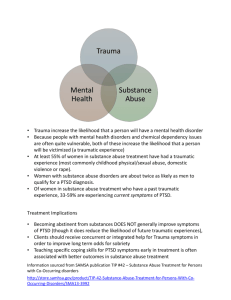

Substance Abuse Treatment for Persons With Child Abuse and

advertisement