Classics 2 - The Louisville Orchestra

advertisement

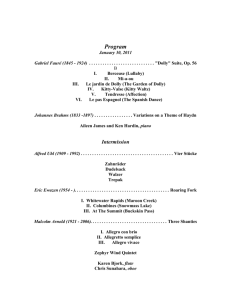

FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN Symphony No. 82 in C Major, Hob.I:82, The Bear Vivace Allegretto Menuetto Finale: Vivace DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No. 10 in E Minor, Op. 93 Moderato Allegro Allegretto Andante—Allegro Program notes by Rebecca Jemian The two pieces on today’s concert are both symphonies—multi-movement works for orchestra—but of two entirely different casts. Haydn’s symphony dates from the age of enlightenment, when the form was new and being standardized. Shostakovich’s work, composed in the post-Stalin Soviet era, treats the form with greater flexibility, resulting in a pensive and dramatic piece. FRANZ JOSEPH HAYDN Born March 31, 1732, in Rohrau, Lower Austria Died May 31, 1809, in Vienna Symphony No. 82 in C Major, Hob.I:82, The Bear I. Vivace (Lively); II. Allegretto (Moderately Fast); III. Menuetto (Minuet); IV. Finale: Vivace (Finale: Lively) The ever-inventive Haydn worked most of his professional life for the noble Esterházy family. The first five years were at their Eisenstadt estate, and, from 1761 until 1790, he was located at their grand palace Eszterháza. Sometimes referred to as “the Versailles of Hungary,” this home was located seventy miles from Vienna. Haydn commented that the remoteness of the location forced him to become original and independent. The terms of his employment changed over the nearly four decades of their contract. Combining such job security with the abundant musical resources provided by his employers and his innate creativity afforded Haydn ample opportunity to develop his style. The Symphony no. 82 was composed in 1786. Haydn’s earliest job description was “to compose and direct instrumental music for the princely court, together with some church music, and from time to time to compose and perform an opera.” A glorious theater was built in 1776 for more opera staging, and his duties adjusted to provide more original music as well as to oversee all the productions of the theater. In order to fulfill these expectations, Haydn was required to travel more frequently to Vienna to hire singers. Such duties cut into his available time for composition. A new employment contract of 1779 gave Haydn control and ownership over publications of his compositions, and this encouraged him to respond more favorably to outside requests. He gave up composing operas in 1783-84 and focused his writing on instrumental music. His Symphony no. 82, nicknamed “The Bear,” was part of a commission for six symphonies composed for the Concert de la Loge Olympique, in Paris. The symphony’s key, C Major, is often cited as a “festive” key used by composers for works with a celebratory feeling. This description amply fits this work and achieves its goal through high rhythmic energy and the instrumentation—trumpets and horns creating a jubilant sound. The slow movement is a graceful set of double variations with some charming touches of instrumental scoring. The Menuetto offers abundant motivic contrast between instruments, and its trio shows off the oboe and bassoon. The nickname, “The Bear,” was not given to this symphony until after Haydn’s death, and its cause is revealed in the Finale. The opening idea, which recurs throughout the movement, is a pedal tone, frequently preceded by a grace note, and this imitates the sound of the bagpipe. Bagpipes were the traditional instrument used to accompany dancing bears, typical entertainments at fairs in this period. So, the movement is called “The Bear” because the style is reminiscent of music used for dancing bears. Haydn scholar, Jens Peter Larsen comments, “The Paris commission seems to have arrived at just the right moment for Haydn, as a challenge. His work in Eszterháza was approaching a state of humdrum routine. In the works composed for publishers, like piano trios, sonatas or songs, he could—and did—excel in fine craftsmanship; but such pieces allowed only limited opportunities for novelty. The Paris symphonies, on the other hand, are so personal and original that it is immediately clear that Haydn was setting out again to create something entirely his own.” Haydn’s Symphony no. 82 is scored for flute, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, timpani and strings. It lasts approximately 25 minutes. DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Born September 25, 1906, in St. Petersburg, Russia Died August 9, 1975, in Moscow Symphony No. 10 in E Minor, Op. 93 I. Moderato (Moderate); II. Allegro (Fast); III. Allegretto (Moderately fast); IV. Andante—Allegro (Moderate—Fast) The Symphony no. 10 by Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich has an odd pacing in which the 25-minute first movement is longer than the other three movements combined. Shostakovich composed this work in the months after Joseph Stalin died; these months were pivotal as the end of a horrific totalitarian regime gave way to what many artists felt to be a thaw in the cultural climate. The symphony both figuratively and literally contains the composer’s musical signature. Shostakovich plays an important role in Soviet musical history because he is the most prominent composer who lived entirely in the Soviet era. He received his formal musical education after the 1917 Revolution to overthrow the tsar and lived the rest of his life in the USSR under the rule of the communist party. He died well before the end of the USSR in 1991 was considered a possibility. The two great musical centers of Russia have been Moscow and St. Petersburg (whose name changed to Petrograd and then to Leningrad during the twentieth century). Shostakovich grew up in St. Petersburg and, although he did not study directly with famous Russians—Rimsky-Korsakov had died in 1908, Stravinsky left the homeland in 1910, and Prokofiev finished his conservatory studies just a couple of years before Shostakovich began—he had lessons with Maximilian Steinberg who had worked with Rimsky-Korsakov himself. Shostakovich was an accomplished pianist as well as composer and helped support his mother and sisters after his father’s death by playing for silent movies. Strongly patriotic, Shostakovich lived in a time when his country’s politics were constantly undergoing change. The government instituted cultural committees who decreed standards for the arts, including music composition. The state promoted an artistic style called Socialist realism which dictated that art must be understandable by the common man, art should be representative of real things rather than abstract, art should support the aims of the state and the communist party, and the subjects of the art should be drawn from everyday life. As the Soviet party changed, the demands for Socialist realism were enforced with varying amounts of rigor. Artists who were found to be out of compliance were punished, not infrequently at the cost of their lives, especially during the term of Joseph Stalin, who led the country from 1924 to 1953. When the communist party charged a composer with formalism, it meant that the composer’s music was not adequately following the guidelines of Socialist realism. Shostakovich dutifully tried to balance the party’s aesthetic vision with his own artistic views. However, twice in his life he was publicly reprimanded in ways that could have had dire consequences. The first was in 1936 after Stalin and other prominent party members took offense at one of Shostakovich’s operas. The second time was in 1948 and was directed to a group of composers. Shostakovich apologized and thanked the party for pointing out his waywardness; he then adjusted his style by simplifying his musical language and turning his attention to movie music and vocal pieces which could deliver a clear patriotic message through their texts. He also did two other things: he withheld several pieces that might have been found faulty and he held his breath for his life and those of family and close friends. Stalin’s death in March 1953 (coincidentally on the same day as Prokofiev’s death) signaled an end to the worst times of creative oppression; many pieces could now be brought out for performance, and Shostakovich felt that he could write others that previously might have been censured. He composed the Symphony no. 10 in 1953, and it was first performed in Leningrad on December 17, 1953, Moscow. This somber work followed the witty and bright ninth symphony written in 1945—before the 1948 reprimand—that marked a successful conclusion to World War II. A serious beginning sets the tone for the first movement which winds up gradually. A contemplative clarinet solo quotes a passage from Mahler’s second symphony before the orchestra returns to a more hopeful version of some of the opening themes. Then a flute solo inaugurates a theme that is taken up across the orchestra and reprised in the solo bassoon. The movement is not given to sections with discrete edges, but instead is episodic and interwoven. The drawn-out coda is notable for an expressive piccolo duet. In stark contrast to the laborious unfolding of the first movement, the second movement whips by with great speed. This scherzo in the style of a galop is both sardonic and grim, and the driving music is joined toward the end by more somber themes. Michael Steinberg writes, “For something so intense, this movement is as long as is manageable or even tolerable without introducing a major contrasting section, and such a contrast would only weaken the effect of this terrifying outburst.” The third movement also has scherzo ambitions with its fast triple meter and flippant attitude. However, its structure has more drama than the typical scherzo. The rapid motion is interrupted by an unaccompanied horn whose intense call spreads wide across the piece. The return of the opening theme in the English horn is marked by an eviscerated accompaniment. As the movement continues, the musical ideas coalesce into a single motive of the pitches D, E-flat, C, B. The German names for these four pitches are D-S-C-H, and those represent the composer’s signature, for Dmitri SCHostakovich. This piece marks the first of many compositions in which he would sign his name using these pitches. The cello and double bass sections offer a thoughtful opening to the last movement, leading to a plaintive oboe solo (reminiscent of one in the fifth symphony). Then, a perky clarinet motive ushers in an almost manic section that drives incessantly throughout the movement. The D-S-C-H motive is stated forcefully as the symphony concludes with a march. Steinberg again writes, “Here is one of the most brilliantly vivacious of his Haydn finales, though it finds room for fleeting and always touching moments of a darker, sadder music.” Following the first performances of the symphony, critics began to debate the piece. Boris Schwarz notes, “The hard-line opposition maintained that the work was ‘non-realistic’ and deeply pessimistic in approach, but in the end the liberal faction won with the slogan that the new symphony was ‘an optimistic tragedy’.” Even now, scholars continue to debate the influence of the politics of Shostakovich’s time on his compositional output. Schwarz writes, “When forced on to the defensive, he did not argue; but through the strength of his genius he overcame the limitations of Socialist realism to the point where it no longer inhibited free musical creation, in the battle for which it was Shostakovich who ultimately emerged victorious.” The orchestra for Shostakovich’s Symphony no. 10 includes 2 piccolos, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, E-flat clarinet, 2 clarinets, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, triangle, cymbals, tambourine, tam-tam, snare drum, bass drum, xylophone and strings. The work lasts between 50 and 55 minutes.