- Teaching American History

advertisement

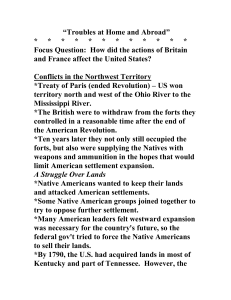

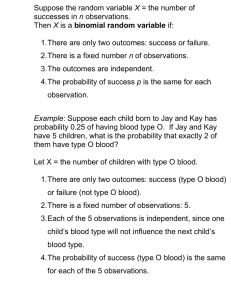

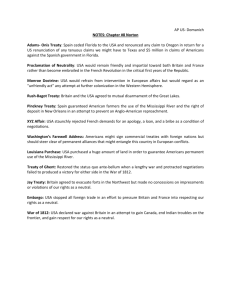

The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= The Crisis of American Diplomacy, 1793-1807 Lesson #1: The United States, Great Britain, and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1796 I. Introduction Matters of foreign policy dominated American political concerns in the final decade of the eighteenth century. In 1793 war broke out between Revolutionary France and Great Britain, and American commercial interests became a target for both countries. This lesson will examine the ways in which Great Britain challenged American sovereignty. By looking at government documents and playing out commercial scenarios students will explore American interpretations of European actions, as well as the ways in which the George Washington administration chose to respond. Particularly, they will examine the 1794 effort by John Jay to settle the situation through diplomatic negotiation, and the resulting growth of domestic democratic activism it spawned. II. Guiding Questions How did British foreign policy decisions challenge American sovereignty between 1793 and the ratification of the Jay Treaty? Why was the Jay Treaty so controversial, and how did it stimulate internal democratic development? III. Learning Objectives Upon completion of this lesson, students should be able to: recognize the impact of the French Revolution upon American diplomacy explain British attacks on American neutrality explain the diplomatic logic behind the Jay Treaty articulate domestic political opposition to the Treaty IV. Background Information for Teachers The outbreak of the French Revolutionary wars in 1792 posed a critical problem for AngloAmerican relations. Was the U.S. alliance with France, which dated back to 1778, still in effect? Did America’s nascent economy require the maintenance of close ties with Britain? Ultimately, President George Washington decided that the United States was in no condition to engage in military confrontation and decided on a position of neutrality. This official position was the beginning of an effort by the United States to remain neutral in European affairs that would last until the outbreak of war in 1812. Neutrality proved to be difficult to maintain, however, particularly in light of the fact that both Britain and France consistently interfered with American affairs. 1 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= The first such interference occurred in April 1793, when Edmond Charles Genet arrived as French minister to the United States. Genet’s mission was to ensure American support for France in the European wars, and he was chagrined to find that President Washington insisted on strict neutrality. Rather than waiting for Washington’s approval, he commissioned American privateers to harass British shipping and enlisted Americans to move against Spanish interests in New Orleans. He also opened the French Caribbean to American shipping, a move designed to enlighten the United States to free trade with France as opposed to restricted trade with Britain. The British response was swift and strong. In 1793, and particularly in light of Genet’s efforts, they began to seize American vessels loaded with French cargo. The Royal Navy formally justified its action by applying the doctrine that enemy property on the high seas was legal to take, even if carried in a neutral vessel. To make matters worse, they also began searching American ships for sailors who had deserted the Royal Navy, and if necessary removed said deserters for reentrance into British service. Known as impressment, this practice amounted to the kidnapping of American citizens. News of captures (both vessels and sailors) deeply concerned members of the emerging Democratic-Republican political coalition. They wanted to fight the British with trade restrictions, and possibly more. Federalists, who received particularly strong support from New England merchant interests, were less inclined to agree. They understood that American trade depended upon a good relationship with Britain. Hoping to ease tensions, in 1794 Washington sent John Jay as an envoy to London. Jay eventually negotiated a treaty (http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/diplomacy/britain/jay.htm) that, among other things, got the British to evacuate northwest outposts and gave a limited right of American vessels to trade with the British West Indies (American trade had been barred since 1783). On the North Atlantic Britain reopened trade of American farm goods for British manufactures, while the United States conferred upon Britain the status of “most favored nation.” Finally, the United States agreed to repay pre-Revolution debt owed by Americans to British creditors (eventually, the settled-upon figure was 600,000 pounds), while Great Britain agreed to compensate Americans for illegal captures of ships (eventually, the settled-upon figure was 1.3 million pounds). The treaty left impressment and other maritime issues to future negotiation, and pointedly did not address an American demand that Britain pay for slaves carried off during the Revolution. Jay’s Treaty had both positive and negative aspects. On the one hand, American commerce revived and the government successfully avoided open confrontation with Britain. On the other hand, it seemed to nurture a de facto commercial alliance with the British, despite the government’s stated commitment to neutrality. France particularly took note of this new alliance, as did an increasingly vocal opposition in the United States. Through the summer of 1794 public meetings, memorials, petitions, addresses, resolutions, and remonstrances were held throughout the country. Burning effigies of John Jay were common. The Virginia Legislature challenged the treaty’s constitutionality. Congress considered hearings to investigate the mechanics of the treaty negotiation. The Senate eventually ratified it, albeit with a bare majority. 2 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= When Washington signed the treaty, his public support dropped lower than at any time in his political career. Although such intense opposition quickly subsided, the uproar underscores that ordinary Americans were coming to understand the democratic potential of the American Revolution. Over the course of the 1790s these people used civic outbursts both to join the political process and to establish links between local events and an emerging national political culture. Through effigy burnings, parades, Fourth of July toasts, petitions, newspaper debates and other popular actions ordinary Americans showed an increasing commitment to affect the political debates taking place in Philadelphia. V. Preparing to Teach this Lesson Review the lesson plan. Locate and bookmark suggested materials and links from EDSITEmentreviewed websites used in this lesson. Download and print out selected documents and duplicate copies as necessary for student viewing. Alternatively, excerpted versions of these documents are available as part of the downloadable PDF file. Download the Text Document for this lesson, available here as a PDF file. This file contains excerpted versions of the documents used in the various activities, as well as questions for students to answer. Print out and make an appropriate number of copies of the handouts you plan to use in class. Analyzing primary sources If your students lack experience in dealing with primary sources, you might use one or more preliminary exercises to help them develop these skills. The Learning Page at the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress includes a set of such activities. Another useful resource is the Digital Classroom of the National Archives, which features a set of Document Analysis Worksheets. VI. Suggested Activities (three total) Activity #1: The Perils of Neutrality The lesson begins with a game called “Contraband.” The game is designed to help students understand the dangers that the United States faced during the 1790s, as a neutral power hoping to trade with both sides in a major war. To prepare for the game, be sure to read the rules (available on pages 1-4 of the Text Document) and print enough copies of pages 1-8 of the Text Document (the rules, game board, game pieces, and concluding worksheet) for each group that will play the game. “Contraband” is designed for three players (or four if the optional “Barbary Pirates” rule is used), so plan accordingly. For best results, print pages 5 and 6 (the board and the pieces) on lightweight cardstock rather than ordinary paper. Cut out the pieces, then in the case of U.S. Merchant Ships fold them in half 3 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= vertically and glue them shut, so that the image of the ship appears on one side, and the British or French flag appears on the reverse. Also, it will be necessary to find one six-sided die for each group of students that will be playing the game. At the start of the next class session, inform students that it is 1793, and that Great Britain and France are at war. The United States is officially neutral in this conflict, but hopes to trade with both sides. While the British and French both very much want to trade with the United States, each side wants to prevent the Americans from trading with its enemy. To begin, students are to read President Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality (1793) (http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=622), located at the EDSITEment-reviewed site Teaching American History, as well as on page 9-10 of the Text Document. As they read they should answer the following questions, found in worksheet form on page 10 of the Text Document. List the belligerents. What constitutes “conduct friendly and impartial toward the belligerent powers”? What constitutes behaviors that would result in “punishment or forfeiture under the law of nations, by committing, aiding, or abetting hostilities”? What is the goal of Washington’s proclamation? Next, divide the class into groups of three or four and distribute to each group the game rules, boards, and pieces as well as the worksheet on pages 7-8. Go through the rules with the students, and then allow the class approximately a half-hour to complete the game, available on the worksheet. At the conclusion of the game, each group should answer the following questions. Who won the game, and why do you think it worked out this way? Did the U.S. Player choose to trade with one side more than the other? If so, with which one, and why? Did the U.S. Player tend to use any of its ports more than the others? If so, which one, and why? Did the U.S. Player decide at any time to keep his or her merchant ships in port, or in U.S. territorial waters? If so, when and why? Did the British or French players at any time decide not to inspect a U.S. merchant ship when he or she had the chance? If so, when and why? How would the game have been different if the United States had a Squadron like that of the British and French? If the Barbary Pirate option was used, what effect did this have on the game? If the Naval Combat option was used, what effect did this have on the game? Activity #2: Neutral or Belligerent? The outbreak of war between France and Great Britain in 1793 provided the United States with its first significant foreign policy challenge. Was the young republic to continue its treaty with 4 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= France which dated to 1778? Or did the need for economic recovery mean closer ties with Britain? President George Washington decided in April of 1793 to take a position of neutrality. Siding with either country could lead to war with the other, and the United States was in no condition to engage in a military confrontation. In this activity, students will read selected documents from the EDSITEment-reviewed site Teaching American History that discuss the various reactions of Americans to the events on the high seas as well as the response of the President. First, students will read the selected documents and answer the questions associated with each. This activity can also be found in worksheet form on pages 11-16 of the Text Document. Editorial in The Gazette of the United States (March 13, 1794) http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1728 Does the author advocate following a position of neutrality or belligerency? What are the author’s arguments for peace or war? According to the author, how has the U.S. failed to follow a path of neutrality? What does the author argue are the consequences of following such a path? Editorial in The Gazette of the United States (1794) http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1729 Does this letter support the French or the British? Why does the author feel that the spread of republican government would threaten the British? List some of the ways that the author views this outlook had an impact on the United States According to the author, how should Congress respond? Editorial in the Columbian Centinel (January 4, 1794) http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1731 Does the author advocate following a position of neutrality or belligerency? How will this treatment of U.S. merchants affect other areas of the economy? What does the author suggest as a course of action for the U.S.? Letter to the Editor of the Boston Gazette (1794) (first document on page) http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1732 Does the author advocate following a position of neutrality or war? In the opinion of this author how has the U.S. responded “foolishly” to these events? Why does the author feel that actions must be taken immediately? Editorial in the Virginia Chronicle (March 29, 1794) (fourth document on page) http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1732 5 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= List some of the reasons why this author seems so confused about U.S. neutrality. Next, students should create two lists. The first should cite reasons why the United States should remain truly neutral and the second should cite reasons for war or alliance with either Britain or France. This chart can be found on page 17 of the Text Document. After students have generated their lists, have them engage in a silent. Divide students into groups of two, flipping a coin to decide which side they should support. Using the worksheet on page 18 of the Text Document, the student supporting neutrality should begin by writing in the left-hand column a reason why he or she believes it is a good idea. Then the student supporting alliance or war should write in the right-hand column a reason why he or she advocates their position. This silent debate should continue until one side or the other runs out of reasons. Conclude this activity by having students write their own “letter to the editor” in which they state their opinion for or against neutrality. The letters should be around 500 words in length and use arguments from the above articles to support their opinion. Activity #3: An offer you can’t refuse? Jay’s Treaty reassessed. Anglo-American relations continued to worsen during the early 1790’s due to the wars of the French Revolution. Americans were angry because of the impressments of U.S. sailors, seizure of American ships, and the occupations of western forts by the British. In 1794, Chief Justice John Jay was sent to England to negotiate a solution to these issues. The agreement Jay returned home with caused a heated response from members of President Washington’s cabinet. Cabinet divisions in turn reflected broader debates over the Treaty. By the fall of 1794 opposition had become so strong that it helped establish parameters for the emerging political division between Federalists and Democratic Republicans. In activity 3, students will assess the domestic political opposition to the Jay Treaty. Students will begin by reading excerpts from the Jay Treaty (http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/diplomacy/britain/jay.htm) on pages 19-22 of the Text Document. Students should read the excerpt and then summarize the main themes and write them on the corresponding chart on pages 22-23. As a whole class, discuss the main points to this treaty. Some of these may include: Evacuation by the British of western forts. Compensation by the British of American ship owners. Most favored nation status for Great Britain in its trade with the United States. U.S. acquiescence to British maritime policy regarding France. Repayment of prewar debt of private citizens in the United States to Great Britain. Next, students should read the following documents, excerpted on pages 23-28 of the Text Document: James Madison to Unknown, August 23, 1795: http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/mjmtext:@FIELD(DOCID+@lit(jm060034)) 6 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= Article from Columbian Centinel, July 15, 1795: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1605 Legislative Acts or Legal Proceedings, July 29, 1795: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1608 Anniversary of American Independence, July 8, 1795: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1606 After completing the reading, students will draft a list of reasons to support and a list of reasons against the Jay Treaty using the chart found on page 29 of the Text Document. Discussion should follow in order to create a list on which the whole class can agree. Next, students should divide into pairs in which each group must prepare a political cartoon that is either supportive or critical of the Jay Treaty. Students should follow the directions found on the bottom of page 29 of the Text Document. Each group will share their cartoon with the class when finished. VIII. Assessment Both the written record of the silent debate, the letter to the editor from activity #2, the political cartoon from activity #3 might be graded as forms of assessment. Students could also be asked to write a 500 word essay in response to the following: Why did neutrality become such a problematic issue for the U.S. during the 1790s? Use specific sources to justify your answer. VIII. Extending the Lesson Another option to better understand the complexities of the Jay Treaty would be to study the following diplomatic documents from the site of the John Jay Papers at Columbia University, accessible via the EDSITEment-reviewed site of the National Archives and Records Administration (http://www.archives.gov/education/index.html). In this activity, one student might play the role of John Jay and the other the role of the British Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger. Student should read the selected documents to better understand the important issues leading to the treaty. John Jay to Congress, 5/8/1786 http://wwwapp.cc.columbia.edu/ldpd/app/jay/item?mode=item&key=columbia.jay.04567 John Adams to John Jay, 7/19/1785 http://wwwapp.cc.columbia.edu/ldpd/app/jay/item?mode=item&key=columbia.jay.11846 Alexander Hamilton to John Jay, 5/6/1794 http://wwwapp.cc.columbia.edu/ldpd/app/jay/item?mode=item&key=columbia.jay.10765 John Jay to Lord Grenville, 8/6/1794 http://wwwapp.cc.columbia.edu/ldpd/app/jay/item?mode=item&key=columbia.jay.03991 John Jay to Lord Grenville, 8/30/1794 http://wwwapp.cc.columbia.edu/ldpd/app/jay/item?mode=item&key=columbia.jay.08531 7 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= John Jay to Edmund Randolph, 9/13/1794 http://wwwapp.cc.columbia.edu/ldpd/app/jay/item?mode=item&key=columbia.jay.04312 Students could discuss these documents and create a list of issues that their country wants resolved through negotiations. Items could include: United States: Great Britain should vacate forts along the American frontier. Negotiate the return of stolen slaves to southern owners. Cessation of attack on American merchants trading in the West Indies. End of impressments of American sailors. Establish compensation for seized ships. End of British incitement of Native Americans. Great Britain: Negotiate payment of American debt. Guarantee of American embargo against France. Granting of most favored nation status. Firmly establish U.S.-Canadian border. Next, students will flip a coin to decide which country they will represent. Then after looking at each others orders, decide upon a possible compromise or resolution to the disagreement. Students could then create their own treaty from their findings. A great follow up activity would be to write a compare and contrast essay that details how their group’s treaty was similar to and different from the original Jay Treaty (http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/diplomacy/britain/jay.htm). Another lesson possibility could be to have students read the Pacificus-Helvidius Debate of 1793, which is available at Teaching American History (http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=429). This is a useful source for understanding the first major debate in the young republic concerning the nature of the president’s power over foreign policy. It also illustrates well the growing split between Federalists and Jeffersonians, both in Washington’s cabinet and in the country at large. Finally, a great site for research into the early history of the U.S. navy can be found at the site of the Mariners’ Museum (http://www.mariner.org/usnavy/), accessible via the EDSITEmentreviewed Internet Public Library (http://www.ipl.org). Students could use this site to conduct research into the size of our early navy, the types of ships, as well as the key individuals who advocated the creation of a strong navy. IX. Selected EDSITEment Websites Teaching American History: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org President Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality (1793): http://www.teachingamericanhistory.com/library/index.asp?document=622) Editorial in The Gazette of the United States (March 13, 1794): http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1728 8 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= Editorial in The Gazette of the United States (1794): http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1732 Editorial in the Columbian Centinel (January 4, 1794): http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1731 Letter to the Editor of the Boston Gazzette (1794): http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1732 Editorial in the Virginia Chronicle (March 29, 1794) (Second Document at site): http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1732 Article from Columbian Centinel, July 15, 1795: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1605 Legislative Acts or Legal Proceedings, July 29, 1795: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1608 Anniversary of American Independence, July 8, 1795: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1606 Avalon Project at Yale Law School: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon The Jay Treaty: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/diplomacy/britain/jay.htm American Memory Project: http://memory.loc.gov James Madison to Unknown, August 23, 1795: http://memory.loc.gov/cgibin/query/r?ammem/mjmtext:@FIELD(DOCID+@lit(jm060034)) Internet Public Library: http://www.ipl.org The Mariners’ Museum: http://www.mariner.org/usnavy/ X. Additional Information Grade levels (9-12) Subject areas o U.S. History - Colonial America and the New Nation Time required (3-5 classroom periods) Skills o analyzing primary source documents o interpreting written information o making inferences and drawing conclusions o role playing Standards Alignment o People, Places, and Environments o Individuals, groups, and institutions o Power, authority, and governance o Global connections o Civic Ideals and Practices Lesson Writers o Kris Ray, Ashland University o Tucker Bacquet, Lexington High School. Lexington, Ohio Related EDSITEment Lesson Plans 9 The United States and the Problem of Neutrality, 1793-1800 — http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id= o President Madison's 1812 War Message http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=570 o The American War for Independence http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=682 o The Monroe Doctrine: Origin and Early American Foreign Policy http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=574 10