Writing about Film

advertisement

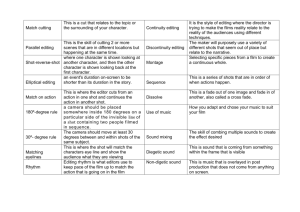

Writing about Film F r o m http://www.dartmouth.edu/~writing/materials/student/humanities/film.shtml THE CHALLENGES OF WR ITING ABOUT FILM What's so hard about writing about film? After all, we all "know" movies. Most of us could recite the plot of Independence Day with greater ease than we could recite the Declaration of Independence. We know more about the characters who perished on Cameron's Titanic than we know about many of the people who inhabit our own lives. But it's precisely our familiarity with film that presents us with our greatest writing challenge. Film is so familiar and so prevalent in our lives that we are often lulled into passive viewing (at worst) or into simple entertainment (at best). As a result, certain aspects of a film are often "invisible." Caught up in the entertainment, we sometimes don't "see" the camera work, composition, editing, lighting, and sound. Nor do we "see" the production struggles that accompany every film - including the script's many rewrites, the drama of getting the project financed, the casting challenges, and so on. However, when your film professors ask you to write about film, it's precisely those "invisible" aspects that they want you to see. Pay attention to the way the camera moves. Note the composition (the light, shadow, and arrangement of things) within the frame. Think about how the film was edited. In short, consider the elements that make up the film. How do they function, separately and together? Also think about the film in the context when it was made, how, and by whom. In breaking down the film into its constituent parts, you'll be able to analyze what you see. As you analyze and write about film, remember that you aren't writing a review. Reviews are generally subjective: they explore an individual's response to a film and so do not require research, analysis, and so on. As a result, reviews are often both simplistic (thumbs up, thumbs down) and "clever" (employing the pun-driven or sensational turns of phrase of popular magazines). While reviews can be useful and even entertaining pieces of prose, they generally don't qualify as "academic writing." We aren't saying that your individual and subjective responses to a film are useless. In fact, they can be most informative. Being terrified when you watch The Blair Witch Project can be the first step on the way to a strong analysis. Interrogate your terror. Why are you scared? What elements of the film contribute to your terror? How does the film play with the horror and documentary genres in order to evoke a fear that is fresh and convincing? And so on. KINDS OF FILM PAPERS Film Studies is a broad and fascinating field. The variety of its scholarship reflects that. Below are some of the kinds of papers you might be asked to write in a Film Studies course: Formal Analysis A formal analysis of a film or films requires that the viewer breaks the film down into its component parts and discusses how those parts contribute to the whole. Formal analysis can be understood as taking apart a tractor in a field: you lay out the parts, try to understand the function and purpose of each one, and then put the parts back together. In order to do a convincing formal analysis, you'll need to be familiar with certain key terms (outlined for you in the glossary). Returning to the tractor analogy: it's helpful to be able to understand and to use terms like "carburetor" when you take a tractor apart especially if you hope to explain your process to an onlooker. For a more complete discussion concerning how to write an analytical paper, see What is an Academic Paper?. Film History All films are deeply involved in history: they reflect history, influence history, have history. A film like Gone With the Wind not only tells a story of the South during the Civil War, but (more importantly) it reflects the values and ideas of the culture that produced it, and so can be understood as an historical document. All films are part of our culture's history. They derive from and contribute to historical events. War films, for example, take their substance from historical events. They also influence those events - by influencing wartime audiences to rally behind the troops, or to protest them. But films also have their own histories: 1. All films have production histories, which involve the details of how and why and when they were made. Production problems often (if not always) affect what we see on the screen. 2. All films have distribution and release histories: some films are released to different generations of audiences, to wildly different responses; other films are banned because they threaten certain cultural values. (Thailand, for example, banned both The King and I and the recent Anna and the King because, in the estimation of the Thais, the films were disrespectful to their royalty). 3. Finally, all films should be understood in the larger context of film history. A particular film might "make" history, through its innovations, or it might reflect certain historical trends. Ideological Papers Even films that are made to entertain promote some set of beliefs. Sometimes these beliefs are clearly political, even propagandistic: Eisenstein'sPotempkin, for example, is a glorification of Soviet values. Other films are not overtly political, but they still promote certain values: Mary Poppins, for example, argues for the idea that fathers need to take a more active interest in their families. It's important to remember, when watching a film, that even films whose purpose it is to entertain may be promoting or even manipulating our feelings about a certain set of values. Independence Day, for example, is entertaining, in part, because it plays on our feelings of American superiority and "never say die." An analysis of the film benefits from a consideration of these values, and how they are presented in the film. Cultural Studies / National Cinemas Films reflect the cultures and nations in which they were produced. Hollywood films, one might argue, reflect certain things about our nation's culture: our love of distraction, our attraction to adrenaline and testosterone, our need for good to triumph over evil, and our belief that things work out in the end. Other cultures and nations have different values and so produce different sorts of films. Sometimes these films baffle us. We might watch a French film, for example, and wonder why it's funny. Or we might watch a Russian film and wonder why the director never calls for a close up. These observations are in fact excellent starting places. Consider differences. Find out if these differences reflect something about the national character, or if they reflect trends in the national cinema. You may find that you have something interesting to say. Discussion of the Auteur Auteur criticism understands a film as the product of a single person and his vision. In most cases, this person is the director. Auteur criticism is useful because it helps us to understand, for example, what makes a certain film a "Spielberg" film. However, auteur criticism is often based on the erroneous assumption that films are like novels - that is, that one person retains authorship and control. Film is a collaborative medium. It's important to understand that no one person can control the product. The Director of Photography, the screen writers (often many), the wardrobe and make-up people, the head of the studio - all these and others have a hand in determining the final product of film. Still, auteur criticism is widely practiced and is useful in helping us to understand the common themes and aesthetic decisions in films by the same director (or producer, or star). Keep in mind, however, that the best of the auteur criticism draws on other sources, like film history or formal analysis, in order to insure that the paper is not simply an examination of the private life or the psychology of the auteur. PREWRITING STRATEGIE S Before you can write about a film you must, of course, view the film. Accordingly, the best prewriting strategy you can have is to be a careful and observant viewer. However, when viewing a film we don't always have time to study particular images and cameria techniques. This problem is less significant if we have access to videos, which permit us to review a scene again and again. Still, you'll sometimes be asked to write about a film that you'll see only once. How can you prepare yourself so that your observations will be sharp? What knowledge can you bring to a film that will inspire a thoughtful and focused analysis? THE ELEMENTS OF COMP OSITION Film is an incredibly complex medium. Just take a look at the credits at the end of any film. Each of the people listed there has contributed something essential to the film's production - from lighting, to sound, to wardrobe, to editing, to special effects. Because there's so much to talk about, you'll have to be selective if you want to write a good, focused essay. If you are a novice to writing about film, take the time to familiarize yourself with the film terms listed in the attached glossary. Knowing the terms sometimes helps you to see them on the screen. You'll begin to "see" the difference between a cutaway and a jump cut, or between a dissolve and a fade. Make sure you have a working understanding of how all the major components of film - writing, acting, lighting, composition, editing, sound, and so on - work together to create what you see on the screen. Then, when sitting down to watch a particular film, choose from among these many elements one or two that interest you. Is the editing particularly effective? Focus on that and don't struggle to take note of the lighting. Do you find the director's use of jump cuts innovative? Watch closely when these cuts occur. Perhaps the director has used jump cuts consistently whenever characters are engaged in intimate conversations. What is he trying to convey through this technique? If you are entirely unfamiliar with a film and aren't sure what you should be looking for, ask your professor. She should be able to point you to those scenes or techniques that deserve special attention. Annotating Shot Sequences Whenever you prepare to write a paper, you take notes. However, when analyzing a film, you may want to take a very particular sort of notes in which you annotate a shot sequence or scene. Annotating a scene involves labeling each shot in a sequence. For example, a scene may begin with an establishing shot, which segues into a dolly shot. The dolly shot comes to rest in a medium shot of the main character, who is looking off frame. Next comes a reverse angle subjective close-up shot, which dissolves into a montage. Labeling each of these shots - preferably using a system of abbreviations for efficiency's sake - enables you to keep track of the complex sequence of shots. When you review your annotations, you might see a pattern of camera movement and editing decisions (or, on the other hand, some unusual variation in the pattern) that better helps you to understand 1) how the director crafted his film, and 2) why the film has a certain effect on the audience. Think Beyond the Frame So far, we've been advising you to consider the formal aspects of a film's composition. However, as we pointed out earlier, you can write about film in several ways. Sometimes you will want to "think beyond the frame," and to consider questions about how the film was made, its historical context, and so on. For example, ask yourself: Who made the film? Find out who directed the film, and what other films this director made. If you've seen some of these other films, you'll have a better understanding of the themes and genres that the director is interested in. What is the production history of the film? See if you can find out anything about the conditions under which the film was made. Apocalypse Now,for example, has an interesting production history, in terms of its financing, casting, writing, and so on. Knowing something about the film's production can help you to understand some of the aesthetic and cinematic choices that the director has made. What do the critics and scholars say? Reading what others have said about the film before you see it may help you to focus your observations. If a film is particularly well known for the editing of a certain scene (the shower scene in Hitchcock's Psycho, for example), you'll want to pay close attention to the editing when you view the film. What can you learn from the film's genre? Before you see the film, think a bit about the norms and limitations of its genre. When you view the film, you can then consider how these limitations are obeyed or stretched. For example, Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven is a western that challenges its genre's typical notions of good guy vs. bad guy. Knowing how this dynamic plays itself out in other westerns helps you to understand and to appreciate Eastwood's accomplishment. Does the film reflect an interesting cultural phenomenon? Sometimes a professor will ask you to watch certain films because he wants you to examine a cultural phenomenon - for example, the phenomenon of stardom. Accordingly, you might watch The Scarlet Letter with the idea of viewing it as a "star vehicle," contributing to Demi Moore's star persona. Note that this sort of paper may also be a discussion of formal analysis: for example, you might discuss how Demi Moore was lit in certain scenes to emphasize her position as Hollywood star. RESEARCH TIPS The most important research tip that we can offer you here is: don't rely on the Internet. While the Internet can provide some interesting information about film, it generally doesn't provide you with the thoughtful analysis that will be useful to you in your work. It's best, then, to take a trip to the library and to get your hands on books and journals. WRITING TIPS In many ways, writing a paper about film is no different from writing other kinds of papers in the Humanities. You need to focus your topic, write a goodthesis sentence, settle on a structure, write clear and coherent paragraphs, and tend to matters of grammar and style. In some other ways, however, writing a paper about film has some challenges of its own. We've collected a few tips here: Don't simply summarize the film. Your professors have seen the film; you don't need to recount the plot to them. They are looking for analysis, not summary. Don't simply summarize the use of camera angles or editing techniques. You've annotated shot sequences in order to find something to say about them. Don't simply transcribe your annotation and call it a paper. Rather, posit something about what the director is trying to achieve, or the effect that this shot sequence has upon the audience. Don't limit yourself to a discussion of plot and characters. Some students come to film criticism trying to employ the techniques they've used to analyze novels in their English classes. They focus on analyzing the characters, themes, and plot. Film Studies papers focus on different elements of composition, as discussed above. Avoid the "I." It's too easy to slip into a subjective "reviewer's" stance when you use the "I" in your criticism. Try to find a more objective way of beginning your sentences than "I found" or "I feel." CITING SOURCES As in any discipline, it's essential to cite any sources that you use. Film critics cite sources using the citation method of the MLA (Modern Language Association). If you have questions about how to cite films, or how to create your Works Cited page, visit the Sources Web site. GLOSSARY OF FILM TER MS* A Accelerated Motion: Representing a shot as taking place at a higher speed than it did in reality. Also known as Fast Motion. Aspect Ratio: The height-to-width ratio of the projected screen image. B Back Lighting: Lighting which comes from directly behind the subject, placing it in silhouette. C Camera Angle: The position of the camera in relation to the subject determines the camera angle. High angle means that the camera is looking down at the subject. Low angle means that the camera is looking up at the subject. CinemaScope: 20th Century Fox's trade name for their widescreen process, which uses a ratio of 1:2.35. The term is commonly used to refer to similar widescreen processes. Cinema Verite: A way of filming real-life scenes without elaborate equipment, playing down the technical means of production (script, special lighting, etc.) and emphasizing the "reality" of the screen world. Close-Up: A shot in which a face or object fills the frame. Close-ups might be achieved by setting the camera close to the subject or by using a long focal-length lens. Composition: The arrangement of all the elements within the screen image to achieve a balance of light, mass, shadow, color, and movement. Continuity Editing: A style of editing that maintains a continuous and seemingly uninterrupted flow of action. Crane Shot: A moving shot taken on a specially constructed crane, usually from a high perspective. Cross-Cutting: Jumping back and forth between two or more locations, inviting us to find a relationship between two or more events. Cut: 1. Noun: A transition made by editing two pieces of film together. 2. Verb: To edit a film by selecting shots and splicing them together. Cutaway: In continuity editing, a shot that does not include any part of the preceding shot and that bridges a jump in time or other break in the continuous flow of action. D Day for Night: Simulating night through use of filters and under-exposure. Decelerated Motion: Representing a shot as taking place at a slower speed than it did in reality. Also known as Slow Motion. Deep Focus: A technique in which objects in the foreground and the distant background appear in equally sharp focus. Depth of Field: Distance between the nearest and furthest points at which the screen image is in reasonably sharp focus. Dissolve: Editing technique in which one shot is gradually merged into the next by the superimposition of a fade-out or fade-in. Dolly Shot: A shot taken while the camera is in motion. Dub: To record dialogue or sound to match action in shots already filmed. Dutch Tilt: A wildly tilted image, in which the subject appears on the diagonal or off-balance. E Edit: The splicing together of separate shots. Establishing Shot: A shot showing the location of the scene or the arrangement of the characters. Often the opening shot of a sequence. Extreme Long Shot: A shot notable because of the extreme distance between camera and subject. Eye-Level Shot: A shot taken at the height of normal vision. F Fade: An optical event used as a transition, in which the image on screen gradually goes to black (fade-out) or emerges from black (fade-in). Fast Motion: See Accelerated Motion. Flat Lighting: The distribution of light within the image so that bright and dark tones are not highly contrasted. Flashback: A shot or sequence that takes the action of the story into the past. Flash-Forward: A shot or sequence that takes the action of the story into the future. Form Cut: A cut from one scene to the next on the basis of a similar geometrical, textural, or other compositional value. Frame: 1. Noun: One single picture on a piece of motion picture film. 2. Noun: The boundaries of the screen image. 3. Verb: To compose a shot to include, exclude, or emphasize certain elements. Freeze-Frame: An optical effect in which the action appears to come to a dead stop, achieved by printing a single frame many times in succession. G Glass Shot: A shot in which part of the background is painted or photographed in miniature on a glass lid and placed in front of the camera so as to blend in with the rest of the image. H Hand-Held Shot: A shot made with the camera held in hand, not on a tripod or other stabilizing fixture. High-Angle Shot: See Camera Angle. High-Key Lighting: Distributing light within the image so that the bright tones predominate. I Iris: A decorative transition in which the image seems to disappear within a growing or diminishing circle. Commonly used in silent films. J Jump Cut: A cut that jumps forward within a single action, creating a sense of discontinuity. L Long Shot: A shot taken with the camera at a distance from its subject. M Mask Shot: A shot in which a portion of the image is blocked off by means of a matte over the lens, altering the shape of the frame. Medium Close-Up: A shot taken with the camera at a slight distance from the subject. In relation to an actor, "medium close-up" usually refers to a shot of the head, neck, and shoulders. Medium Long Shot: A shot taken with the camera at a distance from the subject, but closer than a long shot. Medium Shot: A shot taken with the camera at a mid-range point from the subject. In relation to an actor, "medium shot" usually refers to a shot from the waist or knees, up. Mise-en-Scene: A term used in the theater to refer to the staging of a scene, in relation to the setting, the arrangement of the actors, the lighting, etc. In film, the term is used to describe the arrangement of elements within the frame of a single shot. Montage: 1. French: The joining together or splicing of shots or sequences - in a word, editing. 2. American: A rapid succession of shots assembled, usually by means of super-impositions and/or dissolves, to convey a visual effect, such as the passing of time. 3. Russian: The foundation of film art. "The building up of film from separate strips of raw material," or "An imagist transformation of the dialectical principles, montage as the collision of ideas and cinematographic conflicts." (Quoting Pudovkin and Eisenstein, respectively.) M.O.S.: "Mit Out Sound." These initials are written on the clapboard and are briefly filmed at the beginning of a shot to designate shooting without synchronous sound recording. O Opticals: Any device carried out by the film laboratory and requiring the use of an optical printer. Dissolves, fades, and wipes fall under this category. P Panning Shot: A shot in which the camera remains in place but moves horizontally on its axis so that the subject is constantly re-framed. Parallel Shot: When two pieces of action are presented alternately, to suggest that they occur simultaneously. Process Shot: See Rear Projection. R Reaction Shot: A shot of a person reacting to the main action as a listener or spectator. Rear Projection: A trick shot in which the subject is filmed against a background that is itself a motion picture screen. Upon this screen another image - either moving or still - has been projected as a backdrop. Also known as a process shot. Reverse-Angle Shot: A shot taken by a camera positioned opposite from where the previous shot was taken. S Score: Music composed for a film. Set: An artificially constructed environment in which action is photographed. Slow Motion: See Decelerated Motion. Soft Focus: A strategy whereby all objects appear soft because none are perfectly in focus. Used for romantic effect. Sound Track: 1. 2. A recording of the sound portion of a film. A narrow band along one side of a print of film in which sound is recorded. Split Screen: The division of the projected film frame into two or more sections, each containing a separate image. Stock Shot: A shot taken from a library of film footage, usually of famous people, places, or events. Subjective Shot: A shot that represents the point of view of a character. Often a reverse angle shot, preceded by a shot of the character as he or she glances off-screen. Superimposition: A shot in which one ore more images are printed on top of one another. Swish Pan: A shot in which the camera pans so rapidly that the image is blurred. T Telephoto Shot: A shot in which a camera lens of longer-than-normal focal length is used so that the depth of the projected image appears compressed. Three-Shot: A shot encompassing three actors. Tilt Shot: A shot in which the camera remains in place but moves vertically on its access so that the subject is continually re-framed. Titles: Credits. In silent film, "titles" include the written commentary and dialogue spliced within the action. Tracking Shot: A shot in which the camera moves parallel to its moving subject. Travelling Shot: A shot taken from a moving object, such as a car or boat. Two-Shot: A shot encompassing two actors, often in close-up. V W Voice-Over: Commentary by an unseen character or narrator. Wide-Angle Shot: A shot in which a camera lens of shorter-than-normal focal length is employed so that the depth of the projected image seems protracted. Widescreen: Any aspect ratio wider than the 1:1.33 ration which dominated sound film before the 1950s and the introduction of CinemaScope, Techniscope, VistaVision, Panavision, and so on. Wipe: A transition from one shot to another in which one shot replaces another, horizontally or vertically. Z Zoom: The simulation of camera movement toward or away from the subject by means of a lens of variable focal length. * THIS GLOSSARY WAS ADAPTED FROM MATERIALS DISTRIBUTED TO FILM STUDENTS BY THE FILM DEPARTMENT AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA.