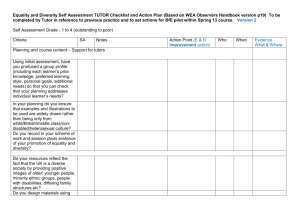

thumbadoo

advertisement