Scope - JurisImprudence

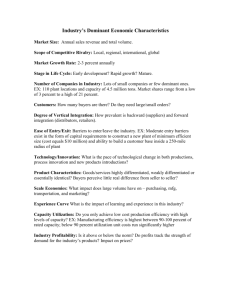

advertisement