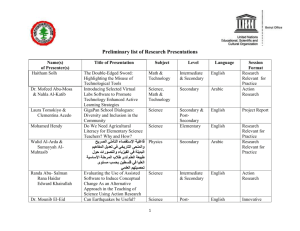

Interim Report - Higher Education Academy

advertisement