Selfishness, Self-Interest and Self-Love

advertisement

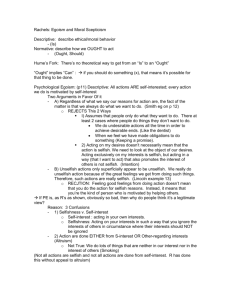

Selfishness, Self-Interest, and Self-Love Too much self-interest becomes selfishness. But…too much little self-love – in business as elsewhere – shows a lack of spirit and backbone, which is not approved.1 John C. Wood Mezgebu K. Feleke & Johan De Tavernier ABSTRACT This article illuminates the difference between the act of selfishness, self-interest and self-love, usually confused and overlooked in ethical discourses. In the contemporary economical and social life human behaviour is dominated by self-interest. From a Christian viewpoint most ethicists criticize self-interest as a ‘narrow’ view that could ingeniously embrace harmful selfishness. Do we agree with them? Though we consider its importance as a primary motive for acting in market economical and political affairs, we argue that ethical standards basically require a moral outlook that goes beyond the dominant self-interest model. Since most people have both a benevolent and selfinterested attitude, we view self-love as indispensable for cooperation and social behaviour. Christian love essentially unites persons with the ontological good – originated from God – and transforms the self to be concerned both for oneself and the good of others on the level of identity. This article presents a more subtle critical analysis of self-interest – an sich a-moral - while it proposes self-love not only as a necessary condition to undertake genuine morality but also as a guarantee for the moderation of self-interest. KEY WORDS: Agape, love, self, self-interest, selfishness, self-love. Introduction In most ethical discourses, one may observe confusion between an act of selfishness, selfinterest, and self-love. Some seem to intentionally mystify their meaning while others inadvertently employ them interchangeably to explain one’s act in relation to oneself. Moral philosophers, like Ayn Rand, resolutely defines selfishness in a morally neutral sense as concern with one’s own interest while it has been described by the majority of moral philosophers as being concerned excessively or exclusively with oneself without 1 John C. Wood, Adam Smith: Critical Assessments, Vol. I (London: Taylor & Francis, 1993), p. 345. 2 regard for the well-being of others, which recalls moral evaluation.2 Some moral theologians, like Paul Tillich, interpret self-love in a morally neutral sense as “natural self-affirmation” that we argue best expressed by the concept of self-interest. Others, like Joseph Butler, employ particular adjectives such as “reasonable self-love” or “cool selflove” to imply the positive meaning of the term, and “immoderate self-love” or “excessive self-love” to refer to its negative meaning.3 Psychologists like Samuel Vaknin sometimes use the phrase “healthy narcissism” to distinguish a mature, balanced love of oneself from “over-valuation of the ego” that connotes selfishness.4 Our contention is that the notions selfishness, self-interest, and self-love do not explain the same moral identity. In fact, as they characterise the act of a person from the standpoint of his/her attitude toward him/herself, they can be employed to generally describe any dispositions that imply the advantage of the individual. But when they appear in moral discourses, they must be reflectively evaluated in terms of their own distinctive nature. The demand of making this distinction comes from the fact that excessive and exclusive concern to oneself could inevitably lead people into conflict, violence and war. As Thomas Hobbes pointed out, people find themselves in a perpetual state of war of “all against all” due to the motivation of acting in accordance with selfinterest.5 Today the culture of egoism unavoidably creates a reality of violence in all forms of life – family, social relations, and among ethnic groups and nations. As it encourages people to develop an instrumental approach to each other, the self-relational action of the individual, group or nation causes to treat others violently, be it in a cruel or a more friendly and subtle way.6 Since a self-related action has brought about negative consequences in human relationships, there is something erroneous with one’s attitude towards oneself that can be explained through distinguishing the act of selfishness, selfinterest, and self-love. In the first section, we explain the negative consequence of a selfish act. The second critically reflect on an act of self-interest that is accepted and defended by some moral philosophers as an act of morality. In the third section we analyse and propose self-love as an important moral concept to explain a self-related action from a theological perspective. Through the discussion, an attempt will be made to evaluate and demonstrate the specific place of each concept in moral discourse. 2 Ayn Rand & Nathaniel Branden, The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism, New York: New American Library, 1964, p. x; see ‘Selfish’, ‘Self-Interest’ and ‘Selfishness’ in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, New York: Merriam-Webster, 11th edn, 2003, p. 1128. 3 Paul Tillich, Ultimate Concern: Tillich in Dialogue, (ed.) Donald Mackenzie Brown (New York: Harper & Row, 1965), p. 206; Joseph Butler, Sermons, (ed.) Samuel Clarke, Boston, 1827, p. 153. 4 Samuel Vaknin, Malignant Self Love: Narcissism Revisited, Skopje: Narcissus Publishing, 2003, p. 87. William W. Meissner, The Ethical Dimension of Psychoanalysis: A Dialogue (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2003), p. 149. Linda Backman, Bringing Your Soul to Light: Healing Through Past Lives and the Time Between, Woodbury, MN: Llwellyn Worldwide, 2009, p. 173. 5 Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, New York: BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2009, pp. xiii-xiv. Cf. 6 Gary Acquaviva, Values, Violence, and Our Future. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2000, 23-25, 43-53. 3 1. Self and Selfishness The attempt to explain the distinctive nature of the three concepts – selfishness, selfinterest and self-love – immediately takes us to their common root term, namely, “self” or “ego”. The self, in Greek egoo and Latin ego, for the English “I”, indicates the centre of one’s being or one’s conscious experience.7 The word “ego” or “self” refers to the central element of human faculty by which the individual realizes his/her existence. This implies that the self dominates the individual’s mode of thinking, way of acting and style of living. Highlighting this point, Simon Blackburn defines the ego as “the thinking, active self; the self conceived of as the organizing and continuing subject of experience and the author of action”.8 It is the ego that determines what to think and how to act through which it defines itself in a sort of experience that gives meaning for its existence. The ego or self enables us to perceive the world and situate ourselves in it because it performs the whole controlling and integrating function in the human personality. While the role played by the ego in managing personal identity has to be seen as natural and healthy, a rather exclusive orientation towards oneself, usually typified by the term selfishness, is subject to moral evaluation. Selfishness is widely defined as “exclusive interest in the self” and “excessive self-regard”.9 A selfish concern or disposition originally evolves from the self that perceives everything in relation to itself only for the advantage of oneself. It is an inordinate concern to satisfy one’s own desires and fulfil one’s own needs. Once the person recognizes the self as an entity in his/her existence, the selfish motive naturally and inevitably raises a feeling of “mine”, an idea of self-possession or putting something under one’s belong. As Kant stated, “from the day a human being begins to speak in terms of ‘I,’ he brings forth his beloved self whenever he can and egoism progresses Norman Geisler, ‘Egoism’, in David John Atkinson, David Field, Arthur F. Holmes, Oliver O’Donovan (eds.), New Dictionary of Christian Ethics and Pastoral Theology, Leicester: Inter-Varsity Press, 1995, p. 336; Fraser Watts & Mark Williams, The Psychology of Religious Knowing, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988, p. 96; John Maltby, Liz Day, Ann MacAskill, Personality, Individual Differences and Intelligence, Harlow: Prentice Hall, 2007, p. 54. 8 Simon Blackburn, The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994, p. 114; Sharon Griffin, ‘Ego’, in James Childress (ed.), The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Ethics (Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox Press, 1986), p. 185; see also Donald K. McKim (ed.), Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996, p. 87. ‘Self’ is the central English term that explains the word ‘ego’ in most references. ‘Ego’ and ‘self’ are employed to describe the inner most personality of the individual who is responsible for thinking, acting and living for oneself. 9 John MacQuarrie, ‘Egoism’, in Childress (ed.), The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Ethics, p. 185. William Sorley, ‘Egoism’, in James Mark Bladwin (ed.), Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, New York: The MacMillan Company, 1901-1905, p. 312; Bertrand Russell, ‘Egoism’, in Robert Audi (ed.), The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995, p. 218. 7 4 incessantly”.10 The more one is obsessively concerned to the self and act accordingly, the more the feeling of selfishness will arisen fully and develop powerfully. Selfishness thus consists in a disposition or choice to exclusively and excessively gratify one’s propensities and feelings. Its concern or disposition, in fact, is not wrong in itself but the negative impact it creates on others that shades the act with vile.11 Michael Mok opines that “when we say that a person is selfish, we usually mean that he has no concern of other people; that he is interested in himself and himself alone. If [this is] so, the correct usage of selfishness should be ‘the absence of interest in the interest of other agents”’.12 As a selfish person is only interested in and wants everything for oneself, he/she feels no pleasure in giving, but only in taking. The person can see nothing but one’s own self and judges everyone and everything from its usefulness to him/her. A selfish person, as Joseph Hester says, is “[the one] who is determined to promote his or her own good or interest even beyond the morally permissible. [He or she is] a person who considers himself or herself first and only, who does not restrain his or her own pursuit of the good in situations when his or her own good conflicts with others’”13 For this reason selfishness is regarded as “the natural enemy of other-regardingness (and hence morality)”.14 Selfishness is not only lack of interest in the needs of others but also lack of respect for the dignity and integrity of others. What makes an act selfish is not the fact that it is self-relational but because it does not really consider the well-being of others. For this reason, “it is fundamentally destructive to any relationship”.15 The common public motto ‘do not be selfish’ is not only a simple moral instruction but also an indication of losing the human sense of being in oneself and others in the act of selfishness. As an anti-social and a self-defeating attitude, it has strongly been reproached by almost all world religions. Most religions identify egoism as the source of all conflicts and demand the individual to get out of the cocoon of “the little self” in order to reach ultimate freedom. Since they indicate the ego as the root of separation and unrest within oneself, and with others, they justify the achievement of good religious experience and 10 Immanuel Kant, Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View, trans. Mary J. Gregor, The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1974, p. 10. 11 McKim (ed.), Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms, p. 254. 12 Michael Chau-Fong Mok, Ethical Egoism as a Moral Theory, Taipei: Institute of the Three Principles of the People, Academia Sinica, 1983, p. 11. 13 Joseph P. Hester, The Ten Commandments: A Handbook of Religious, Legal and Social Issues, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003, p. 60. 14 Richard H. Jones, Mysticism and Morality: A New Look at Old Questions, Lanham: Lexington Books, 2004, pp. 35-36; James Bernard Murphy, ‘Practical Reason and Moral Psychology’, in Ellen Frankel Paul, Fred Dycus Miller, Jeffrey Paul (eds.), Moral Knowledge, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 286. 15 Fred Lowery, Covenant Marriage: Staying Together for Life, West Monroe: Simon and Schuster, 2002, p. 207. 5 moral perfection in terms of overcoming the attitude of ego.16 The anti-social effect of selfishness has also been noticed and criticised in some works of social philosophy. The well known German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer alleges it as “the sole source of failures to act morally, the source of all wrong-doing; of, that is, all infliction of suffering on others, all denial of their wills”.17 For Schopenhauer, egoistic attitude could lead the person to wickedness and the crime of every sort.18 The French sociologist Emile Durkheim calls it “the lower side of homo duplex [a human being as an antagonism between the desire to follow societal needs and instinctual desires of the human animal]”.19 He describes it as “a disease of the intellect, withdrawing us into a ‘phantasmagoric’ self and away from attachment to others and a milieu”.20 For Durkheim selfish attitude is a lamentable social product and pernicious. Selfishness makes people unhappy and perhaps cruel. As it divorces people from all sorts of life-enhancing social commitments and relations, selfish acts are destructive for others as well as oneself. 2. Self-Interest As we have noted above, self-interest is defined as being concerned to one’s own interest or advantage. Since the individual has been given a paramount place in explaining the reality of life within humano-centric worldview, the Western ethics highly emphasizes and strongly advocates morality within self-interest. Among them, Baruch Spinoza views preserving one’s being or activity – conatus essendi – as the ultimate principle of our nature and the basis of all virtuous acts. For Spinoza living in accordance with one’s nature is rationally seeking one’s own advantage which is also a practice of morality. He considers self-interest as a great social asset because selfish acts would be advantageous both for him/herself and others.21 This view of self-interest has been highly advocated by the founding father of the free market philosophy Adam Smith. His famous quote is: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their Helena Cristini, ‘Beyond Politics’, in Allan Eickelmann, Eric Nelson, Tom Lansford (eds.), Justice and Violence: Political Violence, Pacifism and Cultural Transformation, Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005, pp. 221-223. 17 Arthur Schopenhauer, On The Basis of Morality, trans. E.F.J. Payne, New York: Cosimo, 2007, p. xxii. 18 Schopenhauer, On The Basis of Morality, p. 79; cf. David E. Cartwright, Historical Dictionary of Schopenhauer’s Philosophy, Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2005, p. 12. 19 Stjepan Gabriel Mestrovic, Emile Durkheim and the Reformation of Sociology, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 1993, p. 65. 20 William Watts Miller, Durkheim, Morals and Modernity, Montréal: McGill-Queen’s Press – MQUP, 1996, pp. 132-133; Mark S. Cladis, A Communitarian Defense of Liberalism: Emile Durkheim and Contemporary Social Theory, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994, pp. 82, 280. 21 Benedict de Spinoza, The Ethics, New York: Classic Books International, 2008, pp. 164, 191. Cf. Benedictus de Spinoza, Spinoza: Complete Works, ed. Michael L. Morgan, Transl. Samuel Shirley, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2002, p. 333. 16 6 humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages”.22 The crucial message of this text is that by seeking their own well-being, individuals provide not only their own but also the public well-being. In other words, if we wish the goods that the baker has to offer us, it is not his/her humanity that we should address ourselves but the baker’s self-interest.23 Through this perception of economic relations Adam Smith attempts to ensure that acting on self-interest has beneficial outcomes both for oneself as well as society as a whole. The point is that individuals are best able to follow their own rationale and in pursuing it, they achieve unintentionally the bonum commune in a more effective way than if required by public policy.24 Having this premise behind, in the contemporary moral discourse, a number of moral philosophers defend the morality of a self-interested act. Criticizing the widely held claim of moral impartiality and impersonality, they argue that ethics must be explained egoistically. For Tara Smith, what creates a sense of morality is not any value attributed to life in general but only the person’s self-interest. She argues morality as essentially egoistic; “Egoism is infused in morality from the outset, in the very nature of value and the logic of its pursuit. There is not one argument for morality and another argument for egoism. Rather, the selfish purpose of securing one’s life establishes the answers to all of morality’s more particular questions concerning what constitute virtues and vices and how a person should act”.25 Since egoism is not a social policy, she insists that the fundamental mandate for morality stems not from acting in relation to others or considering the existence of other people but from the basic requirements of living for oneself. Other defenders of this position even argue that there is a possibility of identifying oneself with others within the realm of self-interest. Richard Volkman asserts that “an egoist can and should value and identify immediately with the welfare of friends, family, and even some perfect strangers”.26 His basic argument is that if one takes special interest in the interests of those he/she loves, (for instance, a husband in his wife or son), one’s life will go better. He considers such cases as “deep and immediate concern for other people”. Lester Hunt raises a reasonable question: “how the good of others can become good for oneself in a non-consequentialist way?” Yet in his attempt to answer, he seems to suggest a reality that could not in fact substantiated from an act of self-interest: “Although my friend’s body does not overlap my body, his life does overlap my life. Beyond that, many of the other events in my friend’s life, the ones in which I do not share as fellow-agent, 22 Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations Books I-III, contr. Andrew Skinner, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1982, p. 119. 23 David L. Schindler, ‘Neoconservative Economics and the Church’s “Authentic Theology of Integral Human Liberation”’, in Charles Curran, Richard McCormick (eds.), John Paul II and Moral Theology, Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1998, p. 346. 24 Michael Novak, Free Persons and the Common Good, New York: Madison Books, 1989, pp. 55-69. 25 Smith, Viable Values, p. 155. 26 Richard, Volkman, ‘A defense of Eudaimonist Egoism’, in Laura V. Siegal (ed.), Philosophy and Ethics: New Research, New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., 2007, p. 287. 7 are things of which I am conscious, and my well-being is raised or lowered by this consciousness. For these reasons, good things in my friend’s life will be goods in my life as well”.27 He tried to bring into vision the goodness of his friend to him not in terms of a valuable object but of the characteristic of his life, of the way he lives and functions. The fundamental question is: how far a self-interested attitude and action could enable the person to identify him/herself with others? How does unintentional consequence of helping others could genuinely justify the morality of a self-interested act? §§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§§ Self-interest seems to be an ambiguous concept. When the concept comes to be used as a ground for human relationships, it significantly challenges moral reasoning.28 To demonstrate the place of self-interest in morality, we need to distinct, based on the above arguments, three different implications, namely, (1) doing something only for oneself without any positive or negative consequences for the well-being of others; (2) doing something for oneself with the sole intention of considering oneself, and helping others unintentionally as a side effect of one’s action to oneself; (3) doing something for oneself with the full intention of considering or helping others out of identifying them with oneself. There is a huge difference between these three cases. The distinctive mark that differentiates one from the other is the motivation or intentionality of acting. The second and third cases are based on the first one. Viewing only unintentional positive consequences of a self-interested act for the well-being of others, moral philosophers rationalize and justify the morality of self-interest. While the second case claims that the well-being of others is indirectly embraced in a self-interested act, the third case, going beyond, presumes that there is a direct and immediate relation of the self with others within self-interest. In this discussion, after we briefly stress the moral neutrality of a self-interested act, that is, the claim of the first case, we put into question the plausibility of the later two views which are strongly held and defended by the above mentioned moral philosophers. The first case is an attitude which is morally neutral for we are naturally motivated to satisfy anything that promotes our own welfare. As it looks for one’s own advantage and moves the person to be engaged in a rewarding act, most agree with this claim as what we mean by the concept of self-interest.29 We do a number of things to Lester Hunt, ‘Flourishing Egoism’, in Russ Shafer-Landau, Ethical theory: An Anthology, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007, p. 208. 28 The ongoing debate about self-interest reflects the strong challenge the notion of self-interest created in contemporary moral reasoning. See Paul Bloomfield (ed.), Morality and Self-Interest, New York: Oxford University Press, 2008. 29 Richard B. Brandt, Morality, Utilitarianism, and Rights, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992, p. 163. Stephen Finlay gives us the following definition of self-interest: “an action is in my self-interest 27 8 make our life happy, develop our ability to make progress in life, maintain our good health and want to have a life marked with significant achievement. Mark Waymack states, “We are also endowed psychologically with a strong streak of self-interest, but self-interest, in and of itself, is morally neutral. In another words, there is nothing morally wrong with pursuing self-interest as long as it does not violate benevolence”.30 These things could not strictly be considered as a-moral as such but rather have to be seen as the promotion of pre-moral values. According to L. Janssens pre-moral values such as life, physical and mental health, friendship, scientific knowledge, technology, arts, etc. – called traditionally bona physica – are not an sich moral or amoral, but the way we promote them in our acting is very important.31 At the same time we should avoid as much as possible pre-moral disvalues (mala physica) such as hunger, thirst, pain and suffering, mental illness, violence, exclusion, etc. We call them pre-moral because persons could be acting highly ethical even if they are suffering illness. Nevertheless it is in the person’s self-interest to promote as much as possible pre-moral values and avoid as much as possible pre-moral disvalues. Second, theologically speaking, we simply judge the second case as it does not belong to a moral action at all, for the reason that the claim does not fulfil what usually is referred to as the “three fonts of morality” that determine the moral nature of human action, namely, intention (finis operantis), the act-in-itself (finis operis), and the circumstances.32 The later two features of morality are called the external part or the material elements of the moral action, while the first one is the internal part or the formal element. As the end on which the whole purpose of our action depends, it is the intention that gives personal meaning to the action. In the words of Gula: “we cannot judge the morality of the physical action without reference to the meaning of the whole action which includes the intention of the agent. Intention is part of the objective act, or the act taken in its totality. It is neither a mitigating factor nor an accidental extra; rather, it is constitutive of the meaning of the action. Unless we consider the intention and the physical action together, we are not dealing properly with a human action as a moral (good for me) just in case and to the degree that it promotes a life containing intrinsically rewarding pursuit and/or accomplishment of goals that I strongly and intrinsically care about at the time of my pursuit/accomplishment of them”. Cf. Stephen Finlay, ‘Too Much Morality’, in Bloomfield (ed.), Morality and Self-interest, p. 149. 30 Mark Waymack, ‘Francis Hutcheson: Virtue Ethics and Public Policy’, in Jennifer Welchman (ed.), The Practice of Virtue: Classic and Contemporary Readings in Virtue Ethics, Indianapolis: Hackett, 2006, p. 171. See also David Gauthier, ‘Artificial Virtues and the Sensible Knave’, in Stanley Tweyman (ed.), David Hume: Critical Assessments, London: Routledge, 1995, p. 142; Edward Jarvis Bond, Ethics and Human Well-being: An Introduction to Moral Philosophy, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 1996, p. 8. 31 Louis Janssens, ‘De zedelijke normen’, in Jos Ghoos et al., Ethische vragen voor onze tijd. Hulde aan Mgr. V. Heylen, Antwerpen-Amsterdam: De Nederlandse Boekhandel, 1977, pp. 40-41. 32 Timothy E. O’Connell, Principles for a Catholic Morality, New York: The Seabury Press, 1978, pp. 169170. 9 action”.33 A self-interested act might be advantageous for the well-being of others. However, since the others are not originally intended in the mind of the agent, the action is not morally inevitable. One may reasonably argue the consideration of one’s own wellbeing as the intention of a self-interested action. In fact, our self-regard attitude is indispensable and worth of consideration as the intention of our moral action. Since doing things according to our interests is an activity of our freedom that defines our humanity, taking care of oneself cannot be neglected. However, the fact that we are not isolated but communal beings who interact in the web of complex personal and social relationships makes others to be considered as a determining factor in the content of morality. Daniel Maguire and Nicholas Fargnoli rightly assert that “at the fundamental level of ethics it could be pointed out that we are social beings by nature, not by convenience or contract. The fundamental moral experience of (1) the value of self, (2) the value of all others, and (3) the connection between 1 and 2 sets the stage for such a discussion”. 34 It is the being or the presence of others that have made morality the concern of our issue. Our acts will be evaluated as morally right or wrong in relation to our intention; we will be justified as good or bad persons based on the intentional effect on others as a consequence of our self-interested actions. In that case, is Richard Jones not right in notifying: “the issue for morality is whether we have taken into consideration the welfare of others for their own sake, regardless of whether our own welfare is enhanced”.35 Third, as a self-interested act does not recognize others on their own being, the person could not identify him/herself with others. Since self-interest subjectively means being self-focused or holding an ineliminable reference to one’s self, and objectively having an intrinsic motivation toward the well-being of one’s own life from one’s own point of view over the course of one’s whole life, the nature of the attitude does not enable the person to think and act transcendentally. In order to identify oneself with others, one is necessarily required seeing the good in the being of others and going beyond oneself for identification. In the realm of self-interest where one is strongly attached to him/herself, one is not able to identify him/herself with others. Our argument is not merely to explain this disability rather, to display that the act inevitably opens the possibility of adapting an instrumental attitude toward others.36 Reflecting on this nature of self-interest, Alexander Wendt explicitly indicates that there is a dichotomy between ‘self’ and ‘others’ in which the later is instrumentally used by the former. For Wendt, 33 Richard M. Gula, Reason Informed by Faith: Foundations of Catholic Morality, Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1989, pp. 265-267; cf. Linda Hogan, Confronting the Truth: Conscience in the Catholic Church, London: Darton, Longman and Todd Ltd, 2001, pp. 73-75. 34 Daniel C. Maguire and A. Nicholas Fargnoli, On Moral Grounds: The Art/Science of Ethics, New York: The Crossroad Publishing Company, 1996, p. 68 35 Richard H. Jones, Mysticism and Morality. A New Look at Old Questions, New York: Lexington Books, 2004, p. 36. 36 Stephen Finlay, ‘Too Much Morality’, in Bloomfield (ed.), Morality and Self-Interest, p. 138. 10 “self-interest is a belief about how to meet one’s needs – a subjective interest – that is characterized by a purely instrumental attitude toward the other: the other is an object to be picked up, used, and/or discarded for reasons having solely to do with an actor’s individual gratification”.37 His point of critique is that if the distinction between self and other is total, others have no intrinsic value for the self, and far from any sense of identification, they can be helped or used at the interest of the self. This informs us that a self-interested person is conscious about others’ interests but since his/her sole intention is seeking his/her own advantage, we should not imagine that he/she is committed for the common interest out of self-identification with others. If we are convinced of this argument, self-interest, which is an sich a morally neutral concept, seems to be another explanatory term for the idea of selfishness that we evaluated as destructive and immoral. In that case, the second form of a self-interested act leads people into conflict and violence. Therefore, our conclusion is that though a self-interested act could appear to help acting for the good of others, as it does not basically recognize the others from their perspective, we are suspicious of its importance for explaining the genuine sense of morality. Further, we presume that there might be a subtle form of selfishness that could be embedded in the act of self-interest. 3. Self-Love In most works of ethical scholars, self-related actions are also explained by the concept of self-love reflecting the negative, neutral, and positive aspect of the action. Aristotle, in Nicomachean Ethics, speaks of self-love as it can serve for vicious and virtuous acts. Anyone who loves him/herself beyond the reasonable limit is censured and rejected for being or doing so. He also speaks of virtuous people as proper self-lovers who neither do harm others nor themselves. So far as one does not hurt others for the sake of gaining for oneself, one will not be blamed or charged as a self-lover.38 As provided in the view of Oliver O’Donovan, Augustine gives three interpretations of self-love that refers to negative, neutral and positive dimensions of human action.39 Joseph Butler, in his Sermons, equates self-love with the idea of selfishness which he defines as an ‘immoderate or excessive’ self-love, an excessive calculating concern for one’s own interest or advantage.40 He also considers a kind of ‘reasonable’ or ‘cool’ self-love in agreement with taking care of the interests of others. For Butler the call of benevolence acting for the sake of others - is not contrary to self-love: “there is no peculiar contrariety 37 Alexander Wendt, Social Theory of International Politics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003, pp. 239-240; italics original. 38 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. Terence Irwin, Indianapolis: Hackett, 1985, pp. 146-47. 39 Oliver O’Donovan, The Problem of Self-Love in St. Augustine, Yale: Yale University Press, 1979, pp. 90, 91, 137. 40 Joseph Butler, Sermons, Samuel Clarke (ed.), Boston: 1827, p. 153. 11 between self-love and benevolence, no greater competition between these than between any other particular affections and self-love”.41 In the sense of its neutrality, Kant asserts that one must not give up his/her claims to his/her own happiness because under certain circumstances, it may even be a duty to be concerned with it, partly because health, wealth, and the like may be necessary means for the fulfilment of one’s duty, partly because the lack of happiness – when you are too poor for instance – can prevent one from fulfilling his/her duty.42 For this reason, Louis Janssens does not speak about the amorality of self-love but relates it to pre-moral values. Self-love, for Anders Nygren, is entirely pernicious and even ‘a devilish perversion’.43 His opposition against self-love is not only based on the distinction between the natural and divine love and non-believer and believer sorts of love but also on the fact that there is no proper consideration of others. These indications enable us to easily grasp how self-love is widely employed to explain the act of selfishness and self-interest. Our contention is that the notion of selflove must be entangled from sounding the meanings a selfish and self-interested actions. In order to better grasp its distinction from selfishness and self-interest we need to examine how self-love is conceived in moral theology. We judge that self-love is different from selfishness because it never implies excessive love for oneself to the extent of excluding and manipulating others. Rather it inclusively embraces others and identifies them as part of oneself. We also distinguish it from self-interest because an act of selflove seeks others’ advantage and motivates also oneself to see their well-being for their own sake. A strict theological understanding of self-love would contribute to this interpretation. The distinction is based on the distinctive nature of love which is essentially relational, always moves the person toward the good, and unites the person with God who is the ultimate good and the source of all goods. Let us briefly analyse this claim in the following three steps. First, self-love is, in its distinctive nature, in and of itself, relational. It basically requires others to constitute its sense and qualify its rightness or appropriateness. As Claudia Welz noted, “The only convincing mark of love is ‘love itself’, the love becomes known and recognized by the love in another”.44 This is to mean that love is essentially selfless and other-centred. Talking about love is always talking about an affective relationship between two or more human beings. The relationship is not simply an encounter but an exchange of meaning in the world of one with the other. Andreas Schuele rightly asserted that “the semantics of love become crucial above all in those contexts [Torah] where one opens one’s ‘own world’ to the other in order to create an 41 Joseph Butler, Human Nature and Other Sermons, Teddington: Echo Library, 2006, p. 54. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Practical Reason, trans. Werner S. Pluhar, intro. Stephen Engstrom, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2002,, p. 119. 43 Anders Nygren, Agape and Eros, trans. Philip L. Watson, New York: Harper and Row, repr., 1969, p. 740. See William McDougall, An Introduction in Social Psychology, London: BiblioLife, 2008, p. 139. 44 Claudia Welz, Love’s Transcendence and the Problem of Theodicy, Tübingen: Mohr, 2008, p. 114. 42 12 environment that meets with his or her requirements for life”.45 Love has the power of moving oneself toward others in search of the reality and meaning of life in human interactions. Love designates a particular form of self-relation in which we understand ourselves truly and rightly in our relations with one another.46 If love is understood as essentially relational, then self-love in the double love command, as Outka and Weaver display, must be conceived either (1) as a pre-condition for loving others in which one must love oneself in order to love others insofar as love for others entails some affirmation of the self as worthy of giving to another. (2) Or it must be understood as byproduct or a fruit of rightly loving others in which some goods (e.g., satisfaction, moral habituation, and discipline) may accrue to the self organically and indirectly. For Outka, “whatever spiritual wealth the self has within itself is the by-product of its relations, affections and responsibilities, of its concern for life beyond itself”.47 (3) Or, self-love must be viewed as a paradigm for neighbour love in which one loves others as he/she loves oneself. Outka affirms that “our self-love can serve as a model for what neighbourlove involves. We then transfer prudential reasoning into moral reasoning by invoking some variant of the Golden Rule”.48 Referring to this relational sense of self-love, Pinto states that “for humans ‘to be’ is essentially ‘to be with others’, to exist is to co-exist, to live is to live in relation to others. Hence all humans long for warm, loving, stable and fruitful relationships. Only by relating ourselves to others do we satisfy our personal, interpersonal and social needs. Love is the only way to enter into such relationships”.49 In this case, the independent claim of self-love as an immoral and a neutral position by itself, will be evacuated. But what is the essential substance or the basic element that moves the self toward others? What makes love a relational reality? Second, as its distinctive nature love tends toward the good. In the act of loving one is being united with a kind of ontological good which exists either in the self or others.50 In its broadest meaning, Thomas Aquinas defines love as “an aptitude for, or inclination toward, the good”.51 Inferring on the view of Aquinas, Stephen Pope explains, “At its deepest human level of meaning, ‘love’ refers to the agent’s ‘complacency in Andreas Schuele, ‘Sharing and Loving: Love, Law, and the Ethics of Cultural Memory in the Pentateuch’, in William Schweiker, Charles T. Mathews, (eds.), Having: Property and Possession in Religious and Social Life, Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 2004, p. 55. 46 Weaver, Self love and Christian Ethics, p. 1. 47 Reinhold Niebuhr, Faith and History: A Comparison of Christian and Modern Views of History, London: Nisbet, 1949, p. 117. 48 Gene Outka, ‘Agapeistic Ethics’, in Philip L. Quinn, Charles Taliaferro (eds.), A Companion to Philosophy of Religion, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 1999, p. 485; italics added. 49 Fr Joseph Prasad Pinto, Journey To Wholeness, Bandra: St Pauls BYB, 2006, p. 106.. 50 Gavin Hyman, ‘Disinterestedness: The Idol of Modernity’, in Gavin Hyman (ed.), New Directions in Philosophical Theology: Essays in Honour of Don Cupitt, Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004, p. 47. 51 Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Vol. II (Part II, First Section), New York: Cosimo, 2007, p. 701. 45 13 good’, a response of affective appreciation of an apprehended goodness”. 52 He elaborates that this appreciation could either be acceptance of, or conformity to, this apprehended good, or a desire for union with the unattained good or delight in the presence of the attained good. The central moral meaning of love is a willingness of the person to identify him/herself with the good in the reality. Self-love thus perceives the reality of being whether one’s own or others as good in itself. Loving oneself means identifying oneself with the being of good. G. Hyman asserts that “love of self has no justification and no intelligibility outside of a larger framework that connects the goodness of the self to the goodness of the whole. Love of self is both made possible by and is a necessary precondition for love of the whole, which is to say, a love of the good”.53 The claim is, if being is good, so too is the being of others and mine. Since the good is that which one naturally desires and can be known only as good for oneself, one loves oneself and others. Why the good in the self is identical with the good in others? What is the common ground for all goods in the whole reality? Third, the good to which the self tends to love is to be originally found in God, who is love himself. We saw that love means seeing the goodness in reality. The Scripture says “God saw that it was good” (Gn 1:31). This seeing, as a different one from human’s seeing of things, effects what it sees. This means that God’s seeing of the creation as good proves God’s goodness because God himself is the one who brought into existence the whole creation. If the goodness of creation proves God’s goodness, and love always seeks for the good, love is to derive from God and to be realized in others. Aquinas affirms that this good is to be found “in God as to its cause, in ourselves as to its effect, in our neighbour as in a similitude”.54 The good that ontologically exists in God is in the first instance accessible in oneself. As Carmichael asserts, “right self-love opens us to God and hence, in God’s love, to others”.55 This is a theological justification for selfaffirmation which is inextricably bound up with others for our genuine love for them. As Eric Johnson observes, “self-love can only properly be understood within the three personal dimensions of human life (God – others – self), and in terms of the redemptivehistorical meta-narrative (creation, fall and redemption)”.56 The theological sense of love is in essence to be received from the divine being and practically given to others. Selflove is basically constructed on viewing and accepting the ontological relational reality of Stephen J. Pope, ‘“Our Brother’s Keeper”: Thomistic Friendship and Roger Burggraeve’s Ethic of Responsibility’, in Johan De Tavernier et al. (eds.), Responsibility, God and Society: Theological Ethics in Dialogue, Leuven: Leuven University Press/Peeters, 2008, pp. 333-334. 53 Hyman, ‘Disinterestedness: The Idol of Modernity’, p. 48. See also Rufus Burrow, Jr. God and Human Responsibility: David Walker and Ethical Prophecy, Macer: Mercer University Press, 2004, p. 150. 54 Thomas Aquinas, The Treatise on the Divine Nature: Summa Theologiae I, 1-13, trans. Brian J. Shanley, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2006, p. 234. 55 Liz Carmichael, Friendship: Interpreting Christian Love, London: T&T Clark, 2004, p. 120. 56 Eric L. Johnson, Foundations for Soul Care: A Christian Psychology Proposal, Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2007, p. 559. 52 14 the self with God and others. It originates internally from God and is supposed to be externally shared with others. Self-love is, thus, a responding love that turns back to the self, after the self loves God with all its heart, soul and strength, and prepares itself to extend that divine love to others (Mt 22:36-40). At this point Schweiker rightly asserts that “one is to love [others] as one has first been loved by God, a love manifest in creation, in Christ, and in the reign of God. Christian self-love is grounded not in the self but in God. One’s being as a Christian is in Christ. There is an ‘otherness’ at the very core of any Christian conception of consciousness and the self”.57 Since our being in love with God enables us to love others, the one who loves God, also loves his/her brother (1 Jn 4:16-21). Since self-love is grounded ultimately not in the self but in God, loving God means realizing the love God shows us. In stead of saying that we love God and others as if love essentially originates from the self and is to be extended to others, we say that we respond to the love of God by giving this love to others. As in the thoughts of Schweiker and others, unless one first defines his/her identity with the divine being who is the cause of his/her existence, one never views the full sense of love. If this is not the case, then love of self could indeed become doubtful and even sinful. Self-love would easily degrade to either selfishness or pure self-interest. In other words, it gets out of the moral realm and takes the form of either immorality or amorality. Therefore, the theological sense of self-love reveals that an individual exists being ontologically related with God and others. This openness guarantees that self-love will not degrade to selfishness that entirely centred on the entity of the self, nor to pure selfinterest that only approaches others in terms of their significance to promote one’s own advantage. Johnson appropriately asserts that “loving God, others and self are interdependent, reciprocal and irreducible to each other, so that from a Christian standpoint, one cannot have one without some degree of the others”.58 Since our relation with the divine enables us to recognize the presence of others at the very core of our own conception of the self, our acts are not primarily directed to what is advantageous for us but to the good that will be realized in the trio-metaphysical realities (God, self, and others). Through divine oriented self-love one is able to perceive the reality of being as good in its profound dignity within oneself as well as within others. This realization of the good creates within the person a sense of humanity and sensitivity for the life of other human beings. The similarity between others and oneself, through the intermediation of God, permits us to exchange our love to one another. This theological perception of selflove that keeps in accord both the well-being of the agent and others would permit us to resolve rough human relationships and enable humanity to live in harmony and peace. 57 William Schweiker, Theological Ethics and Global Dynamics in the Time of Many Worlds, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2004, p. 103. 58 Johnson, Foundations for Soul Care, p. 559. 15 Conclusion Self-related actions are often called acts of selfishness, self-interest, or self-love without examining their distinctive nature. As we have seen, selfishness implies that the action is undertaken with an exclusive and excessive concern to oneself to the point of disregarding and manipulating the well-being of others. As it does not consider God and others as part of the self, a selfish act is anti-social and even self-defeating. Self-interest, apparently seeing its unintentional consequence for the good of others, is used as an explanatory term for moral behaviour. However, the discussion has made it clear that self-interest does not motivate the person to act directly for the good of others from their viewpoint. If the action is limited toward promoting one’s life without any impact on others, we judge that self-interest is descriptive and morally neutral. Yet if self-interest comes to be used for moral reasoning in relation to others, though it appears to be advantageous for others, the selfish motives could subtly be embedded in its root. Though it is often claimed as a kind of ‘rational’ or ‘enlightened’ self-interest, its inherent instrumental attitude toward others reflects a subtle form of selfishness that thwarts its relevance for morality. Since love is essentially relational – it leads one to be in union with others, self and God – self-love practically enables the person to consider others as part of one’s own identity. Theologically speaking, self-love always refers to one’s relation with others, to the being of good, and God who is love himself and the origin of existence. A Christian understanding of self-love keeps in accord both one’s own wellbeing and the well-being of others. As it makes one to develop sensitivity toward others, self-love perfects the genuine sense of morality that guarantees the true vision of humanity. As a distinctive concept from selfishness and self-interest, it should be restrictively employed to explain the genuine morality that always balances one’s relation with others for their peaceful and harmonious coexistence.