Word

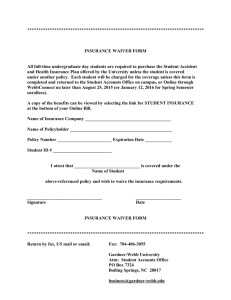

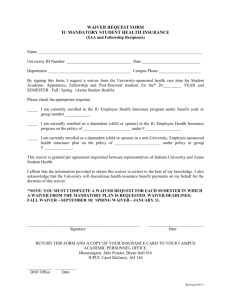

advertisement