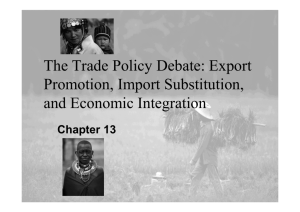

Effects of Export Promotion and Import Substitution on Poverty

advertisement

Effects of “Export Promotion” and “Import Substitution” on Poverty, Inequality and

Growth in India: An analysis in "closed loop" Input-Output framework

DEBDAS BANDYOPADHYAY

DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS

UNIVERSITY OF KALYANI

KALYANI 741235

WEST BENGAL

INDIA

Effects of Export Promotion and Import Substitution on Poverty, Inequality and

Growth in India: An analysis in "closed loop" Input-Output framework

DEBDAS BANDYOPADHYAY

DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS

UNIVERSITY OF KALYANI

KALYANI 741235

WEST BENGAL

INDIA

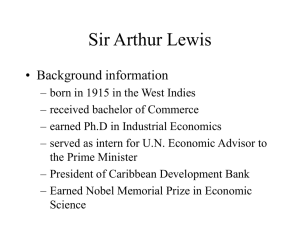

1.Introduction

Choice between export promotion and import substitution

as two competing strategies of economic development has been subject matter

of discussion among policy makers. For a developing country, this choice is

crucial as each of them affect i)foreign exchange reserve, considered to be

one of the most important factors limiting growth, and ii)income distribution and poverty through their influence on the level and structure of output and prices. It is often suggested that for developing countries promotion of labour intensive manufacturing exports is a good strategy for reducing poverty1. Import substitution, on the other hand, is generally discouraged on the ground that most of substitution has been capital intensive

in nature and contributed relatively little towards reducing poverty and

income inequality. It has also been argued that, scope of import substitution being rather limited in agriculture where most of the poor earn their

income, capital intensive import substitution will worsen the relative position of the poor in the economy. It has been emphasised that countries

pursuing industrialisation through import substitution policy may have unfavourable impact on distribution of income distribution and poverty2.

Comparison between export promotion and import substitution strategies of development should ideally be done in a framework

that captures interrelationships among income distribution, poverty and

growth. Foreign trade affects growth and income distribution through their

impact on level and structure of output and prices. Income distribution

affects poverty and growth of an economy because import content of the

consumption goods of the poor being less than that of the rich, any redi1

For example, Ranis (1973), with reference to experience in Far- East countries, calls it a conventional wisdom

to export labour intensive manufacturing goods for reducing unemployment and poverty in labour surplus

developing countries.

2

See, for example, Krueger(1970), Kervis(1973) etc.

3

stribution in favour of the poor will ease foreign exchange constraint of

the economy and enhance growth. A number of studies estimate the effects of

income redistribution on poverty, growth and other macroeconomic variables

using a framework that captures one-way dependence of growth and poverty on

income redistribution (see, Pyatt(1972),Paukert, Skolka and Maton(1974),

Sinha et al(1979),Mohammed (1981)etc among others.)3. In this framework it

is assumed that hypothetical redistribution of household income neither

affects nor affected by distribution of personal income within each industry4. Consequently, the alternative level and structure of output leaves

the overall inequality in household income distribution unaltered although

it changes the level of average income in different fractile groups of households. This is mainly because household income distribution in this methodology is not derived from personal income generated within each industry.

These studies also ignore important factors like prices, inequality in wage

structure, food grain output constraints etc. that have profound effects on

income distribution, poverty and growth of a developing economy like India5.

In this paper we estimate and compare, for Indian economy,

the effects of export promotion and import substitution strategies of

economic development on poverty, income inequality, growth and other important macroeconomic variables using a model that captures two-way dependence

between

growth and income distribution. The model focuses on i) differ-

ential access to employment due to difference in skill characteristics

tics among socio-economic groups and resultant inequality in wage earning,

ii) different rules of price and output determination in food grain and

non-food grain sectors arising out of their different supply conditions6 and

iii) differential consumption and savings behaviour across income groups in

the economy. Moreover, the model endogenously determines the "poverty group" and their level and share of income as a function of level and structure of output and prices given the distribution of income between wage

3

Mohammed (1981), however, surpassed the scope of this model by using it for studying the impact of foreign

trade on income distribution. Thus although he assumes that "trade by bringing about higher level of employment

may reduce income inequality" (Mohammed (1981), pp132) , income distribution parameters are kept fixed

under alternative export-promotion and import substitution schemes. Export promotion and import substitution

strategies may, however, increase income inequality as shown in this paper.

4

A certain mapping between implicit personal income distribution and exogenous household distribution of

income under alternative hypothetical redistribution is assumed to exist, although it is not specified.

5

Tendulkar(1971) , the first “closed loop” model for Indian economy , considered both wage and non-wage

income while closing the model with respect to consumption . He, however, did not consider distribution of

wage earning as the paper was not concerned with redistributive exercises.

6

This basic dichotomy in output and price behaviour in underdeveloped countries is clearly spelt out in Robinson

and Eatwell(1974,pp145-157). Its empirical justification for Indian economy can be found in Chakrabarty(1970),

Maity(1975) among others.,

4

and profit and distribution of wage earning. These factors, which have important bearing on the level and share of income of the poor, have not been

formally combined together, to the best of our knowledge, in a model for

analysing and comparing the effects of ‘inward’ and ‘outward’ looking

foreign trade policies on income distribution, poverty, and growth of Indian economy.

Structural specification of the model is given in section 2.

Section 3 describes the database of the study. Empirical results obtained

by simulating the model with different export promotion and import substitution polices are analysed in section 4. Major conclusions emerging from

the study and limitations of the model used are listed in the final section.

2.The Model

The primary objective of the model is to consider the interdependence of output, price and income distribution in an economy for determining poverty, inequality and growth in a segmented economy. This interdependence can be best examined by segmenting the economy in to a number of

productive sectors and the population into a number of socio-economic groups.

Economy has a number of productive sectors of which the first sector, called food grain sector, uses Cobb-Douglas type production function while the production in rest of the sectors, called non-food grain

sectors, are characterised by Leontief technology. These sectors, which are

interdependent and differ in supply conditions, play an important role in

determining the prices and output economy. We assume that, in the ‘short

run’, food grain output is supply constrained and there are excess capacities in non-food grain sectors of the economy.

Population is divided in two groups viz. "poor" or "target

group" and "non-poor" or "non-target group"7. The two socio-economic groups

are linked with different productive sectors through income and consumption. The target group is linked with productive sectors through employment" and their income consists of only "wage" income8. The non-target group,

on the other hand, is linked with productive sectors via employment as well

7

Throughout the paper we shall use the terms ‘poor’ and ‘target group’ interchangeably.

5

as ownership of assets. Thus income of non-target group consists of wage

and profit income. These groups are also implicitly linked with each other

through commodity trade. Change in the level and pattern of consumption of

one group will change the level and share of income of the other group via

its impact on the level and structure of output and prices of the economy.

Impact of trade policies on poverty and other economic variables in our

model are transmitted mainly through these linkages. Given this segmentation of the economy and its linkages, the model determines level and share

of income of the poor, the level and structure of output, prices and growth

of the economy. Model Equations are grouped into a number of blocks viz.

Income Distribution and Poverty, Output and Employment, Prices, Private

Consumption, Import, and Investment and Growth. Unknown variables in a

Block are solved taking variables determined in other Blocks as given. The

model equations, given in Table-1, form a system of interdependent parts,

each part dealing with a particular aspect of the overall problem9.

2.1.1 Income Distribution and Poverty

Poverty group consist of households with per capita income

is less than or equal to the minimum per capita income (k0) required to meet

the poverty line aggregate consumption10. We assume poverty group households i) earn their income only through employment either as hired labour or

as self employed ii) have a common dependency ratio (db ) which is a constant (z* ) multiple of the overall dependency ratio of the economy11 and iii)

net savings

of the poverty group is zero. Under these assumptions, minimum

per capita income, k0 ,is the cost of poverty line consumption times the

dependency ratio of the poverty group (see eq.1 in Table-1). Given the sectoral output and price (determined in the next section), aggregate income

of the poor(Yb), determined from distribution of sectoral employment (Li)

over different wage classes as given by wage distribution matrix (eik),is

the total wage income up to k0 (eq.2). Number of persons in the target group

is equal to the target group employment (i.e. total employment up to wage

class ko) times dependency ratio (db). Poverty ratio () and per capita inc-

The employment for the “poor’ include employment both as hired labour and self-employment.

Correspondingly the term "wage" include contractual wage payment as well as earning from self -employment.

9

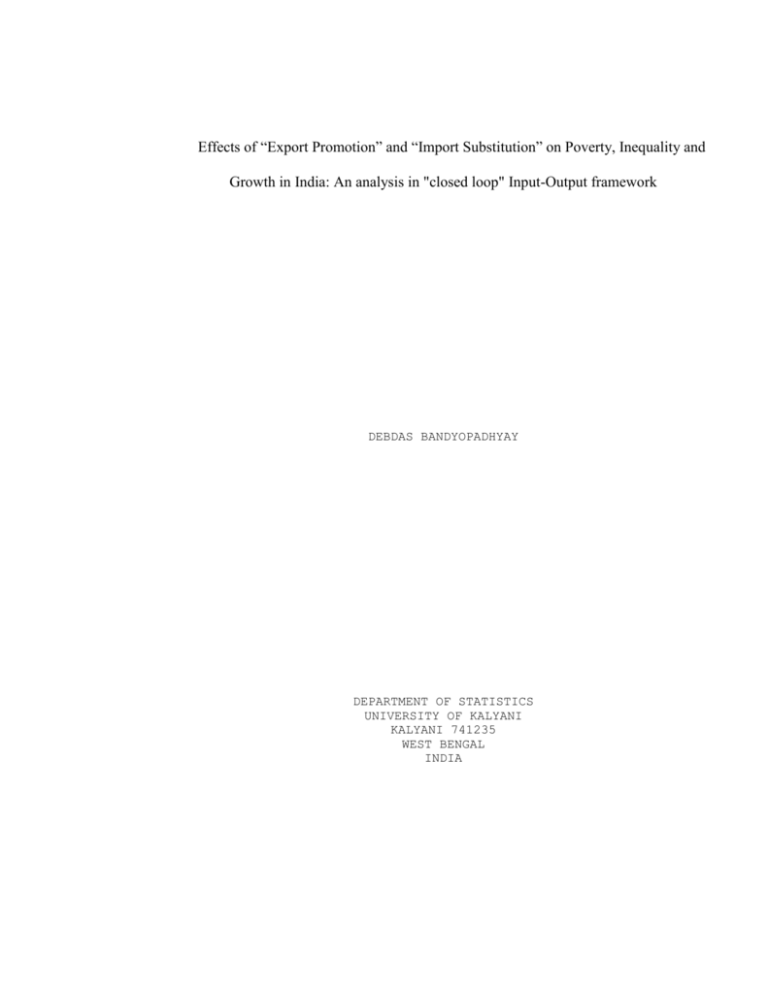

A schematic presentation of the working of the model is given in Fig.1.

10

This income definition only ensures the ability of the poor to buy the poverty line aggregate consumption but

may not guarantee poverty line normative consumption. For one possible treatment of the problem see Panda(

1992).

11

Over all dependency ratio of the economy has been defined as the number of persons , including the earner ,

per earning member of a household and is equal to total population (P *) divided by total employment (Li ).

8

6

Model Equations

Income Distribution and

(1)

k d . p .

0

b

cb

(3)

Y

d

b

b

Investment and Growth

0

k0

n

( 2)

poverty :

( 22)

eik. Li . wk

n

z*.( P*. / Li)

U

j

( 23)

/( . P*)

( 24)

I

i

j

1} /

(5)

y

y

( 6)

y e .L .w y

b

n

a

s

i 1 k

y

k

1

0

j

, j 1,2 n

25)

xi

(x

, i 1,2,3,.......n

j

x ) , i 1,2,3,.....n

R {v jc / v 0jc} , j 1 , 2 , 3 n

R

v /v

i

i

0

i

j

f

0

26)

j

j

j

Employment

D. p

(a b) / c

1

n

w

a / c

1

.p

b / c

f

x a .x C I

(9)

ij

j 1

a

Output and

1

k

(1 t d ). y /(1 ). P*

a

x

i

ik

n

b .U

i 1 k 1

(8)

j

i 1

(4) d b .( eik. Li . wk ) / P*

(7 )

.v

j

j

k0

n

b

j

j

. v {(1 R j)

i 1 k 1

1

d

ij

j 1

j

i

. xi G i

*

i

E M

, i 2,3, n

*

i

i

L a .x . p / w

L . x , i 2,3, n

(10)

1

(11)

1

i

i

1

1

i

Pr ice

(12)

(13)

(14)

(15)

p . x ( p , p , w ) x ( p , p ) 0

p (1 ).(1 t ).( m l ) , j 2,3,...n

1s

1

1

j

m

l

j

1

f

j

j

n

j

n

j

n

d

ij

i 1

i

i

s

a . e . w

1

a . p .(1 t ) a p

j

1d

j

jk

k 1

kj

i 1

m

ij

mi

(1 t mi)

, j 2,3,.....n

j 2,3,.......n

Demand :

Consumption :

(16)

(17)

(18)

(19)

( 20)

C y /P

C (1 s ) y / P

P .P

P (1 ). P

1

1

b

2

h

1

*

2

C

i

2

a

*

[

2

P {a . p

m

m

i

m 1

m

i

n

bi .(C a j .

m

m

j 1

p

j

)}] ,

i 1,2,3...n

Im port

21)

M

i

n

a .x

j 1

m

ij

j

hi (C i

I

Gi )

*

i

, i 1,2,3,....n

Dependency ratio of the poverty group is then a constant (z*) multiple of over all dependency ratio of the

economy. ( see eq.3).

7

Table-2

Notations

(Superscript ‘0’ refer to base year, superscript ‘m’ to population group ‘m’ and subscript ‘i’ to sector ‘i’)

A. Endogenous Variables

Percentage of poor

PCE for population group ‘m’

Agg. Private Consumption for sector ‘i’

Dependency ratio

Investment by sector of origin

Normative wage rate

Sector ‘i’ employment

Sector ‘i’ unit labour cost

Producer’s price for sector ‘i’ output

Size of population group ‘m’

CPI for poor

Unit material cost for sector ‘i’

Capacity growth rate of value added

Aggregate value-added growth rate

Investment by destination

Value-added for sector ‘i’

Sector ‘i’ output

Market supply of sector ‘1’ output

Change –in- stock

Aggregate income of the non-poor

Aggregate income of the poor

Per capita income of the non-poor

Per capita income for the poor yb

B. Parameters

Domestic and imported input coefficients aijd , aijm

Capital coefficient

bij

Parameters of LES for population mth gr. aim , bim

Parameters of agricultural production fn.

D,b,c

(i,k)th element of emp. distribution

e ik

Labour-output ratio for sector 'i'

i

Average import content of domestic demand hi

Li

Stock-flow conversion factor for sector ‘i’

i

li

pi

Sector 'i' investment fn. parameters

i , i i , i

P m Savings rate for the non-poor

sh

p m Direct tax rate

td

mi Indirect tax rate

ti

R i Mark-up for sector 'i'

i

R Import duty

tmi

Ui

Average wage rate in kth wage class

wk

Vi

Average wage rate in sector 'i'

wi

xi

Market demand sector ‘1’( base yr. price) x1d

x is

C. Exogenous Variables

x Export of sector ‘i’ output

Ei *

ya

Government consumption of sector ‘i’

Ci *

yb Population

P*

ya

cm

Ci

db

Ii

k0

ome of the poor (Yb ) are then determined in eqns.4&5. Aggregate income of

the non-target group (Ya) consists of wage income above k0 and profit income

(Yf) from which their per capita income (Ya) is determined eqs.6& 7).

2.1.2 Output, Price and Employment

Food grain output is determined from farmers' supply response

function taken as a function of food grain price(p1),average wage rate in

food grain sector (w1),and fertiliser price (pf)(eq.8)12. Its price is market

clearing type and is determined from eq.12 such that excess supply in the

food grain market (right hand expression of eqn.12) is zero. Non-food grain

sectors’ output are demand determined and obtained from input- output material balance equation (eqn.9) and their prices are determined by Kaleckian

type mark up pricing rule (eqn.13). Unit material cost(mj) and wage cost

12

Food grain supply response function depends upon many other variables. We, however, ignore such variables

and absorb their effects via the constant ‘D’. Further, fertiliser price, pf , in the supply response function is

obtained by applying indirect tax rate on the producers’ price as determined in the eq.13.

8

SCHEMATIC DIAGRAM OF THE WORKING OF THE MODEL

Wage rate &

WDM

PL

Income of poor & non-poor

% of people below PL

Domestic & Imported

Input-Output coeffs.

Supply Response Fn.

for AG

Output for AG

Sectoral

labor coeffs.

oe

Mkt supply

for AG

Prices of NAG

( I-O Model )

Sectoral mark up &

tax rates

Wage rate

& WDM

Sectoral private cons.

Prices for

AG

Pvt. cons. demand

for AG

LES

parameters

Sectoral

prices

Market demand for

AG

Sectoral Exports

Changein -stock

Imports

Output of

NAG

( I-O Model )

Sectoral gross Inv.

Sectoral Govt.

cons.

Sectoral Output

Output of AG

Sectoral Inv Functions

Fig.-1

Endogenous

Exogenous

AG : Agricultural goods, NAG : Non-agricultural goods, WDM : wage distribution matrix ,PL:

Poverty line

(lj) are blown up by mark up rate (j )and indirect tax rate(tj) to get the

sect-oral market price (eq.13)13. Material unit cost consists of domestic

and imported material input cost while wage cost depends upon labour coefficient(j) and distribution of sectoral employment over different wage classes (eqns.14&15). Employment in food grain sector is determined by factor

demand equation obtained from the first order condition of constrained profit maximisation problem in agriculture (eqn.10.). Employment in non-food

grain sectors are obtained by applying labour output ratio to sectoral output (eq.11).

13

Market supply for food grain, x1s (=x1 (p1, pf, w1) - a11.x1 ), is defined as food grain output net of food grain

inputs. Food grain producers own consumption are bought from market.

9

2.1.3 Demand

Demand for private consumption, investment, change-in-stock

and importare endogenously determined while Government consumption and exports are exogenous. Per Capita Consumption Expenditure (PCE) for the two

groups of population, C1 and C2, are determined from their respective per

capita income, Yb and Ya(eqns.16&17). Sectoral breakdown of PCE for the two

groups of population obtained through LES for the respective groups are

combined to arrive at private consumption vector for the entire population

(eqs. 18,19&20). Finally imports for intermediate and final use are determined in eq.21 using input-output import coefficient matrix (amij) and import coefficient of final demand hj. Investment and change-in-stock are related to output in eqns.22, 23 and 24. Investment requirement by sector of

destination (Uj), consists of replacement investment, net fixed investment

and an intercept term. Replacement investment is taken as a fixed proportion of sectoral value-added. Net investment is obtained through multisectoral version of accelerator principle (eq.21). If j is the investmentoutput gestation lag in sector j then net investment in sector 'j' is a

function of increase in value-added during gestation period. Assuming uniform distribution of investment over gestation period, net investment in

sector j is given by the last term of eq.21 where j is incremental capital

value-added ratio and Rj is the post base year value-added growth rate (eqn.

25). Thus sectoral investment in our model is demand driven. Investment by

origin for sector ‘i’ is determined from using capital coefficient matrix

(bij) (eq.22). Change-in-stock is obtained by applying stock-flow conversion

factor to output change (eqn.24). Finally aggregate growth rate is determined by eqn.25.

3.Data Base

The model is applied to twenty two sector Indian economy for

the year 1996-97(referred as Base Year)14. Operation of the model requires

point estimates of different technological, behavioural and policy parameers. Estimates of the parameters relating to consumption and investment functions, coefficients relating to material and labour inputs, imports, change in stock and the sectoral tax rates are taken from Eighth Plan Technical Note, Planning Commission(1995),Government of India (hereafter referred

10

as Tech. Note). Estimates of sectoral mark-up rates and policy parameters

like direct tax rate, household savings rate and corporate tax rate are taken from relevant issues of National Accounts Statistics and Annual Survey

of Industries, Government of India. All India poverty line (0) has been estimated from the estimates of rural and urban poverty line as given in Tech. Note under the assumption of lognormality of all India PCE (See Appendix A)15.

Initial estimate of sectoral employment distribution matrix,

taken from Labour Bureau (1973), National Council of Applied Economic Research (1975) and Roy (1979), is first corrected for changes in CPI for agricultural and industrial workers during intervening period and then made consistent to base year i)Mean monthly private consumption of people below

poverty line and their percentage and ii) sectoral total wage by an iterative method16

Estimates of parameters of food grain supply response function are taken from Kawagoe et al.(1985)(estimate 4). Intercept term(D) of

the supply function is so determined that food grain output obtained from

this function is same as that of the base year.

The point estimates are made consistent to base year structure of the economy so that given these point estimates and the exogenous

variables the model reproduces the observed base year structure the economy17. Base year values of the variables as reproduced by the model, referred as Basic Solution, are taken as historically given benchmark values

with which the changes under different policy scenarios are compared18.

Selected macroeconomic indicators under Basic Solution are presented in

Table-3

4. Empirical Analysis

Effects of foreign trade policies on poverty, inequality and other

macroeconomic variables may be studied by analyzing the quantitative impact

14

See Appendix for mapping of Tech. Note sector classification into our classification.

All India Poverty Line estimated is Rs .201 at 1996-97 prices.

16

See, Bandyopadhyay(1986) ,for details.

17

Different problems arise in the construction of consistent data base of an economy. See Taylor (1985),

Bandyopadhyay (1986) for details.

18

Units of goods are so chosen that sectoral prices are unity at the base year when the economy is assumed to be

at equilibrium. Also to maintain scale comparability, estimated changes under different policy scenario over the

Basic Solution are expressed per Rs. one million.

15

11

of volume and structure of different export promotion and import substitution schemes. In our model any change in volume and structure of export

and import disturbs the base year equilibrium of the economy and sets on a

chain reaction operating through changes in output, price, income distribution and poverty in the economy. The equilibrium is restored when aggregate savings equates with aggregate investment through changes in output,

prices income distribution, and poverty19.

Table-3

Selected Macroeconomic Indicators for Indian Economy, 1996-97

as reproduced by the Model+

Economic Indicator

Estimate Economic Indicator

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

579087

494345

95096

159169

102287

112641

21.03

22.09

4.40

GDP

Private Consumption

Government Consumption@

Gross Investment

Export@

Import

Savings Rate(%)

Investment Rate (%)

Aggregate Growth

(Post 1996-97)

10. Per capita Income*

a) Poor

b) Non-poor

159.20

553.40

11.Per capita Cons8.

a) Poor

b) Non-poor

12. Poverty

a)Ratio(%)

b)Sen’s Index

13. Inequality(L.R.)

a) Income

b) Consumption

c) Wage

14.Dependency Ratio

a)Target Group

b) Overall

Estimate

159.29

482.15

26.34

15.24

0.259

0.225

0.347

4.13

4.89

@ Exogenous + Rs. Crores at 1991-92 prices * Rs. at 1991-92 prices

4.1 Effects of changes in level and structure of export.

Effects of volume and structure of exports are studied under

six alternatives as described in Table-4. While the first two alternatives

study the impact of change in volume of export in absence and presence of

food grain supply constraints in the economy the rest mainly analyze impact

of changes in structure of exports20. Macroeconomic impact of alternative

volume and structure of exports are given in Table-5. It is found that 10

percent increase in volume of exports, keeping the structure same as in the

19

Schematic diagram showing working of the model and an iterative procedure for its solution are given in the

Appendix..

20

For this we have divided the exporting sectors into two groups viz. traditional exports consisting of sectors like

agricultural food products, mining and textiles and non-traditional exports consisting of manufacturing sectors.

Their impacts are studied both in presence and absence of constraints in the food grain sector of the economy.

12

base year, increases private consumption, employment and growth respectively by 1.28, 1.32 and 1.40 percent when there is no food grain output constraint in the economy. However, in presence of food grain output constraint,

this favorable impact of increase in exports is much reduced as can be seen

from the results under alternatives 1 and 2. Increase in volume of ex-ports

also pushes up aggregate savings rate of by 1.30 per cent and pushes down

the rate of foreign savings by 2.00 per cent.

Table 4: Description of Alternative Export Promotion Schemes.

Case No.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Description of alternative cases.

Base year exports increased by 10 percent.

Case No.1 with food grain output fixed at

Basic Solution level.

10 per cent increase in traditional exports

Case No.3 with agricultural output fixed at

Basic Solution level.

10 percent increase in non-traditional exports.

Case 5 with food grain output fixed at Basic

solution level.

Analysis of impact of pattern of export, considered under

alternatives 3,4,5 and 6, show that export promotion of traditional sectors

have more favorable impact on private consumption, employment and growth

than that of non-traditional exports. This is because an increase in traditional export(Case no. 3)increase, consumption and growth by

0.49, 0.28

and 0.54 percents respectively. The corresponding increase non-traditional

exports are 0.32, 0.20 and 0.49 percents respectively. Moreover, it is seen

that increase in traditional export in presence of food grain output constraint has more detrimental effect on the economy than that of non-traditional export.

Effects of increase in volume and pattern of export on economic

condition of poor and non-poor are given in Table-6. Results show that

monthly per capita income and consumption of both poor and non-poor increases due to increase in volume of export but increase for the non-poor is

much higher than that of the poor. Thus we see that 10 percent increase in

export results in 1.55 per cent increase in income of the non-poor, the co-

13

rresponding increase for the poor being 1.00 per cent. (see case 1.). Moreover, even this positive impact on poor vanishes and the income of the poor

falls by 34 per cent in presence of food grain output constraint in the economy (see case 2.). This is because export promotion in presence of output

constraint causes demand pull increase in food grain prices which, in turn

results in overall price rise in the economy hurting the poor. Economic position of the non-poor, however, slightly improves (income of the non-poor

increases by 1.72 per cent) as a part of profit due to price rise accrues

Table 5: Change in Macroeconomic aggregates under

alternative Export Promotion Schemes21.

Case

No.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5

6.

Agg.

Growth

101.43

101.03

100.54

100.34

100.49

100.44

Private

Cons.

101.28

100.99

100.49

100.11

100.32

100.26

Employment

101.32

100.95

100.28

100.18

100.20

100.16

Savings

Ratio

Import

CPI

101.31

100.89

100.56

100.28

100.50

100.42

101.64

101.03

100.72

100.68

100.97

100.94

101.04

101.93

100.97

100.32

100.01

101.63

to the non-poor. Consequently, distribution of real income shifts against

the poor.22

Analysis of impact of pattern of export reveals that favor-able impact of

increase in traditional export is more than that of non- traditional export. Comparison of alternatives 3 and 5 show that 10 per cent increase in

traditional export increases the income of the poor and non poor by 0.25

and .06 per cent respectively. Comparison of alternatives 4 and 6, however,

show that expansion of traditional export in face of food grain output constraint hurts the poor more than the non-poor. Percentage of ‘poor’ and

Sen’s index of poverty decline as a result of export promotion, provided

there is no food grain output constraint in the economy (see Table-6). Thus

10 percent increase in volume of export reduces the percentage of poor by

1.21 percent and Sen’s index by 0.71 percent. However if there is food grain output constraint in the economy both the percentage of poor and Sen’s

index increase by 1.47 percent and 0.92 percent respectively due to 10.0

percent in volume of exports. Further, it may be seen that expansion of traditional export has more favorable impact on poverty than that of the nontraditional export. This is mainly because traditional exports originate

21

22

Expressed as percentage change, per Rs. million , over the Basic Solution level.

Note that increase in CPI for poor under case 3. is 1.14 per cent and the same for the non-poor is 1.08 per cent.

14

from such sectors which are more labor intensive and whose share of income

among poor than the industries from which non-traditional exports originate. However expansion of both traditional and non- traditional export

increase poverty in presence of food grain output constraint. Results on

impact of inequality due to increase in volume and changes in pattern of

export show export promotion accentuates income inequality. Thus we see

that 10 percent increase in export results in 0.92 and 0.57 percent of

income and consumption inequality. Further it is seen that inequality

Table 6: Change in Economic Profile of Target and Non-Target Group under

Alternative Export Promotion Schemes

Case

No.

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

Per capita income

Poor

Non-poor

100.95

100.12

100.25

99.70

100.06

99.91

101.55

101.72

100.85

101.22

100.98

100.15

Poverty Index

H. C.

Sen’s

98.79

99.01

99.01

101.34

99.24

99.88

99.29

100.01

99.68

100.40

99.75

100.32

Inequality(L.R)

Income Consumption

100.92

102.73

101.65

100.32

100.19

100.25

100.57

102.56

100.17

100.13

100.18

100.18

accentuating effect of non traditional export is more than that of traditional export.

4.2: Effects of changes in volume and structure of Import

Substitution.

In order to study the effect of import substitution we consider import

substitution in both intermediate as well as final use. Further, to compare

how structure of import substitution affect poverty, income inequality and

growth we consider the major import using sectors viz. petroleum, metal

products, machine tools and fertiliser industries. Different import

substitution schemes considered for analysis are given in Table-7.

Macroeconomic impacts of alternative import substitution schemes are given in Table-8. It is seen that 10 percent import substitution

in all sectors (Case no.1) increase consumption, employment and growth by

0.84, 0.94 and 0.98 percent respectively. Aggregate import requirement fall

by 4.76 percent whereas aggregate savings rate increase by 2.67 percent.

Thus we see that import substitution, in general, have favorable impact on

consumption, employment and growth, but this positive impact is much less

15

than that of corresponding increase in export. Comparison of results under

Cases 1 and 2, however, show presence of food grain output constraint in

the economy further reduces this positive impact. Comparison of results under Cases 4,5,6show varying macro economic impact of sectoral import substitution. Thus it is seen that import substitution in Petroleum sector has

maximum positive impact on consumption, employment and growth than the corresponding level of import substitution in other sectors of the economy.

Table 7: Description of Alternative Import Substitution Schemes.

Case No.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Description of Alternative Cases.

10 percent import substitution

Sectors.

Case 1 with output of sector 1

Solution level

10 percent import substitution

Sector

10 percent import substitution

in all importing

fixed at Basic

in Machine tools

in Petroleum Sector.

10 percent import substitution in Fertilizer sector

Sector.

10 percent import substitution in Electronics and

Communications.

Economic impact of import substitution, both overall as

well as sect-oral, on the poor and non-poor are presented in Table-9. It is

seen that due to 10 percent import substitution across the sectors, income

of the poor and non-poor increase respectively by 0.32 and 1.00 per cent.

Thus positive impact of import substitution on the income of the poor is

much less (almost one-third) than that of the non-poor. Moreover, comparison of results under Cases 1 and 2 show that the discriminatory effect of

import substitution on income of poor and non-poor increases in presence of

food grain output constraint in the economy. At the sectoral level, it is

seen that import substitution in Petroleum and communications sector has

comparatively larger positive impact on income of the poor than the other

sectors of the economy. This favourable impact of import substitution is,

however, much less than that of export promotion. Further, it may be seen

import substitution reduces poverty provided there is no food grain output

constraint in the economy. Finally, it is interesting to note that increase

in inequality due to import substitution is more than that of export promotion.

16

4.7 Growth-equity trade-off under “export promotion” and

“ Import substitution”: A Comparison

In recent years there have been a number of studies on the

link between poverty, inequality and growth23. Kuznets(1955) was first to

observe from cross country data that process of development has a tendency

to be accompanied by increase in inequality which was subsequently confirmed by Oshima(1962),Adelman and Morris(1973),Adelman(1974),Chenery and Syrquinn(1975) etc.

Recent empirical evidences, however, are far from unamb-

iguous24. In this section we compare “export promotion” and “import substitution” strategies of development in terms of growth-equity trade-off exhibited by them25.

Table 8: Change in Macroeconomic aggregates under

alternative Import substitution Schemes.

Case

No.

Agg.

growth

Private

Cons.

Employment

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

100.98

100.36

100.14

100.85

100.44

100.61

100.84

100.20

100.12

100.69

100.35

100.10

100.94

100.29

100.20

100.97

100.46

100.16

Savings

Ratio

102.76

102.98

100.79

101.31

100.89

100.82

Import

95.24

90.61

99.74

100.68

100.97

101.82

CPI

101.24

101.78

100.92

100.92

100.01

100.36

Following Ahluwalia(1974), we combine per capita consumption

level of poor and non-poor in to a single utility index using semilogarithmic Social Welfare Function. Per Capita Utility (PCU) under different “export promotion” and “import substitution” schemes and their percent change

over Basic Solution PCU, calculated under ‘equal weight’ and ‘poverty weight’ social welfare function, are given in Table- 1026.

It is seen that bo-

th “export promotion” and “import substitution’ show moderate growth-equity

trade–off under ‘equal weight’ SWF, its magnitude being lees for “export

promotion” than “import substitution”. However, under ‘poverty weight’ SWF,

magnitude of this trade-off is substantial for both strategies. It is also

23

See, Tendulkar and Jain(1955) , Deininger and Square(2000) among others.

For example, Mohammed(1981), Tendulkar and Jain(1995) and Deininger and Square(2000) found little

support for the so called “Kuznets hypothesis”.

25

A policy is said to exhibit unambiguous growth-equity trade-off if a positive growth effect of the policy is

accompanied with a decline in Per Capita Utility ( PCU) under both “equal weight” and “poverty weight” SWF

and vice-versa.

26

See Appendix , for details.

24

17

seen that growth-equity trade-off is more for traditional than non-traditional export and it increases when there is food grain output constraint in

the economy.

Table 9: Change in Economic Profile of Target and Non-target Groups

under Alternative Import Substitution Schemes.

Case

No.

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

Per capita income

Poor

Non poor

100.32

99.96

100.11

100.14

100.13

100.09

100.99

101.19

100.45

100.69

100.57

100.40

Poverty Index

H. C.

Sen’s

99.39

101.21

99.95

99.43

99.68

99.97

99.60

101.86

99.85

100.00

99.80

99.94

Inequality(L.R)

Income Consumption

101.07

101.69

100.16

100.35

100.32

100.48

101.02

101.92

100.15

100.29

100.27

100.34

5. Conclusions and Limitations

The paper estimates and compares the effects of “outward looking”(export promotion) and “inward looking” (import substitution) strategies of economic development on income distribution, poverty and growth

for Indian economy using a model that captures two way dependence between

growth and income distribution. Factors typically found in a developing country like India viz. “fix-flex” mode of output and price determination,

high wage inequality in wage earning and food grain output constraint. Endogenous determination of income distribution, poverty and growth considering the mentioned above factors is the novelty of our model which, to the

best of our knowledge, have so far not been used for analysing Indian trade

policies. Simulation of the model with different “export promotion’ and

‘import substitution” policies show i) export promotion, particularly for

traditional sectors, reduces poverty provided there is no food grain output

constraint in the economy, ii) poverty reducing effect of export promotion

is substantially more than that of import substitution, iii) both export

promotion and import substitution increases inequality, particularly when

there is food grain output constraint in the economy, but inequality accentuating effect of import substitution is

more than that of export prom-

otion and iv) both export promotion and import substitution exhibit growthequity trade-off but its magnitude is substantial and more for import substitution than that of export promotion particularly under the “poverty

weight” SWF. Thus our findings indicate that economic development through

export promotion is more effective than import substitution for “growth

18

with poverty reduction” provided there is no food grain output constraint

in the economy and one is ready to accept social cost due to higher level

of economic inequality.

Before concluding it is, however, necessary to point out some of the

important limitations of our study some of which may have substantial implications for ‘long run’ interpretations of our findings. First use of input output technology in non-agricultural sectors of the economy rules out

substitution possibilities among inputs in response to price changes under

Table-10:Percentage change in Per capita Utility Level

alternative Export Promotion and Import Substitution Schemes27.

Case

No.

Per capita utility (PCU)

(Export Promotion)

Per capita utility (PCU)

(Import Substitution)

Equal Weight Poverty Weight Equal Weight

1)

2)

3)

4)

5)

6)

100.66

100.70

100.45

100.55

100.70

100.72

101.61

101.72

101.05

101.30

102.50

102.78

100.82

100.98

101.36

101.22

101.52

101.62

Poverty Weight

102.50

102.87

101.61

101.32

101.14

101.96

different policy scenario. Secondly use of LES for estimating private consumption demand has well known limitations in capturing demand changes over

a long period. Thirdly endogenous determination of investment on the basis

of accelerator type relation ignores the direct effects of variables like

profit rate, price tax etc on investment28. Fourthly modelling of supply

response on for the food sector as a whole using only three explanatory

variables is restrictive. Finally distributional effects of trade policies

on choice of technology which may have considerable impact on poverty and

growth is not considered in the present study.

Basic Solution PCU level under “equal weight” and “poverty weight” SWF are 1.13 and 2.56 respectively.

In so far as investment in our model is demand driven, indirect effects of these variables on investment are

captured through demand.

27

28

19

APPENDIX

A: Determination of All India Poverty Line.

Let the all India poverty line to be estimated be x. Also let Fr and

Fu be distribution functions of per capita consumption expenditure in rural

and urban India. Then proportion of total expenditure, pj, having per capita

expend-iture xj or less is given by

p

j

[ Pr . F r ( x j ) Pu . F u ( x j )] /( Pr Pu ) (1)

where Pr and Pu are rural and urban populations. Now,if Fr and Fu are twopara-meter lognormal distribution functions with parameters (xr ,r) and (xu

,u) then

p

j

p .( y

r

jr

)

p .( y

u

ju

) (2)

where,

y (1 / ). log( x / x ) / 2(3)

y (1 / ). log( x / x ) / 2(4)

p P /( P P ), p P /( P P )(5)

jr

r

ju

u

r

r

j

r

j

r

r

u

u

u

u

u

r

u

and (.) is standard normal C.D.F. Now, let Qj be the aggregate share of

per capita consumption up to xj for the country as a whole, then

Q

j

x

[ p . j x.d F r ( x)

p . x d F ( x)] /( P.x )(6)

[ p x .( y ) p . x .( y )] / P.x (7)

r

r

j

u

0

r

r

rj

u

0

u

u

ju

u

where x is average per capita consumption expenditure for the country as a

who-le and P is the total population. Now if we assume that all India per

capita consumption expenditure follows two-parameter log normal

distribution with parameters x and then we know the Lorentz ratio for the

per capita consumpt-ion expenditure is given by

L 2. ( / 2 ) 1 (8)

Now L can be estimated from observed distribution of per capita consumption

expenditure and one such formula based upon Simpson’s 1/3rd rule is given by

n

L 1 ( p

j 1

j

p

).(Q Q ) (9)

j 1

j

j 1

where n is the number of expenditure class limits considered. Now, an

estimate of L as determined from (9) can be used in (8) to determine

uniquely. The all India poverty line x can then be determined from the

eqs.(10) and (11).

( ) (10)

y (1 / ). log( x / x ) / 2 (11)

20

B: SOLUTION PROCEDURE FOR THE MODEL

In order to solve the Model we adopt an iterative procedure which directly follows from the logical structure of the model. We may

note that any change in policy parameter and/or exogenous variable disturbs

the model equilibrium and initiates an adjustment mechanism that works through changes in different endogenous variables in the model. The equilibrium is re established when aggregate savings equals aggregate investment.

The iterative procedure starts with some initial guess values of sectoral

output and prices and consists of the following steps:

i)

Estimate sectoral gross value added and calculate their rates of

growth(Rj )by eqn.26

ii)

Estimate sectoral employment(Li) by eqns.10 for sector 1 and by eqn.11

for i=2,3,...n.

iii)

Estimate per capita income and consumption of the ‘poor’ and ‘nonpoor’ (Yb, Ya ,C1, C2) by eqns. 5,7,16,17 after determining K0 ,db ,yb

and ya by eqns.1,3,4,2 and 6 respectively.

iv)

Estimate sectoral private consumption (Ci ) by eqn.20

v)

Estimate investment by origin ( Ui ) as well as destination(Ii) and

change in stock(Si) by eqns.22,23 and 24

vi)

Estimate terminal year sectoral import(Mi) by eqn.24

vii)

Estimate sectoral output(Xi) by eqns.8 for i=1 (or replace it by

exogenously given output if there is supply constraint) and by eqn.9

for i=2,..n.

viii)

Repeat step i) through vii) until the output vector converges. Then

proceed to step ix).

ix)

Using this output vector estimate sector 1 prices (pj) by eqn.12 and

use it for determining prices for rest of the sectors by eqn.13.

x)

Repeat step ix) till price vector converges.

xi)

Stop iteration when successive levels of output and price vectors differ by less than a given tolerance level.

Simultaneous convergence of output and price vectors ensures

savings-investment identity. This is checked under each policy scenario to

confirm validity of the solution procedure.

C: Welfare Evaluation of Alternative Policies

Welfare evaluation of alternative policies has been done using a social welfare function of semilogarithmic type where utility is written as a function of per capita consumption of the ‘poor’ and ‘non-poor’

(See Ahluwalia(1974)). Thus if Cb and Ca denote per capita consumption of

the ‘poor’ and ‘non-poor’ then social utility function is given by,

U = N1.1

21

log Cb + N2.2 log Ca

where N1 and N2 are the number of the ‘poor’ and the ‘non-poor’ and 1 and

2are weights. Using social utility function defined above we define two

alternative measures of per capita social utility, Ue and Up from a)”equal

weights” and b) “poverty weights” form of social utility function. The

‘equal weights” social utility index can be shown to be a measure of increase in welfare if we assume that the utility function is symmetric. The

“poverty weights” social utility index, on the other hand, provides a measure of welfare improvement when weights are different for different classes. Thus

Ue

= N1.log Cb + N2.log Ca /N

Up

= N1.1. log Cb + N2.2.log Ca /N

where N is the total population29.

D: Mapping of Tech. Note Sectors into 22 Sectors

Sector Name

1. Food grain

2. Non-food grain agriculture

3. Allied Agriculture

4. Food Manufacturing

5. Coal and Lignite

6. Crude petroleum and Natural gas

7. Other minerals

8. Textiles

9. Wood and Wood products

10. Paper and Paper Products

11. Leather and Leather products

29

Tech. Note

Sector No..

1 to 4

5 to 11

12 to 14

20 to 23

15

16

17 to 19

24 to 28

29

30

31

Sector Name

12. Rubber and .Plastic products

13. Petroleum and Coal products

14. Chemical Fertilizer

15. Other chemicals

16. Metal & Metal Products

17. Machine & Machine Tools

18. Electronic Equipment

19. Transport Equipment

20. Other Manufacturing

21. Construction & Electricity

22. Services

Tech Note

Sector No.

32,33

34,35

36

37 to 39

42,43

44 to 47

48,49

50 to 52

53

54,55

56 to 60

See Ahluwalia (1974) for method of deriving weights for ‘equal weights‘ and ‘poverty weights’ form of utility indices. In our study

weights are determined in such a way that they yield ‘poverty weights’ 0.6 and 0.4 for the target and non-target groups of population.

22

REFERENCES

Adelman,I (1974): “On the state of Development Economics”, journal of

development Economics,,V.1

Adelman,I and Morris,T (1973): “ Distribution and Development”, Journal of

Development Economics,V.1

Ahluwalia, M.S.(1974): “Income Inequality: Some Dimensions of the problem”

in Chener et al (eds.),1974

Bandyopadhyay,D.(1986) : “A Multisectoral Model of Income Distribution,

Poverty and Growth : Some policy issues for Indian economy”. Ph.D. Thesis,

Indian Statistical Institute.

Chakrabarty, S.K. (1970); “The Behaviour of prices in India, 1952-1966: An

Empirical Study”, Ph.D.thesis, LSE.

Chenery, H.B. et al.(1974): “Redistribution with Growth’, Oxford University

Press.

Deininger,K.and L.Square(1998): ”New ways of looking at old issues:

inequality and growth”, Journal of Development Economics, V57

Kawagoe,T. et al.(1985): “The intercountry Agricultural Production Function

and Productivity difference among countries”, Journal of Development

Economics,V.19

Kuznets,S.(1955): “Economic growth and Income Inequality”, American

Economic Review XLV,V.1

Labour Bureau (1973): “Report on Second Occupational Wage Survey(196365):’,Ministry of Labour, Government of India.

Maity,P.(1975): ”Price, Income, Interest in a Two-Sector Model of

Agriculture and Non-agriculture: A theoretical and empirical analysis for

Indian economy”, Ph.D. Thesis, Indian Statistical Institute.

Mohammad,S.(1981): “Trade ,Growth and Income Distribution: A case study of

India” ,Journal of Development Economics,V.9

NCAER(1975): “Changes in rural income in India,1968-69,1969-70,197071”,NCAER, New Delhi.

NSSO(1965): ”Tables with notes on Rural employment and unemploymet”, NSSO,

Government of India.

Panda,M.K.(1992): “A Plan Model Incorporating Normative Minimum consumption

Targets”, Journal of Quantitative Economics, V.8, No.1

Paukert,F,skolka,J and Maton,J.(1974):”Redistribution of income,Patterns of

Consumption and Employment: A case study of phillipines”, in Polenske,K.R.

et al (eds.),Aadvances in Input-output Analysis, Ballinger,Cambridge(Mass).

Planning Commission (1995): “ A Technical Note to the Eighth Plan of

India”, Planning Commission, Government of India.

Pyatt,G. et al (1972): “ A methodology for development planning applied to

Iran”, Mimeo., Warwick, England.

Ranis,G.(1973): “The exchange constraint on development-A partial solution

to the problems: comment”, The Economic Journal,LXXXIII

Roy,B.(1979): “Distribution of income and wage differentiation in

agriculture and manufacturing industries”, Tech. Report, NIRU, ISI.

Sen,A.K.(1981): “Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and

Deprivation”, OUP, New Delhi.

Sinha, R. et al(1979): “Income Distribution, Growth and Basic Needs in

India”, Vikash Publishing House, India.

Taylor,L. (1983): “Structuralist Macroeconomics”, Basic Books, New York.

Taylor, L. and E.L. Bacha (1976): “ The Unequalising Spiral: A first Growth

Model for Belinda”, Quarterly Journal of Economics, XC(1).

Tendulkar, S. D.(1971): “Interaction between Domestic and foreign resources

in economic growth”,chapter6 in Chenery et al (eds.),”Studies in

Development planning”,Harvard University Press, Cambridge(Mass.)

Tendulkar,S.D. and L.R.Jain (1995): “ Economic Growth, Relative Inequality,

and Equity: The Case Study of India”, Asian Development review,V.13,N.2.