down their hammers and came to the stage to listen. In the hushed silence, people knew that Verdi had a success. Italians identified with the exiled Hebrews, and also longed for a homeland. The text, in part, reads: Fly, thought, on wings of gold; go settle upon the slopes and the hills where the sweet airs of our native soil smell soft and mild! ...Oh, my country, so lovely and lost! Oh remembrance so dear yet unhappy! B. Macbeth. Composed 1846-47 on a libretto by Piave, based on a prose translation of the play. Verdi did not read the original until after the opera was completed. He revised it in 1865 for Paris. The story follows the original play in most details, except that the Three Witches are replaced by a Witches’ Chorus. Macbeth is considered a flawed masterpiece. C. La traviata. Composed 1848, Fp.1853, based on the La dame aux Camélias by Alexander Dumas, fils. The story has been used as the basis of Camille and the Baz Luhrman film Moulin Rouge! Violetta is a courtesan who suffers from tuberculosis. She falls in love with Alfredo, a rich young man and they retire from the mad life of Paris for the country so that Violetta might recover. Alfredo’s father, Germont, appeals to Violetta to give him up, which she agrees to do. Violetta returns to Paris. Alfredo, feeling betrayed, humiliates Violetta at the Casino. Later, Germont tells Alfredo the truth about Violetta’s sacrifice. Alfredo rushes to her deathbed, but it is too late. The basic elements of the plot can be seen to have autobiographical significance to Verdi (see I.J., Strepponi, above). There are numerous famous arias and D. E. F. G. H. I. ensembles from this opera which are performed frequently as concert hall favorites, and the opera is one of the most-performed of Verdi’s operas. Rigoletto. Fp. 1851 on a libretto by Piave based on the play Le roi s’amuse by Victor Hugo. Verdi chose the play, which had already encountered problems with the censors. Verdi and Piave had great difficulties with the censor over the subject matter. Story: Rigoletto is the hunchbacked Court Jester of the Duke of Mantua. He has a beautiful daughter, Gilda, who he keeps secreted away, fearing the Duke’s amorous and treacherous tendencies. Gilda meets and falls in love with the Duke. Rigoletto hires Sparafucile to kill him. Gilda learns of the plot and takes the Duke’s place. Sparafucile delivers the body of the dying Gilda to Rigoletto in order to receive his payment. Rigoletto is despondent. The Duke’s aria “La donna e mobile” is one of the most famous arias ever written and the “Rigoletto Quartet”, which features the four main characters, is also deservedly famous. Verdi uses reminiscence motives. Il trovatore. Fp. 1853 on a libretto by Bardare and Cammarano, based on the play “El Trobador” by Gutiérrez. Traviata, Rigoletto and Trovatore are often seen as a triptych of operas that mark Verdi’s development into a mature style. These three exemplify Verdi’s idea of musical drama, which stands in contrast to Wagner. Verdi viewed music drama as an amalgam of heterogeneous elements which explored a socially and/or culturally complex situation. Verdi also combined comic and tragic elements. Les vespers siciliennes, Fp. 1855, based on a libretto by Duveyrier and Scribe. The overture to this opera, also known as I Vespri Siciliani, is a concert hall favorite. Les vespers and Don Carlos are grand operas which premiered in Paris. La forza del destino, Fp. 1862 in St. Petersburg, Russia, on a libretto by Piave, based on a scene from Schiller’s Wallensteins Lager. The story is set in Spain. This overture is also a concert hall favorite. In La Forza, as well as in Un ballo in maschera, Verdi introduced comic roles. Aida, Fp. 1871 at the Khedivial Opera House in Cairo, on a libretto by Ghislanzoni, based on a story by Mariette. Story: Aida is an Ethiopian princess, who is captured and brought to Egypt. Radames, a military officer, struggles between his love for Aida and his loyalty to the Pharaoh. Radames is loved by Amneris, the Pharoah’s daughter. Amonasro, the Ethiopian King and Aida’s father, flees with her and Radames, who allows the escape, is imprisoned for treason. Radames rejects Amneris’ love, but she still pleads for Radames’ life. He is found guilty and condemned to be buried alive. Aida chooses to die with Radames, and hides in the pyramid-tomb. The sing a farewell to life and life’s tragedies as the Amneris weeps, above, accompanied by the priest’s chorus. Aida is the epitome of grand opera. Productions often include horse-drawn chariots, huge choruses, elephants and camels and a large choir of herald trumpets onstage. With the composition of Aida, Verdi intended to retire. Requiem, composed in 1874. Parts of the Manzoni Requiem were first composed for a requiem Verdi began in 1868 in memory Rossini, but did not complete. The earlier project was to be a compilation of work by various composers. When the great Italian humanist Alessandro Manzoni died, Verdi took up the work again, revising and incorporating his earlier work (which was never published). The Manzoni Requiem follows the Latin Mass and includes a Kyrie, Dies Irae, Offertorio, Agnus Dei, Lux Aeterna and a Libera me. J. Otello, Fp. 1887, marks Verdi’s return to composition after nearly a 12-year hiatus. The libretto is by Arrigo Boito, based the Shakespeare play Othello. Bioto, a wealthy man, composer, man of letters and an avid Wagnerite in his youth, had been a bitter enemy of Verdi’s in earlier days. It therefore required some peace-making by Riccordi to make the project happen. Verdi was so thrilled with Bioto’s libretto that he agreed. Ironically, the work is a continuous music drama with reminiscence motifs, somewhat along Wagnerian lines. The action follows the play in its major outline, omitting the opening scene of the play and telescoping the denouement. Iago is one of Verdi’s greatest villains. K. Falstaff, Fp.1893 at La Scala, on a libretto by Bioto, based on Shakespeare’s character as he appears in Henry IV, V and The Merry Wives of Windsor. Some writers believe that the opera is greater than The Merry Wives of Windsor, upon which it is mostly based. Falstaff follows the action of the play in most details, and has been critically acclaimed for its refinement and sophistication. It is remarkable that Verdi undertook to compose such as massive score at the age of 80. It ends with a brilliant fugue “Tutto nel mondo é burla” (all the world is a joke). Story: Falstaff plans to escape his dire economic straits by seducing one or the other of two rich women (Mistresses Ford and Paige). He sends them both the same letter! The women compare the love letters, have a good laugh, and plot a series of revenges on both Falstaff and their jealous husbands. In a subplot, Nanetta, daughter of the Fords, plots to marry Fenton against her father’s wishes. In the end, daughter and betrothed are married and Falstaff is suitably humiliated by the entire village. Falstaff, pleased the plot has backfired on Ford and resulted in Nanetta’s nuptials, leads the town in a fugue celebrating the foolishness of the world. III. Style A. Verdi orchestration is masterful. He was able to control and balance large ensembles on stage and off-stage with a essentially conventional orchestra in the pit. B. Although his harmonic language is relatively simple, when compared to Wagner, Verdi was keenly aware of large-scale harmonic motion so that scenes and acts have dramatic and musical dynamism. C. The center of melodic is in the voice rather than the orchestra, as was typical of mature Wagner. The orchestra may accompany the voice, double the melodic line, or play sophisticated counterpoint against the main melodic line which is carried by the voice(s). D. Verdi adhered to “number opera” construction for earlier works, but moved toward a more continuous musical texture with the late works. E. Verdi worked with his many librettists to insure that the plots were stripped of all unnecessary characters and detail, so that he could concentrate on the dramatic action, which was his strength. F. Verdi wrote brilliantly for the voice. Although his music can be immensely difficult to sing, it is “singable”, with well-approached high notes, and excellent text-underlay. III. Structure—Verdi follows the “Double-aria” structure he learned from Rossini A. Instead of a recitativo secco, scenes open with a “scena” recitative B. Primo tempo follows (1st movement) usually in a slow, cantabile tempo C. Tempo di mezzo (middle movement) may incorporate and ensemble D. Cabaletta is the final movement, often fast E. In a duet, the opening scena is followed by a “tempo attacca”, with the rest of the aria pattern to follow. This creates an alternating action-stasis-action-stasis pattern. III. Periods A. Early operas—first period culminates in 1853 with Il trovatore and La traviata B. Middle period—includes ventures into grand opera, culminating in Aida and the Requiem C. Late period—the two Shakespeare operas, late sacred choruses. Quotes—Verdi on the primacy of the dramatic action over the musicality of the work: Verdi: “To copy reality is a good thing, but to invent reality is better, much better. A contradiction may seem to exist in these three words “to invent reality”, but just ask Papa Shakespeare.” Direct, primal expression of human emotion was the greatest artistic goal, in Verdi’s view. Although his libretti were in written in verse (for reasons of comprehension and singability), we have record of his correspondence to the his librettists constantly asking them to pare down the text. In this regard, Verdi’s beliefs echo Hamlet’s instructions to his players: Hamlet: “Suit the action to the word, the word to the action, with this special instruction, that you o’erstep not the modesty of nature. Verdi inherited the set-piece construction of bel canto opera of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti, but he reformed it. This reform can first be seen in Verdi’s first Shakespeare opera, Macbeth, in which objected to the beautiful Tadolini who was cast as Lady Macbeth. He wrote: Verdi: “Tadolini has a beautiful, lovely figure and I would like Lady Mabeth brutish and ugly. Tadolini sings to perfection, and I would like a Lady Macbeth who doesn’t really sing. Tadolini has an astonishing, clear, limpid, potent voice, and I would like in a Lady a harsh, suffocated, veiled voice. Tadolini’s voice is angelic; I would like Lady’s voice to seem diabolical.” In other words, the bel canto opera voice was not what Verdi sought. He wanted a singing actor. He also (gradually) abandoned the highly ornamental style of Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. They wanted to give their singers room to sing, while Verdi wanted to give them room to act. The dichotomy between Verdi and Wagner is that Verdi sought realism, genuine and vigorous emotion, visceral reaction, and directness, while Wagner sought theory, allegorical meaning, elevation of reality to the world of philosophy and extreme artistic polish. In a Verdi scene, the action seems to take place in real time, while in a Wagnerian scene, the action often seems to move in slow motion. Verdi’s characters think and react like real people, while speed of Wagnerian drama moves in a kind of suspension which allows time for the viewer to contemplate. Therefore, the Verdi orchestra accompanies the scene while the Wagner orchestra provides a commentary and reflection on the action. Therefore, the typical Wagnerian plot is rooted in myth and legend because these characters are close to archetypes, while the typical Verdi story came from either a Shakespearean play (although it is true that Shakespeare’s characters are close to their archetypal roots), or often an historical setting, or a novel. It is no wonder than Verdi chose Macbeth as his first Shakespeare project—it is the second shortest of Shakespeare’s 38 plays, and is distinguished by its simplicity and the tautness of the action; it is not burdened with subplots. Verdi wrote that Macbeth has only three characters: Macbeth, Lady Macbeth and the Witches. Verdi: “I want plots that are great, beautiful, varied, daring...daring to an extreme, new in form and at the same time adapted to composing...another person would perhaps not have composed (La traviata) because of the costumes, because of the period, because of a thousand other foolish objections. O did it with particular pleasure. Everyone cried out when I proposed to put a hunchback on stage. Well. I was overjoyed to compose Rigoletto, and it was just the same with Macbeth, and so on. Ironically, both Verdi and Wagner sought to destroy the set-piece construction of opera as they inherited it, but they went at the problem from opposite directions.