NUOVO CINEMA PARADISO Cast & Credits Italy, 1988 Running

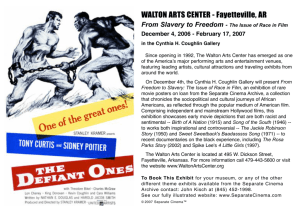

advertisement

NUOVO CINEMA PARADISO Cast & Credits Italy, 1988 Running Length (original): 2:03 Running Length (director’s): 2:54 Cast: Philippe Noiret (Alfredo), Salvatore Cascio (Salvatore “Totò Di Vita-Child), Marco Leonardi (Salvatore “Totò Di Vita-Younger), Jacques Perrin (Salvatore “Totò Di Vita – Adult), Antonella Attili (Maria Di Vita – Younger), Pupella Maggio (Maria Di Vita – Older), Agnese Nano (Elena Mendola - Younger), Leopoldo Trieste (Father Adelfio), Brigitte Fossey (Elena Mendola – Adult), Isa Danieli (Anna), Leo Gullotta (Usher) Director: Giuseppe Tornatore Screenplay: Giuseppe Tornatore Cinematography: Blasco Giurato Editor: Mario Morra Art Director: Andrea Crisanti Music: Ennio Morricone Produced by: Cristaldi Pictures/Films Ariane/Forum Pictures/RAI 3 Release: 1988 11.17(Italy)/1990 02.02(USA)/2002 06.14(USA-Limited-Director’s Cut Re-release) Released by: Titanus Produzione U.S. Distributor: Miramax Films Color type: Eastmancolor Box office: $11,990,401 Set in:1940s, post-World War II Genre/Type: Drama/Melodrama Plot Synopsis Cinema Paradiso offers a nostalgic look at films and the effect they have on a young boy who grows up in and around the title village movie theater in this Italian comedy drama that is based on the life and times of screenwriter/director Giuseppe Tornatore. The story begins in the present as a Sicilian mother pines for her estranged son, Salvatore, who left many years ago and has since become a prominent Roman film director who has taken the advice of his mentor too literally. He finally returns to his home village to attend the funeral of the town's former film projectionist, Alfredo, and, in so doing, embarks upon a journey into his boyhood just after World War II when he became the man's official son. In the dark confines of the Cinema Paradiso, the boy and the other townsfolk try to escape from the grim realities of post-war Italy. The town censor is also there to insure nothing untoward appears onscreen, invariably demanding that all kissing scenes be edited out. When the old Cinema Paradiso is burned down, and Alfredo blinded in the process, Salvatore becomes the projectionist of the Nuovo Cinema Paradiso. However, he doesn't know how to edit the films as the local clergy wish, so the town finally gets to see all the sexy parts in modern cinema. A few years later, Salvatore falls in love with a beautiful girl who breaks his heart after he is inducted into the military. Thirty years later, Salvatore has come to say goodbye to his life-long friend, who has left him a little gift in a film can. In 2002, over a decade after the film's original release, Tornatore brought the original 170-minute director's cut to American screens for the first time. NOTES ABOUT THE FILM DIRECTOR Biography Born in Bagheria near Palermo, Giuseppe Tornatore (born 27 May 1956) Tornatore showed interest in theatre and acting well from the age of 16. He then switched to cinema, making his debut with a documentary movie called Le minoranze etniche in Sicilia (Ethnical minorities in Sicily), which won a Salerno Festival prize. He then went on working for RAI, before releasing his first full-length movie, Il Camorrista, in 1985. However, Tornatore's best known screen work was released in 1989: Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, a movie about the return of a successful film director to his native town in Sicily for the funeral of an old friend of his, obtained worldwide success and won an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Following the success of Nuovo Cinema Paradiso, Tornatore released several other movies, his latest in 2006, but never repeating the success of his most successful work. Filmography Il Camorrista (1985) Nuovo Cinema Paradiso (1989) Everybody's Fine (1991) Especially on Sunday (1993) (segment "Il cane blu") A Pure Formality (1994) The Star Maker (1995) Lo schermo a tre punte (1995) (documentary) Ritratti d'autore: seconda serie (1996) (documentary) The Legend of 1900 (1998) Malèna (2000) La Sconosciuta (2006) As a screenplay writer Cento giorni a Palermo ("Cent jours à Palerme"), directed by Giuseppe Ferrara (1984) quoted as Peppuccio Tornatore THEMES LOVE FOR MOVIES The film is a celebration of the love of not only the movies, but the movie theatre in general. Out of that love comes a friendship between a film projectorist and a boy who shared a passion for movies. The film tells of a movie palace in a small Italian town, where people come to see films. We see how the lives of the people are transformed because of their love for movies. THE ROLE OF THE CINEMA IN POST-WAR IMAGINARY Cinema Paradiso is not just about the relationship or tragedy of Toto and Alfredo. It's about the loss of a whole culture, a whole era - a time when movies and distribution weren't calculated, homogenized and marketed to death, and when the people who showed and watched them loved them madly. Cinema Paradiso is essentially an ode to life’s two most important passions: romantic love and career. The setting of the story is in Sicily following WWII when the big screen was at the center of the entertainment industry, just before the advent of television. And it's the overall, dreamy effect, that makes the otherwise ludicrous believable, such as the time Alfredo tempers the unruly mob crowded out of the Paradiso by reflecting the film onto the white wall of a house, so that everyone can see the movie. When Salvatore-the movie aristocrat- watches, in a modern screening room, the last gift given to him by his old peasant-worker friend, it's a moment of epiphany that goes beyond sentimentality. It's a flood of passion, a collage of tenderness. It suggests the moment when cinema, released in the dark, almost becomes paradise. THE FILMS OF ITALIAN NEOREALISM If the viewer could sit still for 7 hours in a row, Cinema Paradiso might make an interesting double-bill with Martin Scorsese's new four-hour documentary on the history of Italian film, My Voyage to Italy. Both films include clips of many of the same movies: Visconti's La Terra Trema, Fellini's I Vitelloni, etc. Director Tornatore uses his slightly-stylized techniques to lend a quality of magic realism to some scenes, such as the carved lion projector port that comes alive in one dramatic scene. We see many film clips projected on the Paradiso's old screen, familiar Italian classics like La Terra Trema and Il Grido, and many (public domain) American titles - It's a Wonderful Life, Stagecoach. Anyway, Tornatore doesn't play games with film history, and the titles help film fans keep the chronology of the movie straight. Both films go a long way in describing the affection we can develop for movies. And though many movies become memories, they can easily be re-visited and become the present day again, thereby avoiding the trap of nostalgia. CENSORSHIP The Screen Kiss is important to Cinema Paradiso. Early in the film, the local priest previews each movie before it is available for public consumption, using the power of his office to demand that all scenes of kissing be edited out. By the time the new Paradiso opens, however, things have changed. The priest no longer goes to the movies and kisses aren't censored. Much later, following the funeral near the end of Cinema Paradiso, Salvatore receives his bequest from Alfredo: a film reel containing all of the kisses removed from the movies shown at the Paradiso over the years. It's perhaps the greatest montage of motion picture kisses ever assembled, and, as Salvatore watches it, tears come to his eyes. The deluge of concentrated ardor acts as a forceful reminder of the simple-yet-profound passion that has been absent from his life since he lost touch with his one true love, Elena. It's a profoundly moving moment -- one of many that Cinema Paradiso offers. STEREOTYPES Despite his crowding of the film with familiar Italian-character cutouts (screaming parents, admonishing priests, masturbating boys and, yes, even a town idiot), screenwriter/director Tornatore gives these and other cliches an entertaining flow, a certain Mediterranean deliriousness. The movies brought not only the world but the future to the bucolic town of Giancaldo, whose citizens jeered and wept, swooned and spooned, spat and smoked and picked their noses, drank Chianti and nursed their babies, married and even died at the Cinema Paradiso. Over the 40 or so years of the story, the theater itself undergoes many transitions, so the gently comic film not only celebrates but eulogizes the community and the picture show. THE WORTH OF MEMORY Most of Cinema Paradiso is told through flashbacks. As the film opens, we meet Salvatore (Jacques Perrin), a famous director, who has just received the news that an old friend has died. Before departing for his home village of Giancaldo the next morning to attend the funeral, he reminisces about his childhood and adolescence, thinking back to places and people he hasn't seen for decades. Tornatore displays such skill in the way he excites our emotions that we don't care. This film is sometimes funny, sometimes joyful, and sometimes poignant, but it's always warm, wonderful, and satisfying. Cinema Paradiso affects us on many levels, but its strongest connection is with our memories. We relate to Salvatore's story not just because he's a likable character, but because we relive our own childhood movie experiences through him. Who doesn't remember the first time they sat in a theater, eagerly awaiting the lights to dim? There has always been a certain magic associated with the simple act of projecting a movie on a screen. MOVIES “ INVADE” THE CHARACTERS’LIVES Tornatore's most unique element in his story (which is largely autobiographical) is the parallel between the evolution of cinema and the experiential growth of his characters. The camera captures the essence of the villagers' lives through vignette-like clips. A particularly memorable one is of a couple who begin their romance with a glance from the balcony to the floor seating in the Cinema Paradiso - we later see them cozily seated together during their courtship, and later again with their squalling child in the theater. At the end they reappear as an elderly couple and silently acknowledge the role that Salvatore played in bringing them together. Some moments are more heavy-handed than others, such as the end sequence, when the demolition of the Cinema matches the crumbling of the aging Salvatore's dreams a little too zealously. CHILDHOOD VISIONS Tornatore prefers to see the world through a child’s eye, where some of the harsh realities of life are filtered out. Cinema Paradiso is somewhat true-to-life story about the Italian director’s youth at the end of World War II in a tiny Sicilian village, where the town movie theater served as school, public square, lovers’lane and refuge from oppressive poverty. THE NECESSITY OF COMING OF AGE But Alfredo realizes that in order for Salvatore to grow and fully reach his potential, he must leave the village and its humble quaintness. The love between the two climaxes when Toto boards the train for Rome and Alfredo commands him to never return, never look back. Salvatore's education began with exposure to the world through films- to continue developing, he must now enter that world, not simply observe it on the screen. KEYWORDS Boy, censorship, filmmaking, flashback, friendship, movie-theater, projectionist, village, childhoodadventures, coming-of-age MEMORABLE QUOTES Alfredo: [after informed about the arrival of the new non-combustible film] Progress always comes late. Alfredo: Living here day by day, you think it's the center of the world. You believe nothing will ever change. Then you leave: a year, two years. When you come back, everything's changed. The thread's broken. What you came to find isn't there. What was yours is gone. You have to go away for a long time... many years... before you can come back and find your people. The land where you were born. But now, no. It's not possible. Right now you're blinder than I am. Salvatore: Who said that? Gary Cooper? James Stewart? Henry Fonda? Eh? Alfredo: No, Toto. Nobody said it. This time it's all me. Life isn't like in the movies. Life... is much harder. Alfredo: Once upon a time, a king gave a feast. And there came the most beautiful princesses of the realm. Now, a soldier, who was standing guard, saw the king's daughter go by. She was the most beautiful one, and he immediately fell in love with her. But what could a poor soldier do when it came to the daughter of the king? Well, finally, one day, he managed to meet her, and he told her that he could no longer live without her. The princess was so impressed by his strong feelings that she said to the soldier: "If you can wait 100 days and 100 nights under my balcony, then at the end of it, I shall be yours." Damn! The soldier immediately went there and waited one day. And two days. And ten. And then twenty. And every evening, the princess looked out of her window, but he never moved. During rain, during wind, during snow, he was always there. The bird shat on his head, and the bees stung him, but he didn't budge. After ninety nights, he had become all dried up, all white, and the tears streamed from his eyes. He couldn't hold them back. He no longer had the strength to sleep. All that time, the princess watched him. And on the 99th night, the soldier stood up, took his chair, and went away. Salvatore: [later in the film, Toto gives Alfredo his interpretation] ... In one more night, the princess would have been his. But she also could not possibly have kept her promise. And it would have been terrible. He would have died. This way, however, at least for 99 days, he was living under the illusion that she was there, waiting for him.