Document

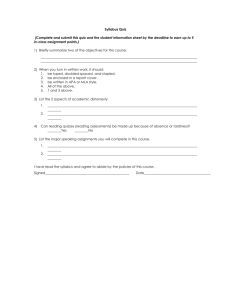

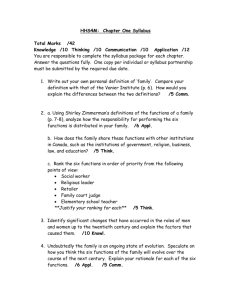

advertisement

Suppose you wanted to get to know a tract of country. The worst way to do it would be to jump into a car, drive straight from one end to the other, then turn your back on it and walk away. Yet that is what many teachers do with complex subjects, and that is why their pupils seem stupider than they really are . . . How much better would they learn the country if, before setting out, they were briefed and given maps to study; if they were rested and reoriented once or twice during the trip; and if they were shown photographs of the best spots and taken once more over the map when they reached the end of their journey? (Highet, 1950, pp. 79-80) Source: J. Lowman, (1990). Mastering the Techniques of Teaching, p. 146 Designing a course involves much more than "jumping into the text" and driving from the first chapter to the end of the book. Unfortunately, most college professors have received little or no instruction in the art and science of course design. A few are fortunate enough to have colleagues who will explain their philosophy and approach to course planning and even share entire notebooks of course objectives, lecture outlines, and learning activities. However, even equipped with these resources, all professors at the start of every new course are faced with the challenge of structuring their material to maximize student learning. Considerations must be given to the needs of the current students, the teaching style of the professor, the nature of the course content, the parameters of the college academic calendar, and many other varying constraints. One of the keys to bringing order out of this chaotic challenge is to give careful thought to the design of the course syllabus. According to Richard Pregent, "The course syllabus is a planning tool . . . in which you try to record and synchronize the content and activities of the entire course" (Pregent, 1994, p. 116). In addition, points out Barbara Gross Davis, "A detailed course syllabus, handed out on the first day of class, gives students an immediate sense of what the course will cover, what work is expected of them, and how their performance will be evaluated" (Davis, 1993, p. 14). It’s a map, a guidebook, a working contract between the professor and student. Instructional Objective of This Module Given the instructional resources contained in this module, the faculty member will be able to list and define the key components of a course syllabus and design a syllabus which reflects these components. The materials contained in this training module are basically threefold. First, there are chapters taken from excellent books on the subject of course syllabus design in higher education. Second, there are several journal articles which continue the discussion of the chapters from varying perspectives. Third, there is an assignment section which will provide you with the opportunity to implement the ideas you have gleaned from the reading in the chapters and articles. Offering suggestions for how to design a course syllabus is not intended to restrict your academic freedom and the unique expression of your approach to teaching. However, it is hoped that the material contained in the following pages will free you up from getting bogged down in the details of figuring out a workable syllabus structure so that you have creative energy left over to explore the "outer limits" of your discipline! Chapter Readings 1) J. Lowman (1984). "Planning Course Content to Maximize Interest." Ch. 7 in Mastering the Techniques of Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc., Publishers. 2) W. J. McKeachie (1986). "Countdown for Course Preparation." Ch. 2 in Teaching Tips. Lexington, MA: D. C. Heath and Company. 3) R. Pregent (1994). "Detailed Course Planning." Ch. 6 in Charting your Course. Madison, WI: Magna Publications, Inc. 4) B. G. Davis (1993). "Preparing or Revising a Course," and "The Course Syllabus." Chps. 1 & 2 in Tools for Teaching. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Publishers. These chapters do an excellent job of detailing the basics of designing a course syllabus. They are excerpted from several foundational texts in the field of college teaching procedures. Not only will these chapters walk you through the steps of structuring a clear and coherent syllabus, they also place syllabus design within the larger framework of overall course planning. Article Readings 1) R. R. Behnke & P. Miller (1989). "Information in Class Syllabus May Build Student Interest." Educator, 44, pp. 45-47. 2) M. F. Smith & N. Y. Razzouk (1993). "Improving Classroom Communication: The Case of the Course Syllabus." Journal of Education for Business, 68, pp. 215221. 3) K. Matejka & L. B. Kurke (1994). "Designing A Great Syllabus." College Teaching, 42, pp. 115-117. 4) S. F. Hockensmith (1988). "The Syllabus as a Teaching Tool." The Educational Forum, 52, pp. 339-351. Articles Used in Assignment Section Which Follows: 1) T. Clearly (1990). "Getting Ready: Checklist of Questions for the Teacher." The Teaching Professor, 4, pp. 3-5. 2) K. T. Brinko (1991). "Visioning Your Course: Questions to Ask as You Design Your Course." The Teaching Professor, 5, pp. 3-4. 3) H. B. Altman & W. E. Cashin (1992). "Writing a Syllabus." Center for Faculty Evaluation & Development, Idea Paper #27. These articles are a continuation of the material covered in the book chapter section on course syllabus design. Although much of the material overlaps in terms of the basic syllabus components, you will find in each article at least one or two new insights that will expand your appreciation for the role of the syllabus and the variations which can be explored. Your Assignment PART ONE: Evaluation of a Current Syllabus Evaluate one of your current syllabi. As you work through the checklists in the resource list above, make a list of 7-10 items you need to delete, add, or rework in order to strengthen your syllabus. PART TWO: Redesign of a Current Syllabus Using Idea Paper #27, "Writing a Syllabus," as an outline guide (see above), rework the syllabus you evaluated in Part One. Make sure you have covered the major content areas as well as taking into consideration the areas you targeted for change as a result of your evaluation.