CHAPTER III

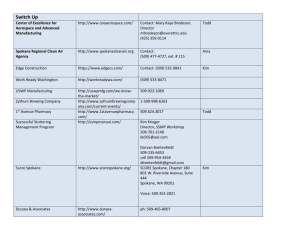

advertisement