USCG SIRMP Faclitators Handbook

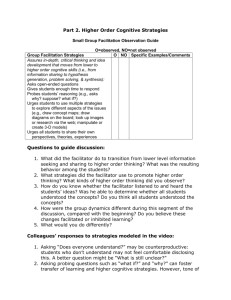

advertisement