Information Literacy and E-learning – Project Report

English Subject Centre Mini Projects

‘HOW DO I REFERENCE AN ARTICLE AGAIN?’

INFORMATION LITERACY AND E-LEARNING

Author: Stacy Gillis

Newcastle University

1

The English Subject Centre

Royal Holloway, University of London

Egham, Surrey TW20 0EX

Tel 01784 443221 Fax 01784 470684

Email esc@rhul.ac.uk www.english.heacademy.ac.uk

English Subject Centre Departmental Projects

This report and the work it presents were funded by the English Subject

Centre under a scheme which funds projects run by departments in Higher

Education institutions (HEIs) in the UK. Some projects are run in collaboration between departments in different HEIs. Projects run under the scheme are concerned with developments in the teaching and learning of English

Language, Literature and Creative Writing. They may involve the production of teaching materials, the piloting and evaluation of new methods or materials or the production of research into teaching and learning. Project outcomes are expected to be of benefit to the subject community as well as having a positive influence on teaching and learning in the host department(s). For this reason, project results are disseminated widely in print, electronic form and via events, or a combination of these.

Details of ongoing projects can be found on the English Subject Centre website at www.english.heacademy.ac.uk/deptprojects/index.htm . If you would like to enquire about support for a project, please contact the English

Subject Centre:

The English Subject Centre

Royal Holloway, University of London

Egham, Surrey TW20 OEX

T. 01784 443221 esc@rhul.ac.uk www.english.heacademy.ac.uk

2

“H

OW D O I R EFERENCE AN A RTICLE A GAIN

?”

I NFORMATION L ITERACY AND E-L EARNING

English Subject Centre Report on Mini-Project Funding

Dr Stacy Gillis, Newcastle University

(stacy.gillis@ncl.ac.uk)

March 2007

Much of the project research, the website construction and the writing of the assignments were done by the project assistant, Tom Theobald, under my guidance. The project simply would not have been completed without his hard work.

For anyone who is involved in the teaching and assessment of undergraduate students, the question of information literacy has become increasingly vital in the last ten years. Students arrive at university with an understanding and deployment of information literacy which often does not map onto the expectations of university learning strategies and assessment models. One of the primary elements of marking criteria is the measurement of the student’s ability to use library and web resources comprehensively and to reference these resources properly. Increasingly, however, students enter university with no experience of how to reference and, more importantly, no knowledge of why they should reference.

This has several implications for the business of teaching and assessing undergraduates:

Students do not understand or value engaging in academic research.

Students are more likely to plagiarise as a result of a lack of knowledge of what constitutes academic research.

Academic procedures are devalued.

Information illiterate students move into the workplace.

Students enter postgraduate studies without an appropriate level of research skills.

Students can have a disregard for other people’s intellectual property.

As a result of not meeting the marking criteria, students make lower marks.

Students find it difficult to engage in intellectual debate.

As a result of not making effective use of resources, students struggle to understand the reasons behind research.

In addition to this, the general rise in rhetoric and composition modules in the

US and Canada and in effective writing modules in the UK and Australia provides an informal indication that there is a widespread recognition that students are entering university without adequate writing skills. Some degree courses are still based around the idea that all students have these skills

3

when they enter university and much of the assessment for English Studies degrees – the essay – is based on knowing how to research and write.

1

While the larger question of the state of higher education is beyond the remit of this project, I am concerned with how much of valuable contact time is spent during the degree working with students on how to research and write.

Whose job is it to teach students how to do this? Is this the responsibility of the academic tutor, library staff or the study skills unit? Should this be built into all first-year modules? If schools and the National Curriculum do not promote these skills in a way which maps onto university expectations, should universities change their expectations? In short, if being able to research and write is part of our marking criteria, should we be teaching students to do this from scratch? How can and do we teach students to make the transition to being university-level researchers? These questions are part of the larger issue of information literacy. Students often enter universities with no sense of how to engage in the new economies of information which circulate and which they must learn – to varying degrees – how to assimilate whether they are going into the job market after graduation or going on to postgraduate studies.

This project originated in me putting down my pen during marking, having just corrected a student’s erroneous version of referencing an article in the MLA style. What made this more frustrating was that this was a student – and a good one – who I had taught the previous year and I had made the same corrections on the essay the previous year. Clearly my indicating the correct way to reference an article was not helpful enough to get the student to remember to do this again. This is not an isolated incident and I have had this experience with numerous students. My solutions to this have been varied: spending part of a seminar discussing research and writing tips; preparing a style sheet; looking at draft bibliographies; advising them to purchase a copy of The MLA Handbook . Yet none of this seemed to get the majority of students to engage with the vagaries of research and writing at a university level. As I thought more about the problem, it became clear that it is not just referencing which is a problem. Knowing how to reference properly is one indication of a scholarly student

– a student who is able to engage in a larger intellectual project. I wanted to find a way to help students to become scholarly students – from first entering the library to the final draft of the bibliography.

Face-to-Face Writing Skills vs Web-based Academic Research

Up until 2006, first-year students in the Department of English at Newcastle

University took the compulsory 10-credit weekly module Writing Skills . This

12-week module consisted of seminars on various topics, including how to use punctuation, how to reference, etc. It was taught by staff for the first four weeks and by graduate students for the remaining eight. Assessment was

1 For more on this see the Royal Literary Fund Report Writing Matters (2006), edited by Stevie Davies, David Swinburne and Gweno Williams Available online:

<http://www.rlf.org.uk/fellowshipscheme/documents/RLFwritingmatters_000.pdf.>

4

completely based upon a 1000-word essay submitted at the end of the module. The module was supported by a handbook which included examples of how to reference, how to construct a topic sentence, etc.

Undergraduate student resistance to the module was extremely high.

Feedback forms indicated, however, that the resistance was not to the content but to the form. Students felt that seminars were not an appropriate format in which to gain the sort of skills and knowledge upon which they were being assessed. A working party of students resolved that students were unhappy with the module for two reasons:

1. Not enough detail was provided on the skills necessary to succeed at university.

2. Seminar-based sessions were not appropriate for the attainment of these skills.

The proposed solution was a web-based module which would allow students to manage their own learning. Students would work through the hands-on assignments on the web, ensuring that they have actual experience of how to, for example, use a footnote properly. All students must have completed the module by the end of their first year and they would have access to the site throughout their degree, ensuring that they could return to the assignments and research content. The website would demonstrate a way in which students might gain these skills and be encouraged to take control of their own learning while also providing a much-needed link between A-level work and university study.

I renamed the module Academic Research as the Writing Skills title implied that students did not know how to write. While this may be the case, the renaming focuses on the proposed outcome of the module, rather than the possible shortcomings of the students. The aim of this project was to research and create a web-based module concentrating on research and writing skills. Evidence suggests that students generally want to become more information literate but are unsure how to achieve this. This web-based module would achieve this through on-line assignments which are undertaken in conjunction with library assignments. This would not be a website which supported an existing module. It would be an almost entirely web-based module for students who were enrolled in the School’s undergraduate degrees, undertaken in their own time, and the completion of which would be mandatory for progression to the following year. After attending the first two seminars with their personal tutors, students worked through a series of online assignments. For each of the nine units, students had to read through a short document and then work through a series of exercises. Some of these assignments required students to use the library while others required them to look critically at work they submitted for other modules.

There are situations in which a generic study skills module might provide interesting results: one might imagine how students in History and students in

Englis h might learn from one another’s approach to constructing an argument.

However, the administrative logistics of running this at the first-year level make it extremely unlikely to occur. Moreover, the danger in making a course too generic (as has occurred, according to informal discussion with colleagues

5

in other institutions, with some generic postgraduate study skills modules across the country) results in students not seeing the relevance of it to their own discipline. If students perceive the training to be germane to their degree work (and result!) then they will, for the most part, welcome it. This training in research and writing skills must be, therefore, relevant, efficient, easy to access and helpful.

Study Skills in English Departments

A survey of all English department websites in the UK revealed that most departments offer a first-year undergraduate module which incorporates some aspect of academic research and writing. Many of these modules include some or all of the following as required purchasing by students:

Hurford, James. Grammar: A Student’s Guide . Cambridge: Cambridge UP,

1994.

Aitchison, James. The Cassell Guide to Written English . London: Cassell,

1997.

Stott, Rebecca, et al , eds. Making Your Case: A Practical Guide to Essay

Writing . Harlow: Longman, 2001.

Stott, Rebecca, and Peter Chapman, eds. Grammar and Writing . Harlow:

Longman, 2001.

Crystal, David. Rediscover Grammar.

Harlow: Longman, 2004.

I use the phrase “required purchasing” rather than “required reading” because informal discussions with students and colleagues at various institutions indicates that while students often purchase these texts (and may intend to read them as directed) they rarely use them. The reasons for this are outside of the remit of this project but it is certain that students need instructive help in the acts of research and writing. Although several universities teach individual modules on these skills, most incorporate some material into the common first-year literary survey modules. All of these modules are taught through lectures and/or seminars.

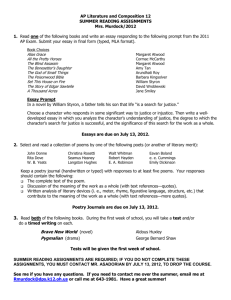

Below is a snapshot of available online material as of Autumn 2006. The below websites are not directly focused on students of English Literature and the advice can be generic on some. The list below does not includes those departments of English which have styles guides and handbooks in either

PDF or Word format, available for students to download.

University

Birkbeck

Birmingham

Brighton

Level

1

1

1

Module Title

Reading Literature

Literature Foundation

Website*

Cardiff 1

Structure and Grammar of

English & Text Design: Genre and Style

Reading Novels, Writing

Essays

Central

Lancashire

Dundee

1

1

Literature, Criticism and

Practice

Ways to Read & Ways to

6

Essex

Gloucestershire

Kent

Kingston

Lancaster

Leeds

Leeds Met

Leicester

Lincoln

Liverpool

Manchester

Newcastle

Plymouth

St Andrews

Stirling

Strathclyde

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

Manchester Met 1

1

1

Royal Holloway 1

Salford

Sheffield

1

1

1

1

1

Teesside

York

1

1

UW Aberystwyth 1

Wolverhampton 1

Argue

Writing Skills

Reading Literature, Practicing

Criticism

Critical Practice

Aspects of English

English 100 http://www.kent.a

c.uk/english/writin gwebsite/writing/i ndex.php http://www.lancs.

ac.uk/depts/engli sh/prospective-

Language, Text and Context ug/part1.htm

Skills for Advanced Learning

Approaches to Literature

Introduction to Literary

Studies

Close Reading

Reading Literature

Research Methods & Writing

Skills

Academic Research

Practice of Reading and

Writing

Critical Practice: Reshaping

English

Applied Study Skills

Introduction to Advanced

Literary Studies

Reading English Literature http://www.shef.a

c.uk/literature/ug modules/lit101.ht

ml http://www.standrews.ac.uk/ac ademic/english/u g/index.html

Author , Reader, Text &

Text and Context

Basic English

Critical Skills

Approaches to Literature

The Study of English

Writing for Academic

Success http://www.strath.

ac.uk/Department s/English/infoclas ses0405.html

7

* These websites are open access. Many of these modules had closed elearning environments attached to them which are only accessible to students and staff at that institution.

For the most part, assessment of research and writing skills across the discipline of English studies is still achieved through the traditional essay: we assess students implicitly in the skills of information-gathering, paragraph structure, referencing, grammar, etc, when we assign one mark for the whole essay. In this sense, current assessment of research and writing skills across the discipline does not differ from the essay-based assessment which forms much of the contemporary English literature and language degrees. The range of assessment on the specific modules listed above varies, although most are assessed through submitted essays which should display research and writing skills. Exceptions to the essay-based assessment are not common, although they do exist. At Salford, the module is assessed in various stages, including a Library and IT Skills exercise and a 500-word essay concerned with annotation, summary and paraphrase. Essex assesses, on pass/fail basis, “through worksheet tests (50%), written assignments (25%), and a reflective journal (25%)” and Leicester similarly incorporates a portfolio of exercises completed in workshops which are

“designed to bring students up to speed with the department’s required standards in essay writing, information technology and information handling, referencing and research methods.”

The aims and outcomes of the surveyed modules vary widely, although all share the common theme of introducing students to English studies. Many of the aims and outcomes of these modules are still embedded in the teaching of literary theory/history and the importance of research and writing skills is implicitly contained therein. For example, at St. Andrews, students on their module “develop the skills of close reading, of both prose and verse; an awareness of literary and linguistic change; an understanding of the relationships possible among author, text and reader; and a critical vocabulary for discussing these issues.” Similarly, at Sheffield, their first-year undergraduate module generally “provides students with an introduction to universitylevel thinking, studying, and writing.” Students gain “an insight into the importance of historical and cultural context in the shaping of literary meaning,” and, in addition, are equipped “with bibliographical skills (e.g. the use of library, IT facilities, secondary criticism) [to help] develop… research and writing skil ls.” While students can gain bibliographical skills in the process of researching and writing essays, this sort of approach is implicit rather than explicit as is evidenced by Liverpool: the purpose of the module there is “to foster and enhance the skills of close reading by drawing attention to what is needed to read texts attentively; to enable students to criticise and write focused critical essays on the basis of their attentive reading.” The teaching of these modules within the lecture/seminar format means that students rarely get a chance to engage with how to do research within the specific learning environment.

Some departments do offer modules which explicitly engage with research and writing skills. These are largely, although not exclusively, offered by post-

8

92 institutions, the student intake of which can differ, in terms of background demographics, from that of older institutions. Thus, for example, Teesside has a module which “supports transition to the degree level approaches required for English Studies courses bringing students together to work and reflect on the subject. Skills explored include: seminar discussion, group work, academic argument, information skills, conceptual and analytical skills and independent study.” Similarly, a module at Central Lancashire teaches students to “demonstrate a grasp of the mechanics and processes involved in producing a long, independentlyresearched essay.” Salford is much more explicit about what exactly is involved in the “study and research skills and strategies which are essential for developing… scholarly habits and ensuring

…good academic progress.” Their two-semester module introduces students to such “skills as annotating, summarising, and classifying – these are key skills for effective reading, note-taking, and research

– as well as library skills,

IT skills, and essay writing basics: how to construct a good introduction and conclusion; how to use references and construct a bibliography; and so forth.”

These sorts of modules explicitly provide the necessary examples of, for example, how to reference a website, which students can struggle to absorb through the traditional route: a sink-or-swim immersion in the library.

However, these modules do not provide students with multiple opportunities to explore how to, for example, search for an article on FirstSearch. As these modules are locked into the lecture/seminar format, students are still passive learners, waiting for appropriate information to be given to them.

What Do Students Need to Know?

Focus groups with upper-level students at Newcastle, interviews with colleagues, and reviews of the above books and websites resulted in the following list of information which students need to know in order to become scholarly students:

Effective Reading and Research :

summarising

taking notes (direct quoting & paraphrasing)

distinguishing between sources (i.e. primary, secondary, introductory textbooks & overviews)

essay planning

Resources :

finding and accessing different formats in the library (journals, collection, student texts collection)

using online resources (MUSE, LION, etc) in the catalogue.

Grammar :

punctuation (commas, colons)

apostrophes

‘hanging participles’

using subordinate clauses.

9

Writing Style :

tense (i.e., the difference betw een the ‘universal’ present tense of textual analysis and past tense when writing biographical information about the author)

use of the passive form

use of the ‘I’ and addressing the reader

ways to avoid overt repetition

academic vocabulary

Essay Structure :

use of paragraphs (length, coherence, structure, linking)

general structure (i.e. a section on each of the main parts of an essay: introduction, middle, conclusion)

tips on structuring a coherent argument while sticking to the question

writing drafts

topic sentences

Referencing and Quoting :

differences in the referencing of different sources (book, journal article, collection, website, poem)

how to quote (footnoting, use of quotation marks, length of quote, paraphrasing)

when & what to quote (i.e. problems of over-quoting, using unreliable sources, quoting from study guides, quoting lecture notes)

plagiarism

writing a bibliography

Design of the Project Website

Because the module was going to form part of the assessment for some 300+ students and because it was a component of their mandatory work, it had to be housed within the Blackboard e-learning environment. Blackboard would also be able to manage the online submissions and keep track of the marks allocated by the markers. However, this meant that the project was, from the outset, confined by the limits of what Blackboard can do.

The site consisted of five components, the titles of which were somewhat conscribed by the university’s chosen Virtual Learning Environment,

Blackboard: Announcements; Module Information; Learning Units; Web

Resources; and, Discussion Board.

Announcements

In addition to reminders about deadlines posted by tutors, the following permanent announcement was displayed:

10

You must complete all and pass at least 50% of the assignments before you can submit the final essay for this module. Your final essay mark is your overall mark for Academic Research .

As you work through the nine units, you will be either acquiring or refreshing your acquaintance with the skills and knowledge which you require to make you a successful academic researcher. You may feel that you already know everything you need to know to be a successful academic researcher - but we know from years of marking essays and exams that most undergraduate students need this help. If you think that you already know all the information here then we look forward to you receiving 100% - and if you do not, what you learn here will help you with your research and writing for the rest of your degree.

Module Information

Aims

To allow students to practise writing across a range of different

registers and styles of writing and, focusing on academic writing, and to become more reflective about writing styles.

To enable students to become more effective academic researchers.

To introduce students to university-level research and writing.

Outcomes

Students will be able to:

Recognise what constitutes effective academic writing.

Identify and use effective and accurate presentation of academic

essays.

Write in different styles and registers.

Present academic essays in a clear and accurate way.

Use the full resources of the library and the web.

Recognise the importance and viability of being an academic researcher.

These skills and knowledge will help you throughout your degree, enhancing your essay, presentation and exam results. These skills are also transferable to the job market as they will enhance your written and oral communication skills and your ability to make an effective argument.

Note on the Submission of Assignments

All the assignments will be released at 9.00 on October 16th. You have until

17.00 on December 15th to complete the assignments. As of 5.00 on that day, any uncompleted assignments will be marked as a Fail.

The essay titles will be released at 9.00 on December 4th. Your entire mark for this module is based on this essay. Essays are to be submitted electronically by 5.00 on January 15th. Late essays will be penalised.

The majority of the assignments you submit for this module will be in Word format. Please note the following:

11

Before you submit your files, make sure that you use the ‘save as’

function, rather than simply clicking on ‘save’.

The format for the file names should look as follows: ‘first name_surname_name of assignment.doc’. For example, if John Smith submits assignment 1 on academic research, the file name should be

‘John_Smith_assignment1.doc’.

It is your responsibility to submit the assignments on time and with the proper file name. Files submitted without the proper file name will not be marked.

You also must write your full name within the Word document itself.

Always keep copies of your submitted files for yourself.

Learning Units

Each of the following units contained a short document to read and an assignment to complete.

Introduction to Academic Research

Essay Planning

Library Resources

Web-Based Research

Referencing and Bibliographies

Paragraph Structure

Essay Structure

Grammar and Punctuation

Writing Style

See Appendix A for further documentation from each of these units.

Web Resources

In addition to links to the databases available through Newcastle University’s library, the website contained links to the following sites:

Project Muse: Literary Journals (http://muse.jhu.edu/journals)

JSTOR: Literary Journals (http://uk.jstor.org/)

Literature Online (http://lion.chadwyck.co.uk/)

Voice of the Shuttle (http://vos.ucsb.edu/)

BL Online: The Bibliographical Database of Linguistics

(http://www.blonline.nl/)

Linguasphere: Online Database

(http://www.linguasphere.com/)

BUBL Information Service (http://bubl.ac.uk/)

Intute: Arts and of Languages

Humanities

(http://www.intute.ac.uk/artsandhumanities/)

The Internet Public Library (http://www.ipl.org/)

Skaldic Editing Project (http://skaldic.arts.usyd.edu.au/db.php)

Labyrinth Resources for Medieval Studies

(http://www.georgetown.edu/labyrinth/labyrinth-home.html)

12

University of Delaware Library

(http://www2.lib.udel.edu/subj/)

Academic Info: Educational

Subject

Subject

Guides

Directory

(http://www.academicinfo.net/)

The Literary Encyclopedia (http://www.litencyc.com/)

Oxford English Dictionary (http://www.oed.com)

We made the decision to not inundate the students with a range of websites.

We wanted them to gain critical skills in using the Web as a research tool and to gain confidence in using a small number of helpful websites. Each learning unit also contained a small list of websites which were directly relevant to that topic.

Discussion Board

Discussion strands for each of the learning units were created on Blackboard and students were encouraged to use this in order to communicate with one another. Not surprisingly, they chose not to do so. Students usually tend to use a discussion forum when it is clearly linked to seminar/lecture-based assignments.

2

Students met with their personal tutors for the first two weeks of the module, engaging in general discussions about the nature of research, the study of

English at university and learning about the requirements of the seminar/lecture/tutorial spaces. They also had two introductory lectures showing them how to use the website. Because of timetable constraints for a lecture group of this size (300+), these had to be in the week before the semester started. This was problematic in that most students had not yet had their introduction to Blackboard – indeed, most of them had not even logged into Blackboard yet. This made the introductory lecture rather abstract for most of them. It also meant that I had a steady stream of students coming to my office throughout the semester asking for help in logging in. There were also a small number of students who were resistant to the idea of e-learning and who complained vociferously about having to use computers. The majority of students, however, quickly learned how to use Blackboard.

The summative assessment for the module was based 100% on a final essay of 1500 words which had to display knowledge of the material covered in each of the learning units.

3 That is, the marks were allocated on the basis of the

2 For a full discussion of these issues see Rosie Miles, “Research, Reflection and Response:

Creating and Assessing Online Discussion Forums in English Studies,” English Subject Centre Newsletter 12

(April 2007): 32-5.

3 The essay topics were as generic as possible. Students had to answer one of the following, using texts from other modules studied that semester:

Rubric: The point of this essay lies in applying the various academic skills discussed over the course of this module. As such, you will not be marked on essay content and ideas. You must reference at least ten sources, which, besides the obvious monographs, should include essays from edited collections, online articles and journal articles. You will have to choose one referencing system and stick to it rigorously. You will be marked on your bibliography, footnotes and in-text references. How you paraphrase and introduce quotations will also be taken into consideration, as well as essay structure and paragraph structure. Your writing style, use of punctuation, and grammar will also affect your final mark.

13

nine learning units and the students’ demonstrated grasp of the material therein – the students were not marked in terms of the content of the essay except in insofar as it impacted on the essay structure. Students, however, could only proceed to this assessment if they had completed all of the formative assessment – the online assignments – and passed at least half of them. All the online assignments had to be completed by December 15 th – students could choose to do all the assignments in the first week or the last as it was entirely up to them. The assignments were marked and returned by the postgraduate markers within two weeks. Students were informed in December if they had passed the formative assessment and could proceed to the final essay (due at the end of January). Some students realised that if they passed half the assignments then they could do poor work on the other assignments

– failing them – and still proceed to the final essay. Still others clearly made the strategic decision to not do any of the assignments, thereby failing the module. The re-sit assessment for this module is a 2500 word essay

– meaning that they have to write a longer essay in exchange for not doing any of the assignments. Some of the students came to me asking, in effect, my permission as convenor to do so (not given…). There were also several incidences of plagiarism: some students submitted online assignments that still had other people’s names in the Word document titles.

In total, there were 46 fails (out of 305 students). Of these, 3 failed the final essay. Very few students failed the submitted assignments. The majority of those who failed either did not submit any assignments or plagiarised (which was an automatic fail). Discussion with the failed students indicated that none failed because of difficulties with using Blackboard – they either chose not to do it or left it too late. This extremely high rate of failure is a matter of some concern. It should hopefully be adjusted in future years through remodelling the assessment deadlines. In future years, there will be three points of submission throughout the semester. Students will have to pass two out of three of these submissions and will not be informed until the end if they have passed. Assignments will also be marked on a pass/fail basis – this year the postgraduate markers gave numerical grades and these could fluctuate widely. The re-sit loophole has been closed

– the re-sit exam is now a twohour exam on grammar and syntax and this will be clearly stated at the outset.

Having to use Blackboa rd posed its own challenges. It is very “click-heavy” for those designing and maintaining the site

– the navigation of its Control

Panel required a good working knowledge of e-learning environments. We had initially hoped to use the online assessment facilities of Blackboard in more detail but because of the restrictions of the e-learning platform, we had to get students to submit their assignments in Word files. These were saved in Blackboard and accessed by the postgraduate markers. The postgraduate markers all commented that most of their marking time was spent on opening the student files (which requires a great deal of clicking through pages) in

Literature Students: Discuss the representation of gender, class OR race in two texts you have studied this semester.

Language & Linguistics Students: Discuss an aspect of either the historical development of English or the structure of English (Make sure to mention at least 2 lingustic expressions).

14

order to download the information. One of the priorities for next year is the streamlining of site in order to assist the postgraduate markers – this will mean students will submit three bunches of assignments. Confusion also resulted when students did not put their names on their submissions. This meant laboriously tracing who had submitted what document. This has been resolved by the creation of a submission sheet – assignments submitted without the sheet will not be marked. There were also some minor teething problems in that this module has both Literature and Language & Linguistics students which meant creating different assignments for the different streams.

Keeping track of which student had submitted what proved occasionally tricky for some of the postgraduate markers. In future, a general database will be managed by the convenor in order to keep track of submissions.

Final Thoughts

For those of us involved in the teaching of undergraduates, it has become increasingly obvious since the late 1990s that e-learning and flexible learning strategies are key elements to consider when planning a syllabus. Indeed, the

Government’s White Paper, The Future of Higher Education

(http://www.dfes.gov.uk/hegateway/strategy/hestrategy) referred to “more flexibility in courses, to meet the needs of a more diverse student body.” While the government is broadly concerned here with the Widening Participation agenda, notions of flexibility in terms of student learning have been coming increasingly to the front of the agenda (see also http://www.hefce.ac.uk/learning/flexible). This in turn links with e-learning which, for some years, has carried the burden of key innovation in pedagogic strategies. The HEFCE Strategy for E-Learning

(http://www.hefce.ac.uk/learning/elearning), outlines a ten-year strategy to

“integrate e-learning into higher education,” intending “to enable all universities and colleges to make the best use of information and communications technologies in their learning and teaching.” The

Academic

Research website brings together these two strands, introducing students to the use of e-learning in higher education while allowing them a flexible approach to their learning patterns.

The creation and first year of Academic Research operated as a pilot project in Autumn 2006 with funding for the project assistant provided by the English

Subject Centre

– for which, many thanks! The response to the site from staff was reasonably positive although some were reluctant or unable to access the website. Student response varied. The site had a 14-member strong

Facebook site called “I hate Academic Research with a firey [sic] passion.”

The tagline ran as follows: “All English students.. I’m sure you all feel the same way... What. Is. The. Point?!” Official student feedback, however, indicated that they found the site both helpful and relevant (although student feedback does tend to be self-selecting). Students particularly noted being able to choose when to complete the assignments and the relevance of the material placed on the website. Whether or not the completion of the module will have a long-term impact on their upper-level essay marks remains to be seen. We hope to return to the same group of students at the end of their

15

degrees and ask for feedback on the module in the context of all their degree work.

The School is committed to maintaining this module as part of the undergraduate provision although the ongoing maintenance of the website is a question to be considered each year. I offered support for this website and convened the module. However, running the website and the module (not always the same thing) will not be part of my teaching load each year.

Subsequent convenors will have to possess a degree of e-learning knowledge in order to engage with the website in a meaningful way and this constricts the number of individuals who might take the job on. These are matters to be generally considered when considering implementing e-learning into the syllabus. Finally, this was a very heavy load for the convenor in terms of administration. I received an average of 60 emails a week for this module

– all of which required me to explain something to a student (usually about how to submit an assignment or clarifying one of the assignments). Pre-empting as many of these requests as possible will require substantial re-jigging of the site and the construction of an FAQ. The site will require substantial revision before it can run again and the cost of employing someone is a cost to consider. These sorts of substantial revisions to team-taught modules should not fall to the convenor as they comprise a heavy administrative burden which can often go unacknowledged. These sorts of revisions do, however, offer excellent employment and experience for postgraduates.

I do not consider this project to have ended

– each year the site and the module will need to be adjusted and maintained. The long-term impact on student essays remains to be seen although informal discussions with colleagues indicate that the first-year essays have been uniformly strong this year. E-learning and flexible learning are both here to stay, as are the challenges posed by students entering with little knowledge of the demands of university-level information literacy.

16

![Submission 68 [doc]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008000926_1-fed8eecce2c352250fd5345b7293db49-300x300.png)