Document

advertisement

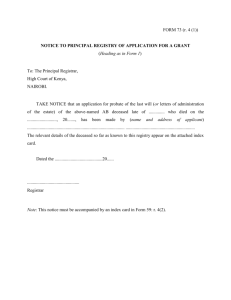

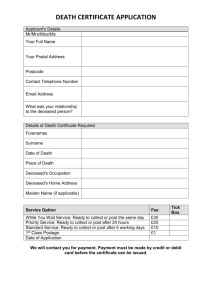

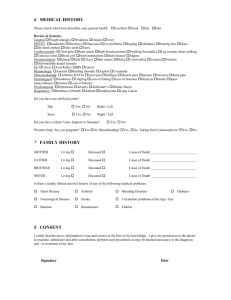

FAMILY PROVISION: OVERVIEW AND UPDATE 1. This is not an overview of the whole of the law of family provision. I am limiting myself primarily to sections 1 to 3 of the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975 “the 1975 Act”. A consideration of the index to the Act will show the wide range of areas that are not being covered tonight. As with ToLATA claims there is an overlap between Family law and the Chancery Division.. 2. Some important preliminary questions: (i) Did the deceased die intestate or intestate? (ii) If he died intestate how will the estate be distributed on intestacy? (iii)In the event of death what should be done? Should a caveat be lodged or should there simply be a standing search? (iv) What is probate? 3. It may be, depending upon the circumstances of the case,that the family law practitioner will need to seek the advice of a chancery practitioner on one or more of these issues. Did the deceased die testate or intestate? 4. On the face of it this may seem a stupid question. Either there is a Will or there is no Will. However, questions may arise as to whether or not the Will has been executed properly: was the deceased of sound mind at the time the Will was made? Was there a want of knowledge and approval? Was the Will validly executed? Had the Will been revoked? What was the effect of any codicil to the Will? In the majority of cases there will be a Will that, it can be shown, was validly executed. However, there are elephant traps for the unwary. At the very least the practitioner should ask whether or not there is a valid and duly executed Will. See for example: Gill –v- Gill [1909] P 157. Devolution of the estate on intestacy 1 5. The devolution of an estate on intestacy is governed by section 46 of the Administration of Estates Act 1925. At Appendix One there is a flow chart produced by the Law Commission at paragraph 2.91 of its Consultation Paper No 191 on Intestacy and Family Provision Claims on Death. Practitioners should note that the Law Commission intends to publish its Report with its Recommendations in “winter 2011 / 2012”. Their provisional proposals, as to intestacy contained in the Consultation Paper are that: (i) Where a spouse dies intestate and is survived by a spouse but no dependents then the entirety of the estate should go to the surviving spouse whether or not there are other family members surviving; (ii) There should be a revised and simplified definition of “personal chattels” and it should exclude items used by the deceased exclusively or principally for business purposes at the date of his or her death; (iii)That the level of the statutory legacy (if it is retained) should be reviewed at least every five years; (iv) If the statutory legacy is retained and if it is still required to be linked to house prices it should be raised in line with the average rise in house prices across England and Wales on each review; (v) The cohabitant of a deceased should have an entitlement on intestacy subject to certain conditions; (vi) For the purposes of the intestacy rules a cohabitant should be defined as a person who, immediately before the death of the deceased, was (1) living with the deceased as a couple in a joint household; and (2) was neither married to nor a civil partner of the deceased. (vii) If the deceased and a surviving cohabitant are by law the parents of a child born before, during or following their cohabitation (1) there should be no minimum duration requirement for an entitlement on the intestacy of the deceased; and (2) the surviving cohabitant should be entitled under the intestacy rules to the same entitlement as a spouse; (viii) Any duration requirement for a cohabitant should only be fulfilled by a continuous period of cohabitation; 2 (ix) If the deceased and the cohabitant had not had a child together the surviving cohabitant should be entitled to the same entitlement as a surviving spouse if the cohabitation had continued for at least five years before death; (x) If the cohabitation had endured for between two and five years and there were no children of the relationship the surviving cohabitant should be entitled under the intestacy rules to 50% of the entitlement that a spouse would have received from the estate; (xi) If the deceased and the surviving cohabitant had a child before, during or following their cohabitation or their cohabitation lasted at least five years prior to the death then the surviving cohabitant should be entitled to all of the deceased’s personal chattels outright; (xii) If the deceased and the surviving cohabitant did not have a child and the cohabitation lasted between two and five years prior to the death then the surviving cohabitant should be entitled to exercise a right of appropriation over the deceased’s chattels up to the value of his or her entitlement under the intestacy rules; (xiii) A surviving cohabitant should have no entitlement under the intestacy rules if the deceased left a surviving spouse; (xiv) If the surviving cohabitant and the deceased are by law together the parents of a child, there should be no minimum duration requirement for the survivor to be entitled to apply under section 1(1)(ba) of the 1975 Act provided that the cohabitation was continuing at the date of death; (xv) In all cases, in order to qualify for an award under the 1975 Act as a cohabitant the applicant must have been living as a couple in a joint household with the deceased immediately before the death; Some useful probate terms 6. The following terms may be of use: “probate” means in basic terms proof that the Will subject to probate is the last will of the deceased. A probate claim is defined in CPR r.57.1.(2)(a) “personal representatives” – these are either administrators (administratrices being the female of the term) or executors (executrix/executrices being the 3 female of the term) and are charged with the administration of the estate of the deceased If the deceased has executed a valid will then the persons charged with administering his estate are his / her executors; If the deceased has died intestate then the persons charged with administering his estate are his / her administrators (administratrix/administratrices) – note that the order of precedence of personal representatives is governed by the Non-Contentious Probate Rules 1987; “standing search” – a provision whereby, on payment of a prescribed fee, an office copy will be sent of any grant which corresponds with the particulars contained in the application – this is the way in which when a practitioner knows that someone has died and that his client may have a claim under the 1975 Act the practitioner can know when probate has been granted and when the 6 month time limit begins to run. To ensure that a claim is brought in time when there is no question in relation to the validity of the Will a standing search will ensure that the applicant/the applicant’s advisers know about when probate has been granted. If there is no challenge to the Will then a caveat (see below) is the wrong way forward and the wrongful entry of a caveat may result in costs orders against the person entering it1. “Caveat” – a notice in writing that no grant of probate is to be sealed in the estate of the deceased named without notice to the caveator. The principal object of a caveat is to enable a person who is considering opposition to a grant to obtain evidence or legal advice in the matter. If a caveat is entered no grant can be entered until it is removed or ceases to have effect. It normally remains in effect for 6 months although it can be renewed. A caveat is usually used when there is to be a challenge to the Will (e.g. when it is suggested that it is not the last Will or that it was procured by undue influence or where there was a want of knowledge and approval on the part of the testator). It is not appropriate where there is merely an intention to bring a claim against the testator’s estate on the grounds that there has been less than reasonable provision. 1 See Rule 44 of the Non Contentious Probate Rules 1987 for the procedure for obtaining a caveat and for warning one off 4 “donatio mortis causa” a gift made in contemplation of death Freedom of testamentary expression 7. Generally speaking a testator is entitled to leave his property, if governed by English law in whatever way he may choose. He is under no obligation to leave his estate (or any part of it) to anyone in particular. He is under no obligation to behave fairly, reasonably or explicably. Per Lord Neuberger MR in Gill –vWoodall [2010] EWCA Civ 1430: “Subject to statutes such as the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975, the law in this country permits people to leave their assets as they see fit, and experience of human nature generally, and of wills in particular, demonstrates that peoples’ wishes can be unexpected, inexplicable, unfair and even improper.” 8. Freedom of testamentary expression is circumscribed by the 1975 Act. There have been gradual incursions into freedom of testamentary expression since the Inheritance (Family Provision) Act 1938 (“the 1938 Act”). It must, however, be clearly understood that the limitations on testamentary freedom are statutory and so it is always important to consider the terms of the statute when advising someone with a potential claim under the 1975 Act. Domicile 9. Section 1(1) of the 1975 Act provides that: “Where after the commencement of this Act a person dies domiciled in England and Wales and is survived by any of the following persons …” 10. Therefore if a person was not domiciled in England and Wales at the time of his death there is no jurisdiction to entertain an application under the 1975 Act. Mere residence within England and Wales is not enough without domicile. In Agulian –v- Cyganik [2006] 1 FCR 4062 Longmore LJ was very critical of 2 In this case the deceased left an estate worth £6.5 million in the UK. The deceased had been born in Cyprus in 1939 but had lived and worked in the UK from the age of 19 for 43 years until 5 reliance on the “somewhat antiquated notion of domicile” and suggested that the terms of section 1 should be reconsidered with a reference to “habitual residence” replacing domicile. The Law Commission in its Report on Cohabitation: the Financial Consequences of Relationship Breakdown (Law Com No 307) stated that the law here was ripe for reconsideration although it fell outside the ambit of that report. In the Consultation Paper on Inheritance (No 191) referred to above the Law Commission has provisionally recommended, at paragraph 8.38, that the requirement for domicile should be scrapped. They enquired at paragraph 8.39 whether it should instead be a precondition to an application that the deceased died habitually resident in England and Wales or whether an application for family provision should be possible in any case where there was property comprised in the estate that was governed by English succession law. 11. It is beyond the scope of this paper to consider domicile in any depth. However, it is vitally important that the practitioner be satisfied that the deceased was domiciled in England and Wales before launching the application. The burden of proof is on the applicant to satisfy the court on the usual civil standard that the deceased died domiciled in England and Wales. 12. It should also be borne in mind that the determination of the issue of domicile may also have tax consequences. Persons who may bring a claim under the 1975 Act 13. Section 1(1) of the 1975 Act, as amended by section 2 of the Law Reform (Succession) Act 1995 and Section 71, Schedule 4, paras 15(1) to (5) of the Civil Partnership Act 2004 provides that where a person dies domiciled in England and Wales and is survived by any of the persons therein set out (see hand out): his death in 2003. He left his partner £50,000 (to whom he had become engaged four years before his sudden and unexpected death). His partner had brought a claim under the 1975 Act and at first instance had persuaded the court that the deceased was domiciled in England and Wales so that she had a viable claim. The Court of Appeal, with very little enthusiasm, allowed an appeal by the personal representatives. The deceased’s domicile remained Cypriot and his partner had no claims under the 1975 Act. 6 That person may apply to the court for an order under s. 2 of the Act on the ground that the disposition of the deceased’s estate affected by his Will or the law relating to intestacy or the combination of his Will and that law, is not such as to make reasonable financial provision for the applicant. Reasonable financial provision 14. Section 1(2) of the 1975 Act states “In this Act “reasonable financial provision” (a) In the case of an application made by virtue of subsection 1(a) above by the husband or wife of the deceased (except where the marriage with the deceased was subject of a decree of judicial separation and at the date of death the decree was in force and the separation was continuing), means such financial provision as it would be reasonable in all the circumstances of the case for a husband or wife to receive, whether or not that provision is required for his or her maintenance; (aa) In the case of an application made by virtue of subsection 1(a) above by the civil partner of the deceased (except where at the date of death, a separation order under Chapter 2 of Part 2 of the Civil Partnership Act 2004 was in force in relation to the civil partnership and the separation was continuing), means such financial provision as it would be reasonable in all the circumstances the case for the civil partner to receive, whether or not that provision is required for his or her maintenance. (b) In the case of any other application made by virtue of subsection (1) above, means such financial provision as it would be reasonable in all the circumstances of the case for the applicant to receive for his maintenance. 7 (3) For the purposes of subsection 1(e) above, a person shall be treated as being maintained by the deceased, either wholly or partly, as the case may be, if the deceased, otherwise than for full valuable consideration, was making a substantial contribution in money or money’s worth towards the reasonable needs of that person.” 15. It can be seen that spouses and civil partners are entitled to greater provision than any other applicant. Other applicants are limited to what is required for that applicant’s maintenance. In determining whether or not the deceased has made reasonable financial provision an objective test should be used. It is not a question of whether or not the deceased acted unreasonably but whether, looked at objectively, the disposition to the applicant (or lack of it) produces an unreasonable result in that it does not make reasonable financial provision for the applicant3. In answering that question the court must have regard to all the factors set out in section 3 of the Act. 16. Section 3(2) of the Act states: “This subsection applies, without prejudice to the generality of paragraph (g) of subsection (1) above, where an application for an order under section 2 of this Act is made by virtue of section 1(1)(a)4or (b)5of this Act. The court shall, in addition to the matters specifically mentioned in paragraphs (a) to (f) of that subsection, have regard to the age of the applicant and the duration of the marriage or civil partnership; the contribution made by the applicant to the welfare of the family of the deceased, 3 See the judgment of Oliver J in Re Coventry [1980] Ch 461. Claim by a spouse or civil partner of the deceased 5 Claim by former spouse or civil partner of the deceased who has not formed a subsequent marriage or civil partnership 4 8 including any contribution made by looking after the home or caring for the family; In the case of an application by the wife or husband of the deceased, the court shall also, unless at the date of death a decree of judicial separation was in force and the separation was continuing, have regard to the provision which the applicant might reasonably have expected to receive if on the day on which the deceased died the remarriage, instead of being terminated by death, had been terminated by a decree of divorce.” In the case of an application by the civil partner of the deceased, the court shall also, unless at the date of death a separation order under Chapter 2 of Part 2 of the Civil Partnership Act 2004 was in force and the separation was continuing, have regard to the provision which the applicant might reasonably have expected to receive if on the day on which the deceased died the civil partnership, instead of being terminated by death, had been terminated by a dissolution order.6” 17. The Law Commission has proposed provisionally that the 1975 Act should be amended so that “reasonable financial provision” for a cohabitant is defined as such financial provision as it would be reasonable in all the circumstances of the case for the applicant to receive whether or not that provision is required for the applicant’s maintenance. The “notional divorce” 6 See paragraphs 3.145 to 3.150 of the Law Commission Consultation Paper No 191 for criticism of this wording. At paragraph 3.147 “We can also understand why, at first sight and without the benefit of legal advice, some bereaved spouses may feel that the present statutory provision raises an inappropriate equivalence between termination of a relationship by death and termination of the same relationship by divorce. However, in the light of the importance of the provision and the need to ensure that the interests of a surviving spouse are properly safeguarded, we think that there is no alternative to having a reference to divorce or dissolution in the statute.” 9 18. Thus the Court must, when considering a claim from a surviving spouse / civil partner, carry out the “notional divorce” exercise taking into account the age of the applicant, the duration of the marriage and the contributions made by the applicant to the welfare of the family of the deceased. Although at one time there was some doubt as to how the notional divorce exercise should be completed the approach of Oliver LJ in Re Besterman [1984] FLR 503 has now been approved as the right one7. He said: “In an application under [the 1975 Act] however, the figure resulting from the section 25 exercise is merely one of the factors to which the Court is to “have regard” and the overriding consideration is what is “reasonable” in all the circumstances. It is obviously however a very important consideration and one which the statute goes out of its way to bring to the court’s attention.” 19. In P –v- G, P and P [2006] 1 FLR 431 Black J held that when assessing the relevant assets there was a potentially uneasy interplay between the obligation of the court under s.3(2) of the 1975 Act to have regard to the provision which the applicant might reasonably have expected to receive if there had been a divorce rather than a death, which might dictate a historical view of the value of the assets, and the obligation to take into account the facts as known to the court at the date of the hearing under s.3(5). The objective of the statute, she found, could be achieved without embarking upon a slavish and wholly artificial comprehensive enactment of the ancillary relief process involving, for example, the sterile process of calculating CGT which it was known would not be payable, or the artificial 7 See Re Krubert [1997] 1 FLR 42 10 process of factoring in costs of sale when there was no intention to sell any of the assets. The more pragmatic approach was to use, for the purposes of s 3(2) the actual value of the assets as at the date of the hearing. The statute did not contemplate the playing out of the entire fictional ancillary relief case, but rather that the court should simply reach a sufficient conclusion about how it would have been resolved and take that factor into account in considering what would be reasonable financial provision under the 1975 Act. Section 3(2) and the former matrimonial home 20. In Miller / MacFarlane Lord Nicholls stated at paragraph [22] that the parties’ matrimonial home, even if brought into the marriage at the outset by one of the parties, usually had a central place in any marriage. In other words, the matrimonial home should be regarded as matrimonial property. This is not a view that has been wholeheartedly accepted in the subsequent authorities. However, in Iqbal –v- Ahmed [2011] EWCA Civ 900 Gross LJ said, at paragraph 17(iii) that whether or not these dicta constituted a proposition of the law did not matter. They were, he said, on any view, of powerful persuasive force. He went on to say at paragraph [22]: “Given the significance of the matrimonial home, as commented upon by Lord Nicholls in Miller –v- Miller (supra), the award of a capital share in the property to the widow, in the circumstances of this case, seems to me appropriate, the more especially as it is by this means, if at all, that reasonable financial provision (and hence security) can be made for her.” 11 Notional divorce and pre-nuptial or post-nuptial agreements 21. It would appear to follow that, in the event that there is a pre- or post-nuptial agreement in place, in light of Radmacher –v- Granatino [2010] 2 FLR 1900 that a court when conducting the “notional divorce” exercise would have to take that agreement into account. However, as the “notional divorce” exercise is only one of the facts, albeit an important one, the court’s main task would still be to decide whether or not the deceased made reasonable financial provision for the applicant and, if not, what would constitute reasonable financial provision taking into account all the factors within section 3(1) and 3(2). 22. As to the issue of the duration of the marriage see Wall LJ in Fielden –v- Cunliffe [2006] 1 FLR 745: “As I have already indicated, there is, self-evidently, a profound difference between a marriage which ends through the death of one of the spouses, and a marriage which ends through divorce. For present purposes, some elementary facets of that difference suffice. A marriage dissolved by divorce involves a conscious decision by one or both of the spouses to bring the marriage to an end. That process leaves two living former spouses, each of whom has resources, needs and responsibilities. In such a case the length of the marriage and the parties' respective contributions to it assume a particular importance when the court is striving to reach a fair financial outcome. However, where the marriage, as here, is dissolved by death, a widow is entitled to say that she entered into it on the basis that it would be of indefinite duration, and in the expectation that she would devote the remainder of the parties' joint lives to being his wife and caring for him. The fact that the marriage has been prematurely terminated by death after a 12 short period may therefore render the length of the marriage a less critical factor than it would be in the case of a divorce.” The spouse of the deceased / void marriages 23. The applicant must have been party to a valid marriage. If a surviving applicant was party to a void marriage or civil partnership that survivor is not entitled to claim on the deceased’s intestacy as a “spouse” or “civil partner”. But, sections 25(4) and 25(4A) of the 1975 Act provides that if such a person entered into a void marriage in good faith that person shall be treated as a spouse or civil partner unless either (a) that marriage / civil partnership was dissolved or annulled during the lifetime of the deceased and that dissolution / annulment is recognised by the law of England and Wales; or (b) the survivor has during the lifetime of the deceased entered into a later marriage / civil partnership. To establish “good faith” the applicant must satisfy a court that (a) he / she considered the ceremony to be in the nature of a marriage and (b) he / she did not know or had no suspicion that the marriage was a void one: see Gandhi -v- Patel [2002] 1 FLR 603. Bigamous marriages 24. A person who has committed bigamy is unlikely to be able to rely upon section 25(4) but would be able to claim under one of the other classes of dependents, though bigamy may be regarded as conduct within section 3(1)(g) of the Act. Judicially separated spouses 25. The surviving spouse may qualify within section 1(1)(a) of the 1975 Act although they would not receive the higher standard of reasonable financial provision within section 1(2)(a). If the separation was informal, by agreement or deed, and there has been no decree of judicial separation an applicant may still fall within section 1(1)(a). Polygamous marriages 26. Whilst English law does not recognise polygamous marriages so that a marriage that takes place within England and Wales, the surviving spouse of a polygamous 13 marriage recognised as valid under English law will be entitled to claim. See Official Solicitor –v- Yemoh [2010] EWHC 3727 (Ch) for a discussion of polygamous marriages within the context of the 1975 Act. A polygamous marriage will be void if either party to the marriage is domiciled in England and Wales at the time of the marriage. See Dicey & Morris: Conflict of Laws (14th Edition) Rule 73. See also section 5 of the Private International Law (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1995. Sections 14 and 14A of the 1975 Act 27. Under these sections if the decree of divorce or nullity of marriage has been made absolute or a decree of judicial separation has been granted within a year of the death and an application for financial remedies has not been made or has been made but has not been determined (or the like position exists for a surviving civil partner) then the court shall, if it thinks it just to do so, treat that applicant for the purposes of the application as if the decree of divorce or nullity of marriage had not been made absolute or the decree of judicial separation had not been granted (with the like provisions for surviving civil partners). Remarriage by a surviving spouse 28. If the surviving spouse remarries after making a claim under the 1975 Act but before that claim is resolved the status and eligibility of that applicant is not affected by the remarriage although the fact of the remarriage will be taken into account as one of the factors within section 3(1) of the 1975 Act. If however the surviving former spouse / civil partner has remarried or formed a subsequent civil partnership prior to the death the applicant will not be eligible to claim – see section 1(1)(b). Final Financial Remedy Order directing pursuant to section 15 of the 1975 Act that the spouse will have no claim against the other’s estate in the event of that other’s death 29. If the final order directs that no claims may be brought under the 1975 Act on the death of the other spouse then, self-evidently, no claim can be brought under the 1975 Act in the event of that other party’s death. Claims by a person who had lived with the deceased for the whole of the period of two years ending immediately before the death of the deceased in the same household as the spouse / civil partner of the deceased 14 30. This provision was enacted in the Law Reform (Succession) Act 1995 and dealt originally with the position of heterosexual cohabitees. It was extended to cover homosexual cohabitees by the Civil Partnership Act 2004. The statute refers to “household” rather than “house”. See Ward LJ in Gully –v- Dix [2004] 1 FLR 918: “Thus the claimant may still have been living with the deceased in the same household as the deceased at the moment of his death even if they had been living separately at that moment in time. The relevant word is "household" not "house", and "household" bears the meaning given to it by Sachs LJ8. Thus they will be in the same household if they are tied by their relationship. The tie of that relationship may be made manifest by various elements, not simply their living under the same roof, but the public and private acknowledgment of their mutual society, and the mutual protection and support that binds them together. In former days one would possibly say one should look at the whole consortium vitae. For present purposes it is sufficient to ask whether either has demonstrated a settled acceptance or recognition that the relationship is in truth at an end. If the circumstances show an irretrievable breakdown of the relationship, then they no longer live in the same household and the Act is not satisfied. If, however, the interruption is transitory, serving as a pause for reflection about the future of a relationship going through difficult times but still recognised to be subsisting, then they will be living in the same household and the claim will lie. Just as the arrangements for maintenance may fluctuate, using Stephenson LJ's expression9 cited above, so the steadfastness of a commitment to live together may wax and wane, but so long as it is not extinguished, it survives. These notions are 8 9 In Santos –v- Santos [1972] Fam 247, [1972] 2 WLR 889, [1992] 2 AER 246 See Jelley –v- Iliffe[1981] Fam, [1981] 2 WLR 801, [1981] 2 AER 291. 15 succinctly encapsulated in the judge's test, which was to ask whether the relationship was merely suspended, and I see no error in his approach.” 31. In Re Watson [1999] 1 FLR 878 where the applicant was living with the deceased but their relationship was not sexual Neuberger J said “the court should ask itself whether, in the opinion of a reasonable person with normal perceptions, it could be said that the two people in question were living together as husband and wife, but when considering that question one should not ignore the multifarious nature of marital relationships.” 32. In Churchill –v- Roach [2004] 2 FLR 989 HHJ Norris QC, citing the above passage and went on to say: “In that case he was concerned to consider the question whether the absence of sexual relations meant that two people living together were not thereby living as husband and wife. In the instant case I have no doubt that Arnold and Muriel did enjoy sexual relations. The question in this case, it seems to me, is whether they were living in the same household and living as husband and wife, whatever the state of their sexual relations. It is, of course, dangerous to try and define what "living in the same household" means. It seems to me to have elements of permanence, to involve a consideration of the frequency and intimacy of contact, to contain an element of mutual support, to require some consideration of the degree of voluntary restraint upon personal freedom which each party undertakes, and to involve an element of community of resources. None of these factors of itself is sufficient, but each may provide an indicator. If I adopt that approach in 16 relation to what was happening between Muriel and Arnold in the seven months preceding December 1998, I would reach the conclusion that they were essentially maintaining two separate households. I do not regard it as fatal that two separate properties were involved: Shakespeare Avenue and 7 Ferry Lane. It is perfectly possible to have one household and two properties. But what does seem to me to be the case is that there were two separate establishments with two separate domestic economies. There was, of course, a degree of sharing when the two met at weekends and some of those weekends were long. But that does not mean that they lived in one household. On that ground I reject the claim under this head, because the claimant cannot satisfy the two year requirement.10” 33. A more recent case is that of Lindop –v- Agus [2010] 1 FLR 631. In that case the man and woman began a relationship with each other while working together; the man was a dentist and the woman a part-time dental nurse. The man was living in his own home; the woman was living with her father. Within a year the man asked the woman to move in with him; the woman, who was wary following a recent divorce, nonetheless agreed to make a gradual move to the man’s house. Both the man and the woman had children from previous relationships. When the couple had been in a relationship for approximately 5 years, the man died of a brain haemorrhage, aged 37. The woman sought to bring a claim under the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975. The only issue at the hearing was whether she was eligible to make such a claim, either as a person living with the man ‘in the same household as his wife’, within s 1(1A) of the 1975 Act, or as a person being maintained by the man otherwise than for full consideration 10 See generally Kotke –v- Saffarini [2005] 2 FLR 517 and Lindop –v- Agus [2010] 1 FLR 631; for cases on what is required to show cohabitation see Crake –v- Supplementary Benefits Commission [1982] 1 AER 498 and Kimber –v- Kimber [2000] 1 FLR 383. For a recent case applying Re Watson see Baker –v- Baker [1008] 2 FLR 767 17 immediately before his death, within s 1(1)(e). The executors’ case was that throughout the relationship the woman had retained her father’s address as her address for all official purposes, including bank statements, P60s, and the electoral register. The woman’s father had paid full council tax, without claiming the single occupancy discount. However, the woman’s father gave evidence that she had not been living with him at his address, although he accepted that from time to time the woman’s daughter was delivered back to his address following contact with the woman’s former husband. According to the evidence of the other witnesses the man and woman had been living together as a couple at the time of the man’s death: the couple had redecorated the house and bought furniture together; the woman bought most of the food and did most of the cooking; the couple had shared a bedroom, which was where the woman kept her clothes; and they had arranged their weekends so that their children stayed with them at the same time. In one of the court applications relating to the woman’s daughter, the woman had given the address of her father as her own address. However, in response, the woman’s former husband had written to the Legal Services Commission to inform them that although the woman was using her father’s address, in fact she resided permanently at the man’s address, which was where contact with the daughter took place. In addition the woman insured a car, allegedly given to her by the man, at the man’s address. The woman explained her use of her father’s address as a way of keeping her former husband as far away from her life as possible, and also said that she had simply not got round to changing everything, because she did not receive a lot of mail and there was no difficulty in getting what there was from her father. 18 34. HHJ Behrens found in favour of the woman. The question whether two people live together in the same household is essentially one of fact. Here, the court was satisfied that the man and woman had been living in the same household for a period of at least 2 years (and probably for over 3 years) before the man’s death; the woman was, therefore, eligible to make a claim under s 1(1A) of the Inheritance (Provision for Family and Dependants) Act 1975. The court found as a fact that the couple had been living together under the same roof: this had not been a case of there being two separate households and two separate properties. Applying the criteria in Kotke v Saffarini [2005] EWCA Civ 221, there had been a stable sexual relationship, the man had provided financial support, and the couple had cared for the children together. Most of the evidence pointed to the couple living openly together and displaying this to the outside world. The court was also satisfied that the woman was being maintained by the man immediately before his death, at least in part, and so she was also eligible to make a claim under section 1(1)(e). For the whole of the two years ending immediately before the death of the deceased as husband and wife 35. It is a question of fact and common sense as to whether or not an applicant can satisfy these requirements. The court will take into account periods of absence and will also consider the reasons for the absences and whether they were voluntary or involuntary as in the case where, for example, the deceased spends his last weeks or months in hospital. This is what happened in Re Watson [1999] 1 FLR 878 where the deceased died three weeks after going into hospital with his final illness. Neuberger J said: “As a matter of ordinary language, the fact that someone is in hospital for a period, possibly a long period, at the end of which he dies, does not mean that, before his death, he ceased to be part of the household of which he was part, until he was forced by illness to go into hospital, and to which he would have returned had he not died.” 19 36. Note also that in cases involving cohabitants the practitioner should have regard to section 3(2A) which provides that: (2A)Without prejudice to the generality of paragraph (g) of subsection (1) above, where an application for an order under section 2 of this Act is made by virtue of section 1(1)(ba) of this Act, the court shall, in addition to the matters specifically mentioned in paragraphs (a) to (f) of that subsection, have regard to— (a) the age of the applicant and the length of the period during which the applicant lived as the husband or wife or civil partner of the deceased and, in the same household as the deceased; (b) the contribution made by the applicant to the welfare of the family of the deceased, including any contribution made by looking after the home or caring for the family. 37. A recent case dealing with cohabitants is Cattle –v- Evans [2011] 2 FLR 843. The man and woman were in a close relationship for about 18 years with one substantial break lasting one and a half years; at one stage the couple became engaged, but never married; both had children by previous relationships. For the majority of the relationship the couple retained separate houses, and their finances were completely separate. Then, a few years after their reconciliation, the couple jointly purchased a property in Spain, on the basis that this would be their permanent home. The man sold his house first, and used the proceeds of sale to purchase the Spanish property; when the woman sold her property, she invested in a house with the aim of obtaining a rental income from it once her children no longer needed it, and also contributed to the considerable renovation work on the Spanish property. After only 4 years in Spain, the couple sold the Spanish property, having decided to live in Wales, where the man had apparently always wanted to live. They divided the proceeds of the sale equally. Before the purchase of their chosen Welsh property went through, but after they were already established in Wales, the man was diagnosed with 20 terminal lung cancer. The purchase went ahead, but the man bought the Welsh property himself, using his share of the proceeds of the Spanish sale: the woman made no significant financial contribution to the purchase and the property was registered in the man’s sole name. Although draft wills were prepared on the woman’s instructions, providing that the man would leave the Welsh property and his pension to her, with the residue to his own children, the man did not sign this will, and died intestate. The man’s estate was worth about £220,000 in total, including the Welsh property, currently valued at about £150,000. The woman, who was now 60, claimed that she should be awarded about £185,000 from the estate as reasonable financial provision; in the alternative she claimed a beneficial interest in the Welsh property under a constructive trust, claiming that it had always been intended to be a joint purchase, but had been put into the man’s sole name for tax reasons. The beneficiaries under the intestacy rules, the man’s two sons, claimed that the couple had been close to breaking up, and that the man had specifically told them that the estate was to be theirs. The woman had her own property with equity of about £100,000, but the rental from this was her only substantial source of income; she was likely to be able to recover about £20,000 loaned to one of her children and she had used £29,000 in savings to purchase a caravan. 38. Kitchin J awarded the woman a life interest in a property worth no more than £110,000, to be held on trust for the man’s sons – (1) On the evidence the man and woman had intended and understood that the man was not only the legal but also the beneficial owner of the Welsh property, and this position had not changed or evolved over time. It was relevant that: the couple’s only ‘joint’ property had been the Spanish property; all other monies and assets had been kept separate throughout; the woman had made independent use of her own assets throughout the relationship; the man had almost entirely funded the purchase of the Welsh property; there was evidence that the relationship had been under some strain and, despite their engagement, the couple had never married; the 21 terms of the draft wills were not consistent with the existence of a constructive trust (see paras [34]–[41]). (2) Given the long-standing relationship between the woman and the man, their cohabitation for about 5 years, and generally the commitment the woman had shown to the man, the man had not made reasonable financial provision for the woman. However, the draft wills did not reflect the man’s own approach to his responsibilities and obligations towards the woman: the man had not intended to make a will in the form of the draft wills, which had been drafted on the woman’s instructions alone. Given the size of the estate, the woman’s approach to her own assets and the woman’s conduct, the woman reasonably required to be housed in a property that would allow her to continue to enjoy a rental income from her existing property. However, the new property did not need to be of same size and value as the Welsh property; something of the size of the woman’s rental property would be appropriate, and the purchase price should in any event be no more than £110,000. The woman was to have a life interest in this new property, which was to be held on trust for the man’s sons: the woman was to keep the new property comprehensively insured to its full reinstatement value (see paras [51]–[58]). Same sex cohabitees 39. The most recent case regarding an alleged cohabiting same sex couple was Baynes –v- Hedger [2008] 2 FLR 1805. In this case there were two claimants against the deceased’s estate: a lady (Margot) who claimed to be in a long-term same sex relationship with the deceased (Mary) and Margot’s daughter (and Mary’s goddaughter) who claimed that she was being supported by the deceased at the time of her death so that she could bring herself within section 1(1)(e) of the 1975 Act. Both claims failed. The daughter appealed to the Court of Appeal which rejected her appeal. At first instance Lewison J applied the same “household” test as is used in heterosexual cohabitation cases. Equally importantly he concluded that it was not possible to establish that there was a cohabiting relationship if it was not acknowledged as such in the wider world: 22 “[149] There can, in my judgment, be no question but that Margot’s main residence was in Kingston; and Mary’s was at Dunshay Manor. This was the state of affairs that had prevailed since the late 1970s. It was, therefore, the settled pattern. It was not a temporary situation. Mary herself regarded Oak Tree Cottage as Margot’s home, rather than their joint home or one of their joint homes. This is made plain not only by her letter to Lizzie of September 2003 in which she refers explicitly to the ‘smooth running of Margot’s … household’, but also, tellingly, by the card that she wrote to Margot in October 2004 asking for permission to come and ‘stay’. The language in which that card is couched does not suggest one who was going to her own (or a joint) household. It is equally plain that Mary regarded Dunshay as her home and not as the (or a) joint home of her and Margot. There is, for example, no evidence that she consulted Margot about the gift of Dunshay to the Landmark Trust, even though she had made her decision before Margot’s health deteriorated in 2003; nor about what (if any) conditions should be attached to the gift. In addition her original will executed in 1977 left Dunshay unconditionally to charity. This is not consistent with Dunshay being the (or a) joint home of Margot or Mary. They did not in any real sense live under the same roof. They were physically together for one weekend in two and for an occasional longer period; but for the last 20 years or more, not for longer than 2 weeks. Mrs Biddulph, who knew Mary well and saw her every day over the summer of 2005, described her as ‘incredibly lonely’, which does not suggest two people living together. Those who knew them best spoke of Mary going to ‘stay’ with or ‘visit’ Margot and vice versa. That, in my judgment, was the reality. They each had their own home. Moreover, for the last 2 years of Mary’s life (which is the period that the Act requires me to concentrate on) Margot had to have 24-hour care, which made it virtually impossible for her to go to Dunshay. She did not in fact go to Dunshay after 2003. Her domestic economy was managed by Nigel. However, there is no doubt that the centre of Mary’s life was Dunshay. That was her household and I do not consider that it can be said that, for the last 2 years of her life, Margot lived in that household. Nor do I consider that it can be said that Mary lived in Margot’s household. She was, in my judgment, no more than a visitor. To borrow His Honour Judge 23 Norris’ phrase, there were two separate establishments and two separate domestic economies. [150] Accordingly, whether or not it can be said that Mary and Margot lived as civil partners, I hold that Margot’s claim under s 1(1B) fails. But in any event the true nature of the relationship between Margot and Mary was unacknowledged and, indeed, hidden. Some close members of the family knew of their relationship and other people guessed. But there were many people, including people who knew Mary well, who had no inkling. It seems to me that it is not possible to establish that two persons have lived together as civil partners unless their relationship as a couple is an acknowledged one. Indeed, it may be that an acknowledgement of the relationship is also an ingredient of living in the same household, which would only reinforce my conclusion that Mary and Margot did not live in the same household during the last 2 years of Mary’s life.” Any person (not being included within the foregoing paragraphs of subsection 1(1)) who immediately before the death of the deceased was being maintained either wholly or partly by the deceased [section 1(1)(e)] 40. Section 1(3) of the 1975 Act provides: “For the purposes of subsection 1(1)(e) above, a person shall be treated as being maintained by the deceased, either wholly or partly, as the case may be, if the deceased, otherwise than for full valuable consideration, was making a substantial contribution in money or money’s worth towards the reasonable needs of that person.” 41. Although section 1(1)(e) only applies to applicants who do not fit in with any of the other categories of claimant, it is not unusual for a claimant to claim under section 1(1)(e) in the alternative – see for example, Lindop –v- Agus above. A common sense and factual approach is taken to answering the question: was the applicant being maintained by the deceased immediately before death. 24 42. The leading cases are Re Beaumont [1980] Ch 444 (Sir Robert Megarry V-C) and Jelley –v- Iliffe [1981] Fam 128. Both concerned claims by heterosexual cohabitees and would now fall within section 1(1A). They remain of relevance in cases where the applicant was not in a cohabiting relationship with the deceased. Stephenson LJ in Jelley –v- Iliffe (agreeing with Sir Robert Megarry V-C) said: “(1) The deeming provision in s.1(3) exhaustively or exclusively defines what s.1(1)(e) means by “being maintained” and does not include in those words a state of affairs which is not within s. 1(3) and would extend its ambit. To qualify within s.1(1)(e) a claimant must satisfy s.1(3), as if before the words “if the deceased” the draftsman of s.1(3) had inserted the word “only”; (2) in considering whether a person is being maintained “immediately before the death of the deceased” it is the settled basis or general arrangement between the parties as regards maintenance during the lifetime of the deceased which has to be looked at, not the actual, perhaps fluctuating variation of it which exists immediately before his or her death. It is, I think, not disputed that a relationship of dependence which has persisted for years will not be defeated by its termination during a few weeks of mortal sickness; (3) Like the ViceChancellor I reject the contention that the parenthetical words in s.1(3) “otherwise than for full valuable consideration” apply only to full valuable consideration under a contract and agree with him and Mr Justice Arnold11 that they apply whenever full valuable consideration is given, whether under contract or otherwise.” 43. In Re Beaumont the Vice-Chancellor said, on the basis of s.3(4) of the Act that there had to be an assumption of responsibility by the deceased for the dependence of the claimant. The Court of Appeal in Jelley –v- Iliffe disagreed. Per Stephenson LJ: “I would not disagree with the Vice-Chancellor when he says that “the word `assumes’ ... seems to me to indicate that there must be some act or acts which demonstrate an undertaking of responsibility, or the taking of the responsibility 11 In Re Wilkinson (1978) Fam 22 25 on oneself”. And the Act, here and elsewhere, has drawn a distinction between assuming and discharging responsibility. But how better or more clearly can one take on or discharge responsibility for maintenance than by actually maintaining? A man may say he is going to support another and not do it, promise to pay school fees but not pay; but if he does pay them, has he not both assumed and discharged responsibility for them whether or not he covenants to pay them.” 44. As indicated earlier the case of Baynes –v- Hedger involved both a claim based upon a same sex cohabitation (by Margot) and a claim based upon s.1(1)(e) brought by Margot’s daughter. Lewison J had held that Margot’s daughter was being partly maintained by the deceased. The Court of Appeal disagreed because there had been no assumption of responsibility by the deceased for the claimant. When considering an application under s. 1(1)(e) the court was required, by s 3(4), to have regard to the extent to which and the basis upon which the deceased had assumed responsibility for the maintenance of the applicant, and to the length of time for which the deceased had discharged that responsibility. In deciding that the goddaughter was eligible to bring a claim, the judge had failed to consider, at the appropriate stage, the question whether the deceased had assumed responsibility for the goddaughter’s maintenance. The judge had, in fact, gone on to decide that the deceased had not assumed such responsibility when considering whether the deceased had made reasonable provision for the goddaughter in her will. The judge should have recognised that, given his conclusion on this point, the goddaughter was not eligible to bring a claim under s 1(1)(e), or at all, and he should have dismissed her claim on that basis. 45. The Law Commission has provisionally proposed that an assumption of responsibility by the deceased should not be a threshold requirement for an applicant to qualify to apply for family provision as a dependant under section 1(1)(e), but should be regarded on an equal footing with other factors. “Maintenance” in the context of s.1(1)(e) 26 46. See the Court of Appeal in Re Coventry [1980] Ch 461 at 484, 485: “So that whatever be the precise meaning of the word “maintenance” – and I do not think it is necessary to attempt any precise definition – it is clear that it is a word of somewhat limited meaning in its application to any person qualified to apply, other than a husband or a wife. There have been a number of cases under the Inheritance (Family Provision) Act 1938 previously in force, and also cases from sister jurisdictions, which have dealt with the meaning of “maintenance”. In particular, in this country there is Re E, E v- E [1966] 2 AER 44, [1966] 1 WLR 709 in which Stamp J said that the purpose was not to keep a person above the breadline but to provide reasonable maintenance in all the circumstances. If I may so with respect, “breadline” there would be more accurately described as “subsistence level”. Then there was Millward –v- Shenton [1972] AER 1025, [1972] 1 WLR 7111, CA in this court. I think I need only refer to one of the overseas reports, Re Duranceau [1952] 3 DLR 714, 720, where, in somewhat poetic language, the court said that the question is: “Is the provision sufficient to enable the dependant to live neither luxuriously nor miserably, but decently and comfortably according to his or her station in life?12” What is proper maintenance must in all cases depend upon all the facts and circumstances of the particular case being considered at the time, but I think it is 12 Note that in Graham –v- Murphy [1997] 1 FLR 860 at 869D Robert Walker J stated that he “did not find it helpful to reflect on an applicant’s station in life”. See also Goff LJ in Re Coventry [1980] Ch 461 at 485D “maintenance” is somewhere between “not just enough to enable a person to get by; on the other hand it does not mean anything which may be regarded as reasonably desirable for [the applicant’s] general benefit or welfare.” 27 clear on the one hand that one must not put too limited a meaning on it; it does not mean just enough to enable a person to get by; on the other hand it does not mean anything which may be regarded as reasonably desirable for his general benefit or welfare.” 47. In Re Jennings [1994] 1 FLR 536 “maintenance” was said to connote only those payments which would directly or indirectly enable the applicant to discharge the cost of his daily living; the provision to be made, albeit it may be by way of a lump sum, being to meet recurring expenses of living of an income nature. In Webster –v- Webster [2009] 1 FLR 1240 it was held13 that “maintenance” meant “maintenance in the context of [the applicant’s’ lifestyle as it was with [the deceased] Substantial contribution towards the claimant’s reasonable needs 48. One must assess the claim in the round. A “balance sheet” approach is not appropriate. Needs must be looked at from the perspective of s.3(1)(a) to (c) and – see Harrington –v- Gill (1983) 4 FLR 265 – “reasonable needs” may mean “reasonable requirements”. 49. The Law Commission provisionally proposes that it should not longer be a prequisite to the success of a claim under the 1975 Act brought by a dependant that the deceased contributed substantially more to the relationship than did the claimant. Matters to which the Court is to have regard when exercising its powers – section 3 50. Section 3(1) of the 1975 Act provides that where an application is made for an order under s 2 of the Act, the court must, in determining whether the disposition of the deceased’s estate effected by his Will or the law relating to intestacy, or the combination of the Will and that law, is such as to make reasonable financial 13 See Negus –v- Bahouse [2008] 1 FLR 381 28 provision for the applicant and, if the court considers that reasonable financial provision has not been made, in determining whether and in what manner it shall exercise its powers under that section, have regard to the following matters (as at the date of the hearing14: s 3(5)), that is to say: (i) the financial resources (including earning capacity: s 3(6)) and financial needs (including financial obligations and responsibilities: s 3(6)) which the applicant has or is likely to have in the foreseeable future: s 3(1)(a); (ii) the financial resources (including earning capacity: s 3(6)) and financial needs (including financial obligations and responsibilities: s 3(6)) which any other applicant for an order under s 2 of the Act has or is likely to have in the foreseeable future: s 3(1)(b); (iii) the financial resources (including earning capacity in s 3(6)) and financial needs (including financial obligations and responsibilities: s 3(6)) which any beneficiary of the estate of the deceased has or is likely to have in the foreseeable future: s 3(1)(c); (iv) any obligations and responsibilities which the deceased had towards any applicant for an order under s 2 or towards any beneficiary of the estate of the deceased: s 3(1)(d)15; (v) the size and nature of the net estate of the deceased: s 3(1)(e)16; 14 See Re Hancock [1998] 2 FLR 346, CA (an estate acquired a substantial windfall of capital between the death of the deceased and the date of the hearing; held, the court must assess the relevant criteria both for the purpose of deciding whether the disposition of the estate fails to make reasonable financial provision for the applicant and the subsequent issue of the award necessary to make such provision on the basis of the facts as it finds them to be at the date of the hearing. However, delay is a factor which may be taken into account as one of the relevant circumstances under s 3(1)(g) 15 Re Jennings [1994] 1 FLR 536, CA. 29 (vi) any physical or mental disability of any applicant for an order under s 2 or any beneficiary of the estate of the deceased: s 3(1)(f)17; (vii) any other matter, including the conduct of the applicant or any other person, which in the circumstances of the case the court may consider relevant: s 3(1)(g)18; (viii) when the application is made by a person who lived with the deceased as husband or wife or civil partner for two years or more before death pursuant to the 1975 Act s 1(1)(ba) as amended by the LR(S)A 1995, s 2, the age of the applicant and the length of time they lived together as husband and wife or civil partners and the contribution made by the applicant to the welfare of the family of the deceased, including any contribution made by looking after the home or caring for the family19; (ix) other matters in relation to a claim by a spouse, former spouse, civil partner or former civil partner as set out at section 3(2) (x) other matters in relation to a claim by a child of the deceased or a child treated by the deceased as a child of the family20; 16 The court is entitled to look at the whole estate including foreign real property: see Bheekhun –v- Williams [1999] 2 FLR 229, CA. 17 See Hanbury –v- Hanbury [1999] 2 FLR 255 where applicant suffered gravely from effects of premature birth; see also Re Debenham [1986] 1 FLR 404 where the 58 year old applicant was incapable of work and suffered from severe epilepsy. “Mere” old age may not qualify as ill-health see Barrass –v- Harding [2001] 1 FLR 138 – 79 year old former wife in ill health. Claim failed. Note that her ancillary relief claims had been dismissed by consent in 1965 18 Compare MCA 1973, s25 and note the difference in the wording as to “conduct”. See Re Snoek [2983] Fam Law 383 where “atrocious and vicious behaviour” led to a reduced award. See also Gandhi –v- Patel [2002] 1 FLR 603, and Baynes –v- Hedger [2008] 2 FLR 1805 19 S 3(2A) of the 1975 Act, inserted by the LR(S)A, s 2(4) and as amended by the CPA 2004, s 71, Sch 4, Pt 2, 20 Section 3(3) of the 1975 Act. 30 (xi) other matters in relation to a claim by a person maintained by the deceased immediately before his death21 as set out section 3(4). 51. There is no hierarchy amongst the factors within section 3(1). However, the size and nature of the estate and the current and foreseeable needs of the applicant and any other beneficiaries / applicants are likely to be central to the court’s deliberations. 52. When considering the section 3(1) factors the question of “moral obligation” frequently arises. In other words, did the deceased owe a moral obligation to the applicant. “Moral obligation” is not specifically mentioned within the statute. It arises primarily in the case of adult able-bodied children although it can also arise in the case of former spouses. Oliver J in Re Coventry [1980] Ch 461 concluded that the test as to whether or not there was an obligation on the part of the deceased was an objective one. The Court of Appeal agreed. The morality of the claim did not amount to a threshold test. The question remained: did the deceased make reasonable financial provision for the applicant within the terms of the Act22. 53. This lecture is limited primarily to considering the position of spouses, cohabitants and those who have been dependent upon the deceased. There is insufficient time and space to deal adequately with the position of children (minor and adult). However, there is a very important recent case, not yet fully reported which considers the position of an adult child as claimant and, also, the section 3(1) factors. It is Ilott –v- Mitson & Others [2011] EWCA Civ 346 decided on 31st March 2011. The case, according to the Court of Appeal was primarily concerned with the “threshold test” as to whether or not the deceased had made reasonable financial provision for the applicant. In this case the applicant was the adult (aged 50) estranged daughter of the deceased living in 21 Section 3(4() of the 1975 Act. See also Re Debenham (Deceased) [1986] 1 FLR 404, Re Leach [1984] FLR 590, Williams –v- Johns [1988] 2 FLR 475, Goodchild –v- Goodchild [1997] 2 FLR 644, Re Hancock [1998] 2 FLR 346, Espinosa –v- Bourke [1999] 1 FLR 747, Re Abram [1996] 2 FLR 379, Robinson –v- Fernsby (Re Scott Kilvert) [2003] EWCA Civ 1820; Cameron – v- Treasury Solicitor [1996] 2 FLR 716 22 31 modest circumstances with her five children who had been left nothing from her mother’s modest estate. DJ Million (as he then was) found that the will did not make reasonable financial provision and awarded her a lump sum of £50,000. Eleanor King J disagreed and accepted the argument of the charitable beneficiaries that it was reasonable to leave the daughter nothing. The Court of Appeal disagreed with King J and reinstated the decision of DJ Million. 54. Black LJ said: 88. A dispassionate study of each of the matters set out in section 3(1) will not provide the answer to the question whether the will makes reasonable financial provision for the applicant, no matter how thorough and careful it is. As Judge LJ said in Re Hancock at 355C, section 3 provides no guidance about the relative importance to be attached to each of the relevant criteria. So between the dispassionate study and the answer to the first question lies the value judgment to which the authorities have referred. It seems to me that the jurisprudence reveals a struggle to articulate, for the benefit of the parties in the particular case and of practitioners, how that value judgment has been, or should be, made on a given set of facts. Inevitably, this has led to statements that this or that matter is not enough to found a claim and this or that matter is required. 89. Mere financial need has been one of those matters rejected at times as not enough. Oliver J remarked in Re Coventry (476D), in a passage which found approval in the Court of Appeal, that: "the mere fact that the plaintiff finds himself in necessitous circumstances cannot, in my judgment, by itself render it unreasonable that no provision has, in the events which have happened, been made for his maintenance out of the deceased's estate." 90. This sentiment can be found reflected in other authorities, including in Espinosa v Bourke which has the distinction of being the most recent Court of Appeal authority on the Act to which we were taken in argument and which includes the following endorsement in the judgment of Butler-Sloss LJ: "As Oliver J pointed out in Re Coventry, necessitous circumstances cannot be in themselves the reason to alter the testator's dispositions. " 91. A close analysis of the authorities reveals, however, that a bald statement of that kind can be misleading if taken out of context. Necessitous circumstances will never actually be the sole factor from amongst the section 3(1) list to feature in a case. 32 o The size and nature of the estate (section 3(1)(e)) will always be material. o Consideration will always have to be given to the situation of any other beneficiary of the estate (section 3(1)(c)) because the proceedings would not exist if there were not at least one such beneficiary. It was said in Cameron v Treasury Solicitor that the devolution of the estate to the Crown could not enhance the applicant's claim and was a neutral factor, not relevant to the criteria to be taken into account under section 3, but I do confess to some difficulty with that approach because, if the presence of a needy beneficiary has the potential to weaken the applicant's claim (as it must have where the estate is limited), so must the absence of any beneficiary in the conventional sort of need have the potential to assist the applicant. I suspect that it may be an approach which should be seen in the light of the facts of that particular case in which the applicant had the fundamental difficulty that she had been divorced from the deceased 19 years before he died and a clean break order had been made in ancillary relief proceedings; one can see why, therefore, the fact that the estate devolved to the Crown as bona vacantia was not of assistance to her in establishing her claim. o Section 3(1)(g), drafted as it is in very broad terms, may well draw in other factors depending on the facts of the individual case, amongst them potentially the views of the deceased. Goff LJ said in Re Coventry [488H] that a view expressed by a deceased person that he wishes a particular person to benefit will generally be of little significance, because the question is not subjective but objective, but that an express reason for rejecting the applicant is a different matter and may be very relevant to the problem. Butler-Sloss LJ said in Re Hancock (supra): "A good reason to exclude a member of the family has to be a relevant consideration. However, in my view, the recognition by a testator of the status of members of his family and his goodwill towards them and in this case towards the plaintiff are factors which it is proper to take into account under s 3(1)(g) and it is for the court to give such weight to those factors as may in the individual case be appropriate." [352E] 92. The search for the elusive feature which tips the balance in favour of this claimant and not in favour of that has concentrated on two candidates in particular, moral obligation and special circumstances. Despite the fact that the Court of Appeal said in Re Coventry that Oliver J had not made moral obligation a pre-requisite and nor did they, moral obligation continued to feature in subsequent decisions, albeit perhaps as a sub-species of special circumstances. For example, in In re Jennings Nourse LJ said that it had been established that 33 "on an application by an adult son of the deceased who is able to earn, and earns, his own living there must be some special circumstance, typically a moral obligation of the deceased towards him, before the first question can be determined in his favour" [295F] 93. Nourse LJ later moderated this in Re Pearce (supra), considering that Re Hancock had demonstrated that "the principle is not to be stated in such seemingly absolute terms. There is no invariable prerequisite that a moral obligation or some other special circumstances must be shown….." [710D] 94. Re Hancock is, in my view, an important decision. I will not rehearse the passages from it which the President has cited in his judgment. As Nourse LJ said, the court rejected the idea that a moral claim or special circumstances were necessarily required (or, per Sir John Knox at 358B, that there is any "single essential factor for the success or failure of an application under the Act") although they recognised that there may be factual situations such as in Re Coventry and, even more so in Re Jennings, in which something of that sort would be required to persuade the court that the scales tipped in favour of the applicant. Sir John Knox's treatment (in the passage quoted by the President) of the process of evaluation of a claim under the Act is particularly helpful in reminding us of the right way to approach the present class of case under the Act, as Butler-Sloss LJ said in Espinosa v Bourke at 755H. 95. One of the things that I draw from Re Hancock as a whole is the importance of having recourse directly to the words of the statute itself. The courts have said that it is inappropriate to put a gloss on those words. Peter Gibson LJ said so in relation to the assertion that the applicant must have a moral claim in order to succeed, see Cameron v Treasury Solicitor [722B]. Butler-Sloss LJ said in Espinosa v Bourke [755F] that "[f]rom the judgments of this court in Re Coventry to the present day, it should be clear that no gloss has been put upon subsection (1)(d)". Whilst these passages revolve around section 3(1)(d), it is surely equally unacceptable to put a gloss on any other part of the relevant sections of the Act. 96. Mr Harrap's submissions seem to me to be an invitation to us to embellish the words of the statute and amount, in my view, to an impermissible attempt to prescribe the exercise that has to be carried out in this sort of case by requiring the application of a principle of some kind in addition to the plain words of the statute itself. 97. Contrary to his submissions, an adult child of the deceased is: "in no different position from any other applicant who has to prove his case. The court has to have regard to s 3(1)((a)-(g) and assess the relevance and weight to be given to each factor in the list." Espinosa v Bourke [755F] 34 98. Each case depends upon its own facts and upon how the judge strikes the balance between the section 3(1) factors in first answering the question whether reasonable financial provision has been made for the applicant and then determining what order to make. That is clear throughout the line of authorities from Re Coventry onwards. The following passages are examples only of what has been said: "In every case, inevitably it is going to be a matter of degree…. ….In the end, to my mind Oliver J struck a balance and reached a conclusion which I find it impossible to fault…" Re Coventry [493D and G] "A judge making a decision at the first stage, although he does not exercise a discretion, does make a value judgment based upon balancing the factors set out in s 3 of the 1975 Act." Re Hancock [353H] "In the great majority of contested applications the court is involved in a balancing exercise among the many factors to which s 3 of the 1975 Act requires the court to have regard. Some factors may be neutral but many will go in the scales either in favour of or against the proposition that there has been a failure to make reasonable financial provision for the applicant." ibid [357A] "Section 3(1) of the 1975 Act sets out the matters to which the court has to have regard. It is a complete list…… The task of the court is that required by s 3 of the Act. It is therefore incumbent upon the court to consider all the matters referred to in subsection (1) of that section…." Espinosa v Bourke [760D] 55. See also Cattle –v- Evans[2011] 2 FLR 843 for an illustration of the court taking into account the section 3 factors. Costs 56. It is worthwhile to mention costs. There is a myth that in family provision cases either (a) the no order as to costs rule applies or (b) everyone’s costs will come out of the estate at the end of the day. This is wrong! These are CPR proceedings and consideration must be given to Part 36 of the CPR. Costs generally follow the event (see CPR r.44.3(2)(a)) and the losing party generally pays the costs. In Re Fullard [1982] Fam 42 Ormrod LJ said: 35 “Where the estate, like this one, is small, in my view the onus on an applicant of satisfying the conditions in section 2 is very heavy indeed and these applications ought not to be launched unless there is (or appears to be) a real chance of success, because the result of these proceedings simply diminishes the estate and is a great hardship on the beneficiaries if there are ultimately successful in the litigation. For that reason I would be disposed to think that judges should reconsider the practice of ordering the costs of both sides out of the estate. That is probate litigation; this is something quite different. I think judges should look very closely indeed at the merits of each application before ordering that the estate pays the applicant’s costs if the applicant is unsuccessful.” 57. Under the CPR a failure to follow the protocols or to make Part 36 offers (or a failure to beat a Part 36 offer) will all be relevant when the court comes to consider costs John Wilson QC 1, Hare Court, Temple, EC4Y 7BE 3rd November 2011 36