Wildlife Tourism and Poverty: Present State and Strategy for

advertisement

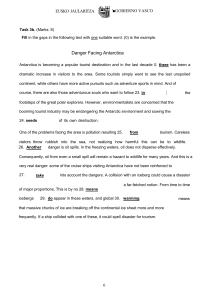

Wildlife Tourism and Poverty: Present State and Strategy for Development in South Sudan. “We will spare no effort to free our fellow men, women and children from the abject and dehumanizing conditions of extreme poverty to which more than a billion of them are currently subjected” (UN). Bojoi Moses Tomor Head, Department of Wildlife Science, College of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies, University of Juba. E-mail: btomor@hotmail.com Introduction Sudan is the largest country in Africa covering an area of 2.5 million km 2. Due to this large size, the country is covered by many climatic and ecological zones. This diversity in habitats is in turn reflected in the country’s diverse wildlife comprising all 12 orders of mainland African mammals (224 species and subspecies, 7 of which are endemic), 938 bird species and 136 reptile species. By any standards, Sudan is an exceptionally beautiful and interesting country. The country has extensive protected areas covering an area of 4.8% of the total land surface and hosts a variety of ecosystems, cultures and wildlife that are major attractions for nature oriented tourists. Sudan’s wildlife resources are considered among the finest in the world and therefore are an international level resource of great economic potential. Most of Sudan’s wildlife occur in South Sudan where 16 of the country’s 26 protected areas are found and the diversity of wildlife more apparent. In the Sudd swamps alone, there are 100 species of mammals and over 470 species of birds. In recognizing this diversity and potential, the Directorate of Tourism in the Federal Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife in its tourism development program designated South Sudan within the Southern Circuit, which is to be developed for tourists with interest in wildlife viewing, photo safaris and hunting. Unfortunately, the Directorate has not developed any plan of action for the circuit. To date it is not clear whether wildlife country wide is a resource or a liability under the current wildlife management system. Sudan has a relatively huge economic potential in terms of its endowment of natural resources, people and a diversified and pervasive climatic zones. Despite all this however, the country faced serious economic difficulties over the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s which led to the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) registering a negative growth rate of 2%. This trend has since the advent of oil production in 0 the late 1990s reversed to positive territory of 6% per annum. In 2003, GDP rose to 5.9% (US$ 15.4billion up from US$12 billion in 2001). By far the largest contributor to GDP is agriculture (39%), while the tourism sector contributes just 0.3% to GDP. Unfortunately, this impressive GDP growth rate and signs of economic recovery have done little to reverse the upward trend in poverty. The available poverty indices suggest that poverty remains one of the most serious problems in the Sudan. More than 90% of the population in the country is classified as poor both in the rural and urban areas. Of the poor, 70 % live in rural areas where the resources that contribute to the positive economic out look are based. Additionally, human development indicators such as literacy rates, life expectancy and child mortality are far below the levels in many middle-income countries. This has led the country to be categorized as one of the Least Developed Countries (LDC) among developing countries (WTO, 2004). Under the present circumstance, the prospect of the Sudan meeting the MDG target of halving the number of its poor by 2015 is bleak despite the oil boom. As such imaginative approaches that take into consideration the contribution of all potential income generating and livelihood improvement sectors should be sought in order to score success and avoid the pitfall of dependency on a single resource. As wildlife is a component of many development schemes such as common pool resource management and community based natural resource management strategies, the primary objective of this paper is to generate a better understanding among policy makers in South Sudan about the role wildlife tourism can play in sustainable development and conservation. A brief look at the present state of tourism in the Sudan in order to highlight the opportunities and constraints inherent in the industry sets the basis for argument. A review of the role wildlife plays globally in improving livelihoods of the poor living with wildlife as a mechanism for identifying an environmentally friendly, socially acceptable and economically viable approach to wildlife utilization will form the second part of the paper. The third part of the paper explores the linkages between wildlife tourism and poverty. Current knowledge on the relationships between wildlife tourism and sustainable development are addressed in part four. Drawing on all the above, the paper then concludes by recommending broad action programs that the Ministry of Environment, Wildlife Conservation and Tourism (MEWCT) can undertake in order to develop a sustainable wildlife tourism plan for South Sudan. In the conclusion, emphasis is placed on the importance of sustainable wildlife tourism as an ideal mechanism for utilizing South Sudan’s wildlife and its contribution towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) of poverty reduction and environmental sustainability. 1 1 State of Tourism in the Sudan Tourism in the Sudan dates back to pre-independence days and history has it recorded that as early as the 19th century, foreign visitors and explorers had started coming to the Sudan mainly for big game and exploration. The first tourism office opened in 1939 which later developed into the tourism and hotels corporation in the 1970s. The first tourism legislation was enacted in 1977 and was called “Tourism and Hotels Corporation Act (1977)”. This Act has since then been repealed twice and is in the process of being repealed so that it complies with the CPA and the Interim National Constitution. Tourism development is one of several economic development strategies available to a nation. It is the principle export of one third of all Developing Countries and the major foreign currency earner for 49 of the Least Developed Countries (WTO, 2004). In 1992, the World Tourism Organization (WTO) estimated global expenditure on tourism to be US$ 3,5 trillion, making it the largest industry in the world. In 2001, the industry generated US$142,306 million to developing countries (WTO, 2003). By 2004, the same body reported a total sum of US$ 622 billion in receipts from international travel alone. According to WTO (2004), the industry still is a major global economic activity that has grown by 25% over the last 10 years despite threats from global and regional crisis like the 9 / 11 terrorism attack in New York, the SARS outbreak in south east Asia and the Asian tsunami. The strongest growth of the tourism industry has been recorded in the developing world with sub-Saharan Africa showing a strong growth rate of 5.5 % compared to a global average of 4% (WTO, 2004). In 2000, tourism in the Sudan contributed just 0.3% to GDP and in 2003, the industry generated US$ 56 million. Though Sudan’s share of the industry is minimal at the continental level, its growth rate of 6 % over the last 5 years is promising. The only problem is that 25% of the international tourists who visit the country come from the Middle East and most of them are here either on a business trip or on a mission. Traditionally, most of Sudan’s nature and wildlife based tourists come from Europe. In Dinder National Park, Tomor (2006) found that 73% of the annual average 300 foreign ecotourists to the park were Europeans and only 16% were from Asia (Mainly Middle East). 1.1 Attractions The strength of the appeal of a destination to tourists is linked to the quality of attractions it can offer. It is the attractions at a destination that stimulate an interest in visiting a country. Attractions provide the visitor with the essential motivation to choose a destination and latter assess satisfaction. It is also the attractions that provide the elements used to develop an image of the destination to attract potential tourists. 2 Sudan is a country for the adventurous tourist who is keen in exploring new frontiers in the areas of wildlife viewing and photography, discovering cultures, scuba diving, desert trekking and antiquities. These forms of tourism have not been fully developed as they lack the support structures to make the product complete for sale in the international market. 1.1.2 Wildlife There are 26 protected areas (National Parks – 9 and Game Reserves – 17) in the Sudan in which wildlife tourism can be practiced. The most frequented, oldest and accessible during the 22 years of civil strife is the Dinder National Park which hosts an average 300 foreign tourists annually. The park however, like all other protected areas in the country has never had or used a management plan (Nimir et al, 2003). Most of Sudan’s 26 protected areas are found in South Sudan covering about 2% of the region. The most notable of these protected areas are Nimule (elephant), Southern (white rhino), Boma (white eared kob), Badingilo (black rhino) and Kidepo. There are no recent data on the status of wildlife in these protected areas because of the just ended war. The only information available comes from earlier censuses conducted in the 1970s and early 1980s (Table 2). The wildlife in South Sudan is also well known for aggregating in large numbers of mixed or single species herds or flocks. No where is this aggregation more apparent than it is in the Boma plains where in the 1980s, Watson (1977), reported sighting over 1 million white eared kob (Kobus kob leucotis). In the plain, mixed herds of White eared kob, Mongalla gazelle (Gazella t. albanotota), tiang (Damalicus korrigum) and zebra (Equus burchelli) form especially during the dry season. It is also in South Sudan that all the “Big Five” (Lion Panthera leo), Leopard (Panthera pardus), Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), Elephant (Loxodanta africana) and Rhino (Ceratotherium semum and Diceros bicornis)) can be found in a single protected area. 1.1.3 Archeology Sudan’s archeological areas stretch from Khartoum to Wad Halfa along both banks of the Nile. The closest to Khartoum in the Shendi area are the monuments of Bigrawia, El Mosawarat es Sufra, Naga’a and Wad Ban Naga. Beyond Shendi are Karma, Nuri and Jebel al Barkal. Some of the monuments which were flooded after the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1964 were relocated to Khartoum and reconstructed in the Natural History Museum where they are currently housed. The paintings collected at the sites are also displayed in the gallery of the museum. 1.1.4 Desert Deserts represent complex tourism attractions, showcasing natural, geological, and archeological features as well as nomadic cultures and traditions. Much of Northern Sudan is desert and ideal for tourists interested in desert trekking. 3 Desert trekking is not well established in the Sudan except for hunting safaris in search of Nubian Ibex (Copra ibex nubiana), Dorcas Gazelle (Gazella dorcas), Oryx (Oryx dammah), Barbary Sheep (Ammotragus lervia) and Bustard. 1.1.5 Red Sea Sudan’s coastline contains some 640 km of well ventilated (46 m depth) water of uniform temperature (23 – 30 C up to a depth of 150 m) teaming with unspoiled coral reefs and other marine animals. It is an ideal site for tourists interested in snorkeling, Scuba diving and underwater photography. It is currently the biggest attraction for tourists to Sudan. In recognizing its significance, the government designated 260 km2 of the coastline at Sanganeb as a Marine National Park in 1990. 1.1.6 Mountains Mountain ranges such as the Imatong mts. in Eastern Equatoria and the Jebel Mara mts. in Darfur display unique cultural richness, economic fragility, decline in traditional populations and activities and sensitive biodiversity. These form important ingredients for specialized tourists such as hikers and explorers. Unfortunately, tourism in mountainous sites has never been tried in the country and the location of the two sites puts them at a disadvantage in terms of priority. 1.2 Constraints to Tourism Though fundamentally important, a viable tourism industry requires more than a range of attractions and a welcoming people. Sound infrastructures along with a developed superstructure of facilities and amenities as well as an enabling environment are also needed. Tourism is a highly diverse industry that requires many different components for it to be a complete product that can be sold in the market to potential buyers. Therefore, a deficiency in any one component can undermine the suitability of a destination for tourism. The Sudan has been lagging behind in the tourism business simply because it places its faith in the natural beauty of the country while forgetting the fact that no profit can be generated from the beauty without proper investment for its development. 1.2.1 Infrastructure International access to Sudan is relatively difficult and expensive because up to 2005, there was only one direct flight by Lufthansa from the European market to the country. Other carriers like British Airways get to Khartoum from Heathrow by way of Oman. There are other indirect flights to Khartoum by way of Egypt, Syria, Ethiopia and Yemen but these indirect routes increase travel time and cost. The situation of the national carrier, Sudan Airways has been so bad that 80% of its domestic routes have been taken over by private airlines. Marsland Aviation controls 70% and Airwest and Mid Airline control the remaining 10% leaving the national carrier with just 20% of the domestic routes. There is also a limited fleet of charter airlines in the country such as Blue Bird and Helilift. 4 Although Sudan has 63 airports, 12 have paved runways and only three are of international standard (Khartoum, Port Sudan and Juba). At present, just 6 airports have night landing facilities and two; Khartoum and Port Sudan are equipped with the Instrument Landing System. Sudan’s road systems of mainly dirt trucks (88%) cover a total 32,000 km. Of these, 3,600 km are paved and another 4,000 km graded to all weather standard. All asphalt paved roads are concentrated in central Sudan (Khartoum State) with outlets to the northern, eastern and western states. In all 10 states of South Sudan, there are no asphalt paved roads. All graded roads in the south were either rundown or mined during the 21 year war. Following the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and formation of the Government of Southern Sudan (GOSS), the Ministry of Roads and Transport has managed to grade 882 km of road with a further 1200 km under construction. Much progress has been made in the telecommunication network but the progress is skewed towards the center. By 2002, there were over 650,000 fixed lines, 190,000 mobile subscribers and 84,000 internet users. In the last 3 years these figures have grown to the extent that Mobitel, the first mobile service provider in the country has more than 1.5 million subscribers and Sudani, the latest addition has over 500, 000 subscribers. Unfortunately, this progress like all others is limited to central Sudan and some northern states. South Sudan remains as distant as it was before the CPA. 1.2.2 Accommodation For a viable tourism industry, some form of comfort should be provided to visitors. Comfort in the form of accommodation could be a hotel, motel, inn, lodge or tented camp. In the Sudan, quality accommodation is concentrated in Khartoum where 90% of the categorized hotels and inns are found. Over the last 23 years, the number of categorized accommodation has grown from 16 in 1983 to 64 in 2005. All the 4 and 5 star hotels are found in Khartoum with the exception of the Port Sudan Hilton. The only categorized accommodation in South Sudan is the run down Juba Hotel (28 rooms) and Equatoria Hotel (>20 rooms) which are considered 1 star hotels. Following the signing of the CPA, a new form of accommodation has emerged in Juba. A number of tented accommodation in the likes of Afex, Juba Raha, Bros, and Nile Comfort Inn carter for the many visitors to Juba. A common feature of the accommodation facilities in the Sudan is that all are concentrated in urban centers away from sites of tourist attractions. Additionally, 91% of the accommodation facilities have capacities of less than 100 beds. 5 1.2.3 Personal security and safety More than any other factor, threats to personal security and safety adversely affect tourism demand. The fear of terrorism can affect global travel trends. When regional wars, rebellions and terrorism occur, domestic and international travel falls, and fewer tourists visit destination areas. The effects are felt most in developing countries, where international visitors are often a significant proportion of all visitors. A sense of personal security is also affected by the prevalence of violent crime, petty theft, water quality, disease or bad sanitation. The Sudan for many years has never been a favorable destination for tourist. After the imposition of Islamic Sharia Law in 1983 which sparked the civil strife in South Sudan, the number of tourists to the country fluctuated between 30 and 40 thousand throughout the 1980s. In the 1990-1991 periods, the number declined by 50% from 33 thousand to 16 thousand following the out break of the Gulf War and Sudan’s support for Iraq. In the 2000s, the 9 /11 terrorist attack in New York did not dampen growth in the industry in the Sudan as the WTO reported a growth of 18% between 2000 -2002 (WTO, 2003). This was expected because Americans form an insignificant market for Sudan’s tourism. In the Sudan, the climate for tourism development improved following the signing of the Machakos Protocal and subsequently, the CPA. In South Sudan, throughout the last 22 years, few tourists ever tried to venture into the region for pleasure due to two main reasons. First, the attractions of South Sudan, the wildlife in the protected areas were either driven away, poached or could not be accessible from the urban centers because most roads were mined. Second, the widespread possession of fire arms by civilians and the many militias formed in the region meant that personal safety could not be guaranteed. 1.2.4 Services Tourists are increasingly demanding high quality recreational opportunities and the services that support them. Those who receive quality service during their normal working week expect to be offered this by their leisure providers as well. They expect guides to be knowledgeable and good communicators. They want their hosts to make them feel welcome, comfortable and part of the communities they visit. Sudanese are well known world over as warm, open and friendly people with a long tradition of generous hospitality. However, the services they provide in accommodation establishments, restaurants, protected areas and tourism agencies are not professional. In most cases, the tourist agencies do not have service quality goals, or monitoring programs, making their programs appear unresponsive and primitive. This is because most of the people working in these establishments had no formal education in the services sectors in which they serve. 6 1.2.5 Training Training is about developing the potential and ability of stakeholders to make and implement decisions that will lead to more sustainable tourism, by increasing their understanding, knowledge, confidence and skills. In the Sudan a large proportion of the workforce in the tourism sector got no formal tourism training whether in government Ministries, accommodation establishments, tour operators or at the community level. For example, in the Directorate of Tourism in the Federal Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife, only 9 out of the 63 staff of the Directorate had some formal tourism training. In the states, the situation is even worse with only 4 unskilled staff manning the tourism unit in each State Ministry of Culture and Social Affairs. At the South Sudan level, a Directorate of Tourism has been established in the Ministry of Environment, Wildlife Conservation and Tourism but it is still under structuring and has yet to draw up its programs and policies. 1.2.6 Tourism Institutions Since the establishment of tourism in the Sudan, its administration has shifted several times. As a result of the shifts the directorate underwent, no proper policies have been developed for the operation of the industry and the links between the Directorate and state tourism units have not been clear. Today, responsibility for the development of tourism rests with the Directorate of Tourism in the Federal Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife. In the states, the development of tourism is a responsibility of the tourism unit in the Ministry of Information, Culture, Youth and Sports. States in some parts of the Sudan are legally allowed to develop their own tourism policies and programs guided by the legislation and the standards set by the Directorate of tourism. For South Sudan under the CPA and the Interim National Constitution, the Directorate of Tourism of the MEWCT oversees the development of tourism programs in the region. It has the legal right to develop its own tourism program independent from the program for the Directorate of Tourism in the Federal Ministry of Tourism and Wildlife. The responsibility of state tourism units is to enforce tourism regulations and create a good atmosphere for tourism. At all levels of government, the tourism industry in the Sudan lacks support institutions such as tourism boards, training institutions, associations, societies or councils. 1.2.7 Legal framework Legislation, regulation and licensing are inter-related tools that can be used to strengthen tourism management by setting out requirements that are 7 compulsory and enforceable, and which lead to sanctions and penalties if they are not met. Legislation provides the authority to enforce requirements, which are defined and elaborated by regulations. Licensing is a process of checking and signaling compliance with regulations or otherwise identified obligatory standards, conveying permission to operate. In its present state, tourism country wide is governed by the 1995 Federal Tourism and Hotels Act derived from the 1977 tourism and Hotels Corporation Act. In accordance with the provisions of the CPA and the Interim National Constitution (2005), South Sudan has to develop its own tourism laws upon which the government sets the regulations based on national and international standards. The relevant ministries in the 10 states then enforce the regulations. Many pieces of legislation that have impact on tourism are not specifically enacted for the benefit of tourism alone. They include laws in areas such as taxation, customs and immigration, transport, public safety, health, environment and planning. Although legislation in these areas is responsibility of the relevant ministries, it is important that the Ministry of Environment, Wildlife Conservation and Tourism (MEWCT), has a consultative input. 1.2.8 Research The importance of research as a planning and management tool appears not to have been realized by tourism policy makers in the Sudan. This may explain why there are no publications on the subject since the inception of the industry. The only attempt at assessing the state of the industry in a protected area is Tomor (2006), whose study covered ecotourism in Dinder National Park during the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Tourism policy makers appear not to have realized that research provides new knowledge, insight and procedures for tourism management. They seem not to be aware of the fact that ongoing research programs can reveal trends and patterns that are valuable for planning and management. 2 Linkages between wildlife and Poverty The millennium declaration of the UN identified poverty alleviation as one of the most compelling challenges the world is facing in the 21st century. Tourism is one of the most important sources of foreign exchange earnings and job creator in many poor and developing countries. The WTO believes that tourism can be used to address the problems of poverty more directly. Wildlife plays a key role in linking the poor with tourists. About 80% of all international travelers to Africa are attracted by its wildlife. It plays a significant role in the livelihood of poor people living in rural areas. It is a coping mechanism for the poor during periods of stress and the lack of it creates vulnerability to hunger. 8 2.1 Wildlife and poverty The extent to which people depend on wildlife for their survival comes in different shades and colors. Here a few of these linkages are addressed with the aim of selecting a more sustainable linkage to be adapted for the development of the wildlife sector in South Sudan. 2.1 Wildlife and hunger In many African countries, bush meat forms a significant source of animal protein. In Ghana, where all wildlife species are edible, 75% of the population eat bush meat regularly. Asibey and Child (1990) reported bush meat consumption rates of 84% in Nigeria, 70% in Liberia and 60% in Botswana. In the Sudan about 70% of the population lives in rural areas where access to other sources of animal protein is limited. It is therefore safe to say that about 80% of all Sudanese depend on wildlife for their animal protein needs. On the negative end, wildlife sometimes creates hunger when it interferes with human activities. It is estimated that about 35% of all agricultural production costs can be attributed to wildlife damage. Wildlife can also be a threat to human life and the livestock industry. 2.2 Wildlife and food security Wildlife has always played a significant role in the livelihood of the poor as a coping strategy during periods of stress. An assessment carried out by Save the Children Fund on the contribution of wild food to nutrition in South Sudan found that most of the population relied heavily on wildlife for their livelihood whether in the government held towns or in the New Sudan throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Loss of resources due to unsustainable methods of use and limited access caused by insecurity creates much dependency on wildlife for survival. In times of scarcity, wild things even as small as caterpillars and termites, can be key food sources. In Juba, rats in the vicinity of homesteads were exterminated by rat eating communities in the 1980s and 1990s due to high demand and limited options. This led to the expansion of the hunting rage for the rodents to the outskirts of town where some hunters unfortunately lost their lives. 2.3 Wildlife and income generation Income generated from wildlife comes primarily from consumptive and nonconsumptive wildlife tourism, wildlife hunting, trade in products and wildlife ranching and farming. According to a 1999 study by the World Conservation Society, each year more than 1.1 million tons of wildlife meat comes out of tropical Africa (WTO, 2003). 9 By all standards, tourism is the largest generator of income in the wildlife sector and the most sustainable utilization strategy. It is an industry that has had a very demonstrable impact in the economies of many countries in the world. Globally, the industry generated some US$ 443 billion in 1997, US$ 622 billion in 2004 and is expected to exceed US$ 2 trillion by 2020 (WTO, 2005). Tourism contributes 10.4% to global GDP and accounts for 12% of total exports in international trade. In countries like Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania and Botswana where much of the industry relies on wildlife, substantial revenue is generated from the industry. In 1998, about 12,344 million tourists visited sub-Saharan Africa. A majority of these international travelers went to South Africa (48%), Zimbabwe (13%), Kenya (8%), Botswana (6%), Tanzania (4%), Uganda (2%) and only 0.3% came to Sudan (WTO, 2003). In 2004, Kenya earned US$ 577 million, Uganda, US$ 512 million and Tanzania US$ 523 million from wildlife tourism (WTO, 2005) 3 Wildlife tourism and poverty Tourism is the world's largest industry, and every year it pumps billions of dollars into some of the poorest countries in the world. It creates jobs, reduces poverty, builds new roads, airports, hotels and hospitals. According to Louis D'Amore, president and founder of the Vermont-based International Institute for Peace Through Tourism, 46 of the 49 least-developed countries, have tourism as their largest foreign-exchange earner. It is the principle export for one third of all developing countries. The industry generated some US$ 142,306 million to developing countries in 2001. In 2004, Kenya, with one of Africa's mostdeveloped tourism industry, hosted about 600,000 tourists and pocketed US$577 million, or about 12% of GDP. On average, each tourist spent US$ 961 in the country. Tourism is growing much faster in developing countries than in developed countries. It is estimated that the industry is growing at a rate of 5.5% and 6% in Africa and Asia respectively, where a majority of the worlds poor live. This growth rates are considerably higher than the world average annual growth rate of 4%. 3.1 Wildlife tourism and poverty reduction Wildlife tourism has characteristics that fit perfectly with approaches for poverty reduction. Most poor people live in wildlife rich areas which are agriculturally marginal and/or remote from markets. In such areas where other livelihood diversification opportunities don’t exist, wildlife tourism does offer opportunities for enterprises and employment. It is in tourism that entry barriers to establishing new small businesses are quite low. Tourism also creates opportunities to support traditional activities such as agriculture and handicrafts. 10 In many countries including Sudan, wildlife along with much of the wildlife rich land (protected areas) is owned by the State. This means that governments can influence the pattern of private sector tourism development and its impact on poverty in the process of granting rights of use and access to these assets. These natural assets give many developing countries a comparative advantage over developed countries. Three quarters of people in extreme poverty live in rural areas much of which is attractive to tourism. Due to its location, wildlife tourism can provide seasonal employment opportunities to the poor in rural areas that can fit into their other livelihood opportunities. Being labor intensive, the industry creates opportunities for employment of women and young people. It is estimated that for every tourist, 8 jobs are created in the tourism sector, agriculture and other support business. Wildlife tourism supports conservation because the more poor people are the more demand they put on wildlife and the faster wildlife declines. Therefore in order to maintain wildlife productivity, it is important that poverty is reduced through wildlife tourism. Wildlife therefore can pay for its survival through a sustainable tourism program. 3.2 Approaches to poverty reduction through wildlife tourism 1. Employment of the poor in wildlife tourism enterprises Providing employment is one of the major ways in which wildlife tourism can contribute to the quality of life of poor people living with it. This enables poor people to benefit from the entrepreneurial skills and market access of those with established business. For better performance, increased staff retention, greater efficiency and productivity however, it is important that labor regulations are enforced and the principles of good employment practices (promotion, training, minimum age, safety and health) are observed. 2. Supply of goods and services to wildlife tourism enterprises by the poor Reduction of leakage of income generated from wildlife tourism from a destination area is vital if the industry is to improve the welfare of the poor. This can be done by encouraging and facilitating local sourcing of supplies. By encouraging tour operators to use locally based service providers and products, income generated from the industry can be retained for the benefit of local communities. 3. Direct sale of goods and services to visitors by the poor The informal sector is one of the most direct ways of getting visitor spending into the hands of the poor. Disadvantaged people often gain access to tourists and seek to earn income from them through activities such as street trading, sell of 11 handicrafts, pottering, personal guiding and informal accommodation. To avoid chaos and overcrowding, the informal sector can be strengthened through capacity building, quality control, licensing and providing tourists with better information. 4. Supporting the establishment of enterprises by the poor Supporting locally owned businesses or their establishment places power and control into the hands of the poor. This entails that poor people are encouraged to establish micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) through capacity building and financial support programs. Much of the profit generated by locally owned businesses is retained within the community. 5. Use proceeds from tax or levy on wildlife tourism income or profit in poverty reduction programs Income from wildlife tourism can be used to tackle social issues and benefit poor people indirectly. This can be done through development of pools of funding that can be directed towards social or community schemes such as education, health and social welfare. In Uganda 20% of wildlife tourism income is directed towards development of the local community involved. 6. Voluntary giving by wildlife tourism enterprises and tourists Payments into general charities and programs in destinations or specific support for projects by tourists or tour operators can be very effective in poverty reduction. 7. Investment in infrastructure stimulated by wildlife tourism Investment in wildlife tourism in a destination area can result in the provision of additional services such as roads, clean water, electricity, health care and telecommunication to rural communities living with wildlife. This can be of great benefit to poor communities in areas where it is difficult to reach people through traditional development activities. 4 Sustainable Tourism Over the last 30 years global awareness of sustainability issues has grown considerably. Most governments and development organizations agree that, without sustainability, there can not be development that generates benefits to all stakeholders, solves serious and urgent problems such as poverty and preserves the natural and built environment on which human prosperity is based. The analysis of the relationship between wildlife and poverty shows that wildlife tourism is the most sustainable approach for its utilizing. 12 4.1 Relationship development between wildlife tourism and sustainable Wildlife tourism is in a special position in the contribution it can make to sustainable development and the challenges it presents. Globally, it is the fastest growing sector of the tourism industry and commands about 80% of all international travel to Africa (Weinberg et al., 2002; WTO, 2004). Its dynamism, growth and contribution to the economies of many countries and local destinations puts it at a special position as a vehicle for sustainable development. The special relationship existing between consumers, industry, environment and local communities creates awareness about environmental issues and differences among nations and cultures. This relationship leads to dependency of visitors, who seek to experience intact and clean environments and exotic wildlife, on host communities whose hospitality is paramount for visitor spending. This direct and close relationship can be very positive for sustainable development. 4.2 International recognition of sustainable tourism The importance of tourism as a vehicle for sustainable development and the need for tourism to integrate sustainability principles has been increasingly recognized in international fora and echoed in policy statements. The UN Commission for Sustainable Development in its 7th session in 1999, urged governments to advance the development of sustainable tourism. Accordingly, governments were expected to develop policies, strategies and master plans for sustainable tourism based on Agenda 21, as a way of providing focus and direction for relevant organizations, the private sector and local communities. In 2001, the UN general Assembly endorsed the 1999 WTO Global Code of Ethics for Tourism that invited governments and stakeholders in the tourism sector to introduce laws, regulations and professional practices contained in the code into their tourism development plans. The Quebec Declaration on Ecotourism in 2002 (International year of Ecotourism) recommended to governments, the tourism industry and other stakeholders measures required to foster development of ecotourism on sustainable basis. The World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg (2002) called for promotion of sustainable tourism as a strategy for protecting and managing the natural resource base. The Convention on Biological Diversity Guidelines on Biodiversity and Tourism Development (2003) requires governments to integrate sustainable tourism into 13 their strategies and plans for tourism development and national biodiversity strategies and action plans. 4.3 Linkage between wildlife tourism and sustainable development The objectives of wildlife tourism and its benefits are more less similar to those of sustainable development. Wildlife tourism aims at generating financial support for formation, management and protection of natural areas, raising economic benefits for local communities living near protected areas and creating support by local communities for conservation. Wildlife tourism increases jobs and income for local communities living with wildlife. It is a source of foreign exchange given that it attracts mainly international tourists. Many governments of wildlife rich nations use the industry for economic development as it is comparatively inexpensive to create a job in the tourism sector than in other sectors of the economy. Wildlife tourism can be a key factor in supporting the conservation of the natural and cultural heritage of a country. It generates the funds that can be used directly to help meet or offset the costs of conservation, maintenance of cultural traditions and provision of education. Indirectly, wildlife tourism can bring to a country the public and political support for conservation. Local communities benefit through maintenance of their traditions and values and therefore the industry creates greater pride in the community. 4.4 Making wildlife tourism sustainable Developing a sustainable wildlife tourism strategy requires that the conditions for the industry to continue as an activity in the future are right through proper policies. It should also take into consideration the ability of society and the environment to absorb and benefit from the impacts of tourism in a sustainable manner. I present here a brief account of the key aspects of the economic, social and environmental impacts of wildlife tourism that can make it more sustainable. 4.4.1 Economic viability The viability of a wildlife tourism industry depends on success of the wildlife tourism businesses in providing benefits to local communities. For sustainability, policies should be directed at creating a good trading atmosphere, maintaining and projecting an attractive destination, understanding the needs of customers and satisfying their needs. 4.4.2 Social equity Wildlife tourism policies should target disadvantaged groups such as the poor so as to create equitable distribution of economic and social benefits. This can be achieved through creating policies that empower disadvantaged groups to 14 develop or participate in income generating activities such as supply of goods and services. Policies should also ensure that income generated from wildlife tourism is used to support social development programs such as health care, education, and social and community projects. 4.4.3 Biodiversity conservation Wildlife tourism activities should support the conservation of wildlife and its habitat and minimize damage. Part of the income generated should be used for conservation programs in the destination in order to maintain its appeal to visitors. The industry should increase visitor awareness and support for conservation. It is important that government policy is directed at promoting development and management of wildlife tourism given that its practice conserves the environment and sustains the wellbeing of local people. For sustainability, policies should be directed at minimizing damage from wildlife tourism to areas where biodiversity may be vulnerable, raising visitor awareness and appreciation of biodiversity and raising support for conservation from visitors and enterprises. 4.4.4 Environmental purity Maintaining environmental purity entails reducing waste and harmful emissions to the environment so as to preserve the quality of the air, water and land on which the wildlife depend. Policies should promote reduction in the use of environmentally damaging chemicals, avoiding the discharge of sewage to water catchments, minimizing waste or proper disposal, influencing the establishment of facilities and encouraging the use of more sustainable transport. 5.1 Implementing a sustainable wildlife tourism strategy for South Sudan South Sudan’s wildlife has had little influence in the lives of the people managing it or living with it. Since the inception of the concept of preservation based on the Wildlife Ordinance of 1935 which created protected areas, there has never been a serious attempt at developing a strategy for proper utilization of wildlife in the region. To date, no protected area has had or used a management plan. This lack of vision and strategy has led to neglect of scientific principles of wildlife management and elevation of the law enforcement aspect of it. As a result, wildlife, a resource that has changed the livelihoods of many poor people and their economies in many Sub-Saharan African states has become a liability to both the government (cost of management) and the local communities (denial of access to the resource) on whose land protected areas are established. 15 For most of the post independence time, South Sudan has been a battle field and successive governments sanctioned from Khartoum, did little to develop the resources of the region because most were castrated and the others were handicapped. During this time, wildlife in particular, suffered the most because the development of its preferred income generating sector -tourism requires a secure environment in which the climate for investment is good. Now that peace has come to South Sudan, the task of changing the status quo lies squarely on the shoulders of policy makers in the Government of South Sudan assisted by the sons and daughters of the region, who over the years have acquired skills all over the globe but had no chance of using them. A collective action is needed if we are to realize the UN MDG of eradicating extreme poverty and hunger and our own vision of taking towns to villages. It is important that every resource with potential to alleviate poverty is utilized if we are to meet the set goal of reducing poverty by half come 2015. As South Sudan will start from zero, our first priority will be to lay the foundation for a sustainable tourism industry by establishing the institutional structures and regulations by which we operate. The development of infrastructure and superstructures for tourism along with support facilities form the core of the development process for the industry. 5.1 Recommended action programs for developing a sustainable wildlife tourism strategy for South Sudan. From the analysis of the state of tourism country wide, South Sudan, the home of Sudan’s wildlife was left out from all tourism development programs originating from the central government. Only consumptive wildlife tourism (game hunting) was practiced in the region during the Regional Government era of the 1970s. As we proceed to develop an Environmental Management Plan for the country and South Sudan in particular, the neglect of the wildlife sector requires reversal. A wildlife development program has to be factored into the plan knowing that the development of such an industry can have positive or negative impact on the environment. Our drive therefore should be to develop a wildlife tourism industry that is environmentally friendly, socially desirable and economically viable. In short, the industry developed must be sustainable. It is clear from the review that a sustainable tourism program can help alleviate the chronic issue of poverty in South Sudan while maintaining the existence of wildlife in the region. A broad outline of the action programs that the MEWCT need to undertake in order to initiate a sustainable tourism program for the region is presented. 16 1. Develop wildlife tourism objectives and policies The primary objective of a wildlife tourism program for South Sudan should be to develop an industry that can contribute to poverty reduction through generation of income and employment. In order to achieve this objective, government policies should be directed at; i) Ensuring economic viability and competitiveness of South Sudan as a wildlife tourist destination. ii) Seeking a widespread and fair distribution of economic and social benefits from wildlife tourism. iii) Supporting the conservation of protected areas, habitats and wildlife while minimizing damage from the industry to the resource base. iv) Minimizing the pollution of the air, water and land through reduced generation of waste and harmful emissions by tourism enterprises and tourists. 2. Strengthening institutions and economic linkages i) Public sector institutions The present organizational structure and staffing positions of the MEWCT requires improvement if a successful wildlife tourism industry is to be developed. The ministry and in particular the Directorate of Tourism is grossly under resourced in terms of manpower and funding. It is important for the government to embark on public sector institutional development for the industry. The linkage between the Directorate of Wildlife and that of Tourism must be defined and strengthened. ii) Strengthening linkages with states Currently, the linkages between the Directorate of Tourism at GOSS and state tourism authorities is not clear. Based on the CPA and the interim constitutions, states have a right to develop tourism programs. The same documents however do allow the Directorate of Tourism to create the legislation by which the states execute their tourism programs. It is important that the thin line dividing the two administrative and management set ups is clearly defined so as to avoid duplication and antagonism. This can be done by developing a tourism and hotels ordinance that defines the roles of each level of government and the rights and obligations of the private sector and tourists. iii) Strengthening linkages with the private sector The private sector comprising of hotel business, tourism agencies, airlines, tour operators and suppliers of tourism goods and services needs to be developed in 17 South Sudan if the tourism product in the region is to be complete. The government therefore needs to set policies which neither compromise standards nor intrude into the rights of the private sector. A conducive climate for investment for both domestic and foreign entrepreneurs must be created. iv) Strengthening linkages with other sectors of the economy In order to maximize the socio-economic benefits of tourism, the revenues generated from the industry must remain in South Sudan. Leakage of tourism revenues can be avoided by encouraging local sourcing of supplies, employment of local labor and support of locally owned businesses. 3. Improving access transport and infrastructure i) International air access Direct international flights to Juba are needed if visitors are to spend more time in South Sudan and visit parts of the region other than Juba. Currently, visitors come to South Sudan by way of Khartoum, Nairobi or Kampala. These indirect flights increase flight time and cost which can discourage potential customers. The airports in Rumbek and Malakal need to be upgraded to international standards and the capacity of Juba airport should be increased to handle heavier traffic. ii) Internal access In the tourism industry, customers need to get to places they would like to visit in reasonable speed, comfort and safety. The present road systems in South Sudan can not provide such luxury and hence deter progress. The MEWCT therefore needs to coordinate with the Ministry of Transport and Roads so that important links to protected areas are included in the road building program of the ministry. Specifically, the major access roads to Southern, Shambe, Badingilo, Boma and Nimule National Parks and the Sudd wetland need to be given priority. 4 Improving service standards i) Train-the-Trainer program The quality of the staff of the service sector needs a lot of effort to bring them to acceptable standard. This will not be possible if all the staff are to undergo formal training because of the cost, lack of specialized institutions and lack of time for a reasonable number of service providers to receive formal training. The best way out is to conduct a training needs assessment and select already skilled professionals in the various sectors of the industry and train them how to pass their skills to others on the job. The trainer keeps the job in the establishment he/she works in but acts as a catalyst for training. 18 ii) Develop tour guide and operator services The quality of tour guides is key to the success of a wildlife tourism industry. Wildlife tourism is a specialized form of tourism that requires professionalism as some of the tourists are themselves knowledgeable. Therefore a wildlife tourist guide needs to know the wildlife under his range, has to be sociable and balanced in personality. iii) Construct proper accommodation facilities For visitors to relax after a long flight to South Sudan, comfort must be provided in the major towns of the region. Each town should have at least one 3 star hotel in addition to lower category lodging. In the protected areas, lower grade lodging such as tents, bungalows and lodges constructed using local materials should be provided. 5 Creating greater market awareness In its present state, South Sudan is an unknown quantity in the international tourist market. Awareness of the regions wildlife tourism potentials is key to its development for both domestic and foreign tourists. The image of South Sudan as a wildlife tourism destination can be marketed through; i) Development of promotional materials such as documentaries and general tourist information material. brochures, maps, ii) Carrying out market research to understand potential customer perceptions, attitudes and holiday requirements. iii) Promoting South Sudan’s wildlife tourism potential through more pro-active use of the internet. iv) Setting up overseas representation of the business in identified main source markets and not relying on diplomatic and trade missions. v) Formulating a marketing strategy and plan based on a realistic and sustainable budget. 6. Improving security and personal safety Security and safety play a key role in a tourist’s choice of a destination. South Sudan has been insecure for most of the time Sudan has been independent. All effort should be exerted on protecting the CPA which to a large extent has brought some sanity to South Sudan. To improve security and tourism prospects in the region: 19 i) The Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), has to be disbanded through all possible means be it political or otherwise ii) All gun trotting militia youth need to be demobilized and sent to school so that they understand the fact that there are other better ways to a decent living compared to the harsh bush environment. iii) Tourists need to be assured that South Sudan is getting better by the day and the peace dividends are being felt even by wildlife. The reported return of elephants to their former range from wherever they have been in refugee or internal displacement is proof of this fact. The awareness program should be directly under the President of GOSS and Commander-in-Chief of the SPLA. It should involve all stakeholders of wildlife tourism. 5.2 CONCLUSION Over the last 5 years, the WTO estimates Sudan’s tourism sector to have grown by 6%. This growth however contributed just 0.3% to GDP and had little influence in the livelihoods of the rural poor as it was concentrated in the states of Khartoum and Port Sudan. Like all development oriented sectors in the country, South Sudan’s contribution to this growth was zero as its main attractions, the wildlife, was and is still inaccessible. Our drive therefore should be to create the structures and superstructures that can make the resource accessible to potential customers. Globally, it is recognized that wildlife plays a role in the livelihood of many poor people and therefore has been incorporated into government and donor policies of poverty reduction in many countries. So far, the best wildlife related approach to enhance livelihoods of poor people is tourism. Most of South Sudan’s Ecosystem still remains intact and unspoiled and thus provides a strong basis for sustainable wildlife tourism development. All that is required is proper planning and management of the available resources. It should be born in mind that sustainable wildlife tourism cannot thrive if we do not take care of our fragile environment. In this context, therefore, we should always remember the cardinal point that we all have a duty to practice responsible tourism so that at the end of the day we shall be able to conserve our fragile environment and biodiversity for the benefit of mankind. To this end there is therefore, an urgent need to put the necessary legislations and codes of conduct in place so as to ensure balanced development of wildlife tourism in South Sudan. Exchange of information and experience with neighboring countries would also be vital in achieving the required results for the development of sustainable wildlife tourism and conservation of the environment. 20 Table 1: Population Estimates of Large Wild Mammals in South Sudan Species Baboon Bushbuck Buffalo Duiker Elephant Mongalla Gazelle Girrafe Lelwel Hartebeest Hippopotamus White-eared Kob Uganda Kob Nile Lechwe Oribi Reedbuck Roan Antelope Sitatunga Tiang Waterbuck Zebra Giant Eland White Rhino Warthog South Sudan1 320,000 133,000 326,000 180,000 1,000,000 750,000 18,000 - Southern National Park2 1,148 269 60,850 10,940 1,325 8,132 111 472 685 1,043 2,580 118 168 2,213 Sudd Wetland3 268 4,501 234 2,964 65,937 4,527 234 2,252 11,672 2,489 32,279 6,006 33,380 4,124 1,108 359,496 8,851 3,889 - Watson, F.H. (1977) Sudan National Livestock Census and Resources Inventory Report. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, Khartoum 1 2 Boitani, L. (1981) The Southern National Park. A Master Plan, Juba, Rome Howell et al., (1985) The Jonglei Canal. Impacts and Opportunities. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge 3 21 References Ashley, C., Roe, D. and Goodwin, H. (2001) Pro Poor Tourism Strategies: Making Tourism Work for the Poor. Overseas Development Institute and International Institute for Environment and Development. Asibey, E.O. and Child, G.S. (1990) Wildlife Management for rural development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Unasylva 41:161 Boitani, L. (1981) The Southern National Park. A Master Plan, Juba, Rome Howell et al., (1985) The Jonglei Canal. Impacts and Opportunities. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge Nimir et al., (2003) A Management Plan for Dinder National Park. UNDP/GEF project SUD / 98 / G41. Tomor, B.M. (2006) The state of ecotourism in Dinder National Park, Sudan. Journal of Natural Resources and Environmental Studies 4: Watson, F.H. (1977) Sudan National Livestock Census and Resources Inventory Report. Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Natural Resources, Khartoum Weinberg, A., Bellows, S. and Ekster, D. (2002) Sustainable ecotourism: Insights and Implications from two successful case studies. Society and Natural Resources 15: 371-380. World Tourism Organization (2003) Assessment of the results achieved in realizing the aims and objectives of the International year of Ecotourism 2002. WTO Report to the United Nation General Assembly. World Tourism Organization (2005) Annual Report. Accessed at www.worldtourism.org World Travel Council, 1999, Measuring Travel and Tourism Impact on the Economy. Yunis, E. (2004) Sustainable Tourism and Poverty Alleviation. WTO Report to the World Bank. 22