Chapter 17: Macroeconomic Goals

advertisement

Chapter 17: Macroeconomic Goals

Macroeconomic concerns

High employment

Employment and the business cycle

Business cycles

Fluctuations in real GDP around its long-term growth trend.

Expansion : A period of increasing real GDP .

Peak: The point at which real GDP reaches its highest level during an expansion.

Recession: A period of declining or abnormally low real GDP .

Trough: The point at which real GDP reaches its lowest level during a recession.

Depression: An unusually severe recession.

“Economists—and society at large—agree on three important macroeconomic goals:

rapid economic growth, full employment, and stable prices.”

What is responsible for these dramatic changes in economic well being?

Rapid economic growth….In the United States—as in most developing

economies—our output of goods and services has risen faster than the population.

As a result, the average person can consume much more today—more food,

clothing, housing, medical care, entertainment, and travel—than in the year 1900.

Topic of discussion: real GDP.

Facts presented in book: real GDP has increased dramatically over the greater

part of the century—part of the reason is an increase in population: more workers

can produce more goods and services, but Real GDP has actually risen faster

than population. During this period, while the US population did not quite triple,

the quantity of goods and services produced each year has increased more than

tenfold. Hence, the remarkable rise in the average American’s living standard.

Although output has grown, the rate of growth has varied over long periods

of time:

o 1959-1973: real GDP growth by 4.2% each year

o 1973-1991: real GDP growth slowed to 2.7% per year

o 1991-2000: growth picked up again, averaging 3.7% per year

These may seem like slight differences. But over long periods of

time, such small differences in growth rates can cause huge

differences in living standards.

Economists and government officials are very concerned when

economic growth slows down.

Growth does not benefit everyone.

Living standards will always rise more rapidly for some groups

than others. For example, since the late 1980’s, economic growth

has improved the living standards of the highly skilled, while less

skilled workers have actually become worse off. Partly, this is due

to improvements in technology that have lowered the earnings of

workers whose roles can be taken by computers and machines.

Will everyone benefit from growth, in the long run?* Some see a

role for the government in taxing successful people an providing

benefits to those left behind by growth.

High Employment

High employment—or consistently low employment—is an important

macroeconomic goal.

o Unemployment rate: percentage of the population who would like to work,

but cannot find jobs.

Unemployment rate is never zero

Employment and the Business Cycle:

When firms produce more output, they hire more workers,

when they produce less output, they tend to lay off workers.

We would thus expect real GDP and employment to be

closely related, and indeed they are. In recent years, each

1 percent drop in output has been associated with the loss

of about half a million jobs. Consistently high

employment, then, requires a high, stable level of output.

The periodic fluctuations in GDP are called the business

cycle.

When output rises, we are in the expansion phase,

which continues until we reach a peak.

Then, as output falls, we enter a recession—a

period of declining output.

When output hits bottom, we are in the trough of

the recession.

When a recession is particularly severe or

long lasting, it is called a depression.

Stable Prices: With very few exceptions, the inflation rate has been positive from 19222001.

o With very few exceptions, the inflation rate has been positive, on

average, the prices have risen each of those years.

o However, during 1979 and 1980, we had double digit inflation—

prices rose by more than 12% in both years.

During the 1990’s, the inflation rate averaged less than 3%

per year, and it has stayed low through the end of 2001.

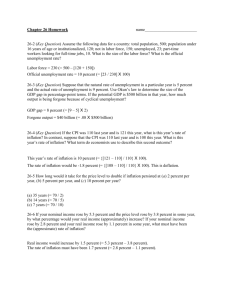

Chapter 18: Production, Income, and Employment

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the unemployment rate are important

because they describe aspects of the economy that dramatically affect each of us

individually and our society as a whole. This chapter describes what these

statistics tell us about the economy, how the government obtains them, and how

they are sometimes misused.

GDP is the total value of all final goods and services produced for the

marketplace during a given year, within the nation’s borders. Three ways to

measure GDP are the expenditure approach, the value-added approach, and

the factor payments approach. Understanding these approaches tells us much

about the structure of our economy.

Definition of GDP: the money value of all final goods and services produced in a

country over a given time period. GDP is typically measured for a country for a period

of a quarter or a year (though one could theoretically measure the GDP of California for

a month).

An intermediate good is: a good purchased for resale or for use in producing another

good; goods used in producing final goods. Purchase for resale purposes.

A final good (or service): is a good sold to its final user; goods ready to be consumed

(shelved goods are a good example of final goods)

Transfer payment: any payment that is not compensation for supplying goods and

services. Transfer payments represent money redistributed from one group of citizens

(taxpayer) to another (the poor, the unemployed, and the elderly). While transfers are

included in government budgets and spending, they are not purchases of currently

produced goods and services, and so are not included in government purchases or in

GDP. Government transfers account for 37 percent of all government spending. A

transfer payment is a payment made with no expectation of something in exchange.

o In the expenditure approach to measuring GDP, we add up the value of the

goods and services purchased by each type of final user: households,

businesses, government, and foreigners.

1. The Expenditure Approach:

This is based on the value of the goods and services sold in the economy for a given

period:

Consumption Goods and Services: purchases by households. Consumption is the

part of GDP purchased by households as final users. We traditionally use the letter

(C) to designate such expenditures.

Private Investment Goods and Services: purchases by businesses. Private investment

has three components: (1) business purchases of plant and equipment (2) new home

equipment; and (3) changes in business firms’ inventory stocks (stocks of unsold

goods). The traditional term applied to the accumulation of capital goods (including

construction), this also includes the accumulation of inventories; which, as unconsumed

goods or services, are generally viewed as accumulations of capital. We use the letter (I)

to designate such expenditures or accumulations.

Government Goods and Services: purchases by government agencies. Spending by

federal, state, and local governments on goods and services. The government makes

up a huge proportion of the total expenditures in modern American society. All public

works projects, military expenditures, and construction of public buildings contribute to

the total government participation in the demand for final goods and services (G).

Net Exports: purchased by foreigners (NX). Either negative or positive, this represents

the total quantity of goods and services we produce domestically relative to the quantity

sold abroad. If positive, we are selling more abroad than domestically, and visa versa.

The components of GDP:

GDP= c + i +g +nx

(Supply side) (Demand side)

C = Consumer spending

I = Investment

G = Government spending (federal, state, local)

NX = net export (export-import)

-If export greater than import=Trade surplus

-If import greater than export=Trade surplus

C = Consumer spending is usually 70% of a nations GDP (USA)

I = Investments usually consists of about 18% of the US GDP

G = Governmental spending usually makes up 15% of GDP

NX = The US trade deficit is -3%

Is the 3% trade deficit a big deal?

Relatively speaking, NO! How do we find out if the same is not true for another country?

We divide the “deficit” by the GDP or 300 Billion (trade deficit, United States) divided

by the GDP which is 10 Trillion dollars, and we see that is a small number considering

the whole.

On the other hand, there are countries who owe three times their GDP.

Foreign debt/GDP gives the percent of the GDP is comprised in debt.

GDP = C + I + G + NX

Net Investment = Investment – depreciation

o The GDP is NOT the sum total of all transactions in the economy. That

would be redundant. If we included every transaction for the purposes of

evaluating economic performance, we would capture a lot of transactions that

didn't reflect the real value of the product of society. As an example, the price

of the loaf of bread you buy in the supermarket would be added to the cost of

the ingredients sold to the bakery. Used car sales do not contribute to the

overall production of society. Once the original car is bought and sold, that

represents the last transaction of interest for measuring the production of the

economy.

If there were intermediary agents involved in the transaction,

the total amount of exchange could be quite considerable. The

real value of production rests in the opportunity cost of

producing the loaf of bread, but the final measure of the value

of that bread is found at the point of sale. GDP is traditionally

measured as the final value of all goods and services produced

in the economy, or the Value-Added from each component of

the productive process.

2. The Value Added Approach: GDP = Sum of Value added by all firms:

measuring GDP by summing the value added by all firms in the economy.

A firm’s value added is the revenue it receives for its output, minus the

cost of all the intermediate goods that it buys

In the value added approach, GDP is the sum of the values added by all

firms in the economy.

3. The Factor Payments Approach: In any year, the value added by a firm is

equal to the total factor payments made by that firm.

Factor payments: payments to the owners of resources that

are used in production.

= Sum of factor payments made by all firms

= Wages and salaries + interest + rent + profit

= Total household income

Households own the economy's resources (factors of production; land labor and

capital) whose services they rent or sell to firms through factor markets in exchange for

factor payments (rental payments, wage payments, interest payments, and profits).

Households use their factor income to purchase goods and services in the goods and

services markets: consumption goods and services, capital goods. They also use part of

their factor income to pay government taxes.

Real versus Nominal GDP

When a variable is measured over time with no adjustment for the dollar’s

changing value, it is called a nominal variable. When a variable is adjusted for

the dollar’s changing value it is called a real variable.

Since our economic well-being depends, in large part, on the goods and

services we can buy, it is important to translate nominal GDP, which is

measured in current dollars, to real GDP, which is measured in purchasing

power. In general, all nominal variables must be translated into real variables

to make meaningful statements about the economy.

The unemployment rate is defined as the percentage of the

labor force that is unemployed, and is calculated each month.

This measure understates unemployment because it fails to

account for involuntary part-time employment and

discouraged workers. On the other hand, it also overstates

unemployment by including as unemployed some people who

are not in the labor force. Regardless of these problems, the

unemployment rate provides valuable information about

conditions in the macroeconomy.

The Limitations of GDP

GDP is not perfect. Why?

1. It ignores non-market activities. (Mother watching children)

2. It ignores the underground economy. (Illegal market)

3. It ignores the environment. (Damage to the environment should be subtracted

from GDP).

To calculate the percentage of the economy that is illegal divide the size of the

underground economy/GDP.

Economic Well Being

GDP/population

GDP per person

Standard of Living

The size of the economy

GDP is used to guide the economy in two ways. In the short run,

changes in real GDP alert us to recessions, and give us a chance to

stabilize the economy. In the long run, changes in real GDP tell us

whether our economy is growing fast enough to raise output per capita

and our standard of living, and fast enough to generate sufficient jobs

for a growing population. Although GDP is extremely useful, it

suffers from measurement problems. It doesn’t take quality changes

into account, it can’t accurately measure underground production, and

it does not include nonmarket production. Because of these problems,

we must be careful when interpreting long-run changes in GDP.

There are four types of unemployment: frictional, seasonal, structural,

and cyclical. Our economy is at full employment when there is no cyclical

unemployment. Unemployment is costly for individuals and for our

society. The purely economic cost of unemployment can be measured as

the difference between potential GDP (the amount of GDP that can be

produced at full employment) and actual GDP. There are also broader

costs of unemployment, both to individuals (psychological and physical

effects) and to society (the unemployment burden is not shared equally

among different groups).

Types of Unemployment:

1. Frictional unemployment is that unemployment caused by information or

search costs. Usually when a person quits, is fired, or enters the labor market,

there are jobs available for which that person is qualified. The person will be

frictionally unemployed because it takes time (and effort) to find the jobs that are

available.

2. Seasonal Unemployment: Unemployment is caused by relatively regular and

predictable declines in particular industries or occupations over the course of a

year, often corresponding with the seasons. Unlike cyclical unemployment, which

could occur at any time, seasonal unemployment is an essential part of many jobs.

For example, your regular, run-of-the-mill, department store Santa Clause can

count on 11 months of unemployment each year.

Hotel and catering

Tourism

Fruit picking

3. Structural Unemployment: Structural unemployment exists when a person is not

qualified for any job because the amount he can contribute to any job (his

marginal revenue product) is less than the minimum wage payable for that job.

The minimum wage can be set legally, by union negotiations, or by the force of

public opinion. Structural unemployment can exist even if the minimum wage

was zero. Structural unemployment is associated with those that are displaced due

to changes in technology or structure of the economy. Here labor must be

restrained so their skills match the new technologies.

4. Cyclical Unemployment: is associated with downturns in the economy.

Cyclical unemployment is caused by short-term economic changes, whereas

structural unemployment covers a range of situations including a mismatch

between the skills of the labor force and the available jobs. Cyclical

unemployment is associated with an economic recession or a sharp economic

slowdown. It occurs due to a fall in the level of national output in the economy

causing firms to lay-off workers to reduce costs and protect profits.

Frictional and structural unemployment are unavoidable in a dynamic

economy. These two combined are called the Natural Rate of

Unemployment, or the full-employment rate of unemployment. The

Natural Rate of unemployment is estimated to be about 5.5%.

How unemployment is measured:

Early each month, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) of the

U.S. Department of Labor announces the total number of

employed and unemployed persons in the United States for the

previous month, along with many characteristics of such persons.

These figures, particularly the unemployment rate--which tells

you the percent of the labor force that is unemployed--receive

wide coverage in the press, on radio, and on television.

Unemployment is measured by the Bureau of Labor Statistics

(BLS).

It surveys 60,000 randomly selected households every month.

The survey is called the Current Population Survey.

Labor Force: those people who have a job or who are looking for a job.

Unemployment rate: the fraction of the labor force that is without a job.

The unemployment rate is calculated by dividing the people who want jobs but don't have

them by the labor force.

Unemployment/Labor Force = Unemployed/(Unemployed + employed)

Criticisms of the Unemployment Rate

Does not include discouraged workers: those who have given up looking for work

because they could not find a job. (understates unemployment)

Does not account for the "hidden unemployment." "Hidden" unemployment

includes those who are working part-time but wish to have a full-time job, and

those who are grossly overqualified for their positions, the underemployed.

(understates unemployment)

To be unemployed, a person must only "say" he has actively sought work.

(overstates unemployment)

The Costs of Unemployment:

Economic costs: The costs of unemployment are the goods and

services that might have been produced and consumed that are lost

forever. The costs of unemployment are generally viewed by the

society as those related to unemployment insurance and social

assistance programs for those who are able to work.

Cost of unemployment = Potential output - Actual output

Where potential output is the level of GDP the economy would attain if all

resources were fully employed. During recessions when unemployment is

high, some labor is sitting idle and that lost work can not be made up.

There are also significant, noneconomic costs of unemployment such as

individual and family stress.

Potential Output: the level of output the economy could produce if operating at

full employment.

Chapter 19: The Monetary System, Prices, and Inflation

Basic Chapter Overview/Summary:

The Monetary System: History of the dollar, Why Paper Currency is accepted as a

means of payment

Measuring the Price Level and Inflation: Index numbers, The consumer price index,

how the CPI has behaved, from index to inflation rate, how the CPI is used, real variables

and adjustment for inflation, inflation and the measurement of real GDP

The costs of inflation: the inflation myth, the redistributable cost of inflation, the

resource cost of inflation.

Using the theory: sources of bias in the CPI, the consequences of overestimating

inflation, the future of the CPI

Appendix: Calculating the consumer price index

The Monetary System:

A monetary system establishes two different types of standardization in the

economy:

1. A monetary system establishes a unit of value. A unit of value is a common unit

for measuring how much something is worth. With a standard monetary unit,

like the dollar, we can easily price individual goods and services, putting a

single price on each item instead of having to compute a different exchange price

for every different pair of commodities (e.g., 1 cup of coffee = 2 newspapers = 6

minutes of office work as a temp = 3 minutes of my teaching services).

2. A monetary system concerns the means of payment—the things we can use as

payment when we buy goods and services. Means of payment is anything

acceptable as payment for goods and services. -- you can use it to buy whatever

you want. Money makes it much easier for people to exchange the goods and

services they produce for the goods and services that they want. Money "greases

the wheels of commerce," by making it much easier for people to exchange the

goods and services they produce for the goods and services that they want.

Having a generally accepted currency eliminates the need for barter (trading

goods and services for each other), and makes the volume of transactions a lot

larger than it would otherwise be.

Also: 3. Store of value -- money has some use as an asset, because it holds its

nominal value over time and, unlike stocks or bonds, its value does not fluctuate from

day to day. Unlike stocks or bonds, there is no risk that dollars will suddenly become

worthless. In sum, money is a virtually riskless asset. It is also a very liquid

(convertible into cash; spendable) asset, which is another desirable quality.

In 1913, the Federal Reserve System was created to be the national monetary

authority in the United States. The Federal Reserve was charged with creating and

regulating the nation’s supply of money, as it continues to do today. The earliest forms

of payment were precious metals and other valuable commodities. Eventually, to make it

easier to identify the value of precious metals and they were minted into coins whose

weight values were declared on their faces. Because gold and silver coins could be

melted down into pure metal and used in other ways, they were still commodity money.

Commodity money eventually gave way to paper currency. Initially, paper currency was

just a certificate representing a certain amount of gold or silver held by a bank. But

today, paper currency is no longer backed by gold or any other physical commodity.

This type of currency is called fiat money.

Fiat money: anything that serves as a means of payment by government

declaration.

Items designated as money that are intrinsically worthless.

-- Ex.: U.S. paper money - only other value is as paper

-- Fiat money has value only because the government declares it to

be legal tender and because people believe it has value.

---- LEGAL TENDER: money that a government has required

to be accepted as payment for debts.

Measuring the price level and inflation:

The price level is the average level of dollar prices in an economy.

Index numbers are a series of number used to track a variable’s

rise and fall over time.

An index is a series of numbers, each one representing a different

period. Index numbers are only meaningful in a relative sense: we

compare one period’s index number with that of another period

and can quickly see which one is larger and by how much. The

actual number for a particular period has no meaning in and of

itself.

What are index numbers?

Value of measure in current period

*100

Value of measure in base period

Index numbers are values expressed as a percentage of a single base figure. For example,

if annual production of a particular chemical rose by 35%, output in the second year was

135% of that in the first year. In index terms, output in the two years was 100 and 135

respectively.

An index will always equal 100 in the base period.

How to construct a price index:

A price index measures the cost of buying a certain "basket" of goods, so one must:

(1) total up the dollar cost of buying given quantities of all of the items in the basket,

for each of the years we are looking at.

Then, so that we may more easily compare price levels for different years, we index those

cost totals to the however much it costs to buy that basket of goods in the base year,

which is whatever year we choose to be our basis of comparison. Thus, we must

(2) choose a base year. Then, for each year, compute the price index by dividing the

total cost of the basket of goods in that year by the total cost of that basket of goods

in the base year, and then multiply by 100. So the price index for the base year is

always 100, because we're dividing a number by itself and then multiplying by 100. If the

same basket of goods costs 4% more (i.e., 104% as much) in the next year, then the next

year's price index is 104.

price index for year t = 100 * (cost total for year t)/(cost total for base year)

Example of constructing a price index and calculating the inflation rate from it:

Imagine the same small island economy that we used in our nominal-vs.-real GDP

example from earlier. In 1995, which we will use as our base year, the average person

there consumed just three commodities -- beer, pretzels, and bicycles -- in the following

quantities:

1995

Commodity

p

q p*q

Case of beer

$20 1

Bag of pretzels

$1

Bicycle

$200 1 +$200

$20

20 + $20

TOTAL COST OF GOODS

$240

-- Since 1995 is the base year, the price index for 1995 is: {$240/$240} * 100 = 100

-- -- In 1996, the price of beer was still $20, and the price of a bag of pretzels rose to

$1.50 and the price of a bike rose to $210. Now that same basket of goods costs a bit

more:

Commodity

1996 1995

p

q

p*q

Case of beer

$20

Bag of pretzels

$1.50 20

+ $30

Bicycle

$210 1

+$210

TOTAL COST OF GOODS

1

$20

$260

: -- In 1996, the price index was: {$260/$240} * 100 = 1.0833 * 100 = 108.33

-- The 1996 inflation rate was just the difference between the two, or 8.33%. To verify:

1996 inflation rate = {(108.33/100) - 1} * 100

= (1.0833 - 1) * 100

= .0833 * 100

= 8.33%

Types of price indexes:

GDP price index

Consumer price index (CPI)

Producer price index (PPI) (previously known as the wholesale price index)

The Consumer Price Index:

Definition: Consumer Price Index: an index of the

cost, through time, of a fixed market basket of

goods purchased in some base period.

In recent years, the base year for the CPI has

been 1983, so following our general formula for

price indexes, the CPI is calculated as:

Cost of market basket in current year

*100

Cost in market basket of 1983

“The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is the ratio of the value of a basket of goods in the

current year to the value of that same basket of goods in an earlier year. It measures the

average level of prices of the goods and services typically consumed by an urban

American family. Parkin, 1990”

According to the BLS:

“The CPIs are based on prices of food, clothing, shelter, and fuels,

transportation fares, charges for doctors’ and dentists’ services, drugs,

and other goods and services that people buy for day-to-day living.

Prices are collected in 87 urban areas across the country from about

50,000 housing units and approximately 23,000 retail establishmentsdepartment stores, supermarkets, hospitals, filling stations, and other

types of stores and service establishments. All taxes directly associated

with the purchase and use of items are included in the index. Prices of

fuels and a few other items are obtained every month in all 87 locations.

Prices of most other commodities and services are collected every month in

the three largest geographic areas and every other month in other areas.

Prices of most goods and services are obtained by personal visits or

telephone calls of the Bureau’s trained representatives.”

How the CPI has performed, selected years, 1960-2001 base year 1983 not shown =

100:

Year

Consumer Price Index

1960

29.8

1965

31.8

1970

39.8

1975

55.5

1980

86.3

1985

109.3

1990

133.8

1995

153.5

2000

174.0

2001

176.7

The CPI is a measure of price level in an economy

The rate of inflation is determined and measured by the Consumer Price

Index (CPI). The (http://www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htm) CPI is comprised of

a “basket of goods” of 400 items that include housing (40%), food and

beverages (17%), transportation (17%), medical care (7%), apparel (6%),

entertainment (5%), other (8%). Each year, the prices of these 400 good

and services are added up and compared to the base that was determined

by averaging the years 1982-1984. Thus, the CPI for 1950 was 24.1 which

means that 1950’s CPI was 24.1% of the base. In other words, prices in

1950 were only 24.1% of the prices being paid in 1982-1984. The CPI for

2001 was 177.1, that is, prices in 2001 were 177.1% of the prices being

paid in the base years (77% higher).

Inflation rate: the percent change in the price level from one period to the

next.

Deflation: a decrease in the price level from one period to the next. -- A major

deflation has not occurred in this country since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

A very minor one did occur in 1954, when the consumer price index fell 0.4%

(the inflation rate was -0.4%).

Rate of inflation =

New CPI – Old CPI

Old CPI

Let us suppose that the

The Formula used to calculate the inflation rate:

Inflation = a percentage change in CPI

Inflation =

CPI year 2- CPI year 1

*100

CPI year 1

Q: What is the inflation rate between 2002 and 2001?

A:

175-100

100

*100 = 75% inflation

Constructing the CPI: step 1: compute the cost

of a market basket in each year (prices times

quantities), step 2: choose a base year. Step 3:

Calculate the CPI for the current year by: (Cost

current year)/(cost in base year)*100. Side

implication: in the base year the CPI = 100. With

inflation, CPI increases.

The inflation rate via the CPI: (CPI current year

– CPI previous year)/CPI previous year all times

100. Note that this is just a percentage change. The

inflation rate is the percentage change in the CPI

from one period to the next.

Suppose only two goods are consumed:

1. Hot dogs

2. Hamburgers

Year

Price of Hot Dogs

Price of Hamburgers

2001

$1

$2

2002

$2

$3

Suppose the average person consumes:

a) 4 hot dogs

b) 2 hamburgers

The above figures are considered a fixed basket, therefore, the numbers do not change,

only the prices.

Task: Compute the basket’s cost:

By keeping the basket the same (combination of 4 hot dogs and 2 hamburgers)

only prices are allowed to change. This allows us to isolate the effects of price

changes over time.

An important fact: CPI quantity is fixed

Solution:

Cost in 2001 [$1*4] + [$2*2] = $8

Cost in 2002 [$2*4] + [$3*2] = $14

How the CPI is used: the CPI is one of the most important measures of the performance

of the economy: It is used as:

1) A policy target

2) To index payments;

Indexation: adjusting the value of some nominal payment in proportion to a price index,

in order to keep the real payment unchanged. A payment is indexed when it is set by a

formula so that it rises and falls proportionately with a price index. An indexed payment

makes up for the loss in purchasing power that occurs when the price level rises. Whose

benefits are indexed to the CPI? Social Security recipients and about ¼ of all union

members (5 million+ workers in the US) have labor contracts that index their wages to

the CPI. Since the 1980’s, the US income tax has been indexed as well—the threshold

income levels at which tax rates change automatically rise at the same rate as the CPI.

Real Variables and adjustment for inflation: You can monitor changes in purchasing

power by not focusing on the nominal wage—the number of dollars you earn—but on the

real purchasing power of your wage. To track real wage, we need to look at the number

of dollars you earn relative to the price level.

Calculating the real wage: Example from Hall/Liebermann (data above)

Real wage in any year =

Nominal wage in that year

*100

CPI in that year

$4.67

*100 $8.41

55.5

$14.64

Re al wage in 2001 =

*100 $8.29

176.7

Real wage in 1975 =

Thus, although the average worker earned more dollars in 2001 than in 1975, when we

use the CPI as our measure of prices, purchasing power seems to have fallen over those

years.

Thus: When we measure changes in the macroeconomy, we usually

care not about the number of dollars we are counting, but the

purchasing power those dollars represent. Thus, we translate

nominal values into real values by using the formula:

Real Value =

nominal value

*100

price index

Inflation and the measurement of real GDP: a special index is used to translate nominal

GDP figures into real GDP figures: the GDP price index.

Demand-pull inflation - spending increases faster than production

Cost-push inflation (or supply side inflation) - prices rise because of rise in per

unit cost of production - e.g. oil price, wage push by unions

The GDP price index measures the prices of all goods and services

that are included in U.S. GDP, while the CPI measures the process of

all goods and services bought by U.S. households.

The Costs of Inflation/The inflation myth: Most people

think that inflation—merely by making goods and services

more expensive—erodes the average purchasing power of

income in the economy. Because every market transaction

involves two parties—a buyer and a seller, the loss in the

buyers real income is matched by the rise is seller’s real

income. Inflation may redistribute purchasing power among

the population, but it does not change average purchasing

power, when we include both buyers and sellers in the picture.

Inflation can redistribute purchasing power

from one group to another, but it cannot, by

itself, decrease the average real income in the

economy.

$$The redistributive cost of inflation:

If nominal income rises faster than prices, then your

real income will rise;

fixed income groups will be hurt by inflation

Savers will be hurt by unanticipated inflation

Borrowers gain by unanticipated inflation - borrow

'dear' and pay back 'cheap'

If inflation is anticipated, the effects will be less

severe

One cost of inflation is that it often redistributes purchasing power

within society; “harming” the needy and helping those who are already

well off. Because some workers have nominal wage agreements that

span over long periods, even years, such as minimum wage inflation

can harm ordinary workers, since it erodes the purchasing power of

their pre-specified nominal wage. But the effect can also work the

other way; benefiting ordinary households and harming businesses: for

example, many homeowners sign a fixed dollar mortgage agreement

with a bank. These are promises to pay the bank back the same

nominal sum each month. Inflation can reduce the real value of these

payments, thus redistributing purchasing power away from the bank

and toward the average homeowner.

In general, inflation can shift purchasing power away from those who

are awaiting future payments specified in dollars, and toward those

who are obligated to make such payments.

Inflation does not mean that prices of everything in the economy are

rising. Inflation means that prices on “average” are rising. Some goods

and services prices even fall during the inflation period.

For example: Computer prices have fallen.

Expected inflation need not shift purchasing power: over any

period, the percentage change in a real value (%Real) is

approximately equal to the percentage change in the associated

nominal value (%Nominal) minus the rate of inflation:

%Real = %Nominal – Rate of Inflation

If the inflation rate is 10 percent, and the real wage

is to rise by 3 percent, then the change in the

nominal wage must (approximately) satisfy the

equation:

3 % = %Nominal – 10% %Nominal = 13%

Thus the required nominal wage hike is 13%

If inflation is fully anticipated, and if both parties take it into account, then inflation will

not redistribute purchasing power.

Nominal interest rate: the annual percent increase in a lenders

dollars from making a loan.

Real interest rate: the annual percent increase in a lender’s

purchasing power from making a loan.

Unexpected inflation does shift purchasing power: when inflationary

expectations are inaccurate, purchasing power is shifted between

those obligated to make future payments and those waiting to be paid.

An inflation rate higher than expected harms those awaiting payment

and benefits the payers; an inflation rate lower than expected harms

the payers and benefits those awaiting payment.

The resource cost of inflation: When people must spend time and other resources

coping with inflation, they pay an opportunity cost—they sacrifice the goods and

services those resources could have produced instead.“Using the Theory: Is the CPI

accurate?”

Limitations of CPI: Problems in measuring the cost of living

In reality, the CPI overestimates the actual inflation by 0.5 – 1.5%

Reasons for over calculation:

1) Substitution bias: When the price of one good increases, consumers

often respond by substituting another good in its place.

a) A good example of substitution bias is often seen between

products like Pepsi and Coca-cola.

Pepsi

Coca-cola

Last Month

$2

$2

This month

$2.10

$2

CPI will include these substitutable products into the CPI even

though they might not be purchase. CPI price will go up because

of Pepsi. This will bias the cost of living.

2) CPI cannot capture unmeasured quality change: Let us presume that

we buy a car today for $15,000. A car could be purchased 10 years ago

for $15,000. But did a car 10 years ago have an airbag or a CD player.

This is another disadvantage of CPI—that it cannot measure if the quality

or standards of quality have decimated.

3) New Technologies: The CPI still counts as inflation many causes in

which prices rise because of improvements in quality, not because the cost

of living has risen. This causes the CPI to overstate the inflation rate.

Example: cars are more reliable now and require less routine

maintenance, and have features like airbags and antilock brakes. The

BLS struggles to substantiate these changes—although they note that cars

have become more expensive, some of these rises in prices are not really

inflation, but the consumer is getting more.

4) Growth in discounting: The CPI omits reductions in the prices people

pay from more frequent shopping at discount stores and so overstates the

inflation rate.

The substitution bias, introduction of new goods, and unmeasured quality changes cause

the CPI to overstate the true cost of living.

Keep in mind that the measure of CPI is used to see if the cost of living has gone

up in a given period.

What is CPI and how is CPI useful?

Many government transfer programs such as social security benefits are

tied to the CPI.

Indexation: the automatic correction of a dollar amount for the effect of inflation

on a contract.

Indexation is also used by the private sector. Many private labor contracts

include COLA (cost-of-living-allowances) + 5 or 7%

A retired person would see his SSI check increase by 5% in the CPI went up by

5%.

Nominal Interest Rate vs. Real Interest Rate

1) Nominal interest rate: the rate as usually reported without a correction for

the effects of inflation

2) Real interest rate: the rate corrected for inflation

Real interest rate = nominal interest rate – inflation

Example: Person A borrows $100 from person B. Person B charges 5%

interest on the loan for a year. Inflation is 7%. Who is better and worse

off?

o Answer: Verify, though, person A is better off.