Cultural Challenges in Cross

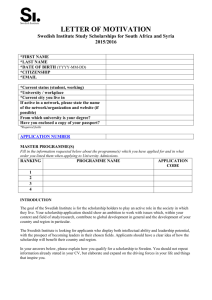

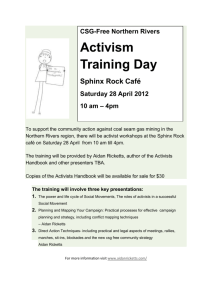

advertisement