World War I and the Federal Presence in New Mexico

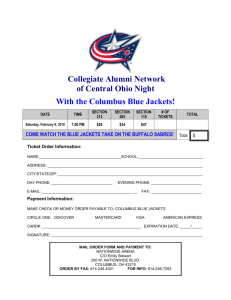

advertisement

World War I and the Federal Presence in New Mexico Black Soldiers at Camp Furlong The front-page article in the Albuquerque Morning Journal for Sunday August 26, 1917 reported “Colored Troops Not Disorderly at Deming Camp.” Military officials and the Deming sheriff “denied published reports that an impending clash between civilians of Deming and members of the Second battalion of the Twenty-fourth United States Infantry (colored) stationed here [Deming] had caused the removal of the troops.” The same officials said the Twenty-fourth’s relocation to their home base at Camp Furlong in Columbus “had been expected for a week.” Not mentioned in the article, but known to everyone, was the riot earlier in the week by another battalion of the Twenty-fourth Infantry. On Thursday evening August 23, 150 of the 654 black enlisted men in the Twenty-fourth’s Third Battalion mutinied at Houston’s Camp Logan. After commandeering rifles and ammunition, they marched in formation for three hours along the streets of west Houston, where they shot and killed twenty civilians. Forty-eight hours later two trains pulled out of Houston carrying the Third Battalion back to its base in Columbus, New Mexico. The “Houston Riot of 1917” is a stark reminder of smoldering hatred. White Texans (and many others throughout the South) embraced “Jim Crow” segregation laws to enforce demeaning and discriminatory practices such as separate seating sections for blacks. Black challenges to racist practices resulted in violence. When a black soldier of the Third Battalion, unused to Houston’s Jim Crow practices, ignored a streetcar’s “colored section,” a beating by police ensued. Other police assaults on soldiers coalesced into a call for reprisals, which led to a spontaneous black mutiny. The troops of the Third Battalion had recently returned from the Philippines, where acceptance by locals meant their four-year tour “constituted one of their most pleasant assignments.” Six months after returning to the United States, and immediately following PanchoVilla’s raid on Columbus, the Twenty-fourth received orders to reinforce Camp Furlong. The troops guarded the 150 mile supply line linking General Pershing’s headquarters in Mexico to the border. The unit’s three battalions remained at Camp Furlong after all troops exited Mexico in early February 1917. In late July came new orders: guard duty at camps being built for recruits to the new National Army. The First Battalion departed for Camp MacArthur in Waco, Texas, while the Second and Third, respectively, went to Camp Cody in Deming and Camp Logan in Houston. At three courts martial between November 1917 and March 1918 a total of sixtythree soldiers of the Twenty-fourth Battalion faced military justice. The first convictions, on mutiny and murder, led to hanging thirteen soldiers just outside Houston on December 11, 1917. Forty-one sentenced to life in prison served terms of varying length, with most released by the early 1930s and the last soldier left Ft. Leavenworth in1938. The reminder of the Twenty-fourth’s troops spent the war years at Camp Furlong, and beginning in April 1920 and throughout the next several years the Twenty-four were the only U.S. Army troops stationed in Columbus, New Mexico. Race relations in southern New Mexico were markedly better than in Houston, but it took awhile for rumors and emotions to quiet down. At the end of August, newspapers in Texas fanned the flames of racism by predicting violence in Columbus. A Houston paper claimed a soldier on the departing train tossed a slip of paper stuffed into an empty cartridge shell. Military officials deemed it “of a threatening nature.” It read: “We done our part in Houston and are on our way to Columbus, New Mexico.” More ominous threats were intercepted by agents of the Army’s military intelligence. They reported “men of the 24th Infantry . . . had said that if the Houston Mutineers were convicted by court martial, they would wreck nearly Columbus, seize machine guns, and join Pancho Villa in Mexico.” In fact, though, nothing came of the boasts, and calm settled across the town and its army post. What happened in Columbus, New Mexico in the years immediately after the Houston Riot is little known; however, it is an important part of the history of race relations in America. Jim Crow laws did not exist in Columbus, but their legal sanction remained in place across the country. For the first half of the twentieth century, communities such as Columbus and federal entities such as the Army worked out how blacks and non-blacks encountered each other. In examining local experiences such as the Twenty-fourth’s in Columbus, we glimpse a pivotal evolution in race relations—the journey toward equality. The legality of “separatebut-equal” facilities affirmed by the Supreme Court in its ruling Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) occasioned a strong dissent from Justice John Marshall Harlan. He said segregation violated equality under the law as provided for in the thirteenth and fourteenth amendments to the Constitution. He famously asserted that, “Our constitution is color blind and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” But nearly sixty years would pass before the Supreme Court validated Justice Harlan’s views, and in the intervening decades many different gradations existed within racial segregation. One such ‘refinement’ emerged in Columbus, New Mexico. Social scientists know that border regions can be fluid, serving as bicultural links between different social groups. Was Columbus such a town from 1917 into the early 1920s? The available data do not permit more than a rough sketch of its population, but incidents and experiences do suggest it was a bicultural community. Columbus tripled in size to about 2,500 residents between 1916 and 1920. But Camp Furlong always had more occupants than the town: 1,419 soldiers (1,170 black) in 1917 and 4,109 (3,599 black) in 1920. The town’s racial composition included a tiny black civilian population with Hispanics likely outnumbering Anglos, though they did not equal the latter’s economic influence. For example, the town’s mayor was an Anglo as were many of its businessmen. Camp Furlong, as one scholar noted, “At its height . . . represented one of the single largest black military communities ever to reside in the West.” The Army camp south of town dominated the town’s economy and influenced every aspect of its life. Moreover, a series of biracial events, most of a social nature, suggests a muted segregation existed in Columbus. In the first half of the twentieth century, black ministers increasingly emerged as effective and respected spokespersons for their communities. The same role is seen in the activity of the black pastor at Camp Furlong, Chaplain Alexander W. Thomas (African Methodist Episcopal Church). While providing spiritual guidance for the Twenty-fourth, his greatest contribution came in linking town and camp. He collaborated with community leaders and white officers to ensure the Twenty-fourth actively supported projects as diverse as Red Cross fundraising, War Bond sales, and national holiday celebrations. Frequently everyone participated freely in such activities. As one scholar found, Typically, holiday celebrations and special events included civilian and military, black and white, members of the town. These celebrations usually featured a full schedule of sporting activities, parades, and picnics. . . . The holiday celebration for July 4, 1919, was planned by a biracial committee composed of civilians, military personnel [including Chaplain Thomas], and representatives of several welfare groups. The Twenty-fourth’s highly regarded band always proved a popular draw at these and many other events. Segregation overlay race relations in Columbus. Both on and off base, separation of blacks and whites went unchallenged. A measure of just how invisible blacks were to whites is evident in the camp’s weekly newspaper, 12th Cavalry Standard. From its first issue on February 23, 1918 to its fiftieth issue a year later, the Twenty-fourth is rarely mentioned, despite extensive coverage given to social activities and community events. For many months, no mention of the Twenty-found is found in the paper’s six to ten pages. Only in May 1918 did the Twenty-fourth merit two short notices—once concerning religious services (4th) and when the camp bands’ schedule appeared (18th). But something else was going on at Camp Furlong and in Columbus that worked to subvert the prevailing racism. Racial harmony slowly, tentatively appeared when blacks and whites worked and relaxed together. Consider the summer of 1919: Blacks in Columbus celebrated emancipation on Juneteenth (June 19th), and on Independence Day blacks and whites united in festivities. That same summer, in twenty-five cities across America race riots and bloodshed occurred. This spasm of civil unrest, known as the “Red Summer of 1919” for its bloodiness, had its prelude in the Houston Riot of 1917. But in Columbus all was quiet—a calm borne of reconciliation and not fear. A final measure of just how much harmony had returned to the Twenty-fourth is seen in a sample of re-enlistments in 1920. For the first two and final two months of the year, 48 blacks and 1 white reenlisted at Camp Furlong, with most of the blacks drawing new duty in Panama or in the Philippines. The federal presence in Columbus reveals a history of race relations in sharp contrast to what prevailed in the segregated, Jim Crow-dominated South. It was still a history of segregation, of course, since the Twenty-fourth was and remained for decades after black enlistees led by white officers. But collaboration and intermingling existed to a large degree, and in these incursions in each other’s experiences blacks and non-blacks slowly began to negotiate mutual acceptance, a first step toward equality. © 2008 by David V. Holtby Bird’s Eye View of Columbus, NM, 1916. 000-742-0160, William A. Keleher Collection, Center for Southwest Research, University Libraries, The University of New Mexico. Albuquerque Morning Journal. August 26, 1917.