The Role of Ombudsman in Improving Public Service Delivery in

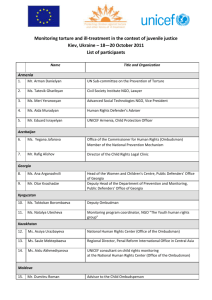

advertisement