StudyAid4112v2 132KB Sep 10 2013 04:46:39 PM

advertisement

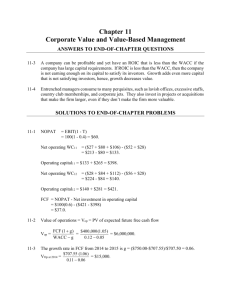

Course 4112 Corporate Valuation Spring 2007 Stockholm School of Economics Robert Johansson 20132 Study aid for Corporate Valuation 4112 Disclaimer: This document is by no means intended to be a summary of either the book by Koller et al., the lecture notes or any of the articles in the compendium. It is rather a simple summary of the points I have felt the need to write down for my own sake to use when studying for the exam. The text definitely does not contain everything you need to know for the exam. Also, no responsibility is taken for any errors contained herein. If such are found, or if you have additional comments to add, you are encouraged to contact me at 20132@student.hhs.se. 1 Reorganizing the Accounting Data 1.1 The Income Statement EBIT +Goodwill amortization/impairment -Taxes on EBITa (Earnings Before Interest and Taxes) EBITA NOPLAT (Net Operating Profil Less Adjusted Taxes) +Depreciation +/- Gains/losses compared to book values Gross Cash Flow - Investments in fixed assets (PPE) - Investments in working capital1 Free Cash Flow (FCF) a) Tax expenses (reported taxes) + TM Interest expense - TM Interest income (on non-operating financial assets)2 - Increase (decreace (-)) in deferred taxes3 Taxes on EBIT4 1.1.1 Financial Cash Flow Conceptually, the Financial Cash Flow is the utilization of Free Cash Flow. Financial Cash Flow consists of all transactions with those providing capital, i.e. shareholders (including minority shareholders in subsidies) and financial creditors. The transactions can be periodic – dividends and interest payments respectively – or changes in the capital stock – new issues/repurchases of share and increase/decrease in debt respectively. The signs I use below imply that the Financial Cash Flow will have the reversed sign compared to Free Cash Flow. One could of course reverse the signs. This would perhaps clarify how Financial Cash Flow is the utilization of FCF. Any increase in operating liabilities is also included here, i.e. added. where TM is the marginal tax rate, i.e. typically 28 percent in Sweden. 3 Sometimes, changes in deferred taxes is reported separately below “Taxes on EBIT” when computing NOPLAT. This is preferred if you are to perform a Value Added Valuation. 4 Beware of using the right signs when computing taxes on EBIT. Your interest expenses should increase your taxes paid (since you are adding back the tax shield) and vice versa for interest income. An increase in deferred taxes means that you have paid less than reported taxes, and the increase should therefore reduce your taxes paid. Whether or not you write expenses with a minus sign or not is then up to you. 1 2 2 + After tax interest income (on non-operating financial assets) - After tax interest expense Increase (+) / decrease (-) in interest bearing debt Increase (-) / decrease (+) in financial assets (e.g. excess cash) Cash from (+) / to (-) minority Cash from (+) / to (-) shareholders5 Financial Cash Flow 1.2 The Balance Sheet To a great extent, Operating Net assets (ONA) and Invested Capital (IC) mean the same thing. However, there is one important difference that has implications for the match between Value Added Valuation and Discounted Free Cash Flow Valuation. When computing IC, deferred taxes are viewed as a sort of equity (or quasi-equity). When computing ONA, deferred taxes are seen as an operating liability and are hence deducted from operating assets when computing ONA. There are some more measurement differences too. VAV and thereby ONA are accounting based (see matrix below under section 2) and typically take the balance sheet for what it is. To calculate IC we make adjustments to arrive at the “true” Invested Capital. The adjustments are things such as capitalizing R&D-expenses and operating leases, adjusting for employee stock options and adding back goodwill amortizations. None of these affect FCF and the adjustments aim at removing the measurement bias in accounting figures to correctly measure performance. This typically implies that it is reasonable to assume that ROIC=WACC in Steady State (SS), whereas RONA is typically greater than WACC even if we assume that there is no business goodwill. However one does, it is important to remain consistent with the market value weights used to compute the WACC. ONA (Operating Net Debt) = Operating Assets – Operating Liabilities ND (Net Debt) = Financial debt6 – Financial Assets E (Equity) = Shareholders’ Equity + Minority Interests ONA (IC) E ND The clean surplus relationship is the most important assumption and it is especially important for the Value Added Valuation and Residual Income Valuation models. The relationship can be stated in different ways. For equity we have Et = Et-1 + Net earnings – Net dividends7 (1) where dividends are net of any new issues of shares. Equivalently for ONA, we have ONAt = ONAt-1 + EBIT (1 – τ) – Free Cash Flow or, stated differently FCF = EBIT (1 – τ) – ONAt (2) This item contains new issues, dividends paid and share repurchases. Typically, no division is made under this statement. This is instead done under the separate headline “Changes in equity”/”Statement of shareholders’ equity”. 6 Typically meaning interest-bearing. This item also includes capitalized operating leases. 7 The implicit assumption made is that dividends are marked to market. 5 3 2 Valuation Techniques Cash Flow Based Accounting Based Value of Operations FCF, APV VAV Equity based The valuation techniques (or models) used in the course are Discounted Free Cash Flow (DCF), Value Added Valuation (VAV), Residual Income Valuation (RIV), Discounted Dividend Model (DDM) and Adjusted Present Value (APV). In addition, multiple- or relative valuation is taught. The techniques can be classified in two dimensions; those that value the whole company (value of operations) versus those that value equity directly and those based directly on accounting data versus those based on cash flow measures. DDM RIV The VAV described in the lectures and the article by Skogsvik is similar to the Economic Profit model described by Koller et al. Jennergren uses the name Economic Value Added (EVA) and makes minor modifications to the model, thereby ensuring its consistency with the VAV model. Jennergren also describes what he calls the Abnormal Earnings Model. This is in essence RIV, only stated slightly differently. Disregarding these name differences, we can define three groups of models that internally give the same result; i) VAV and DCF; ii) RIV and DDM; and iii) APV. The different groups do not, however, always produce exactly the same result. Differences occur primarily because of changing capital structure which in turn affects the different discount rates used. If the leverage ratio stated in market value terms is constant in all years, i.e. including all years in the explicit forecast period, the three groups will give the same result. In SS the capital structure is held constant, and for this period thus, all methods will give the same result. Differences hence result in the explicit forecast period. As noted above, VAV is in essence a restatement of DCF and they (should) therefore produce the same result. To ensure that this happens, one must observe the treatment of deferred taxes. An increase of deferred taxes means that we have reduced the cash taxes paid compared to the reported tax expenses and we will instead report a liability on the balance sheet. In DCF, deferred taxes are viewed as (quasi-)equity and changes in deferred equity are added to NOPLAT when computing FCF. The adding back of the increase (or deduction of the decrease) in deferred taxes ensures that FCF captures the cash flow after taxes actually paid (or “cash taxes”).8 VAV instead see deferred taxes as an operating liability. Hence, any increase in deferred taxes will be included in ONAt = ONAt – ONAt-1 in equation (2) above. Thus, the tax rate τ used in equation (2) should not reflect the change in deferred taxes. It must of course still be corrected for interest income and expenses, thereby being independent of the capital structure. Tax expenses T M Interest expense - T M Interest income EBIT This is of course a lie. Since we also remove the effect of the capital structure from the taxes, “Taxes on EBIT” will not correspond to the taxes the company pays to the IRS. 8 4 3 Discounted Free Cash Flow Well, this one you should know by now. 4 Adjusted Present Value The concept is to first calculate the value of the company as if it were entirely financed by equity and then add the present value of tax shields (and any other cash flows resulting from capital structure, primarily distress costs and issue costs). Start by discounting FCF by the unlevered cost of equity (rEU). This discount rate can be found based on the levered cost of equity (rE) and the cost of debt (rD). If we assume that the risk associated with the tax shield is equivalent to that of the operating assets, we can solve for the unlevered cost of equity as follows. rEU D E rD rE DE DE (3) The formula above corresponds to the levered cost of capital as a function of leverage: rE rEU D rEU rD E (4) Having made the assumption above, one should discount the expected tax shield with the unlevered cost of equity as well.9 Apart from the obvious tax shield, other cash flows related to the capital structure are issue costs and distress costs. This way for computing the unlevered cost of capital is based on an underlying assumption that the capital structure (i.e. leverage ratio in market value terms) is held constant. (This then leads to the conclusion that rtxa = rEU). Cf. section 2 above on consistency between the models. 5 Value Added Valuation RONAt WACC ONAt 1 V (ONAT ) ONAT 1 WACC t 1 WACC T t 1 EBITt (1 ) ONAT RONAT 1 g and RONA ) T V (ONA0 ) ONA0 where V (ONAT WACC g t (5) ONAt 1 Note the definition of τ above and that I let g denote nominal growth. Note also that FCFT 1 ONAT RONAT 1 g The discrepancy between the market and book values stem from accounting conservatism and business goodwill. However, in steady state one typically assumes that there is no more business goodwill and hence that the entire difference is due to accounting conservatism. We can also start by computing RONAT+1 directly. Start with q(ONAT) defined as q (ONAT ) V (ONAT ) 1 ONAT (6) and then have Sometimes, one discounts the tax shield at the cost of debt and calculates the perpetuity present value of the tax shield as (DrDT)/ rD = DT. Note however that since this perpetuity formula does not incorporate growth, we are then assuming a constant dollar value of debt – hardly plausible. 9 5 V (ONAT ) RONAT 1 WACC 1 WACC g WACC q(ONAT ) WACC g ONAT (7) Similarly, the relationship between the market and book value of equity called the permanent measurement bias (PMB) is defined as PMB V ( ET ) 1 ET 6 Residual Income Valuation ROE t rE Et 1 V ( ET ) ET 1 rE t 1 rE T t 1 Net Earnings E ROE T 1 g ) T and ROE T V ( E0 ) E0 where V ( ET rE g t (8) t Et 1 As noted, the formulas are the same as in VAV. The connection between RIV and DDM can be observed by noting the relationship with the familiar Gordon formula below where b is the plowback ratio.10 ET ROE T 1 g EPST 1 (1 b) rE g rE b ROE T 1 In steady state, we have that V ( ET ) ROE T rE 1 rE g ET 7 (9) Discounted Dividend Model As suggested by the name, one needs only to discount the dividends. Remember to use the cost of equity as the discount rate and not the WACC. The horizon value can be calculated using the wellknown Gordon formula directly V ET DIVT 1 DIVT (1 g ) rE g rE g (10) The total value of the equity is then T V E 0 t 1 DIVt 1 rE t DIVT (1 g ) 1 rE g 1 rE T (11) Beware only of the timing of the dividends, i.e. when they are paid out. You must make sure to discount correctly wrt the timing of the cash flows. I copied the formula exactly from one of Jennergren’s articles. He has of course divided both sides by the number of shares outstaning to arrive at Earnings Per Share (EPS). 10 6 8 Multiples Multiples can be grouped along two dimensions; those with denominators from balance sheet items versus those using data from the income statement and those valuing operations versus those valuing equity. Income Statement based Balance Sheet based11 Value of Operations EV/EBIT(DA) EV/ONA(IC) Value of Equity Denominator P/e V(E)/E All multiples are driven by the key value drivers; i) growth, ii) profitability and iii) the cost of capital. However, they will only increase with growth if the return is greater than the required rate of return. All the following formulas apply only in SS, but the conceptual framework is the same wrt the parameters. I have mixed formulas from different models since they highlight different things. EBIT (1 T )1 g NOPLAT 1 g (1 T )1 g ROIC ROIC ROIC EV (12a/b) EV WACC g WACC g EBITA WACC g g DIV Earnings 1 b P 1 b 1 ROE P e r g rE g rE g rE g E V (ONAT ) V ( ET ) ONAT RONAT 1 g V (ONAT ) RONAT 1 g EV WACC g ONAT ONA WACC g ET ROE T 1 g ROE T 1 g Market to Book rE g rE g (13a/b) (14a/b) (15a/b) Apart from these four categories, there are a multitude of non-financial multiples. To derive the Price/Sales ratio, use equation 13a above and note that Earnings = Net margin Sales. 9 Additional Comments Below, I’ve tried to capture some of what could be asked for in the “literature questions”. The main purpose of Jennergren’s forecasting procedure (involving estimating strange parameters etc.) is to get FCF to grow at a constant rate in the horizon period. Both of the multiples in this column can be called Market-to-Book ratio. Sometimes you refer to enterprise value and sometimes to equity value. 11 7 Some main reasons why the clean surplus relationship might not hold include; i) change of financial standards (like the transition to IFRS); ii) a write up (down) of assets directly against equity; and iii) translation differences in international groups. In acquisitions, use the targets WACC to discount the cash flows since this reflects the relevant risk. Also, the target is likely to be most affected, e.g. their staff are more likely to get sacked. Economic Profit = IC [ROIC – WACC] = NOPLAT – IC WACC ROIC tends to regress to a mean but slowly. High profitability is persistent. Growth, however, regress quickly to average levels. High profitability (ROIC) is driven by competitive advantage, typically one of the following; i) price premium, ii) cost competetivness and/or iii) capital efficiency. ROIC (1 ) EBITA Revenues (1 ) Operating margin Capital turns Revenues IC WACC should be based on market value weights in order to reflect the return on an alternative investment (i.e. to sell at market values and invest elsewhere). WACC should be based on target weights because the capital structure at any time could reflect a temporary transition phase (e.g. due to a swing in the stock price) that will not persist. If the changes are large, APV is recommended. 9.1 Taxes Tax claims and liabilities are working capital items. Since these are based on determined taxes, these items are simply debts to or claims on the IRS that will be settled shortly. Deferred tax assets occur when the company is able to postpone the payment of taxes. The strategy is typically to keep these for as long as possible. Deferred tax liabilities occur from e.g. tax loss carry forwards. The company will typically try to realize these as soon as possible. Koller et al. suggests valuing tax loss carry forwards separately as a nonoperating asset. The effective tax rate is the tax rate that gives you the tax expense in the income statement given the pre-tax income. The tax rate used in calculating tax shields is the marginal or statutory tax rate. 9.2 Value Driver Formula Koller et al. uses the value driver formula instead of the Gordon formula. NOPLATT 1 1 g RONIC CV WACC g When ROIC=RONIC then the result is the same as the Gordon. When using Gordon, we should have a forecasting period at least as long as the economic life of PPE to arrive at an even age distribution of PPE in SS. When we have an even age distribution, then NOPLAT will be in SS (i.e. increase with a constant rate) and then ROIC=RONIC. However, it should be noted that the CV formula above does not require that NOPLAT is in SS and one can therefore use a shorter forecast period. (FCF must of course still be in SS.) Thus, if RONICROIC, then we cannot use the VAV continuing value formula. Note also that the numerator is equal to FCF. 8 9.3 Check lists/procedures à la Koller et al. 9.3.1 The forecasting procedure 1) Prepare and analyze historical financials 2) Build the revenue forecast (top-down or bottom-up) 3) Forecast the income statement 4) Forecast the balance sheet: Invested capital and nonoperating assets 5) Forecast the balance sheet: Investor funds (use plug to balance) 6) Calculate ROIC and FCF (make sure they are reasonable wrt industry, market, etc.) 9.3.2 To value a company’s stock 1) Discount FCF 2) Value and add nonoperating assets to arrive at Enterprise Value (EV) 3) Value all nonequity financial claims; i) Debt ii) Debt equivalents, e.g. capitalized operating leases, pension liabilities, certain provisions iii) Employee stock options and convertible debt iv) Minority interest 4) Subtract debt as under (3) and divide by the number of outstanding shares 9.3.3 Analyzing historical performance 1) Reorganize the financial statements 2) Measure and analyze ROIC 3) Break down growth in its components i) Organic ii) Acquisitions iii) Divestures iv) Currency effects v) Accounting changes and other irregularities 4) Asses financial health and capital structure 9.3.4 Analyzing different scenarios When analyzing different scenarios and performing sensitivity analysis, review your assumptions regarding these variables; 1) Broad economic conditions 2) Competitive structure of the industry 3) Internal capabilities of the company 4) Financing capabilities of the company 9.3.5 Best practises when applying multiples 1) Choose comparables with similar prospects for ROIC and growth 2) Use multiples based on forward-looking estimates 3) Use EV multiples based on EBITA to mitigate problems with capital structure and one-time gains and losses. 4) Adjust for nonoperating items (operating leases, excess cash, employee stock options) (5) Use median or harmonic mean rather than arithmetic average) 9 9.3.6 Performance measurement Value is driven by performance and health. Health metrics are forward-looking. 1) Historically, how much value has the company created (i.e. performance)? 2) How well positioned are they to create value in the future (i.e. health)? 3) Is current value in line with the above or if not, why? Performance Growth Health Short-term Medium-term Intrinsic Value ROIC Long-term Organizational Cost of capital Short-term metrics Sales productivity Operating cost productivity Capital productivity Medium-term metrics Commercial health Cost structure health Asset structure health Long-term strategic health Core businesses Growth opportunities Organizational health People, skills, culture (Risk Identify and analyze potential risks) 9.3.7 Performance management 1) Pervasive value creation mind-set The manager should instill a value creation mind-set throughout the business. Employees at all levels should understand the principle of value thinking, know why it matters, and make decisions in the context of the impact on value. 2) Value drivers and value metrics A value driver is an action that affects business performance in the short or long term and thereby creates value. To measure how well the business is performing in relation to these value drivers, companies use a mix of value metrics and value milestones. Some companies 10 develop their value drivers and metrics in a two-step process; i) Understand economic links in the business and identify potential value drivers; ii) Identify highest-priority value drivers. 3) Effective target setting Set targets that are challenging but realistic enough to be “owned” by the managers responsible for meeting them. 4) Fact-based performance review Performance reviews should not be anecdotal, but should be based on measurable facts. 5) Accountability in evaluation and remuneration Create accountability and rewards for individual managers and employees. 9.4 Capital structure Leverage has its costs and benefits: (I hope you took 4103 Corporate Finance.) + - Tax savings Cost of business erosion and bankruptcy (Direct bankruptcy cost & lost opportunities) Reduction of over-investment and perks Cost of conflicts between share- and debtholders (Underinvestment and asset-substitution) The higher a company’s returns, the lower its growth and risk and the more tangible its assets, the more highly leveraged should it be and vice versa. Pecking-order theory focuses on signals sent. You prefer retained earnings over issuing debt over issuing shares. The theory fails to explain long-run effects (i.e. it falsly predict that mature, profitable companies should be less levered) but does explain short-run trade-offs to financing projects quite well. Setting an effective capital structure is based on three analyses: 1) Peer group comparison 2) Credit-rating analysis 3) Cash flow analysis (flexibility versus robustness) Coverage tells you if the company can meet its debt obligations in the short-run. Leverage tells you if it can meet them in the long run. Solvency measures leverage in book-value terms but is seldom relevant. Coverage EBIT(D)A Net Debt or Interest EBITDA When managing a capital structure, one must consider both transaction costs and signalling effects. 9.4.1 Developing long-term capital structure for a company 1) Project financing surplus or deficit 2) Set target credit rating and ratios 3) Develop capital structure for base case scenario 4) Test capital structure under downside scenario 5) Decide on current and future actions 11 9.5 M&A and divestures The framework for analyzing acquisitions is about the price (premium) paid versus the (potential and realized) synergies. There are three reasons why the premium is often higher than the value of synergies (i.e. the acquisition is a loss for the acquirer): 1) Winner’s curse 2) Free-rider problems (with the targets shareholders) 3) Hubris (overestimation of synergies/over optimism) Synergies can be: 1) Cost synergies 2) Revenue synergies 3) Capital synergies (not explicitly mentioned by Koller et al.) But there are always implementation costs. When deciding whether to pay in cash or stock, consider: 1) if you and/or your target are over-/undervalued. 2) how confident you are about realizing the synergies. The more confident you are, the more you lean towards paying in cash. 9.5.1 To become a successful acquirer 1) Earn the right to acquire by having strong core business. 2) Consider only targets for which you can improve future FCF. 3) Excel in estimating overall value creation. 4) Maintain discipline during negotiation. 5) Rigorously plan and execute the integration. 9.5.2 Types of divestures Private transactions 1) Trade sale (sale of part or all of a business) 2) Joint venture Public transactions 3) Initial Public Offering (sale of all shares to new shareholders) 4) Carve-out (safe of part of the shares to new shareholders) 5) Spin-off (giving out shares to parent’s shareholders as dividends) 6) Split-off (offer existing shareholders to exchange parent’s shares for new shares) 7) Tracking-stock (issuing separate class of parent’s shares. No legal separation.) Divestures create value if another party is willing to pay more for a business than the value the parent company expects to extract from that business. 12