- Digital Education Resource Archive (DERA)

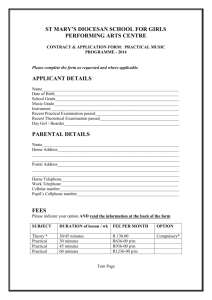

advertisement