last weeks case – inotropes and vasopressors

advertisement

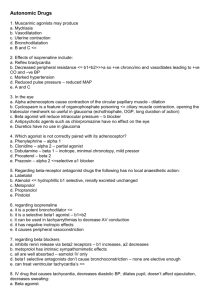

EMERGENCY MEDICINE Liverpool Hospital The Weekly Probe 26th February 2013 Volume 16 Issue 4 LAST WEEKS CASE – INOTROPES & VASOPRESSORS SINUSITIS LAST WEEKS CASE – INOTROPES AND VASOPRESSORS In treating a patient who presents with shock, there are a number of components to the treatment. These include recognition of shock, treating the precipitant (e.g. sepsis, bleeding), commencing supportive management such as oxygen, commencing monitoring of the patient, optimise pre-load through IV filling and considering inotropes/ vasopressors. This discussion focuses on the last point, that of inotropes and vasopressors: What are the pros and cons of each agent? What should we use for certain clinical conditions? Inotropes increase the force and velocity of myocardial contraction with increased contraction, stroke volume and cardiac output. Vasopressors increase vascular tone with raised MAP (Mean arterial pressure) and systemic vascular resistance (SVR). These agents act predominantly through alpha 1, Beta 1, Beta 2, and dopaminergic receptors, the density and proportion of which modulate the physiological responses of inotropes and pressors in individual tissues. As a reminder: A1; vasoconstriction, increase in SVR A2; smooth muscle contraction, inhibition of transmitter release, platelet aggregation (i.e. clinically not relevant in this scenario) B1; positive chronotropes, increase heart rate; positive inotrope, increase in contractility B2; vasodilatation D1 and D2 dopaminergic- renal and mesenteric vasodilatation Note that specific cardiovascular responses are further modified and number of factors including: Reflex autonomic changes affecting heart rate, SVR, and other hemodynamic parameters. Receptors can be desensitized and downregulated. Binding affinities of individual inotropes and vasopressors to receptors can be changed with metabolic conditions such as hypoxia or acidosis Ability of the organ to respond to receptor stimulation The table below summarises the specific organ effects of each drug. Note the American terminology (epinephrine = adrenaline / norepinephrine = noradrenaline, isoproterenol = isoprenaline) and the fact in the ED in NSW we do not use or have access to levosimenden, amrinone, and milrinone. Some comments on the drugs that we use. Noradrenaline Potent Alpha 1 receptor agonist with modest Beta 1 activity Potent vasoconstrictor with less potent direct inotropic properties. Subsequently increases systolic, diastolic (with increased coronary blood flow, also via release of local cardiac vasodilators), and pulse pressure and has a minimal net impact on CO. Minimal chronotropic effects- may have reflex bradycardia with rise in MAP (mean arterial pressure). Rise in resistance yet thought to have little impact of splanchnic blood flow in septic shock Editor: Peter Wyllie Adrenaline High affinity for Beta 1 & 2-receptors present in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle (esp at low doses) with alpha-1 effects at higher doses. Increase in MAP counterbalance by skeletal mm v/d. Coronary blood flow is increased via local v/d release and prolonged diastole yet may also have alpha-1 coronary vasoconstriction. May reduce peripheral, renal, gut perfusion. Metabolic effects with hyperglycaemia and lactic acidosis. Dobutamine Strong affinity for both Beta 1 & Beta 2 receptors, which it binds to at a 3:1 Potent inotrope, with weaker chronotropic activity. Alpha 1 and B2 stimulation balances out with the net vascular effect is often mild vasodilation, particularly at lower doses (<=5 µg/kg/min). Doses up to 15 µg/kg/min increase cardiac contractility without greatly affecting peripheral resistance and vasoconstriction progressively dominates at higher infusion rates. With increased heart rate there is a increase in myocardial oxygen consumption. Isoprenaline Non-selective beta agonist with very low affinity for alpha receptors Chronotropic and inotropic properties, with potent systemic and mild pulmonary vasodilatory effects Increase in stroke volume with drop in SVR with neutral or negative effects on MAP – fall in diastolic BP. Phenylephrine Alpha activity and virtually no affinity Beta receptors- no direct effect on HR (may have reflex bradycardia). Can be given as bolus for severe hypotension, including in setting of AS or HOCM or to correct hypotension with concomitant ingestion of nitrate or sildenafil. Dopamine – A favourite in the past due to alleged renal sparing effects, and still used in the US , yet drifted out of favour in Australian practice. Dopaminergic then beta then alpha effects with increasing doses. Ephedrine Acts directly on beta 1 and beta 2 receptors, and indirectly on alpha1 receptors by causing noradrenaline release Rise in blood pressure and heart rate, and some bronchodilation. Lasts 5-15 min What about metaraminol (Aramine)? This works through potent and selective alpha stimulation + stimulation of noradrenaline release from the sympathetic nerve endings – Duration ~ 20 min – Can result in reflex bradycardia, and increased afterload that may be harmful with cardiogenic shock or decompensated mitral regurg. However lack of inotropic effect makes it useful in management of hypotension with AS or HOCM. Editor: Peter Wyllie CLINICAL SCENARIOS Cardiogenic Shock Complicating AMI- aim for reperfusion therapy ASAP (thrombolysis or angio) – use drugs as a bridge but the problem is that the inotropes may increase myocardial oxygen demands with increased ischaemia & arrhythmias. The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association suggests: Dobutamine if SBP 70-100 mm Hg in the absence of signs and symptoms of shock. If the patient is shocked with BP 70-100 they suggest dopamine yet definitive evidence supporting the use of specific agents in this setting is lacking. As mentioned dopamine is less commonly found in EDs so an alternative may be adrenaline yet there is a thought that this may exacerbate lactic acidosis and promote thrombosis in coronary vasculature. An alternative strategy may be to combine dobutamine with lower dose adrenaline or noradrenaline- depends on how much time you have and what is available now for your patient. If SBP < 70mmHg they suggest noradrenaline. ? Role of vasopressin if no response to noradrenaline. CCF – The main problem with decompensated heart failure is that there is often elevated SVR with reduced peripheral perfusion. Thus there may be a role for vasodilators such as SNP or GTN and inotropes with peripheral v/d properties. However studies have shown a consistent increase in mortality from +ve inotropes in chronic heart failure, and as a result the ACC/AHA don’t recommend routine use in chronic heart failure yet it may be considered for palliative symptom control. The European Society of cardiology acute HF guidelines suggest for those with hypotension and peripheral hypo-perfusion, dobutamine (class 2 a) or dopamine (2b-see point above). Sepsis – Noradrenaline (adrenaline – added to or substituting for noradrenaline) Cardiopulmonary arrest – adrenaline; vasopressin is controversial & more expensive –note that as per the AHA resuscitation guidelines from 2010 “there is no placebo-controlled study that shows that the routine use of any vasopressor during human cardiac arrest increases survival to hospital discharge”- this includes adrenaline. Bradyarrhythmias- (also for overdrive pacing of Torsade) -consider agents with B1 chronotropic effects such as dobutamine or isoprenaline as a bridge to reversing the precipitant, or applying temporary / permanent pacemaker. Reference: Inotropes and Vasopressors: Review of Physiology and Clinical Use in Cardiovascular Disease, Circulation Issue: Volume 118(10), 2 September 2008, pp 1047-1056 / Senz A, Inotropes and vasopressor use in the emergency Dept. EMA 2009; 21: 342-51/ Surviving sepsis Guidelines RHINOSINUSITIS The US Infectious Diseases Society of America published its recommendations for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) infections in 2012. A few points in summary: -It’s common -Viral much more common than bacterial (~ 2-10% of cases)- thus a concern regarding overuse of antibiotics Editor: Peter Wyllie - Due to the lack of precision and practicality of current diagnostic methods, clinicians must rely on clinical presentations to distinguish bacterial from viral rhinosinusitis. They suggest that the infection is probably bacterial if any of the following are true: Onset with persistent symptoms or signs compatible with acute rhinosinusitis lasting for ≥ 10 days without any evidence of clinical improvement; Onset with severe symptoms or signs of high fever (≥ 39°C) and purulent nasal discharge or facial pain lasting for at least 3-4 consecutive days at the beginning of an illness; or Onset with worsening symptoms or signs characterized by new onset of fever, headache, or increase in nasal discharge following a typical viral upper respiratory infection that lasted 5-6 days and initially improved ("double-sickening"). Treatment; Augmentin –as higher rate of H.influenza since Strep pneumonia vaccinations has lead to reduced number of Strep pneumoniae sinusitis + B-lactamase resistance with H. Influenzae Note that Therapeutic guidelines still recommends amoxicillin with augmentin if symptoms don’t improve / (doxy as alternative in adults- cefaclor in kids) Length of Treatment- Adults: 5-7 days for uncomplicated ABRS / Children: 10-14 days Adjunct therapy: - Intranasal saline irrigations with physiologic or hypertonic saline may be helpful in adults but are less likely to be tolerated in children; - Intranasal corticosteroids are recommended in persons with a history of allergic rhinitis. - Topical and oral decongestants and antihistamines are not recommended. Refs: Chow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, et al. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2012; 54:1041-1045. TRIAL OF THE MONTH I was sent this article last week for some reason. Thank the Dutch for this one. Van Nood E et al. Duodenal Infusion of Donor Faeces for Recurrent Clostridium difficile in the NEJM in January 2013- patients were given 1-2 faecal transplants as an infusion through a nasojejunal tube with the aim of eliminating C.diff. Something for Anna to discuss at journal club but it raises a number of issues that concern me. How did they double blind the study? Can anyone be a poo donor or do you need to be matched? Is prior diet an issue? The samples were “immediately transported” to hospital – police escort? How did they chart the dose - POO 1 pan NG? Can you give it as a push? Did they look for halitosis or a “nutty” after-taste as an adverse event? Did they look at staff satisfaction- or did everyone go home having a shit day? The paper raises more questions than answers! Editor: Peter Wyllie