From Neutrality to War, 1921-1941

advertisement

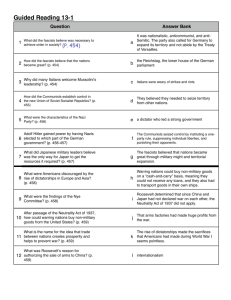

The United States and Europe: From Neutrality to War, 1921-1941 Lesson Plan #2: Legislating Neutrality, 1934-1939 I. Introduction By the early 1930s Americans became increasingly pessimistic about the ability to prevent the outbreak of wars through international cooperation. They instead turned toward measures designed to prevent the United States from intervening in any foreign war that may occur. The result was a series of neutrality laws passed in 1935, 1936, and 1937, that sought to avoid the reappearance of circumstances that most Americans believed had drawn the country into World War I—namely arms sales and loans to belligerent countries. In this lesson students will examine a series of primary source documents that will help understand why these laws were passed, and how they were applied in the mid- to late-1930s. II. Guiding Question Did the neutrality laws of the 1930s represent an effective U.S. response to world affairs? III. Learning Objectives After completing this lesson, students should be able to: Explain the “Merchants of Death” thesis and how it shaped the U.S. approach to neutrality. List the main terms of the neutrality laws passed during the 1930s. Discuss how these laws were implemented and revised in response to developments in Europe. Identify on a blank map the locations of the major events in Europe from 1935 to 1939. Assess the overall effectiveness of U.S. neutrality policy during this period. IV. Background Information for the Teacher As seen in the previous lesson [insert link to Lesson #1: The Triumph of Pacifism] during the 1920s American peace activists sought U.S. participation in international efforts to prevent the outbreak of war. The most important of these efforts were the Five-Power Treaty, which was the world’s first successful agreement for the limitation of naval armaments, and the Kellogg-Briand Pact, in which the signatories renounced war “as an instrument of national policy.” Both of these developments had been hailed by pacifists, but by the early 1930s there was a growing sense of pessimism regarding the ability of arms control and Kellogg-Briand to stop wars from breaking out. Militant nationalist regimes in Japan and Germany both announced that they would no longer be bound by prior agreements on disarmament, and in 1931 Japan invaded the Chinese province of Manchuria. As the critics of KelloggBriand had predicted, there could be no “outlawry of war” without effective enforcement. These disturbing developments led American pacifists to move away from international efforts to prevent war and toward measures designed to ensure that the United States would remain neutral in any foreign wars that might occur. In this they had the wholehearted support of American nationalists, who rejected pacifism but opposed a repeat of World War I, when the country eventually was drawn into an overseas conflict that they believed had not served any vital American interest. The public’s demand for neutrality surged in 1934 with the publication of Merchants of Death by H.C. Engelbrecht and F.C. Hanighen. This book, an examination of the international arms industry, quickly became a best-seller, but its most talked-about chapter concerned the United States from 1914 to 1917. The country had entered the war, the authors claimed, because American bankers and arms merchants had a vested interest in an Allied victory. The thesis immediately struck a chord among many Americans, including non-pacifists; after all, this was a time in which President Roosevelt was calling businessmen “economic royalists,” and accusing them of standing in the way of social justice. Given this rhetoric, it was not hard to for average Americans to believe that wealthy businessmen had pushed the country into war for their own selfish interests. A Senate committee under the leadership of North Dakota Senator Gerald Nye was established to investigate the book’s charges, and held hearings throughout 1935. While the Nye Committee never succeeded in proving that banks and munitions firms had led the country into war, it produced some eye-popping headlines about the vast profits that such concerns had made during the war. The tangible results of all this were the Neutrality Acts passed in 1935, 1936, and 1937. Collectively these laws sought to keep the United States out of foreign wars by banning the activities that Americans believed had drawn the country into war in 1917. This meant that, when a war occurred anywhere in the world, U.S. arms manufacturers would be prohibited from selling their products to any country involved in that war. Further, the Neutrality Acts barred American banks from extending loans to belligerent countries, and banned Americans from traveling on ships belonging to such nations. Finally, the 1937 act mandated that all overseas trade with countries at war—aside from arms sales, which remained illegal—had to be conducted on the basis of “cash and carry.” In other words, belligerents would have to pay for such materials in cash, and transport them in their own ships. The goal was to prevent U.S. vessels from coming under attack in any future war, simply by keeping such ships out of war zones. The Neutrality Acts were invoked and revised at several points during the 1930s in reaction to the worsening international climate. By the end of that troubled decade it seemed clear that a new world war was on the horizon, and most Americans were confident that they could stay out of it. Others, however, worried that the country’s neutrality laws could do as much harm as good. Among these was President Roosevelt, who—even though he dutifully signed each of the Neutrality Acts after Congress passed them—expressed concern that they might actually help aggressors. After all, a country that launches an attack on a neighbor might reasonably be expected to have already stockpiled all the necessary arms necessary to complete the operation. A completely impartial arms embargo, which applied to both sides in any conflict, might actually have the effect of hurting the victims of aggression, who presumably were in greater need of weaponry. This became a particular matter of concern in 1939, when war finally did break out between Nazi Germany on one hand, and Great Britain and France on the other. The question was whether a set of laws designed to apply to the international climate of 1914-1917 were appropriate to the circumstances of 1939. It was a question that many Americans would be asking in the months to follow. V. Preparing to Teach this Lesson Review the lesson plan. Locate and bookmark suggested materials and links from EDSITEment-reviewed websites used in this lesson. Download and print out selected documents and duplicate copies as necessary for student viewing. Download the Text Document for this lesson, available here as a PDF file. This file contains excerpted versions of the documents used in the various activities, as well as questions for students to answer. Print out and make an appropriate number of copies of the handouts you plan to use in class. Finally, study the interactive timeline “America on the Sidelines: The United States and World Affairs, 1931-1941 http://www.kfallon.com/civ/] that accompanies this lesson. This timeline will, through text, maps, and photographs, guide students through the major European events of 1933-1939, and will ask students for each event to identify (choosing from among a menu of options) how the Roosevelt administration responded to it. The correct choice for most of these will be “no formal action,” which should illustrate for students the extent to which the United States remained uninvolved with European affairs during this critical period. Analyzing primary sources: If your students lack experience in dealing with primary sources, you might use one or more preliminary exercises to help them develop these skills. The Learning Page at the American Memory Project of the Library of Congress (http://memory.loc.gov/learn/start/prim_sources.html#) includes a set of such activities. Another useful resource is the Digital Classroom of the National Archives, which features a set of Document Analysis Worksheets (http://www.archives.gov/digital_classroom/lessons/analysis_worksheets/worksheets.htm l). Finally, History Matters offers helpful pages on “Making Sense of Documentary Photography” (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/Photos/) and “Making Sense of Maps” (http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/maps/) which give helpful advice to teachers in getting their students to use such sources effectively. VI. Suggested Activities Activity #1: Merchants of Death? Students will begin the lesson by reading an excerpt from the deeply influential 1934 book Merchants of Death, located in its entirety at the site “Heritage of the Great War” [http://greatwar.nl/frames/default-merchants.html], which is linked from the EDSITEment-reviewed World War I Document Archive [http://www.lib.byu.edu/%7Erdh/wwi/]. The excerpt is available on pages 1-3 of the Text Document that accompanies this lesson. Students should read the excerpt as homework, and then imagine that they are average citizens in 1934. Students should write a five-paragraph letter to their congressman or senator, in which they give their reaction to what they have just read, and then suggest some means of ensuring that the United States remain neutral in any future wars. Before they begin, it may be helpful for students to review (either on their own, or together in class) what they learned about the causes of U.S. involvement in World War I. This should provide useful background to help them understand the thesis of the reading. When students have returned to class the following day, have them exchange essays with a partner and peer edit each others’ work. To conclude, ask students how this book would likely have affected Americans’ perceptions of the Great War. Activity #2: The Neutrality Acts, 1935-1937 In response to public demand generated in part by Merchants of Death, Congress in the mid-1930s passed a series neutrality laws designed to prevent U.S. involvement in another war. In this activity, students will look at these neutrality acts and determine their effectiveness. To begin, have students read the following, excerpts of which may be found on pages 5-9 of the Text Document. They are located in their entirety at the EDSITEment-reviewed resource Teaching American History [http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org], and at “WWII Resources” [http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/index.html], which is accessible via the EDSITEment-reviewed resource Digital History [http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/]. Neutrality Act of August 31, 1935: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/paw/049.html Bennett Champ Clark’s Defense of the First Neutrality Act, December 1935, "Detour Around War," Harper’s Magazine, CLXXII (December 1935), 1-9. http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1502 Excerpts from an address to the Senate by Tom Connally (D-TX), August 24, 1935 Statement by President Roosevelt, August 31, 1935: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/paw/050.html Neutrality Act of February 29, 1936: http://ibiblio.org/pha/paw/068.html Neutrality Act of May 1, 1937: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1564 To help guide their reading, students should answer the following questions, located on page 10 of the Text Document: What were the key provisions of the Neutrality Act of 1935? Why do you think they were included? Why did Bennett Champ Clark believe that the Neutrality Act was necessary? Who, according to Clark, were the chief opponents of this legislation, and why? What problem did Senator Connally and President Roosevelt see in the 1935 Neutrality Act? Why do you think Roosevelt signed it, in spite of this problem? What provisions were added by the Neutrality Act of 1936? Why do you think these were included? What provisions were added by the Neutrality Act of 1937? Why do you think these were included? Next, direct students to the interactive timeline, “America on the Sidelines: The United States and World Affairs, 1931-1931” [http://www.kfallon.com/civ/]. On this timeline, students will learn about events in Europe between 1933 and 1939, as well as how the United States reacted to them. Remind students to keep the provisions of the Neutrality Acts in mind as they go through the interactive. This will take approximately one class period to complete, so ensure adequate computer lab time. To conclude, hold a class discussion about the effectiveness of the Neutrality Acts. This issue should be considered on two different levels. On the one hand, students should be asked whether the laws had their intended effect of keeping the United States out of war during the 1930s (the obvious answer to which is “yes”). More importantly, students should be asked to consider the larger implication of the neutrality laws. How might the events of the 1930s have worked out differently if Americans had not been prohibited from selling arms or extending loans to belligerents? How likely was it that the United States might have been drawn into the Italo-Ethiopian War, the Spanish Civil War, or a war arising over the Rhineland, Austria, or the Sudetenland? Might the United States have been able to play a more productive role in European politics in the absence of the Neutrality Acts? VII. Assessment The letter that students write for Activity #1 might be graded as one means of assessment. As a concluding assessment activity, students should be asked to write an essay in response to the following question: Although President Roosevelt signed the Neutrality Act of 1935, he indicated that it “might have exactly the opposite effect from that which was intended.” In light of the actual events of 1933-1939, do you think his concern was warranted? In addition, students should be able to identify and explain the significance of the following: Merchants of Death Neutrality Acts Spanish Civil War Rhineland Sudetenland Munich Agreement Finally, students should be able to locate the following on a blank map: Ethiopia Spain Austria Czechoslovakia Poland VIII. Extending the Lesson For students who wish to learn more about United States foreign affairs during the 1930s, one could research any of the items on the interactive timeline using the links provided there. Students could then write an essay, make a poster, or design a PowerPoint presentation in which they describe the event and the U.S. response to it. The EDSITEment-reviewed site of the United States Senate [http://www.senate.gov] includes a brief narrative about the Nye Committee [http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/merchants_of_death.htm], which was formed in 1934 in response to investigate the charges made by Hanighen and Engelbrecht in Merchants of Death. Students might be asked to read this account and suggest why the Nye Committee’s activities would have helped pave the way for the Neutrality Acts. The Document Library at the EDSITEment-reviewed New Deal Network [http://newdeal.feri.org/index.htm] features an editorial entitled “Pro-Fascist Neutrality” [http://newdeal.feri.org/nation/na37144p033.htm], which appeared in the influential liberal journal The Nation in January, 1937. The editorial is useful for this lesson in that it illustrates one of the chief arguments against how the Neutrality Acts were applied— that a supposedly “impartial” arms embargo might have the practical effect of helping one side over the other. Students might read this as an adjunct to the second activity. They might further be asked whether the same logic might not be applied to other events of the 1930s, such as the Italo-Ethiopian War. On October 5, 1937, President Roosevelt gave a speech in Charlottesville, Virginia, in which he lamented the state of world affairs and suggested an international “quarantine” in order to fight an “epidemic of world lawlessness.” The speech is available in its entirety at Teaching American History (http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=956). Students might be asked to read it in light of the Neutrality Acts and consider why the speech was so controversial. IX. EDSITEment-reviewed Web Resources Used in this Lesson Digital History: http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/ WWII Resources: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/index.html Neutrality Act of August 31, 1935: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/paw/049.html Statement by President Roosevelt, August 31, 1935: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/paw/050.html Neutrality Act of February 29, 1936: http://www.ibiblio.org/pha/paw/068.html The New Deal Network: http://newdeal.feri.org/index.htm “Pro-Fascist Neutrality,” The Nation, January 1937: http://newdeal.feri.org/nation/na37144p033.htm Teaching American History: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org Bennett Champ Clark’s Defense of the First Neutrality Act, December 1935: http://www.teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=150 2 Neutrality Act of May 1, 1937: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=1564 Franklin D. Roosevelt, “Quarantine” Speech, October 5, 1937: http://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/index.asp?document=956 United States Senate: http://www.senate.gov “Merchants of Death,” September 1934: http://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/minute/merchants_of_death.h tm The World War I Document Archive: http://www.lib.byu.edu/%7Erdh/wwi/ The Heritage of the Great War, 1914-1918: http://www.greatwar.nl/ H.C. Engelbrecht and F.C. Hanighen, Merchants of Death: http://greatwar.nl/frames/default-merchants.html X. Additional Information Grade levels: 10-12 Subject Areas: U.S. History Time Required: 2-3 class periods Skills: o Analyzing and comparing first hand accounts o Debating key issues and topics o Interpreting written information o Information gathering o Making inferences and drawing conclusions o Observing and describing o Representing ideas and information orally, graphically and in writing. o Utilizing the writing process o Utilizing technology for research and study of primary source documents o Vocabulary development o Working collaboratively Standards Alignment: www.ncss.org/standards/strands/ o NCSS-2—Time, Continuity, and Change: The study of the ways human beings view themselves in and over time. o NCSS-3—People, Places and Environment: The study of people, places, and environments o NCSS-5—Individuals, Groups, and Institutions: The study of interactions among individuals, groups, and institutions. o NCSS-6—Power, Authority, and Governance: How people create and change structures of power, authority, and governance. Lesson Writers: o John Moser, Ashland University, Ashland, OH o Lori Hahn, Sheffield Middle Senior High School, Warren, PA Teacher/Student Resources: o Interactive Timeline o Text Document Related EDSITEment Lesson Plans: o American Diplomacy in World War II [http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=702] o “The Proper Application of Overwhelming Force”: The United States in World War II [http://edsitement.neh.gov/view_lesson_plan.asp?id=653] o The Road to Pearl Harbor: The United States and East Asia, 19151941