October 2006

advertisement

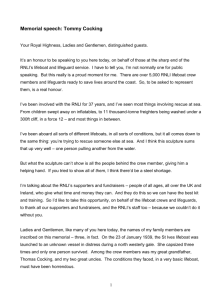

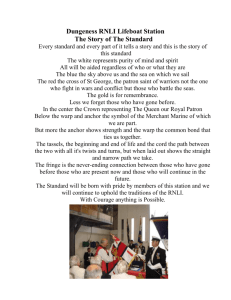

28 Feb 2008 Ref: HQ015 2008 Courageous RNLI lifeboat crews recognised after eight lives saved The Coxswain of the Torbay RNLI lifeboat, Mark Criddle, is to be honoured by the Royal National Lifeboat Institution as the charity awards him the Silver Medal for Gallantry, recognising him for his leadership and outstanding seamanship during the rescue of eight seamen from the stricken merchant vessel Ice Prince on the night of 13 January 2008. Coxswain Criddle’s volunteer crew on that night – Deputy Second Coxswain Roger Good, Second Coxswain John Ashford, Mechanic Mathew Tyler, Second Mechanic Nigel Coulton and Crew Members Darryll Farley and Alex Rowe – have also be recognised for their bravery and will each receive the Thanks of the Institution inscribed on Vellum. The 6,395 gross tonne vessel Ice Prince with 20 crew on board was on passage 34 miles south east of Berry Head, Devon when severe gale force 9 winds and rough seas shifted its cargo of timber causing the vessel to list 25 degrees to port. Brixham Coastguard coordinated the rescue, requesting RNLI lifeboats from Torbay and Salcombe to launch along with the Coastguard rescue helicopter. The Royal Navy frigate HMS Cumberland was at anchor in Torbay and offered to travel to the scene to take up position near the cargo vessel to provide shelter from the weather for the rescuers. By 8.17pm the Ice Prince reported an increase list – now 45 degrees – and had lost all power. The lifeboat and helicopter crews had every reason to think that the vessel could founder, and so RNLI’s Torbay lifeboat increased its speed to 20 knots even though at times this resulted in the lifeboat clearing the water. The helicopter arrived on scene at 9pm and began to winch off nonessential crew from the Ice Prince. Torbay lifeboat was unable to communicate with the helicopter or the stricken vessel, however Coxswain Criddle positioned the lifeboat so that he could assist the rescue efforts by illuminating the scene by searchlight. The pilot used tremendous skill to position and hold the helicopter steady for winching operations due to the list of the cargo vessel. While airlifting the 12 men three hi-lines winch cables broke, each time being replaced, and on two The RNLI is a registered charity that saves lives at sea. It provides, on call, the 24hour service necessary to cover search and rescue requirements to 100 nautical miles out from the coasts of the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland. There are over 230 lifeboat stations. RNLI Lifeguards operate on many of the busiest beaches in the UK. The RNLI further saves lives through sea and beach education. The RNLI depends on voluntary contributions and legacies for its income. Vision To be recognised universally as the most effective, innovative and dependable lifeboat and lifeguard service. Royal National Lifeboat Institution headquarters: West Quay Road, Poole, Dorset, BH15 1HZ Tel 0845 122 6999 Fax 0845 126 1999 A charity registered in England, Scotland and the Republic of Ireland occasions the RNLI lifeboat crew were certain that the helicopter would actually hit the ship. As a tribute to their courage and determination during the rescue, the RNLI will present to Captain Kevin Balls and the crew of the Coastguard rescue helicopter India Juliet the Thanks of the Institution inscribed on Vellum. The RNLI’s Salcombe lifeboat arrived on scene at 9.30pm and also helped to illuminate the vessel as winching continued. The helicopter left the scene at 10pm with 12 rescued crewmen on board. Both Coxswains could see that there were still crewmen on board. At 10.10pm Coxswain Criddle contacted the Master of the Ice Prince, who said he and the remaining crew were preparing to abandon ship. It was at this point that Coxswain Criddle realised his role had changed from a supporting one for the helicopter, to one where he and his crew now needed to evacuate the last eight crewmen on board. Coxswain Criddle quickly briefed his crew, who took up their positions, and then they carried out several trial runs alongside the Ice Prince, as there was serious danger of collision due to its precarious position and the extremely rough sea conditions. The Coxswain of Salcombe RNLI lifeboat was asked to stand by in case any of the eight crew, who would have to be coaxed to cross the steeply sloping deck to leap onto the lifeboat, slipped into the sea. With the noise of the sea and wind limiting communications to hand signals, and with the rolling motion and sideways drift of the vessel combined with the broken water around her stern, there was only a limited area for the lifeboat to get alongside the Ice Prince. So the crew of the Torbay lifeboat set about the first of over 50 approaches to rescue the eight crewmen. Several attempts were needed to rescue each crewman, each time the lifeboat and crew were at risk from the submerged superstructure of the vessel, the severe rolling motion of the vessel and the unstable cargo. Also, if Coxswain Criddle overshot the approach there was a real danger of the vessel’s starboard quarter smashing down on to the lifeboat’s bow where the crew were positioned. This did not deter the RNLI volunteer crew, who were totally focused on rescuing the eight men still on board. With the first three rescued, the fourth was in position when the Torbay lifeboat rolled unpredictably and the two vessels collided. The man ended up under water, at which point the Salcombe RNLI lifeboat began to manoeuvre into a position to rescue him. However, he managed to clamber along the submerged section of the ship and get back to his colleagues; he was then able to get onto the Torbay lifeboat on the next approach. The Torbay crew had been thrown onto the deck of the lifeboat, but quickly got back into position to continue rescuing the remaining Ice Prince crew, all of whom now needed much persuading to attempt the transfer. During one of the attempts, one crewman’s jump was short and he came close to being caught between the two vessels. However the Torbay’s foredeck crew grabbed him and hauled him on board. The remaining crewmen were rescued, but each time the lifeboat crew had to lean forward to catch them, risking being struck by the starboard quarter of the Ice Prince. Rescuing the eight men had taken one and three quarter hours of constant manoeuvring in close proximity to a listing, rolling, powerless, cargo ship at night in atrocious conditions. Salcombe RNLI lifeboat Coxswain Marco Brimacombe along with his crew on board that night – Second Mechanic Richard Whitfield and Crew Members Andrew Arthur, Simon Cater, James Fern and Josh Dornom – will receive collectively the RNLI Chief Executive’s Letter of Thanks for their part in this long and arduous lifesaving service. RNLI Divisional Inspector, Simon Pryce says: ‘Coxswain Criddle showed great leadership and direction during the rescue operation when he and his crew saved the lives of eight men in perilous conditions – conditions that were severe enough to cripple a 6,395 gross tonne ship. The crew were well aware of the dangers they faced, but recognised that the eight crew of the Ice Prince were in a lifethreatening situation. The actions taken by the Coxswain and lifeboat crew were done under the absolute belief that the Ice Prince could capsize and sink at any moment. ‘The crew of the lifeboat showed tremendous bravery, tenacity and strength, acting as a well-trained, efficient team. ‘Coxswain Criddle’s boat handling skills were put to the test during the rescue – even though he pushed the lifeboat to its limits and made over 50 runs alongside the stricken vessel in severe sea conditions, the lifeboat under his command sustained only minimal damage.’ ‘Others involved with the rescue on the night – the Coastguard and helicopter crew, HMS Cumberland and the RNLI’s Salcombe lifeboat all acted in the best traditions of lifesaving at sea – they can all be proud of a job well done.’ Ends Notes to editors 1. Video grabs from actual and reconstruction footage showing the lifeboat and the stricken vessel in position during the rescue are attached to the email. 2. A photo image of Mark Criddle, Coxswain of the Torbay RNLI lifeboat being thanked by the Master of the MV Ice Prince, Arvanitis Charalampos, is also attached to the email. 3. Charts detailing vessel positions are available on request using the contacts below. 4. Mark Criddle will receive his award at the RNLI’s annual presentation of awards at the Barbican on 22 May 2008. Other awards will be presented locally, dates to be confirmed. 5. The RNLI is a registered charity that continues to rely on voluntary contributions, corporate donations and legacies for income and receives no UK Government funding. 6. The RNLI’s annual running costs are over £122M – approximately £335,000 per day. 7. There are over 230 RNLI lifeboat stations across the UK and Ireland, which are operated by 4,800 RNLI lifeboat crew members, of which 95 per cent are volunteers. 8. RNLI Awards: The RNLI has always granted recognition to crew members who have displayed gallantry and/or merit. The four senior awards are, in descending order: The Gold Medal for Gallantry The Silver Medal for Gallantry The Bronze Medal for Gallantry The Thanks of the Institution inscribed on Vellum These awards can only be made by the Trustees of the RNLI Further to this, meritorious service deserving of formal recognition can be recognised by the following, in descending order: A Framed Letter of Thanks signed by the Chairman of the RNLI A Letter of Appreciation signed by the Chief Executive of the RNLI A Letter of Appreciation signed by the Operations Director of the RNLI RNLI media contacts For more information please telephone RNLI Public Relations on 01202 336000 or email pressofffice@rnli.org.uk The RNLI online For more information on the RNLI please visit www.rnli.org.uk or www.rnli.ie. News releases and other media resources are available at www.rnli.org.uk/press. Full rescue scenario Torbay RNLI lifeboat, 13 January 2008 Service to MV Ice Prince – eight lives saved At 7.32pm on Sunday 13 January 2008, Brixham Coastguard, requested the launch of the RNLI’s Torbay all-weather lifeboat to go to the aid of the MV Ice Prince, a 6,395 gross tonne cargo vessel with a crew of 20. The vessel was mid channel on passage to Alexandria however, the adverse weather had caused her cargo of timber to shift, resulting in a 25 degree list to port. At 7.44pm the lifeboat launched with Coxswain Mark Criddle, Deputy Second Coxswain Roger Good, Second Coxswain John Ashford, Mechanic Mathew Tyler, Second Mechanic Nigel Coulton and crew members Darryll Farley and Alex Rowe on board. High water at Plymouth was 9.04pm. Weather conditions were poor with the wind southerly force 8 to 9 and rough seas. Communications were established with Brixham Coastguard, who reported the vessel’s position as 34Nm to the SE of Berry Head. The vessel was reported as listing heavily to port due to her cargo of timber shifting and that her main engines were disabled. With no main propulsion available, the Ice Prince was being set to the SSE at a rate of 4kts. At the same time, the Royal Navy vessel HMS Cumberland, a Type 22 frigate of 5300 gross tonnes and 148 metres in length, informed Brixham Coastguard that they were at anchor in Torbay and would make ready for sea in case they could be of assistance. Coxswain Criddle gave an ETA at the Ice Prince of two hours based on the prevailing sea state. For the previous six hours the tide had been opposing the gale force winds and the waves had built to an estimated four metres with occasional breaking crests. As the lifeboat cleared Start Point, she met the full force of the weather and Coxswain Criddle instructed his crew to wear their full seat harnesses. Salcombe Lifeboat had also been launched on service and was making a best speed of 15kts towards the vessel. In command was Coxswain Brimacombe, also on board were Second Mechanic Richard Whitfield and Crew Members Andrew Arthur, Simon Cater, James Fern and Josh Dornom. At 8pm HMS Cumberland informed Brixham Coastguard that they were making preparations to go to the assistance of the Ice Prince and were in the course of weighing anchor. At 8.17pm Brixham Coastguard asked the Torbay Lifeboat for a revised ETA and reported that the Ice Prince was now listing some 45 degrees to port. She had lost all power from her engines and generators and was operating on emergency batteries. The Coastguard had tasked the Rescue Helicopter India Juliet to assist with the service, as it seemed likely that it would be necessary to evacuate the crew from the stricken vessel. The Torbay lifeboat had been trying, unsuccessfully, to contact the Ice Prince on VHF radio and all communications with the vessel had to be relayed through Brixham Coastguard. Concerned that the ship was in imminent danger of capsizing, Coxswain Criddle ordered the lifeboat’s speed to increase to 20kts giving an ETA of 45 minutes. Even with the lifeboat fully trimmed to keep the bow down the lifeboat left the water on a number of occasions due the very rough sea conditions. As it was dark and the lifeboat was making a lot of spray, so a close radar watch was maintained. The crew could see little out of the wheelhouse windows and it was not safe for crew to be on the deck. At 8.21pm, HMS Cumberland updated her ETA to 10pm and reported she would try to form a lee to assist the rescue effort. At this time the position of the Ice Prince was 37Nm SSE of Berry Head. At 9pm Rescue Helicopter India Juliet was on scene and preparations were being made to winch non-essential crew from the vessel. On board the Torbay lifeboat, Mechanic Tyler tried to establish communications with the helicopter to ascertain how the lifeboat could best assist, but no reply was received. At 9.13pm the rescue helicopter began winching having lowered her winch man to the lower port bridge wing via hi-line. Arriving on scene four minutes later, Coxswain Criddle found the Ice Prince listing heavily to port with the wind on her starboard beam. Weather conditions on scene were poor, with gale force winds from the south west and rough seas and swell in excess of four metres, which was causing the casualty to roll heavily. The vessel’s crew were grouped on the higher, starboard bridge wing, however due to the angle of list, the helicopter pilot, Captain Kevin Balls, had to stay on the ship’s port side. Had he positioned his aircraft above the higher, starboard bridge wing he would not have been able to reference against the ship to allow for her roll. For this reason Winchman Gary Mitchell was lowered to the port bridge wing and had to call the crew down to the port side to be lifted. The four-metre swell was causing the ship to roll heavily and the pilot needed tremendous skill to adjust for it in order to maintain the helicopter’s position. When the vessel rolled the ship’s aerials were coming perilously close to the helicopter’s rotor blades and on two occasions the lifeboat crew thought that the helicopter must surely hit the ship. There was a lot of turbulence coming off the ship’s starboard side and the pilot had to apply full power in order to pull away from the ship. The helicopter broke three of her five hi-lines and on each occasion had to repeat the operation and lower a new hi-line to the winchman. During winching operations, Coxswain Criddle positioned his lifeboat head to weather off the vessel’s port quarter and on the helicopter’s starboard side. Crew Member Darryll Farley was on the flying bridge of the lifeboat with Coxswain Criddle and was directing the searchlight to illuminate the ship. Mechanic Tyler was still unable to raise the helicopter on the VHF. Salcombe RNLI lifeboat arrived on scene at 9.30pm and Coxswain Brimacombe positioned his lifeboat off Torbay lifeboat’s port quarter where she could best help to illuminate the scene with her searchlights. HMS Cumberland arrived on scene at 9.55pm and took up a position on the vessel’s windward side to provide a lee for the rescue effort. At 10pm the rescue helicopter had lifted off twelve crewmen from the Ice Prince and informed Brixham Coastguard that they were returning to Portland; still no contact had been made by either lifeboat with the helicopter. The crew of both lifeboats were unsure of the situation on board the casualty vessel and it was only because they were still illuminating the bridge of the Ice Prince that the lifeboat crew realised that there were still crew on board. Up until this moment, Coxswain Criddle had thought that the helicopter would evacuate all the crew and that the lifeboat’s role would be one of support. With the helicopter leaving for Portland, he realised that the situation had altered dramatically and that he and his crew might be called upon to evacuate the remaining crew. At 10.10pm, Coxswain Criddle spoke to the Master of MV Ice Prince on the VHF radio to ask his intentions and he stated that he was preparing to order his crew to abandon ship and asked if the lifeboat was prepared to take the crew off. Coxswain Criddle agreed, but requested that all of the Ice Prince’s crew should wear immersion suits and lifejackets with lights on. The transfers would be done one person at a time off the vessel’s stern; the Master agreed. Coxswain Criddle briefed his crew of the new situation, instructing them to use their safety harnesses and helmets at all times and to make their way to the foredeck. Crew Member Farley was to stay on the bridge with Coxswain Criddle to operate the searchlight. All the lifeboat’s fenders were rigged on the port shoulder, along with the port ‘A’ frame fitted with two rescue strops. Additionally, a third rescue strop attached to a long floating line was prepared, which was to be used should one of the vessel’s crewmen fall into the water. The wind was still gale to severe gale force 8 to 9 and the four to five metre swell with occasional breaking waves was presenting a significant challenge to the Coxswain and crew of the lifeboat. The noise of the seas and the wind made communications among the foredeck crew very difficult, but having been briefed as to the task in hand they settled to it immediately. When all of his crew were ready and secure on the foredeck, Coxswain Criddle made three or four practice runs at the casualty’s stern to see how the vessels would interact. There were a number of aspects of the approach to the ship, which were causing him concern: the Ice Prince was beam on to the wind and drifting at 3 knots; her list meant that her port side was under water and the port gunwale was an invisible but obvious danger; she had a large Admiralty Pattern anchor housed on her stern reducing the available area to come alongside; her heavy rolling presented a very real danger of the vessel’s starboard quarter coming down onto the lifeboats bow, were the lifeboat to overshoot her approach; and there was a concern about the ships cargo – but very little flotsam was seen and it appeared that all the ship’s warps were securely stowed. The ship had her emergency lights on which were illuminating the after deck, but the only real illumination came from the lifeboat’s searchlight. Crew Member Farley was doing an excellent job, as it was difficult to stand on the upper steering position let alone coordinate the searchlight with the stricken vessel’s movement. At one point he fell forward cutting his forehead on the lights housing. Second Coxswain Good positioned himself outboard the inner pulpit and used his harness to secure himself so he had both hands free if necessary to assist the crewmen on board. He signalled to Coxswain Criddle that the foredeck crew were ready and indicated to the vessel’s crew to prepare for transfer. Crew Member Ashford, secured by his safety harness, was just forward of the pulpit with Mechanic Tyler, and Crew Member Rowe were just aft of it. Second Mechanic Coulton was positioned at the forward end of the port guardrail. His job was to take the rescued crewmen back to the wheelhouse and for this reason he was not using his safety harness. The eight remaining crew on the Ice Prince were all positioned at the rear of the accommodation block on the starboard side. To make the transfer to the lifeboat they would have to cross the steeply sloping deck to the vessel’s port side anchor winch, which was best achieved by crossing to the starboard anchor winch, then to the ensign staff and finally to the port anchor winch. This placed them in a good position to make the transfer to the lifeboat. With the ship rolling heavily traversing to the anchor winch was difficult and dangerous for the remaining crewmen and the position of the stern anchor afforded limited space for the lifeboat to come alongside. The rolling of the vessel was making the starboard quarter act like a guillotine and Coxswain Criddle was concerned that if he overshot the crew on the lifeboat’s foredeck could be crushed. The casualty vessel was being blown to leeward at 3.5kts adding to the difficulty of an accurate approach. The eight crewmen had not brought a handheld radio with them so all communications from this point had to be done by hand signals. With the first of the remaining crewmen ready at the stern anchor winch, Coxswain Criddle made his approach to put the port shoulder against the stern of the Ice Prince. The manoeuvre went to plan and the first crewman was able to step across into the arms of the waiting lifeboat crew. Once on board he was lead aft by Second Mechanic Coulton and taken to the wheelhouse and then down below while Coxswain Criddle backed away and set up for another run in. Second Mechanic Coulton made his way back to the foredeck as quickly as possible. The motion of the lifeboat was making normally simple tasks difficult and required an enormous amount of additional effort and skill to undertake them. When the second crewman was in position, the manoeuvre was repeated and he came on board without difficulty and was escorted to the wheelhouse. This routine was repeated with the third man. Each transfer required a number of approaches to achieve the transfers because the sideways motion of the ship, coupled with her rolling and the broken water around her stern meant that there was no safe way of holding the lifeboat in position. These manoeuvres demanded tremendous skill and concentration from Coxswain Criddle in order to guide the lifeboat close enough to the stricken vessel without hitting her, while at the same time being close enough to allow a transfer. Coxswain Criddle had realised that the area around his own port side, adjacent to the Ice Prince’s port quarter presented an areas of significant risk were one of the crewmen to slip down the deck into the sea. In order to minimise the risk, Coxswain Criddle asked the Salcombe lifeboat to standby off the ship’s port quarter should one of the men be unlucky enough to find themselves in such a situation. The submerged port rail, which was not visible, but obviously rising and falling below the water also presented an additional danger to anybody falling into the water. While coming alongside to pick up the fourth crewman, the Torbay lifeboat rolled unpredictably and the two vessels collided heavily. It is thought that the crewmen either jumped backwards or let go of the rail, causing him to slip down the deck of the Ice Prince. Coxswain Criddle feared that he had fallen between the two vessels and quickly came astern. At the same time he could hear the Salcombe lifeboat manoeuvring and realised that they had seen the crewman in the water. He had slid down the deck just as Coxswain Criddle had foreseen. Luckily, due to the surging motion of the water in this area, the crewman was able to haul himself back up the deck and back to the anchor winch. On the next approach he stepped aboard calmly and was taken back to the wheelhouse where he was found to be unhurt. The foredeck crew had been thrown to the deck when the two vessels collided, which had caused the fendering on the lifeboat’s port bow to be torn off. Shaken but without thought to his own safety, each man again took up his position. Coxswain Criddle again set the lifeboat up and made another approach but on this occasion the four remaining crew could not be persuaded to come down the deck and make the transfer. The lifeboat made numerous approaches but despite his crew using all their persuasive powers, the remaining crewmen were not willing to jump across onto the lifeboat. Coxswain Criddle tried power to push the bow of the lifeboat against the ship’s stern to make the transfer easier but the motion of the sea was too great and it soon became obvious that this was not a viable option. This resulted in more damage to the fendering on the port bow and the bow roller. Repeated manoeuvres were executed to bring the lifeboat alongside and eventually the crewmen, after much coaxing, were confident enough to come down to the anchor winch. During one of these manoeuvres one of the men half jumped/half fell towards the lifeboat, coming perilously close to being caught between the two vessels. It took the combined efforts of all the foredeck crew to grab hold of him and haul him on board. The lifeboat was placed alongside several more times before the next man could be coaxed across. On each occasion the foredeck crew had to step forward to help and in so doing, faced the danger of being struck by the starboard quarter of the ship. When the sixth crewman did attempt the transfer, he too had to be manhandled on board by the foredeck crew to prevent him from falling into the sea. The final two followed a similar pattern, needing numerous approaches to build their confidence in order that the foredeck crew could physically haul them on board the lifeboat. This had taken one and three quarter hours in atrocious conditions and with over fifty alongside manoeuvres. Throughout, the Salcombe lifeboat stood by using her searchlights to help illuminate the scene. With all eight crewmen safely on board in the wheelhouse, the doctor, Crew Member Alex Rowe assessed them. Two men were cause for concern, but the remaining six, apart from being shocked at what had just happened, appeared well and free from injury. The six unhurt men were taken below and strapped into the seats, the other two were seated on the wheelhouse bench seat and monitored by the doctor. A full internal and external check of the bow area of the was carried out as best as possible by the lifeboat crew to check for any damage that may have occurred when the two vessels collided. With no significant hull damage apart from a broken bow roller and the damaged fendering detected, the decks were secured ready for the return passage to Brixham. Brixham Coastguard was informed that the remaining eight crewmen were on board the RNLI’s Torbay lifeboat and that both lifeboats were returning to station. Torbay lifeboat gave an ETA of 1.20am and an ambulance was requested to attend the two injured crewmen. Although the conditions had not abated, the lifeboat managed to make passage to Brixham at 20kts. At 1.15am the Torbay lifeboat entered Brixham harbour and was moored up on her berth. Two of those saved were taken to the waiting ambulance and the other six were taken to the RNLI boathouse. At 2.15am Torbay lifeboat was re-fuelled and ready for service. Salcombe lifeboat reached Salcombe an hour before low water and was able to cross the bar at 2.30am. She was refuelled and declared ready for service at 3.35am.