updates in civil procedure and special proceedings

advertisement

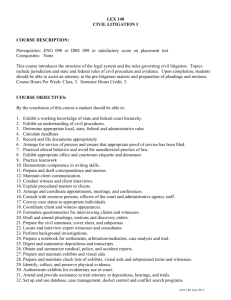

UPDATES IN CIVIL PROCEDURE AND SPECIAL PROCEEDINGS - Outline Justice Magdangal M. de Leon CIVIL PROCEDURE What is civil procedure? The method of conducting a judicial proceeding to resolve disputes involving private parties for the purpose of enforcing private rights or obtaining redress for the invasion of rights. May a procedural rule be given retroactive effect? Yes, inasmuch as there are no vested rights in rules of procedure. The fresh 15-day period (decreed in Neypes vs. CA) within which to file notice of appeal counted from notice of the denial of the motion for reconsideration may be applied to petitioners’ case inasmuch as rules of procedure may be given retroactive effect to actions pending and undetermined at the time of their passage. (Sumaway vs. Urban Bank, Inc., 493 SCRA 99 [June 27, 2006]). STAGES IN CIVIL PROCEDURE I. BEFORE FILING 0F THE ACTION A. Actions in general 1. Cause of action 2. Right of action B. Parties 1. Parties in general 2. Kinds of parties 3. Requirements a. legal capacity b. real party in interest c. standing to sue 4. Joinder of parties a. joinder of initial parties 1) compulsory 2) permissive b. third (fourth, etc.) party c. special joinder modes 1) class suit 2) intervention 3) interpleader C. Referral to barangay conciliation D. Selection of court 1. Kinds of civil actions a. Ordinary and special b. Personal, real c. In personam, in rem, quasi-in rem d. Local and transitory 2. Hierarchy of courts 3. Jurisdiction 4. Venue 5. Summary procedure E. Pleadings, motions and notice 1. Pleadings in general -2a. Formal requirements 1) Verification 2) Certification of non-forum shopping b. Manner of making allegations in pleadings 2. Complaint a. Joinder of causes of action 1) Permissive 2) Compulsory 3. Filing and service of pleadings and other papers II. FILING OF THE ACTION A. Commencement of the action B. Docket fees C. Raffle of cases D. Provisional remedies, if necessary III. COURT ACQUIRES JURISDICTION OVER THE PARTIES A. Summons 1. Modes of Service of Summons a. personal service b. substituted service c. constructive service (by publication) d. extraterritorial service B. Voluntary appearance IV. INCIDENTS AFTER COURT ACQUIRES JURISDICTION OVER THE PARTIES A. Plaintiff’s notice and motions 1. notice of dismissal of the complaint under Rule 17, Section 1 2. amended complaint under Rule 10, Section 2 3. motion for leave to file a supplemental complaint under Rule 10, Section 6 4. motion to declare defendant in default under Rule 9, Section 3 B. Defendant’s motions 1. motion to set aside order of default under Rule 9, Section 3 2. motion for extension of time to file responsive pleading under Rule 11, Section 11 3. motion for bill of particulars under Rule 12 4. motion to dismiss complaint under Rule 16 V. JOINDER OF ISSUES A. Plaintiff’s motions and pleadings 1. Motions a. To dismiss complaint under Rule 17, Sec. 2 b. To amend or supplement complaint under Rule 17, Secs. 3 and 6 c. For judgment on the pleadings under Rule 34 e. For summary judgment under Rule 35 f. To set pre-trial 2. Pleadings a. Reply b. Answer to counterclaim 3. Others a. Pre-trial brief B. Defendant’s motion and pleading 1. Motion a. Motion to dismiss complaint due to fault of plaintiff under Rule 17, Sec. 3 -32. Pleading a. Answer with or without counterclaim 3. Others a. Pre-trial brief VI. PRE-TRIAL A. Plaintiff’s motions 1. To present evidence ex parte and render judgment B. Defendant’s motion 1. Motion to dismiss C. Common motions 1. To postpone 2. For consolidation or severance 3 For trial by commissioner D. Joinder 1. Joinder of claims or causes of action 2. Joinder of parties VII. DEPOSITIONS AND DISCOVERY A. Depositions B. Interrogatories to parties C. Admission by adverse party D. Production or inspections of documents or things E. Physical and mental examination of persons VIII. TRIAL A. Amendment to conform to or authorize presentation of evidence under Rule 10, Sec. 5 IX. AFTER TRIAL BUT BEFORE JUDGMENT A. Common motion 1. To submit memorandum B. Defendant’s motion 1. For judgment on demurrer to evidence X. JUDGMENT XI. AFTER JUDGMENT A. Common motions 1. For reconsideration 2. For new trial XII. APPEAL AND REVIEW A. Before finality 1. Ordinary appeal 2. Petition for review 3. Petition for review on certiorari B. After finality 1. Petition for certiorari 2. Petition for relief from judgment 3. Petition for annulment of judgment XIII. EXECUTION AND SATISFACTION OF JUDGMENT A. In general 1. Kinds of execution a. Mandatory -4b. Discretionary B. Procedure for execution 1. In case of death of party 2. Of judgments for money 3. Of judgments for specific act 4. Of special judgments C. Execution sales 1. Sales on execution 2. Conveyance of property sold on execution 3. Redemption of property sold on execution E. Satisfaction of judgment XIII. SPECIAL CIVIL ACTIONS ACTIONS IN GENERAL Basic rule in filing of action (Rule 2, Secs. 3-4) 1. For one cause of action (one delict or wrong), file only ONE ACTION or suit. Generally, NO SPLITTING A SINGLE CAUSE OF ACTION. Reasons: a. to avoid multiplicity of suits; b. to minimize expenses, inconvenience and harassment. 2. Remedy against splitting a single cause of action (two complaints separately filed for one action) - defendant may file: a. motion to dismiss on the ground of (1) litis pendentia, if first complaint is still pending (Rule 16, Sec. 1 [e]) (2) res judicata, if first complaint is terminated by final judgment (Rule 16, Sec. 1 [f]) b. answer alleging either of above grounds as affirmative defense (Rule 16, Sec. 6) If defendant fails to raise ground on time, he is deemed to have WAIVED them. Splitting must be questioned in the trial court; cannot be raised for the first time on appeal. What are the requisites for joinder of causes of action? (Rule 2, Sec. 5) 1. Compliance with the rules on joinder of parties under Rule 3, Sec. 6. 2. A party cannot join in an ordinary action any of the special civil actions. – Reason: special civil actions are governed by special rules. 3. Where the causes of action are between the SAME PARTIES but pertain to DIFFERENT VENUES OR JURISDICTIONS, the joinder may be allowed in the RTC, provided ONE OF THE CAUSES OF ACTION falls within the jurisdiction of the RTC and the venue lies therein. Exception: ejectment case may not be joined with an action within the jurisdiction of the RTC as the same comes within the exclusive jurisdiction of the MTC. However, if a party invokes the jurisdiction of the court, he cannot thereafter challenge the court’s jurisdiction in the same case. He is barred by estoppel from doing so. (Hinog vs. Melicor, G.R. No. 140954, April 12, 2005) N.B. As to joinder in the MTC, it must have jurisdiction over ALL THE CAUSES OF ACTION and must have common venue. 4. Where the claims in all the causes of action are principally for recovery of money, jurisdiction is determined by the AGGREGATE OR TOTAL AMOUNT claimed (totality rule). N.B. The totality rule applies only to the MTC – totality of claims cannot exceed the jurisdictional amount of the MTC. -5There is no totality rule for the RTC because its jurisdictional amount is without limit. Exc. In tax cases where the limit is below P1 million. Amounts of P1 million or more fall within the jurisdiction of the CTA. An ordinary civil action and petition for issuance of writ of possession may be consolidated. While a petition for a writ of possession is an ex parte proceeding, being made on a presumed right of ownership, when such presumed right of ownership is contested and is made the basis of another action, then the proceedings for writ of possession would also become groundless. The entire case must be litigated and if need must be consolidated with a related case so as to thresh out thoroughly all related issues. (PSB vs. Sps. Mañalac, Jr., G.R. No. 145441, April 26, 2005). PARTIES Lack of legal capacity to sue – plaintiff’s general disability to sue, such as on account of minority, insanity, incompetence, lack of juridical personality or any other general disqualifications of a party. Plaintiff’s lack of legal capacity to sue is a ground for motion to dismiss (Rule 16, Sec. 1[d}). Ex. A foreign corporation doing business without a license lacks legal capacity to sue. Lack of personality to sue – the fact that plaintiff is not the real party in interest. Plaintiff’s lack of personality to sue is a ground for a motion to dismiss based on the fact that the complaint, on its face, states no cause of action (Rule 16, Sec. 1 [g]) (Evangelista vs. Santiago, 457 SCRA 744 [2005]) In a case involving constitutional issues, “standing” or locus standi means a personal interest in the case such that the party has sustained or will sustained DIRECT INJURY as a result of the government act that is being challenged. To have legal standing, the petitioner must have DIRECT, PERSONAL and SUBSTANTIAL INTEREST to protect. Here, petitioners, retired COA Chairmen and Commissioners, have not shown any direct and personal interest in the COA Organizational Restructuring Plan. There is no indication that they have sustained or are in imminent danger of sustaining some direct injury as a result of its implementation. Clearly, they have no legal standing to file the instant suit (Domingo vs. Carague, 456 SCRA 450 [2005]). JOINDER OF PARTIES Procedure for dismissal if indispensable party is not impleaded a. The responsibility of impleading all the indispensable parties rests on the plaintiff. To avoid dismissal, the remedy is to implead the non-party claimed to be indispensable. b. If plaintiff REFUSES to implead an indispensable party despite the order of the court, the complaint may be dismissed upon motion of defendant or upon the court’s own motion. c. Only upon unjustified failure or refusal to obey the order to include is the action dismissed (Domingo vs. Scheer, 421 SCRA 468 [2004]). Whenever it appears to the court in the course of the proceeding that an indispensable party has not been joined, it is the duty of the court to STOP THE TRIAL and to ORDER THE INCLUSION of such party. The absence of an indispensable party renders all subsequent actuations of the court NULL and -6VOID, for want of authority to act, not only as to the absent parties, but even as to those present (Uy vs. CA, 494 SCRA 535 [July 11, 2006]). Intervention (Rule 19, Sec. 1) Under this Rule, intervention shall be allowed when a person has (1) a legal interest in the matter in litigation; (2) or in the success of any of the parties; (3) or an interest against the parties; (4) or when he is so situated as to be adversely affected by a distribution or disposition of property in the custody of the court or an officer thereof. (Alfelor vs. Halasan, G.R. No. 165987, March 31, 2006). Requirements: [a] legal interest in the matter in litigation; and [b] consideration must be given as to whether the adjudication of the original parties may be delayed or prejudiced, or whether the intervenor's rights may be protected in a separate proceeding or not. Legal interest must be of such DIRECT and IMMEDIATE character that the intervenor will either gain or lose by direct legal operation and effect of the judgment. Such interest must be actual, direct and material, and not simply contingent and expectant. (Perez vs. CA, G.R. No. 162580. January 27, 2006) The allowance or disallowance of a motion for leave to intervene and the admission of a complaint-in-intervention is addressed to the sound discretion of the trial court. The discretion of the court, once exercised, cannot be reviewed by certiorari save in instances where such discretion has been exercised in an arbitrary manner. (Angeles vs. Republic, G.R. No. 166281, October 27, 2006) What is the effect of non-substitution of a deceased party? Non-compliance with the rule on substitution would render the proceedings and judgment of the trial court infirm because the court acquires NO JURISDICTION over the persons of the legal representatives or of the heirs on whom the trial and the judgment would be binding. Thus, proper substitution of heirs must be effected for the trial court to acquire jurisdiction over their persons and to obviate any future claim by any heir that he was not apprised of the litigation against Bertuldo or that he did not authorize Atty. Petalcorin to represent him. No formal substitution of the parties was effected within thirty days from date of death of Bertuldo, as required by Section 16, Rule 3 of the Rules of Court. Needless to stress, the purpose behind the rule on substitution is the protection of the right of every party to due process. It is to ensure that the deceased party would continue to be properly represented in the suit through the duly appointed legal representative of his estate. (Hinog vs. Melicor, 455 SCRA 460 [2005]) The Rules require the legal representatives of a dead litigant to be substituted as parties to a litigation. This requirement is necessitated by due process. Thus, when the rights of the legal representatives of a decedent are actually recognized and protected, noncompliance or belated formal compliance with the Rules cannot affect the validity of the promulgated decision. After all, due process had thereby been satisfied. When a party to a pending action dies and the claim is not extinguished, the Rules of Court require a substitution of the deceased. The procedure is specifically governed by Section 16 of Rule 3. (Dela Cruz vs. Joaquin, G.R. No. 162788, July 28, 2005). -7SELECTION OF COURT What is hierarchy of courts? Pursuant to this doctrine, direct resort from the lower courts to the Supreme Court will not be entertained unless the appropriate remedy cannot be obtained in the lower tribunals. Rationale: (a) to prevent inordinate demands upon the SC’s time and attention which are better devoted to those matters within its exclusive jurisdiction, and (b) to prevent further overcrowding of the SC’s docket. Thus, although the SC, CA and the RTC have CONCURRRENT jurisdiction to issue writs of certiorari, prohibition, mandamus, quo warranto, habeas corpus and injunction, such concurrence does not give the petitioner unrestricted freedom of choice of court forum. The SC will NOT ENTERTAIN DIRECT RESORT to it unless the redress desired cannot be obtained in the appropriate courts, and EXCEPTIONAL AND COMPELLING CIRCUMSTANCES, such as cases of national interest and of serious implications, justify the extraordinary remedy of writ of certiorari, calling for the exercise of its primary jurisdiction. (Hinog vs. Melicor, 455 SCRA 460 [2005]) VENUE The venue of the action for the nullification of the foreclosure sale is properly laid with the Malolos RTC although two of the properties together with the Bulacan properties are situated in Nueva Ecija. The venue of real actions affecting properties found in different provinces is determined by the SINGULARITY or PLURALITY of the transactions involving said parcels of land. Where said parcels are the object of one and the same transaction, the venue is in the court of any of the provinces wherein a parcel of land is situated (United Overseas Bank Phils. (formerly Westmont Bank) vs. Rosemoore Mining & Development Corp., G.R. Nos. 159669 & 163521, March 12, 2007). PLEADINGS In what ways may forum shopping be committed? 1. Filing multiple cases based on the same cause of action and with the same prayer, the previous case not having been resolved yet (litis pendentia) 2. Filing multiple cases based on the same cause of action and the same prayer, the previous case having been finally resolved (res judicata) 3. Filing multiple cases based on the same cause of action but with different prayers (splitting causes of action) where the ground for dismissal is also either litis pendentia or res judicata. Effect of forum shopping 1. If the forum shopping is NOT considered WILFUL and DELIBERATE, the subsequent cases shall be DISMISSED WITHOUT PREJUDICE on one of the two grounds mentioned above 2. If the forum shopping is WILFUL and DELIBERATE, both (or all, if there are more than two actions) shall be DISMISSED WITH PREJUDICE (Ao-As vs. CA, 491 SCRA 353 [2006]) What are the requirements of forum shopping certificate for a corporation? Only individuals vested with authority by a valid board resolution may sign the certificate of non-forum shopping in behalf of a corporation. In addition, the Court has required that proof of said authority must be attached. Failure to provide a certificate of non-forum shopping is sufficient ground to dismiss the -8petition. Likewise, the petition is subject to dismissal if a certification was submitted unaccompanied by proof of the signatory's authority. (Philippine Airlines, Inc. vs. Flight Attendants and Stewards Association of the Philippines (FASAP), G.R. No. 143088. January 24, 2006) However, subsequent submission of Secretary’s Certificate is substantial compliance with the requirement that a Board Resolution must authorize the officer executing the non-forum certification on behalf of the corporation. (International Construction Inc. vs. Feb Leasing and Financing Corp., G.R. No. 157195, April 22, 2005) Non-forum shopping certification is not required in a petition for issuance of writ of possession because it is not an initiatory pleading. The certification against forum shopping is required only in a complaint or other initiatory pleading. The ex-parte petition for the issuance of a writ of possession filed by the respondent is not an initiatory pleading. Although the private respondent denominated its pleading as a petition, it is, nonetheless, a motion. What distinguishes a motion from a petition or other pleading is not its form or the title given by the party executing it, but rather its purpose. The office of a motion is not to initiate new litigation, but to bring a material but incidental matter arising in the progress of the case in which the motion is filed. (Sps. Arquiza vs. Court of Appeals, et. al., G.R. No. 160479, June 8, 2005) Litis pendentia is not present between a petition for writ of possession and action for annulment of foreclosure. The issuance of the writ of possession being a ministerial function, and summary in nature, it cannot be said to be a judgment on the merits, but simply an incident in the transfer of title. Hence, a separate case for annulment of mortgage and foreclosure sale cannot be barred by litis pendentia or res judicata. Thus, insofar as Spec. Proc. No. 99-00988-D and Civil Case No. 99-03169-D pending before different branches of RTC Dagupan City are concerned, there is no litis pendentia. (Yu vs. PCIB, G.R. No. 147902. March 17, 2006) The pendency of a SEC case may be invoked as posing a prejudicial question to an RTC civil case. Since the determination of the SEC as to which of the two factions is the de jure board of NUI is crucial to the resolution of the case before the RTC, we find that the trial court should suspend its proceedings until the SEC comes out with its findings. (Abacan, Jr., et. al. vs. Northwestern University, Inc., G.R. No. 140777, April 8, 2005) What is judicial courtesy? There are instances where even if there is no writ of preliminary injunction or temporary restraining order issued by a higher court, it would be proper for a lower court or court of origin to suspend its proceedings on the precept of judicial courtesy. As the Supreme Court explained in Eternal Gardens Memorial Park v. Court of Appeals, 164 SCRA 421, 427-428 (1988): Due respect for the Supreme Court and practical and ethical considerations should have prompted the appellate court to wait for the final determination of the petition before taking cognizance of the case and trying to render moot exactly what was before this court x x x. This Court explained, however, that the rule on “judicial courtesy” applies where “there is a STRONG PROBABILITY that the issues before the higher court would be rendered MOOT AND MORIBUND as a result of the continuation of the proceedings in the lower court or court of origin.” (Republic vs. Sandigan, 492 SCRA 748 [June 26, 2006]) -9- A compulsory counterclaim does not require a certificate of non-forum shopping because a compulsory counterclaim is not an initiatory pleading. The Rule distinctly provides that the required certification against forum shopping is intended to cover an "initiatory pleading," meaning an "incipient application of a party asserting a claim for relief." Certainly, respondent bank's Answer with Counterclaim is a responsive pleading, filed merely to counter petitioners' complaint that initiates the civil action. In other words, the rule requiring such certification does not contemplate a defendant's/respondent's claim for relief that is derived only from, or is necessarily connected with, the main action or complaint. In fact, upon failure by the plaintiff to comply with such requirement, Section 5, quoted above, directs the "dismissal of the case without prejudice," not the dismissal of respondent's counterclaim. (Carpio vs. Rural Bank of Sto. Tomas (Batangas), Inc., G.R. No. 153171. May 4, 2006) What are the tests or criteria to determine compulsory or permissive nature of specific counterclaims? The criteria or tests by which the compulsory or permissive nature of specific counterclaims can be determined are as follows: 1. Are the issues of fact and law raised by the claim and counterclaim largely the same? 2. Would res judicata bar a subsequent suit on defendant’s claim absent the compulsory counterclaim rule? 3. Will substantially the same evidence support or refute plaintiff’s claim as well as defendant’s counterclaim? 4. Is there any logical relation between the claim and the counterclaim? The evidence of the petitioner on its claim in its complaint, and that of the respondents on their counterclaims are thus different. There is, likewise, no logical relation between the claim of the petitioner and the counterclaim of the respondents. Hence, the counterclaim of the respondents is an initiatory pleading, which requires the respondents to append thereto a certificate of nonforum shopping. Their failure to do so results to the dismissal of their counterclaim without prejudice. (Korea Exchange Bank vs. Hon. Gonzales, etc., et. al., G.R. Nos. 142286-87, April 15, 2005) A ground raised in a motion to dismiss may not be the subject of preliminary hearing as special and affirmative defense in the answer, except when there are several defendants but only one filed a motion to dismiss. Section 6, Rule 16 of the Rules of Court is explicit in stating that the defendant may reiterate any of the grounds for dismissal provided under Rule 16 of the Rules of Court as affirmative defenses but that a preliminary hearing may no longer be had thereon if a motion to dismiss had already been filed. This section, however, does not recontemplate a situation, such as the one obtaining in this case, except where there are several defendants but only one filed a motion to dismiss. (Abrajano vs. Salas, Jr., G.R. No. 158895. February 16, 2006) NOTICE OF DISMISSAL OF COMPLAINT under Rule 17, Sec. 1 The trial court has no discretion or option to deny the motion, since dismissal by the plaintiff under Section 1, Rule 17 is guaranteed as a matter of right to the plaintiffs. Even if the motion cites the most ridiculous of grounds for dismissal, - 10 the trial court has no choice but to consider the complaint as dismissed, since the plaintiff may opt for such dismissal as a matter of right, regardless of ground (O.B. Jovenir Construction and Development Corp. vs. Macamir Realty and CA, G.R. No. 135803, March 28, 2006). MOTION TO DISMISS COMPLAINT DUE TO PLAINTIFF’S FAULT under Rule 17, Sec. 3. Sec. 3, Rule 17 enumerates the instances where the complaint may be dismissed due to plaintiff’s fault: (1) if he fails to appear on the date for the presentation of his evidence in chief; (2) if he fails to prosecute his action for an unreasonable length of time; or (3) if he fails to comply with the rules or any order of the court. Once a case is dismissed for failure to prosecute, this has the effect of an adjudication on the merits and is understood to be with prejudice to the filing of another action unless otherwise provided in the order of dismissal. In other words, unless there be a qualification in the order of dismissal that it is without prejudice, the dismissal should be regarded as an adjudication on the merits and is with prejudice. (Cruz vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 164797, February 13, 2006) In situations contemplated in Section 3, Rule 17 of the Rules of Court, where a complaint is dismissed for failure of the plaintiff to comply with a lawful order of the court, such dismissal has the effect of an adjudication upon the merits. A dismissal for failure to prosecute has the effect of an adjudication on the merits, and operates as res judicata, particularly when the court did not direct that the dismissal was without prejudice. (Court of Appeals vs. Alvarez, G.R. No. 142439, December 3, 2006) Under Section 3, Rule 17 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, the dismissal of the complaint due to the fault of plaintiff does not necessarily carry with it the dismissal of the counterclaim, compulsory or otherwise. In fact, the dismissal of the complaint is without prejudice to the right of defendants to prosecute the counterclaim. (Pinga vs. Santiago, G.R. No. 170354, June 30, 2006). Remedy from order of dismissal for failure to prosecute – ordinary appeal. An order of dismissal for failure to prosecute has the effect of an adjudication on the merits. Petitioners’ counsel should have filed a notice of appeal with the appellate court within the reglementary period. Instead of filing a petition under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, the proper recourse was an ordinary appeal with the Court of Appeals under Rule 41. (Ko vs. PNB, 479 SCRA 298, January 20, 2006) Effect of declaration of default. The mere fact that a defendant is declared in default does not automatically result in the grant of the prayers of the plaintiff. To win, the latter must still present the same quantum of evidence that would be required if the defendant were still present. A party that defaults is not deprived of its rights, except the right to be heard and to present evidence to the trial court. If the evidence presented does not support a judgment for the plaintiff, the complaint should be dismissed, even if the defendant may not have been heard or allowed to present any countervailing evidence (Gajudo vs. Traders Royal Bank, G.R. No. 151098, March 21, 2006). A defendant party declared in default retains the right to appeal from the - 11 judgment by default on the ground that the plaintiff failed to prove the material allegations of the complaint, or that the decision is contrary to law, even without need of the prior filing of a motion to set aside the order of default (Martinez vs. Republic, G.R. No. 160895, October 30, 2006). Procedure trial court must take when a defendant fails to file an answer. Under Sec. 3 of Rule 9, the court "shall proceed to render judgment granting the claimant such relief as his pleading may warrant," subject to the court’s discretion on whether to require the presentation of evidence ex parte. The same provision also sets down guidelines on the nature and extent of the relief that may be granted. In particular, the court’s judgment "shall not exceed the amount or be different in kind from that prayed for nor award unliquidated damages." (Gajudo vs. Traders Royal Bank, supra) Amendment of a complaint may be allowed even if an order for its dismissal has been issued, as long as the motion to amend is filed before the dismissal order becomes final. The reason for allowing the amendment on this condition is that, upon finality of the dismissal, the court loses jurisdiction and control over the complaint. Thus, it can no longer make any disposition on the complaint in a manner inconsistent with the dismissal. After the order of dismissal without prejudice becomes final, and therefore falls outside the court’s power to modify, a party who wishes to reinstate the case has no remedy other than to file a new complaint. (Rodriguez Jr. vs. Aguilar, Sr., G.R. No. 159482, August 30, 2005) DISCOVERY PROCEDURES The importance of discovery procedures is well recognized by the Court. It approved A.M. No. 03-1-09-SC on July 13, 2004 which provided for the guidelines to be observed by trial court judges and clerks of court in the conduct of pre-trial and use of deposition-discovery measures. Under A.M. No. 03-1-09SC, trial courts are directed to issue orders requiring parties to avail of interrogatories to parties under Rule 25 and request for admission of adverse party under Rule 26 or at their discretion make use of depositions under Rule 23 or other measures under Rule 27 and 28 within 5 days from the filing of the answer. The parties are likewise required to submit, at least 3 days before the pre-trial, pre-trial briefs, containing among others a manifestation of the parties of their having availed or their intention to avail themselves of discovery procedures or referral to commissioners. (Hyatt Industrial Manufacturing Corp. vs. Ley Construction and Development Corp., G.R. No. 147143, March 10, 2006) JUDGMENT ON THE PLEADINGS Rule 34, Section 1 of the Rules of Court, provides that a judgment on the pleadings is proper when an answer fails to tender an issue or otherwise admits the material allegations of the adverse party's pleading. The essential question is whether there are issues generated by the pleadings. A judgment on the pleadings may be sought only by a claimant, who is the party seeking to recover upon a claim, counterclaim or cross-claim; or to obtain a declaratory relief. (Meneses vs. Secretary of Agrarian Reform, G.R. No. 156304, October 23, 2006) SUMMARY JUDGMENT - 12 - For summary judgment to be proper, two (2) requisites must concur, to wit: (1) there must be no genuine issue on any material fact, except for the amount of damages; and (2) the moving party must be entitled to a judgment as a matter of law. When, on their face, the pleadings tender a genuine issue, summary judgment is not proper. An issue is genuine if it requires the PRESENTATION OF EVIDENCE as distinguished from a sham, fictitious, contrived or false claim. The trial court’s decision was merely denominated as summary judgment. But in essence, it is actually equivalent to a judgment on the merits, making the rule on summary judgment inapplicable in this case. (Ontimare vs. Elep, G.R. No. 159224, January 20, 2006). When the facts as pleaded appear uncontested or undisputed, then there is no real or genuine issue or question as to the facts, and summary judgment is called for. The party who moves for summary judgment has the burden of demonstrating clearly the absence of any genuine issue of fact, or that the issue posed in the complaint is patently unsubstantial so as not to constitute a genuine issue for trial. Trial courts have limited authority to render summary judgments and may do so only when there is clearly no genuine issue as to any material fact. When the facts as pleaded by the parties are disputed or contested, proceedings for summary judgment cannot take the place of trial (Asian Construction and Development Corp. vs. PCIB, G.R. No. 153827, April 25, 2006). The trial court cannot motu proprio decide that summary judgment on an action is in order. Under the applicable provisions of Rule 35, the defending party or the claimant, as the case may be, must invoke the rule on summary judgment by filing a motion. The adverse party must be notified of the motion for summary judgment and furnished with supporting affidavits, depositions or admissions before hearing is conducted. More importantly, a summary judgment is permitted only if there is no genuine issue as to any material fact and a moving party is entitled to a judgment as a matter of law. (Pineda vs. Guevara, G.R. No. 143188, February 14, 2007). TRIAL Lack of cause of action may be cured by evidence presented during the trial and amendments to conform to the evidence. Amendments of pleadings are allowed under Rule 10 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure in order that the actual merits of a case may be determined in the most expeditious and inexpensive manner without regard to technicalities, and that all other matters included in the case may be determined in a single proceeding, thereby avoiding multiplicity of suits. Section 5 thereof applies to situations wherein evidence not within the issues raised in the pleadings is presented by the parties during the trial, and to conform to such evidence the pleadings are subsequently amended on motion of a party. (Swagman Hotels & Travel, Inc. vs. CA, G.R. No. 161135, April 8, 2005). DEMURRER TO EVIDENCE Upon the dismissal of the demurrer in the appellate court, the defendant loses the right to present his evidence and the appellate court shall then proceed to render judgment on the merits on the basis of plaintiff’s evidence. The rule, however, imposes the condition that if his demurrer is granted by the trial - 13 court, and the order of dismissal is reversed on appeal, the movant loses his right to present evidence in his behalf and he shall have been deemed to have elected to stand on the insufficiency of plaintiff’s case and evidence. In such event, the appellate court which reverses the order of dismissal shall proceed to render judgment on the merits on the basis of plaintiff’s evidence (Republic vs. Tuvera, G.R. No. 148246, February 16, 2007). Distinction between motion to dismiss for failure to state a cause of action, governed by Rule 16, Sec. 1 (g)) and motion to dismiss based on lack of cause of action, governed by Rule 33. A motion to dismiss based on lack of cause of action is filed by the defendant after the plaintiff has presented his evidence on the ground that the latter has shown no right to the relief sought. While a motion to dismiss under Rule 16 is based on preliminary objections which can be ventilated before the beginning of the trial, a motion to dismiss under Rule 33 is in the nature of a demurrer to evidence on the ground of insufficiency of evidence and is presented only after the plaintiff has rested his case (The Manila Banking Corp. vs. University of Baguio, Inc., G.R. No. 159189, February 21, 2007. APPEAL AND REVIEW The Supreme Court may review factual findings of the trial court and the Court of Appeals The petitioner admits that the issues on appeal are factual. Under Rule 45 of the Rules of Court, only questions of law may be raised, for the simple reason that the Court is not a trier of facts. The findings of the trial court as affirmed by the CA are conclusive on this Court, absent proof of any of the recognized exceptional circumstances such as: (1) the conclusion is grounded on speculations, surmises or conjectures; (2) the inference is manifestly mistaken, absurd or impossible; (3) there is grave abuse of discretion; (4) the judgment is based on a misapprehension of facts; (5) the findings of fact are conflicting; (6) there is no citation of specific evidence on which the factual findings are based; (7) the finding of absence of facts is contradicted by the presence of evidence on record; (8) the findings of the CA are contrary to those of the trial court; (9) the CA manifestly overlooked certain relevant and undisputed facts that, if properly considered, would justify a different conclusion; (10) the findings of the CA are beyond the issues of the case; and (11) the findings are contrary to the admissions of both parties. (Asian Construction & Dev’t. Corp. vs. Tulabut, G.R. No. 161904, April 26, 2005) We stress that regional trial courts have jurisdiction over complaints for recovery of ownership or accion reivindicatoria. Section 8, Rule 40 of the Rules on Civil Procedure nonetheless allows the RTC to decide the case brought on appeal from the MTC which, even without jurisdiction over the subject matter, may decide the case on the merits. In the instant case, the MTC of Mambajao should have dismissed the complaint outright for lack of jurisdiction but since it decided the case on its merits, the RTC rendered a decision based on the findings of the MTC. (Provost vs. CA, G.R. No. 160406, June 26, 2006). The RTC should have taken cognizance of the case. If the case is tried on the merits by the Municipal Court without jurisdiction over the subject matter, the RTC on appeal may no longer dismiss the case if it has original jurisdiction thereof. Moreover, the RTC shall no longer try the case on the merits, but shall decide the case on the basis of the evidence presented - 14 in the lower court, without prejudice to the admission of the amended pleadings and additional evidence in the interest of justice. (Encarnacion vs. Amigo, G.R. No. 169793, September 15, 2006). As the law now stands, inferior courts have jurisdiction to resolve questions of ownership whenever it is necessary to decide the question of possession in an ejectment case. Corollarily, the RTC erred when it agreed with the MTC’s decision to dismiss the case. At first glance, it appears that based on the P13,300.00 assessed value of the subject property as declared by respondents, the RTC would have no jurisdiction over the case. But the above-quoted provision refers to the original jurisdiction of the RTC. Section 22 of BP 129 vests upon the RTC the exercise of appellate jurisdiction over all cases decided by the Metropolitan Trial Courts, Municipal Trial Courts, and Municipal Circuit Trial Courts in their respective territorial jurisdictions. Clearly then, the amount involved is immaterial for purposes of the RTC’s appellate jurisdiction. All cases decided by the MTC are generally appealable to the RTC irrespective of the amount involved (Serrano vs. Gutierrez, G.R. No. 162366, November 10, 2006). Under Rule 40, full payment of the appellate docket fees within the prescribed period is mandatory, even jurisdictional. Otherwise, the appeal is deemed not perfected and the decision sought to be appealed from becomes final and executory. (Republic vs. Luriz, G.R. No. 158992, January 26, 2007). Appeal from RTC decision rendered in the exercise of its appellate jurisdiction – petition for review under Rule 42. Since the unlawful detainer case was filed with the MTC and affirmed by the RTC, petitioners should have filed a Petition for Review with the Court of Appeals under Rule 42 and not a Notice of Appeal with the RTC. However, we consider this to have been remedied by the timely filing of the Motion for Reconsideration on the following day. Section 3, Rule 50 of the Rules of Court allows the withdrawal of appeal at any time, as a matter of right, before the filing of the appellee’s brief. Applying this rule contextually, the filing of the Motion for Reconsideration may be deemed as an effective withdrawal of the defective Notice of Appeal. (Ross Rica Sales Center, Inc. vs. Ong, G.R. No. 132197, August 16, 2005) RELIEF FROM JUDGMENT Per Sec. 3, Rule 38, "The 60-day period is reckoned from the time the party acquired knowledge of the order, judgment or proceedings” and not from the date he actually read the same (Escueta vs. Lim, G.R. No. 137162, January 24, 2007). ANNULMENT OF JUDGMENT Rule 47 applies only to annulment by the Court of Appeals of judgments or final orders and resolutions in civil cases of Regional Trial Courts – it does not apply to criminal actions (People vs. Bitanga, G.R. No. 159222, June 26 2007); final judgments or orders of quasi-judicial tribunals or administrative bodies such as the National Labor Relations Commission, the Ombudsman, the Civil Service Commission, the Office of the President, and the PARAD (Fraginal vs. Paranal, G.R. No. 150207, February 223, 2007).; or to nullification of decisions of the Court of Appeals (Grande vs. University of the Philippines, G.R. No. 148456, September 15, 2006). - 15 EXECUTION Execution pending appeal applies to election cases. Despite the silence of the COMELEC Rules of Procedure as to the procedure of the issuance of a writ of execution pending appeal, there is no reason to dispute the COMELEC’s authority to do so, considering that the suppletory application of the Rules of Court is expressly authorized by Section 1, Rule 41 of the COMELEC Rules of Procedure which provides that absent any applicable provisions therein the pertinent provisions of the Rules of Court shall be applicable by analogy or in a suppletory character and effect. (Balajonda vs. COMELEC, G.R. No. 166032, February 28, 2005). When title has been consolidated in name of mortgagee, writ of possession is a matter of right. Once a mortgaged estate is extrajudicially sold, and is not redeemed within the reglementary period, no separate and independent action is necessary to obtain possession of the property. The purchaser at the public auction has only to file a petition for issuance of a writ of possession pursuant to Section 33 of Rule 39 of the Rules of Court. (DBP vs. Spouses Gatal, G.R. No. 138567, March 4, 2005). Execution of money judgments under Rule 39, Sec. 9 – promissory note not allowed. The law mandates that in the execution of a money judgment, the judgment debtor shall pay either in cash, certified bank check payable to the judgment obligee, or any other form of payment acceptable to the latter. Nowhere does the law mention promissory notes as a form of payment. The only exception is when such form of payment is acceptable to the judgment debtor. But it was obviously not acceptable to complainant, otherwise she would not have filed this case against respondent sheriff. In fact, she objected to it because the promissory notes of the defendants did not satisfy the money judgment in her favor. (Dagooc vs. Erlina, A.M. No. P-04-1857 (formerly OCA I.P.I. No. 02-1429-P), March 16, 2005) SPECIAL CIVIL ACTIONS Although the RTC has the authority to annul final judgments, such authority pertains only to final judgments rendered by inferior courts and quasijudicial bodies of equal ranking with such inferior courts. Given that DARAB decisions are appealable to the CA, the inevitable conclusion is that the DARAB is a co-equal body with the RTC and its decisions are beyond the RTC’s control (Springfield Development Corp. vs. Presiding Judge of RTC of Misamis Oriental, Branch 40, G.R. No. 142628, February 6, 2007). The writ of prohibition does not lie against the exercise of a quasilegislative function. Since in issuing the questioned IRR of R.A. No. 9207, the National Government Administration Committee was not exercising judicial, quasi-judicial or ministerial function, which is the scope of a petition for prohibition under Section 2, Rule 65 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, the instant prohibition should be dismissed outright. Where the principal relief sought is to invalidate an IRR, petitioners’ remedy is an ordinary action for its nullification, an action which properly falls under the jurisdiction of the Regional Trial Court. (Holy Spirit Homeowners Association vs. Defensor, G.R. No. 163980, August 3, 2006). - 16 A writ of mandamus commanding the respondents to require PUVs to use CNG is unavailing. Mandamus is available only to compel the doing of an act specifically enjoined by law as a duty. Here, there is no law that mandates the respondents LTFRB and the DOTC to order owners of motor vehicles to use CNG. At most the LTFRB has been tasked by E.O. No. 290 in par. 4.5 (ii), Section 4 “to grant preferential and exclusive Certificates of Public Convenience (CPC) or franchises to operators of NGVs based on the results of the DOTC surveys” (Henares, Jr. vs. Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board, G.R. No. 158290, October 23, 2006). Actions of quo warranto against persons who usurp an office in a corporation, which were formerly cognizable by the Securities and Exchange Commission under PD 902-A, have been transferred to the courts of general jurisdiction. But, this does not change the fact that Rule 66 of the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure does not apply to quo warranto cases against persons who usurp an office in a private corporation (Calleja vs. Panday, G.R. No. 168696. February 28, 2006). EXPROPRIATION Rep. Act No. 8974 mandates immediate payment of the initial just compensation prior to the issuance of the writ of possession in favor of the Government. Rep. Act No. 8974 represents a significant change from previous expropriation laws such as Rule 67, or even Section 19 of the Local Government Code. Rule 67 and the Local Government Code merely provided that the Government deposit the initial amounts antecedent to acquiring possession of the property with, respectively, an authorized Government depositary or the proper court. In both cases, the private owner does not receive compensation prior to the deprivation of property. Under the new modality prescribed by Rep. Act No. 8974, the private owner sees immediate monetary recompense with the same degree of speed as the taking of his/her property. (Republic vs. Gingoyon, G.R. No. 166429, December 19, 2005) Motion to dismiss is not permitted in a complaint for expropriation. Significantly, the Rule allowing a defendant in an expropriation case to file a motion to dismiss in lieu of an answer was amended by the 1997 Rules of Civil Procedure, which took effect on July 1, 1997. Section 3, Rule 67 now expressly mandates that any objection or defense to the taking of the property of a defendant must be set forth in an answer. (Masikip vs. City of Pasig, G.R. No. 136349. January 23, 2006) FORECLOSURE OF MORTGAGE A writ of possession is “a writ of execution employed to enforce a judgment to recover the possession of land. It commands the sheriff to enter the land and give possession of it to the person entitled under the judgment.” A writ of possession may be issued under the following instances: (1) in land registration proceedings under Section 17 of Act 496; (2) in a judicial foreclosure, provided the debtor is in possession of the mortgaged realty and no third person, not a party to the foreclosure suit, had intervened; (3) in an extrajudicial foreclosure of a real estate mortgage under Section 7 of Act No. 3135, as amended by Act No. 4118; and (4) in execution sales (last paragraph of Section 33, Rule 39 of the Rules of Court). The present case falls under the third instance. Under Section 7 of Act No. 3135, as amended by Act No. 4118, a writ of possession may be issued either - 17 (1) within the one-year redemption period, upon the filing of a bond, or (2) after the lapse of the redemption period, without need of a bond. (PNB vs. Sanao Marketing Corporation, G.R. No. 153951, July 29, 2005) A writ of preliminary injunction is issued to prevent an extrajudicial foreclosure, only upon a clear showing of a violation of the mortgagor’s unmistakable right. Unsubstantiated allegations of denial of due process and prematurity of a loan are not sufficient to defeat the mortgagee’s unmistakable right to an extrajudicial foreclosure. (Selegna Management and Development Corporation vs. UCPB, G.R. No. 165662, May 31, 2006) An action to invalidate the mortgage or the foreclosure sale is not a valid ground to oppose issuance of writ of possession. As a rule, any question regarding the validity of the mortgage or its foreclosure cannot be a legal ground for refusing the issuance of a writ of possession. Regardless of whether or not there is a pending suit for annulment of the mortgage or the foreclosure itself, the purchaser is entitled to a writ of possession, without prejudice of course to the eventual outcome of said case. (Sps. Arquiza vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 160479, June 8, 2005) FORCIBLE ENTRY AND UNLAWFUL DETAINER In forcible entry or unlawful detainer cases, the only damage that can be recovered is the fair rental value or the reasonable compensation for the use and occupation of the leased property. The reason for this is that the only issue raised in ejectment cases is that of rightful possession; hence, the damages which could be recovered are those which the plaintiff could have sustained as a mere possessor, or those caused by the loss of the use and occupation of the property, and not the damages which he may have suffered but which have no direct relation to his loss of material possession. (Dumo vs. Espinas, G.R. No. 141962, January 25, 2006) The judgment rendered in an action for unlawful detainer shall be conclusive with respect to the possession only and shall in no wise bind the title or affect the ownership of the land or building. Such judgment would not bar an action between the same parties respecting title to the land or building. Section 18, Rule 70 of the Rules of Court provides that when the defendant raises the defense of ownership in his pleadings and the question of possession cannot be resolved without deciding the issue of ownership, the issue of ownership shall be resolved only to determine the issue of possession. (Roberts vs. Papio, G.R. No. 166714, February 9, 2007) Expanded jurisdiction of first level courts in real actions A complaint for reconveyance of a parcel of land which involves title to or interest in real property should allege assessed value of the land. The complaint specified only the market value or estimated value which is P15,000.00. In the absence of an assessed value, or in lieu thereof, the estimated value may be alleged. Sec. 22 of BP 129 as amended by R.A. No. 7691 (where the assessed value of the real property does not exceed P20,000.00 or P50,000.00 in Metro Manila) grants the MTC exclusive jurisdiction over subject case. The nature of an action is determined not by what is stated in the caption of the complaint but its allegations and the reliefs prayed for. Where the ultimate objective of the plaintiff is to obtain title to real property, it should be - 18 filed in the proper court having jurisdiction over the assessed value of the property subject thereof. (Barangay Piapi vs. Talip, 469 SCRA 409 [2005]). What are the kinds of action to recover possession of real property? Under existing law and jurisprudence, there are three kinds of actions available to recover possession of real property: (a) accion interdictal; (b) accion publiciana; and (c) accion reivindicatoria. Accion interdictal comprises two distinct causes of action namely, forcible entry (detentacion) and unlawful detainer (desahuico). In forcible entry, one is deprived of physical possession of real property by means of force, intimidation, strategy, threats, or stealth whereas in unlawful detainer, one illegally withholds possession after the expiration or termination of his right to hold possession under any contract, express or implied The jurisdiction of these two actions, which are summary in nature, lies in the proper municipal trial court or metropolitan trial court. Both actions must be brought within one year from the date of actual entry on the land, in case of forcible entry, and from the date of last demand, in case of unlawful detainer. The issue in said cases is the right to physical possession. Accion publiciana is the plenary action to recover the right of possession which should be brought in the proper regional trial court when dispossession has lasted for more than one year. It is an ordinary civil proceeding to determine the better right of possession of realty independently of title. In other words, if at the time of the filing of the complaint more than one year had elapsed since defendant had turned plaintiff out of possession or defendant’s possession had become illegal, the action will be, not one of the forcible entry or illegal detainer, but an accion publiciana. On the other hand, accion reivindicatoria is an action to recover ownership also brought in the proper regional trial in an ordinary civil proceeding. What determines jurisdiction in unlawful detainer? To vest the court jurisdiction to effect the ejectment of an occupant, it is necessary that the complaint should embody such a statement of facts as brings the party clearly within the class of cases for which the statutes provide a remedy, as these proceedings are summary in nature. The complaint must show enough on its face the court jurisdiction without resort to parol testimony. The jurisdictional facts must appear on the face of the complaint. When the complaint fails to aver facts constitutive of forcible entry or unlawful detainer, as where it does not state how entry was effected or how and when dispossession started, the remedy should either be an accion publiciana or an accion reivindicatoria in the proper regional trial court. (Valdez, Jr. vs. Court of Appeals, G.R No. 132424, May 4, 2006) Accion publiciana is one for the recovery of possession of the right to possess. It is also referred to as an ejectment suit filed after the expiration of one year after the occurrence of the cause of action or from the unlawful withholding of possession of the realty. (Hilario, etc., et. al. vs. Salvador, et. al., G.R. No. 160384, April 29, 2005) Possession by tolerance becomes unlawful from the time of demand to vacate. Petitioner’s cause of action for unlawful detainer springs from respondents’ failure to vacate the questioned premises upon his demand sometime in 1996. - 19 Within one (1) year therefrom, or on November 6, 1996, petitioner filed the instant complaint. It bears stressing that possession by tolerance is lawful, but such possession becomes unlawful when the possessor by tolerance refuses to vacate upon demand made by the owner. (Santos vs. Sps. Ayon, G.R. No. 137013, May 6, 2005) Where the period of the lease has expired and several demands were sent to the lessee to vacate, when should the one year period to file unlawful detainer be reckoned? From the date of the original demand or from the date of the last demand? From the date of the original demand if the subsequent demands are merely in the nature of reminders or reiterations of the original demand. Demand or notice to vacate is not a jurisdictional requirement when the action is based on the expiration of the lease. Any notice given would only negate any inference that the lessor has agreed to extend the period of the lease. The law requires notice to be served only when the action is due to the lessee’s failure to pay or the failure to comply with the conditions of the lease. The one-year period is thus counted from the date of first dispossession. To reiterate, the allegation that the lease was on a month-to-month basis is tantamount to saying that the lease expired every month. Since the lease already expired midyear in 1995, as communicated in petitioners’ letter dated July 1, 1995, it was at that time that respondent’s occupancy became unlawful. (Racaza vs. Gozum, 490 SCRA 313 [June 8, 2006]) SPECIAL PROCEEDINGS RULE 73 The determination of which court exercises jurisdiction over matters of probate depends upon the GROSS VALUE of the estate of the decedent. (Lim vs. CA, 323 SCRA 102 [2000]) Rule 73, Sec. 1 is deemed amended by BP 129, as amended by RA 7691. RULE 74 Respondent, believing rightly or wrongly that she was the sole heir to Portugal’s estate, executed on February 15, 1988 the questioned Affidavit of Adjudication under the second sentence of Rule 74, Section 1 of the Revised Rules of Court. Said rule is an exception to the general rule that when a person dies leaving a property, it should be judicially administered and the competent court should appoint a qualified administrator, in the order established in Sec. 6, Rule 78 in case the deceased left no will, or in case he did, he failed to name an executor therein. (Portugal vs. Portugal-Beltran, G.R. No. 155555, August 16, 2005) Since Josefa Delgado had heirs other than Guillermo Rustia, Guillermo could not have validly adjudicated Josefa’s estate all to himself. Rule 74, Section 1 of the Rules of Court is clear. Adjudication by an heir of the decedent’s entire estate to himself by means of an affidavit is allowed only if he is the sole heir to the estate. (In the Matter of the Intestate Estate of Delgado, G.R. No. 155733, January 27, 2006) - 20 The procedure outlined in Section 1 of Rule 74 is an ex parte proceeding. The rule plainly states, however, that persons who do not participate or had no notice of an extrajudicial settlement will not be bound thereby. The publication of the settlement does not constitute constructive notice to the heirs who had no knowledge or did not take part in it because the same was notice after the fact of execution. (Cua vs. Vargas, G.R. No. 156536, October 31, 2006) RULE 76 According to the Rules, notice is required to be personally given to known heirs, legatees, and devisees of the testator. [Sec. 3, Rule 76, Rules of Court] A perusal of the will shows that respondent was instituted as the sole heir of the decedent. Petitioners, as nephews and nieces of the decedent, are neither compulsory nor testate heirs who are entitled to be notified of the probate proceedings under the Rules. Respondent had no legal obligation to mention petitioners in the petition for probate, or to personally notify them of the same. (Alaban vs. CA, G.R. No. 156021, September 23, 2005) RULE 77 While foreign laws do not prove themselves in our jurisdiction and our courts are not authorized to take judicial notice of them; however, petitioner, as ancillary administrator of Audrey’s estate, was duty-bound to introduce in evidence the pertinent law of the State of Maryland. Petitioner admitted that he failed to introduce in evidence the law of the State of Maryland on Estates and Trusts, and merely relied on the presumption that such law is the same as the Philippine law on wills and succession. Thus, the trial court peremptorily applied Philippine laws and totally disregarded the terms of Audrey’s will. The obvious result was that there was no fair submission of the case before the trial court or a judicious appreciation of the evidence presented. (Ancheta vs. Guersey-Dalaygon, G.R. No. 139868, June 8, 2006) RULE 78 On the matter of appointment of administrator of the estate of the deceased, the surviving spouse is preferred over the next of kin of the decedent. [Under Sec. 6(b), Rule 78, Rules of Court, the administration of the estate of a person who dies intestate shall be granted to the surviving husband or wife, as the case may be, or next of kin, or both, in the discretion of the court, or to such person as such surviving husband or wife, or next of kin, requests to have appointed, if competent and willing to serve.] When the law speaks of “next of kin”, the reference is to those who are entitled, under the statute of distribution, to the decedent’s property; one whose relationship is such that he is entitled to share in the estate as distributed, or, in short, an heir. In resolving, therefore, the issue of whether an applicant for letters of administration is a next of kin or an heir of the decedent, the probate court perforce has to determine and pass upon the issue of filiation. A separate action will only result in a multiplicity of suits. Upon this consideration, the trial court acted within bounds when it looked into and pass upon the claimed relationship of respondent to the late Francisco Angeles. (Angeles vs. Maglaya, G.R. No. 153798, September 2, 2005) Even assuming that Felicisimo was not capacitated to marry respondent in 1974, nevertheless, we find that the latter has the legal personality to file the subject petition for letters of administration, as she may be considered the co- - 21 owner of Felicisimo as regards the properties that were acquired through their joint efforts during their cohabitation. An “interested person” has been defined as one who would be benefited by the estate, such as an heir, or one who has a claim against the estate, such as a creditor. The interest must be material and direct, and not merely indirect or contingent. In the instant case, respondent would qualify as an interested person who has a direct interest in the estate of Felicisimo by virtue of their cohabitation, the existence of which was not denied by petitioners. (San Luis vs. San Luis, G.R. No. 133743, February 6, 2007) RULE 86 Section 5 of Rule 86 of the Rules of Court expressly allows the prosecution of money claims arising from a contract against the estate of a deceased debtor. Evidently, those claims are not actually extinguished. What is extinguished is only the obligee’s action or suit filed before the court, which is not then acting as a probate court. In the present case, whatever monetary liabilities or obligations Santos had under his contracts with respondent were not intransmissible by their nature, by stipulation, or by provision of law. Hence, his death did not result in the extinguishment of those obligations or liabilities, which merely passed on to his estate. Death is not a defense that he or his estate can set up to wipe out the obligations under the performance bond. Consequently, petitioner as surety cannot use his death to escape its monetary obligation under its performance bond. (Stronghold Insurance Company, Inc. vs. Republic-Asahi Glass Corporation, G.R. No. 147561, June, 2006) With regard to respondents’ monetary claim, the same shall be governed by Section 20 (then Section 21), Rule 3 of the Rules of Court which provides: SEC. 20. Action on contractual money claims. – When the action is for recovery of money arising from contract, express or implied, and the defendant dies before entry of final judgment in the court in which the action was pending at the time of such death, it shall not be dismissed but shall instead be allowed to continue until entry of final judgment. A favorable judgment obtained by the plaintiff therein shall be enforced in the manner provided in these Rules for prosecuting claims against the estate of a deceased person. (21a) In relation to this, Section 5, Rule 86 of the Rules of Court states: SEC. 5. Claims which must be filed under the notice. If not filed, barred; exceptions. – All claims for money against the decedent arising from contract, express or implied, whether the same be due, not due, or contingent, ... and judgment for money against the decedent, must be filed within the time limited in the notice; otherwise they are barred forever, except that they may be set forth as counterclaims in any action that the executor or administrator may bring against the claimants… Thus, in accordance with the above Rules, the money claims of respondents must be filed against the estate of petitioner Melencio Gabriel. (Gabriel vs. Bilon, G.R. No. 146989, February 7, 2007) RULE 102 - 22 The writ of habeas corpus applies to all cases of illegal confinement or detention in which individuals are deprived of liberty. It was devised as a speedy and effectual remedy to relieve persons from unlawful restraint; or, more specifically, to obtain immediate relief for those who may have been illegally confined or imprisoned without sufficient cause and thus deliver them from unlawful custody. It is therefore a writ of inquiry intended to test the circumstances under which a person is detained. The writ may not be availed of when the person in custody is under a judicial process or by virtue of a valid judgment. However, as a post-conviction remedy, it may be allowed when, as a consequence of a judicial proceeding, any of the following exceptional circumstances is attendant: (1) there has been a deprivation of a constitutional right resulting in the restraint of a person; (2) the court had no jurisdiction to impose the sentence; or (3) the imposed penalty has been excessive, thus voiding the sentence as to such excess. (Go vs. Dimagiba, G.R. No. 151876, June 21, 2005) From the foregoing, it is evident that Te is not entitled to bail. Respondent judge contends that under Section 14, Rule 102 of the Rules of Court, he has the discretion to allow Te to be released on bail. However, the Court reiterates its pronouncement in its Resolution of February 19, 2001 in G.R. Nos. 14571518 that Section 14, Rule 102 of the Rules of Court applies only to cases where the applicant for the writ of habeas corpus is restrained by virtue of a criminal charge against him and not in an instance, as in the case involved in the present controversy, where the applicant is serving sentence by reason of a final judgment. (Vicente vs. Majaducon, A.M. No. RTJ-02-1698 (Formerly OCA IPI No. 00-1024-RTJ), June 23, 2005) In a habeas corpus petition, the order to present an individual before the court is a preliminary step in the hearing of the petition. The respondent must produce the person and explain the cause of his detention. However, this order is not a ruling on the propriety of the remedy or on the substantive matters covered by the remedy. Thus, the Court’s order to the Court of Appeals to conduct a factual hearing was not an affirmation of the propriety of the remedy of habeas corpus. (In the Matter of the Petition for Habeas Corpus of Alejano vs. Cabuay, G.R. No. 160792, August 25, 2005) Under Section 1, Rule 102 of the Rules of Court, the writ of habeas corpus extends to “all case of illegal confinement or detention by which any person is deprived of his liberty, or by which the rightful custody of any person is withheld from the person entitled thereto.” The remedy of habeas corpus has one objective: to inquire into the cause of detention of a person, and if found illegal, the court orders the release of the detainee. If, however, the detention is proven lawful, then the habeas corpus proceedings terminate. In this case, Kunting’s detention by the PNP-IG was under process issued by the RTC. He was arrested by the PNP by virtue of the alias order of arrest issued by Judge Danilo M. Bucoy, RTC, Branch 2, Isabela City, Basilan. His temporary detention at PNP-IG, Camp Crame, Quezon City, was thus authorized by the trial court. Moreover, Kunting was charged with four counts of Kidnapping for Ransom and Serious Illegal Detention in Criminal Case Nos. 3608-1164, 3537-1129, 3674-1187, and 3611-1165. In accordance with the last sentence of Section 4 above, the writ cannot be issued and Kunting cannot be discharged since he has been charged with a criminal offense. Bernarte v. Court of Appeals holds that “once the person detained is duly charged in court, he may no longer question his detention by a petition for the issuance of a writ of habeas corpus.” (In the - 23 Matter of the Petition for Habeas Corpus of Kunting, G.R. No. 167193, April 19, 2006) Habeas corpus may be resorted to in cases where rightful custody is withheld from a person entitled thereto. Under Article 211 of the Family Code, respondent Loran and petitioner Marie Antonette have joint parental authority over their son and consequently joint custody. Further, although the couple is separated de facto, the issue of custody has yet to be adjudicated by the court. In the absence of a judicial grant of custody to one parent, both parents are still entitled to the custody of their child. In the present case, private respondent’s cause of action is the deprivation of his right to see his child as alleged in his petition. Hence, the remedy of habeas corpus is available to him. In a petition for habeas corpus, the child’s welfare is the supreme consideration. The Child and Youth Welfare Code unequivocally provides that in all questions regarding the care and custody, among others, of the child, his welfare shall be the paramount consideration. (Salientes vs. Abanilla, G.R. No. 162734, August 29, 2006) RULE 108 Substantial corrections or cancellations of entries in civil registry records affecting the status or legitimacy of a person may be effected through the institution of a petition under Rule 108 of the Revised Rules of Court, with the proper Regional Trial Court. Being a proceeding in rem, acquisition of jurisdiction over the person of petitioner is therefore not required in the present case. It is enough that the trial court is vested with jurisdiction over the subject matter. The service of the order at No. 418 Arquiza St., Ermita, Manila and the publication thereof in a newspaper of general circulation in Manila, sufficiently complied with the requirement of due process, the essence of which is an opportunity to be heard. Moreover, the publication of the order is a notice to all indispensable parties, including Armi and petitioner minor, which binds the whole world to the judgment that may be rendered in the petition. (Alba vs. CA, G.R. No. 164041, July 29, 2005) The petition for annulment and cancellation of the birth certificate of Rosilyn, alleging material entries in the certificate as having been falsified, is properly considered as a special proceeding pursuant to Section 3(c), Rule 1 and Rule 108 of the Rules of Court. The Ceruilas did not comply with the requirements of Rule 108. Under Sec. 3, Rule 108 of the Rules of Court, not only the civil registrar but also all persons who have or claim any interest which would be affected by a proceeding concerning the cancellation or correction of an entry in the civil register must be made parties thereto. As enunciated in Republic vs. Benemerito, unless all possible indispensable parties were duly notified of the proceedings, the same shall be considered as falling much too short of the requirements of the rules. Here, it is clear that no party could be more interested in the cancellation of Rosilyn’s birth certificate than Rosilyn herself. Her filiation, legitimacy, and date of birth are at stake. The lack of summons on Rosilyn was not cured by the publication of the order of the trial court setting the case for hearing for three consecutive weeks in a newspaper of general circulation. Summons must still be served, not for the purpose of vesting the courts with jurisdiction, but to comply with the requirements of fair play and due process. (Ceruila vs. Delantar, G.R. No. 140305, December 9, 2005)