[12] Hirshorn Museum, “Yves Klein and the Gelsenkirchen Opera

![[12] Hirshorn Museum, “Yves Klein and the Gelsenkirchen Opera](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008621891_1-331afa277af6669498b9cf80ff3faaba-768x994.png)

Lynn Basa

Art History: Special Topics- 6450-003

Andrea Ray, Instructor

October 13, 2015

T HE M ANY F ACES OF Y VES

Preamble

I’ve recently realized that the development of my paintings within the last couple of years has been unintentionally paralleling the work of Yves Klein (1928-

1962). I had a superficial knowledge about the artist – International Klein Blue painted on naked ladies who rolled around on canvas – but not much else, and certainly never thought of him as an influence. To be perfectly honest, I always got him a little mixed up with Franz Kline, something I’m no longer too young to be embarrassed to admit. In fact, it was in the course of my research to become less ignorant about the artists lumped into the minimalist and post-minimalist categories that led me to discover I was Klein’s accidental doppelganger.

Now I wonder what steps led Klein along the path his work took in his short career, and what could I learn about my own practice by tracing that path? What questions was he working through? Do they diverge or converge with mine? Will finding this out make any difference to how I think and talk about work? And, does the performative aspect of his process hold clues to where I will go next?

Compare and Contrast

Earlier this year I noticed that the black paintings I’d been doing were starting to get me down so I decided to think of a color I’d prefer to spend more time with. I’ve always liked blue so, despite its popular appeal 1 , I decided to make blue paintings and see where they take me. I intentionally used a different blue than IKB

1

(Golden Paints “phthalo blue green shade,” to be specific) because a dirtier blue seems more complicated and mysterious to me, less synthetic. The formula for

Klein’s signature color is secret but close to a pure ultramarine. Of course I was aware of the inevitable comparisons but I remembered what another artist told me years ago, “Just because Monet painted water lilies doesn’t mean that no other artist can ever paint a water lily.”

As always, I approached this new work with as little self-judgment as possible, allowing myself to disregard the clichés associated with the color even if . I went with the flow of the translucent, ethereal qualities of blue which gradually evolved into a series of embryonic, ur-forms in an attempt to represent the natural forces of the sea and sky.

Lynn Basa, Blue #2 , 30” x 22”

Synthetic polymer on paper, 2015

Lynn Basa, Blue #29 , 30” x 22”

Synthetic polymer on paper, 2015

2

Hex color number for IKB, #0033CC 2 Yves Klein, IKB 79, 55”x 47”

Paint on canvas on plywood, 1979 (Tate

Museum)

Lynn Basa, 2015

Photograph by Doug vanderHoof, Lake

Michigan, Chicago

Yves Klein, 1960

Yves Klein | photograph of the performance "Untitled",

Cagnes sur mer, France, 1960 |

© Yves Klein - ADAGP, Paris

2012 | photograph: © Rotraut | Yves Klein Archives courtesy

3

Yves Klein making Untitled Sponge Relief (RE 28) on the beach in Malibu, California, June 1961.

Lynn Basa making Waterbodies on the beach in Chicago, IL, July 2015. (Photo by Doug vanderHoof)

4

Similarities End

As it turns out, the similarities between my work and Klein’s are superficial and circumstantial, as this chart of somewhat strained dichotomies attempts to show:

Klein

Immaterial

Me

Material

Spiritually inspired Reality-based

Hands-off process Hands-on

Trickster

Performative

Transparent

Private

Stated philosophy Not philosophically driven

Despite the inherent problems in trying to draw comparisons between the values and personalities of two people, this exercise has helped me realize that even though I may have stumbled into making work similar to Klein – or any other artist, for that matter – it doesn’t mean there’s anything more to it than coincidence. My research has helped lay to rest the uncanny experience of repeatedly discovering other artists’ work that looks like mine after I’ve made it. This phenomenon is something I’ve discussed with other artists who’ve reported that the same thing happens to them. Apparently this is so common that it could be named “art student syndrome,” like “medical student disease.” 3

Whether I can relate Klein’s career to my own or not, my research has raised questions other than the ones I started with. I’ve discovered that Klein had this effect on an art world that is still trying to figure him out. Was he sincere about his philosophy or was that part of a strategic mystique? Was he an originator of conceptual art or merely a follower who was good at whipping up publicity? Of course, the answer is all of the above. He seemed to have ridden in on the wave of

5

early performance art while anticipating contemporary art and how to play to the media as much as playing with it.

Leap into the Void, 1960. Yves Klein (French, 1928 –1962), photographed by Harry Shunk (German, 1924–

2006) and Janos Kender (Hungarian, 1937

–1983).

4

The Void

It’s hard to get a fix on Klein. His writings, while extensive, are full of doublespeak and obfuscations. From the beginning his artwork has been elusive to the point of impishness. More than one frustrated critic has called him a trickster.

5

Since 1946 when he and his friends divided up the world and he signed the sky, the concept of the void has appeared in all of his actions. That he “manipulated the forces of the void” 6 is the key to his work.

6

Or tried to. A close reading of his Chelsea Hotel Manifesto reveals numerous contradictions and semicircular reasoning like these:

Having rejected nothingness, I discovered the void. The meaning of the immaterial pictorial zones, extracted from the depth of the void which by that time was of a very material order.

7

Absolute art, what mortal men call with a sensation of vertigo the summum of art, materializes instantaneously. It makes its appearance in the tangible world, even as I remain at a geometrically fixed point, in the wake of extraordinary volumetric displacements with a static and vertiginous speed.

8

So much could be said about my adventure in the immaterial and the void that the result would be an overly extended pause while steeped in the present elaboration of a written painting.

9

I get a sense of someone who knows that he is chasing the ineffable yet keeps going despite its quixotic unattainability. His tone and public personna are consistently upbeat and confident – as they had to be to convince his audience that they are experiencing the void. I wonder if the constant effort of sustaining these illusions led to his premature death of a heart attack at 34.

For an artist in pursuit of the immaterial, he produced over 1000 material objects in 15 years, most of them in the 800 sq.ft. Paris apartment he shared with his wife Rotraut. Of these, the majority of them were “monochromes”. While he

Yves and Rotraut Klein portrait, artist's apartment, 14 rue Campagne-

Première,

Paris,1961, photo by Shunk-Kender.

Getty Images.

7

delved into other colors – pink, orange, gold, each one holding symbolic significance

– it was blue of all the material colors that resonated most with his quest for pure experience through the void.

Painting no longer appeared to me to be functionally related to the gaze, since during the blue monochrome period of 1957 I became aware of what I called the pictorial sensibility. This pictorial sensibility exists beyond our being and yet belongs in our sphere. We hold no right of possession over life itself. It is only by the intermediary of our taking possession of sensibility that we are able to purchase life.

Sensibility enables us to pursue life to the level of its base material manifestations, in the exchange and barter that are the universe of space, the immense totality of nature .

10

The “blue revolution” 11 didn’t stop at easel paintings, IKB found its way onto monumental sponge installations, public monuments, and nude “models” conducted by Klein as brushes.

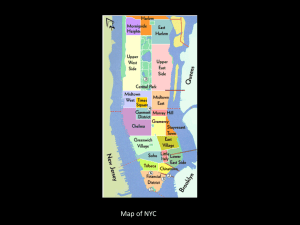

Yves Klein, Gelsenkirchen Opera House, The Ruhr, Germany. Photo Photo © Dietrich Hackenberg 12

8

Did these materials have meaning to him or were they simply the best solution to soaking up and holding paint? I couldn’t find any evidence that they did.

Today, the sponges would be loaded with more than paint and the artist would have to justify using sponges in relation to the destruction of coral reefs or the exploitation of the workers who harvest them. Is a semiological analysis a valid way of looking at this work or would it be finding meaning in materials where none were intended by the artist? Or is the meaning in the fact that the sponges were nontraditional art-making materials?

Klein and a model during the performance "Anthropométries de l'époque bleue," 1960. © 2010 (ARS),

NY/ADAGP, Paris. Photo by ShunkKender, © Roy Lichtenstein Foundation, courtesy Yves Klein Archives.

13

And speaking of loaded, I was surprised and disappointed not to have discovered a feminist critique of Klein’s use of live nude girls in every contemporary account

9

related to his Anthropometries series. To hear him tell it, he began using “models” in his studio because it got lonely in the Void.

I had just removed from my studio all earlier works. The result — an empty studio. All that I could physically do was to remain in my empty studio and the pictorial immaterial states of creation marvelously unfolded. However, little by little, I became mistrustful of myself, but never of the immaterial. From that moment, following the example of all painters, I hired models. But unlike the others, I merely wanted to work in their company rather than have them pose for me. I had been spending too much time alone in the empty studio; I no longer wanted to remain alone with the marvelous blue void which was in the process of opening.

14

The women were consenting adults and, according to Klein, came up with the idea themselves to become his human brushes (presumably because they were tired of sitting around naked watching the genius at work). It would be easy to dismiss this lack of acknowledgment of the power dynamic as being too early in the feminist movement except for the fact that Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex had been out since 1949 – in French, no less. Perhaps because it had been put on the Catholic

Church’s “List of Prohibited Books” 15 that Klein, being a good Catholic, obediently didn’t read.

“Princess Elena” and Yves Klein creating an Anthropometry at his Paris apartment, 1960.

16

10

This 2008 label from MoMA of Klein’s 1960 painting done by dragging the nude body of the model called Princess Helena across a canvas is typical of how

Anthropometries is described today:

Klein employed female models as "living paintbrushes" to make this work and others in his Anthropometry series, named after the study of human body measurements. "In this way," the artist said, "I stayed clean. I no longer dirtied myself with color, not even the tips of my fingers." Klein directed the models, covered in International

Klein Blue

—his patented blue paint—to make imprints of their bodies on large sheets of paper. He staged the making of

Anthropometries as elaborate performances for an audience, complete with blue cocktails and a performance of his Monotone

Symphony

—a single note played for twenty minutes, followed by twenty minutes of silence .

17

Yves Klein, Anthropometry: Princess Helena, 1960

(MoMA)

But, as ever with Klein, things are not always as they seem. In a 2012 videotaped interview, Princess Helena (Elena Palumbo) herself says of the experience, “I was there to help as I considered myself a good friend.” 18

Conclusion

And here is where I throw in the towel. I began this paper motivated to understand if there was anything underlying the superficial similarities between my work and Klein’s. But after learning all about Yves – the judo master, the

11

Rosacrucian, the conductor of ritualistic spectacles -- I’ve come through the other side of the void dazed, muttering, Where was I? What was that? Clutching only the answer to my original question, which is an emphatic No. The path I’m on in my work isn’t even on the same map as Klein’s.

Notes

1 William Jordan, “Why is Blue the World’s Favorite Color?” Accessed Oct. 24, 2015, https://today.yougov.com/news/2015/05/12/why-blue-worlds-favorite-color/ .

2 Color Combos: Hex web color #0033CC, Accessed October 24, 2015, http://www.colorcombos.com/0033CC-hex-color .

3 Medical students' disease (also known as second year syndrome or intern's syndrome) is a condition frequently reported in medical students, who perceive themselves to be experiencing the symptoms of a disease that they are studying.

Accessed Nov. 14, 2015, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medical_students%27_disease

4 From the Met Museum notes: “In October 1960, Klein hired the photographers

Harry Shunk and Jean Kender to make a series of pictures re-creating a jump from a second-floor window that the artist claimed to have executed earlier in the year.

This second leap was made from a rooftop in the Paris suburb of Fontenay-aux-

Roses. On the street below, a group of the artist’s friends from held a tarpaulin to catch him as he fell. Two negatives—one showing Klein leaping, the other the surrounding scene (without the tarp)—were then printed together to create a seamless "documentary" photograph. To complete the illusion that he was capable of flight, Klein distributed a fake broadsheet at Parisian newsstands commemorating the event. It was in this mass-produced form that the artist's seminal gesture was communicated to the public and also notably to the Vienna

Actionists.” Accessed November 15, 2015, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1992.5112

5 Oliver Watts: “de Duve sees Klein‟s constant paradoxes and contradictions as not only the tattle of a “mountebank” but also the illustration of the inconsistency of the

“kettle argument.” In line with Buchloh, de Duve views Klein‟s work as complicit with the ideology of late capital.”

6 Yves Klein, The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, 1961, p1.

7 Klein, The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, 1961, p4.

8 Klein, The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, 1961, p4.

12

9 Klein, The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, 1961, p4.

10 Klein, The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, 1961, p4.

11 Alastair Sooke, “Yves Klein: The Man Who Invented a Color,” BBC Culture, August

24, 2014. Accessed November 16, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20140828-the-man-who-invented-a-colour .

12 Hirshorn Museum, “ Yves Klein and the Gelsenkirchen Opera House,”

Accessed November 16, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_AQw60WiEvU .

13 Caroline Lagnado, “Klein’s Big Leap,” Art21 Magazine, June 20, 2010, Accessed

November 16, 2015: http://blog.art21.org/2010/06/20/kleins-bigleap/#.VkmaeGSrTRY

.

14 Klein, The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, 1961, p4.

15 Wikipedia, The Second Sex. Accessed November 16, 2015: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Second_Sex

16 Sotheby’s catalog, 2012. Accessed November 16, 2015: http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2012/contemporary-artevening-auction-l12020/lot.9.html

.

17 Museum of Modern Art web site. Exhibition label for “Anthropometry: Princess

Helena,” 1960. Accessed November 16, 2015, http://www.moma.org/rails4/collection/works/80530.

18 Christie’s. “Princess Elena: Yves Klein’s Favorite Model,” YouTube video published April 30, 2012. Accessed November 16, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nqoHLpLYISU

_____________________________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Christie’s. Princess Elena: Yves Klein’s Favorite Model. YouTube video published

April 30, 2012. Accessed November 16, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nqoHLpLYISU.

Duve, Thierry de. Sewn in the Sweatshops of Marx: Beuys, Warhol, Klein, Duchamp.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

General Idea. Shut the Fuck Up. 1984, 14 min. Ubu.TV. Accessed Nov. 14, 2015. http://ubu.com/film/general_idea_shut.html

13

Gopnik, Blake. Blake Gopnik reviews 'Yves Klein: With the Void, Full Powers' at the

Hirshhorn. The Washington Post. May 25, 2010. Accessed Oct. 25, 2015. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpdyn/content/article/2010/05/24/AR201005

2402206.html

.

Herman, Daniel. The Free Library. S.v. Elemental logic: Daniel Herman on Yves

Klein's air architecture. Accessed Oct 25 2015. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Elemental+logic%3a+Daniel+Herman+on+Yves+Kl ein%27s+air+architecture.-a0117041639.

Klein, Yves. The Chelsea Hotel Manifesto, 1961. Accessed November 11, 2015. http://www.yveskleinarchives.org/documents/chelsea_us.html

Lacayo, Richard. “Yves Klein: A Master of Blue.” Time, Monday, June 21, 2010.

Accessed October 25, 2015. http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1995856,00.html

.

Rubinyi, Kati and Ewan Branda.“Real Immaterial: Superstudio and Yves Klein.” X-

Tra Contemporary Art Quarterly, Fall 2004, Vol. 7,No. 1. Accessed October 25, 2015. http://x-traonline.org/article/real-immaterial-superstudio-and-yves-klein/ .

Schjeldahl, Peter. “True Blue: An Yves Klein Retrospective.” The New Yorker, June

28, 2010. Accessed October 25, 2015. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2010/06/28/true-blue-3 .

Steinmetz, Julia and Heather Cassils, Clover Leary. “Behind Enemy Lines: Toxic

Titties Infiltrate Vanessa Beecroft.” Signs, Vol. 31, n. 33. December 15, 2005.

Watts, Oliver. “Yves Klein and Hysterical Marks of Authority.” Artsonline, Issue 20,

December 2010. Accessed November 15, 2015. http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/colloquy/download/colloquy_issue_20_december

_2010/watts.pdf

14