Tools, Hands and the Expansion of Intellect

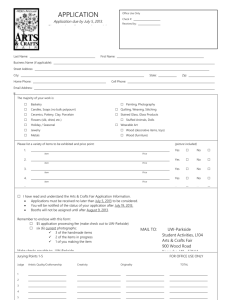

advertisement

Tools, Hands and the Expansion of Intellect Doug Stowe - BA School Woodworking Program Director The Clear Spring School, Wisdom of the Hands PO Box 511 Eureka Springs, Arkansas USA 72632 http://wisdomofhands.blogspot.com emaildouglasstowe@gmail.com Summary Abraham Maslow (American psychologist 1908-1970): “It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”(1) Tools not only provide the power to shape materials, but frame the dimensions of human intellect. There is magic in the manipulation of real tools and real materials. They create interest in the learner by engaging the hands in the exploration of physical reality and the expression of intellect. We place our children at risk of boredom and diminished capacity by abandoning of the commonplace and tools that formed the foundation of human creativity. Research on gesture, the new field of embodied cognition, and new developments in the study of depression reveal the significance of the varied and rhythmic use of the hands in the development of human intellect. We are made stupid when our hands are stilled. Most American schools and homes are involved in a risky experiment in which the common tools of artists and craftsmen are abandoned. The Clear Spring School, a small independent school in Northwest Arkansas is different. We are on the cutting edge in the making and use of tools. Our children make their own, from hand-carved ink pens based on the 1885 Nääs Sloyd model series to the looms our children use in weaving and textiles. Making tools provides a means to put the hand into action in the classroom When the child makes the tools used in his or her hands-on exploration there is a depth of interest and understanding that cannot be approached otherwise. Tools, hands and the expansion of intellect "Let the youth once learn to take a straight shaving off a plank, or draw a fine curve without faltering, or lay a brick level in its mortar, and he has learned a multitude of other matters which no lips of man could ever teach him" --John Ruskin, "Time and Tide", 1883. The United States, unlike the Scandinavian countries does not have a national curriculum in craft education. While many schools in the US have arts education, often taught by a resource teacher and with little integration with core classroom learning, craft education is extremely rare in schools. For that reason, those of us involved in crafts education are challenged to find a clear rationale for its inclusion in schools. Crafts education must compete for funding against many other more widely recognized educational needs, so part of my mission has been to demonstrate its value within a system that has been skeptical. On the more positive side, not having a standardized national crafts curriculum offers craft teachers the opportunity to be exercise personal creativity. To develop a program like my own would not have been possible in schools with greater responsibility to national standards. 1 When I was in high school and college I worked summers and holidays in my father’s hardware store and would slip away for an hour or so each afternoon to restore an old car under the guidance of a master craftsman. He said one day, “Doug, I don’t know why you study to be a lawyer, when your brains are so clearly in your hands.” His comment was prophetic. It led me to reexamine my academic path, alerted me to the pleasure I received in learning and working through my hands, and ultimately caused me to question the artificial and unproductive separation between hands-on learning and academic pursuits. I became a professional craftsman, and then author of woodworking books and articles. Prior to the 1990’s, wood shops were common in middle schools and high schools but since then wood shops have been discontinued to allow greater emphasis to be placed on academic studies. At this point, schools with wood shops have become rare. As a craftsman, author and parent, I had found myself in conversations on the internet in which I learned that wood shops were no longer considered relevant in our “information age”, and that we would all earn our livings by moving electrons from one server to another. Instead of making things we would buy everything we needed from China or some other developing nation. According to widely published statistics, over 30 percent of American high school students fail to graduate. An additional, but unmeasured number of our best and brightest students are bored with their high school educations. Add the numbers of disinterested, and deliberately disruptive students who manage to squeak through at graduation, and you might begin to think we could be doing a better job at educating our children and preparing them for their futures. In my own wood shop, as a professional craftsman I never felt that what I was doing was obsolete. Woodworking enabled me to use a variety of skills, integrating the arts, science, history, mathematics and business. It occurred to me that woodworking in school could become central to the learning experience, making all the other conventional studies more relevant and meaningful to children’s lives. If learning were more relevant, more meaningful and more fun, school would more readily engage our children’s attention and more surely lead to their success. Thanks to my early craftsman mentor I had noticed something about my own hands that I believed to be a valuable tool in education. When the hands are engaged, the heart follows. In the fall of 2001, we launched the Wisdom of the Hands program at Clear Spring School to demonstrate the value of woodcrafts as a part of school curriculum. We named the program Wisdom of the Hands in the belief that bringing the hands into direct action on behalf of learning would enhance learning in all areas of conventional school curriculum and for all students, even those planning to pursue college educations. We started at the high school level and over the next two years, expanded the program throughout grade levels 1 through 12. During that time I began my own research on the role of the hands in learning and I discovered that many of my own ideas were widely shared by educational theorists since the mid 1700’s and are very much a part of modern scientific research today. 2 Tools One of my favorite quotes is from Abraham Maslow (American psychologist 19081970): “It is tempting, if the only tool you have is a hammer, to treat everything as if it were a nail.”i This tells how much our tools are a part of us, how they influence our thoughts and capacities and perceptions of self. The primary method we use in the Wisdom of the Hands program to interject the hands throughout the school curriculum is the making of tools, for it is through the use of tools that the hands take their most active role in the expression of intellect. Thomas Carlyle said, “Man is a tool-using animal. He can use tools, can devise tools; with these the granite mountains melt into dust before him; he kneads iron as if it were soft paste; seas are his smooth highway, winds and fire his unwearying steeds. Nowhere do you find him without tools; without tools he is nothing, with tools he is all!”ii Throughout human history we have used tools to shape our natural environment, and in turn, our use of those tools has given shape to human intellect and perception Charles H. Ham wrote in 1886, “—the axe, the saw, the plane, the hammer, the square, the chisel, and the file. These are the universal tools of the arts, and the modern machineshop is an aggregation of these rendered automatic and driven by steam.”iii As shown by these drawings <drillis1.jpg and drillis2.jpg> from R.J Drillis Folk Norms and Biomechanics, the hands have been the fundamental means through which the world has been shaped, measured, studied and understood. ivAll the actions of machine tools are derived from the motions of the human hand. In addition, while the metric system is based on relative abstraction, earlier concrete systems, including our system of inches and feet, were based on observation of the human hand and other parts of the human body. The Hands As schools have attempted to become more efficient in the process of education, children have been confined to desks with hands stilled, essentially blocking their traditional engagement in the process of learning. According to Dr. Frank Wilson, author of The Hand, How its use shapes the brain, language and human culture,v “No one knows precisely when our ancestors started handling textiles and manufacturing thread, but our ability to do this, along with many other tasks, was made possible because of two critical and parallel changes in upper limb and brain structure. Biomechanical changes in the hand permitted a greatly enlarged range of grips and movements of the hand and fingers; the brain provided new control mechanisms for more complex and refined hand movements. These changes took place over millions of years, and because of the mutual interdependence of hand and brain it is appropriate to say that the human hand and brain co-evolved as a behavioral system. 3 “The entire open-ended repertoire of human manipulative skill rests upon a history of countless interactions between individuals and their environments, natural materials and objects. The hand brain system that came into being over the course of millions of years is responsible for the distinctive life and culture of human society. This same hand-brain partnership exists genetically as a developmental instruction program for every living human. Each of us, beginning at birth, is predisposed to engage our world and to develop our intelligence primarily through the agency of our hands."vi Current research in the new field of embodied cognition recognizes that the whole body takes part in the processing of information and human intelligence. The idea that human knowledge is “brain based” or “language based” no longer provides an accurate view of who we are or how we learn. One of the areas of research involves the use of gesture. Work led by Susan Goldin-Meadowvii, a psychology professor at the University of Chicago, has found that children given arithmetic problems that normally would be too difficult for them are more likely to get the right answer if they're told to gesture while thinking. In fact, students who can use gesture in the solution of algebraic formulas have been shown to be 4 times more likely to get the right answer. Studies by Helga Noice, a psychologist at Elmhurst College, and her husband Tony Noice, an actor and director, found that actors have an easier time remembering lines their characters utter while gesturing, or simply moving. viii There is something extremely powerful about the engagement of the hands. Woodworkers have noted the therapeutic effect of woodworking, calling their time spent in the woodshop, “sawdust therapy.” By and large we feel better when we take the opportunity to immerse ourselves in the process of creating something from wood. In our nation we have an epidemic of depression and other mental and emotional disorders and use of anti-depressant medications have become common for controlling mood and behavior. I came to my own conclusion that much of the problem has been that we have been out of touch with our own hands, and while being out of touch has disastrous consequences in adult lives, it also has profound detrimental effects on the education of our children. The significance of the hand’s role in learning and the feelings that woodworker’s have about the therapeutic aspects of their time in the woodshop are illustrated by research conducted by Dr. Kelly Lambert at the University of North Carolina. She describes a system of “effort driven rewards” resulting from the creative use of the hands, stimulating an exchange of neuro-hormones in the brain that offsets symptoms of depression and raises overall emotional and intellectual engagement in learning.ix The idea that the engagement of the hands in learning and making things might come as a surprise to our nation’s pharmaceutical suppliers, but is no great surprise to those who work with wood. Lambert’s research illustrates how the lack of hands-on engagement leads to emotional disengagement, leading to diminished display of intellectual capacity. This may explain why researcher, Susan Goldin-Meadow suggests, “If you are having trouble thinking clearly, shake your hands.” 4 So the great educational question we must answer in the first part of the 21st century is very much the same question asked by educational theorists at the beginning of the 20th. “How do we bring the hands to bear on the education of our children?” The Demonstration at Clear Spring School The Wisdom of the Hands program is different from conventional school art classes and is different from conventional woodworking programs as well. Each project is planned in cooperation with core classroom teachers to integrate with current studies. By making our own tools at Clear Spring School, we establish a relationship between the materials drawn from our environment and the student’s growth in confidence by capitalizing on the child’s natural inclinations toward creative activity. We make tools that fit a variety of different categories, each intended to enhance the school’s basic curriculum. Some of the tools enable children to do work, while others are used to expand the children’s understanding of concepts. Some are used for investigation and demonstration of scientific principles, some are used for organizing and collecting data and still others provide additional interest in classroom activities. •Working tools are those that provide the children opportunity to do other projects, often involving crafts. Examples are looms for weaving, knives for carving, pens for learning cursive, and pencil sharpeners, among others. •Conceptual study tools include geometric solids for the study of geometry, math manipulatives, models of the solar system, puzzle maps for study of geography and plate tectonics, abacuses for doing math problems and developing numeracy. •Investigatory tools include windmills for studying meteorology, bug boxes and nets for catching insects, and projectile launchers for the study of trigonometry and physics. •Organizational tools include divided trays for the collection of rocks and minerals, display boxes for collections of insects and numbered stakes for marking plant species on the school nature trails. In addition, the children of all ages have a love of making toys and we use toys as tools to expand interest in specific areas of study. As examples, the children have made trains and various animals inspired by their reading. We have made dinosaurs inspired by their study of dinosaurs, as well as boats for the study of the sea, and cars and trucks for the study of economics and transportation. Much of the success of the program is rooted in the close relationship between classroom teachers and the wood shop. Toy making increases the child’s enthusiasm for learning at all ages. Each project tests new ideas and ends with play. Each child at Clear Spring School has a collection of treasured objects that remind of lessons learned, skills developed. The Key to our success: The fact that the classroom teachers are part of the planning process, often suggesting possible projects, leads them to become active wood shop participants, working alongside the students, demonstrating their own engagement in the learning process. Rather than the 5 wood shop being an isolated school activity, it is successfully integrated at all grade levels. By being deeply immersed in exploring the fundamentals of physical reality, and making his or her own tools for discovery, truly no child is left behind, no child is bored, and every child is empowered to engage in creative response to society and environment. The variety of tools that can be made in the school wood shop is without limit. So what is the difference between making an object and making a tool? Tools are intended to have use and impact beyond the time spent in the wood shop. As an example, the simple tray made for the collection of rocks and minerals is not complete until the contents have been collected, organized and labeled. A loom is not complete until it holds a completed textile. A toy is not complete until it has been played with and enjoyed and learned from. Tools have particular effectiveness in bringing the hands to work in the classroom far beyond note taking and keyboarding. The hands’ profound impact on learning has been widely ignored in American education, but may also offer the pathway to educational reform and renewal. Clear Spring School was founded in 1974 in the small town of Eureka Springs Arkansas to serve as a laboratory to explore new principles in progressive education. It serves 80 students from pre-school through high school. It is accredited though ISACS, Independent Schools of the Central States and through NAIS, National Association of Independent Schools.x i Maslow, Abraham, Psychology of Science: a Reconnaissance, (Gateway, 1966) p.-12 Carlyle,Thomas Sartor Resartus, (Ginn 1900) p.-35-36. iii Hamm, Charles H. Mind and Hand, Harper and Brothers, (1886) iv Drills, R. J. Folk Norms and Bimechanics, Human Factors: the journal of the Human Factors Society (Pergamon Press 1963) pages: 427-441 v Wilson, Frank, The Hand, How its use shapes the brain, language and human culture, (Vintage 1998) vi Wilson, Frank. personal email, (January 16, 2005) vii Goldin-Meadow, Susan, Hearing Gesture: How Our Hands Help Us Think, (Belknap Press 2005) viii Bennett, Drake Don’t Just Stand There, Think, Boston Globe (January 13. 2008) http://www.boston.com/bostonglobe/ideas/articles/2008/01/13/dont_just_stand_there_think/ ii ix Lambert, Kelly, PhD. “Depressingly Easy” Scientific American August/September 2008 6