The financial crisis is

advertisement

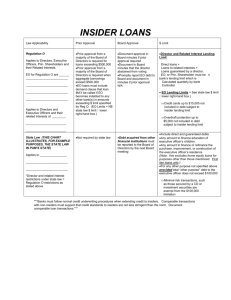

The unfolding financial crisis: What are the implications for developing countries? Josiah Johnston, October 10, 2008 ARE 253, International Economic Development Policy: International Public Policy Note #2 1. Background on the financial crisis The financial crisis began showing its teeth when major international banks and insurance companies began loosing solvency from holding too many bad loans, which brought about a widespread and rapid reduction in available credit. Also, the risk of financial institutions going bankrupt caused stock markets to fall precipitously. This crisis was brought about by many US homeowners defaulting on sub-prime mortgage loans with high interest rates. Between 2001 and 2006, bank relaxed criteria for home purchases, which flooded the housing markets with buyers, causing prices to steadily and rapidly increase. During that time, some borrowers had trouble meeting loan payments, but were able to sell their homes for a profit (due to the rising housing prices), so default rates were quite low. Because the default rate was low over multiple years, even for loans with high interest rates, arms-length investors pumped increasing amounts of money into the US mortgage markets, and those loans were traded extensively between international financial institutions. Around 2006, the stock of people willing to bid up the housing prices declined enough for supply to overtake demand and housing prices began falling. Consequently, people unable to repay loans could not sell at a profit or even break-even, and began defaulting. This trend became widespread and major financial institutions found themselves holding large amounts of bad debt that built up to such a point that financial institutions are loosing solvency. US and European national banks are dealing with the crisis by buying out bad debt, lowering interest rates [3], and in some cases, increasing personal savings protection and offering loan guarantees [5]. Financial institutions are reacting by reducing credit in general, and pulling investments out of developing countries to reduce their risks [4]. Several UN speakers have reacted by berating US and UK financial institutions for issuing such large amount of high-risk loans, disregarding warnings, and threatening global economic stability. 2. Impacts on Developing countries It does not appear that sovereign or private financial institutions in developing countries hold much of this bad debt, so it is unlikely they will be directly affected. Still, many developing countries will experience indirect effects that depend on how they are connected to international markets. The list of potential impacts is: Disinvestment. The BBC claims foreign investors are pulling out of fiscally sound Indonesian markets to reduce risk on their accounts. [4] Less available credit. The reluctance of lenders to take on any new risk will reduce the total amount of credit available. Decreased exports. Many purchasers f developing nation exports are dependent on short term credit and are directly impacted by the credit crunch. Until the purchasers adapt or are able to reaccess credit, exports of elastic goods will fall. Currency devaluation. The crisis has hastened the fall of the US dollar, so countries with currencies pegged to the US dollar will experience a loss in purchasing power in some international markets. Slowed poverty reduction. Aid from wealthy countries directed towards poverty alleviation and other Millennium Development Goals will likely be reduced. Increased debt payments. If the crisis continues to get worse, interest rates on floating interest loans will increase, and developing nations holding such loans will have higher bills. 3. Brady Bonds: what they are and lessons learned Brady bonds refer to a family of debt restructuring that occurred through the late 1980’s and early 1990’s in which indebted countries issued tradable bonds as repayment for outstanding loans [8]. The details were negotiated on a case-by-case basis, but certain themes were common. There was some debt forgiveness (either reduced principal or interest), which motivated debtors to participate. Lenders were motivated because a) the outstanding loans were non-performing and they had little to loose, b) the new bonds were frequently backed by securities while the outstanding loans usually lacked collateral, and c) the new bonds were tradable, which allowed lenders to diversify their holdings and reduce risk. The principal on the Brady bonds was typically secured by sovereign bonds denominated to match the debt (e.g. US treasury bonds for debt in US dollars). 1-2 years of interest payments on the bonds were often secured by highlyrated investments also held in escrow. The indebted countries paid for these various securities with liquid assets and new loans from the IMF or World Bank. A potentially important factor in the success of Brady Bonds was the willingness of major money centers such as the IMF and World Bank to take over some of the bad debt by lending money to purchase collateral on principal owed, and the willingness of other major money center banks to continue holding loan assets and associated risks. Brady bonds dominated Emerging Market debt trading in the mid 90’s but were replaced by other instruments such as global bonds over the following decade: they accounted for 61% of that market’s volume in 1994, but only 2% in 2005. [6] The context and stakeholders involved in the Brady restructuring do not have precise parallels in the current crisis. Still, two of the three main outcomes of the Brady restructuring may be applicable today: increasing the value of bad debt and debt restructuring. The third outcome, facilitating debt trading to reduce risk, is not highly applicable because the bad debt in question, sub-prime mortgage loans, is already structured for easy trading. Figure 1. Stakeholders involved in Brady Bond debt restructuring and transactions. Dollar values on outstanding loans and bonds are illustrative; bonds were rarely issued for less than $125 million USD, and lenders frequently accepted either 30-50% losses on face value or reduced interest rates fixed at belowmarket values [6]. According to EMTA, a financial industry trade association, most lenders that accepted Brady Bonds for outstanding loans were either smaller US commercial banks or non-US financial institutions rather than “major money center banks” [9]. The strategy employed by Brady restructuring to increase the value of the debt, increasing collateral by moving assets to escrow and accepting new third party debt, is not highly applicable to the current situation. During Brady restructing, much of the bad debt was not secured and was owed by sovereign governments rather than private entities. In the current crisis, most of the bad debt is secured by houses that are falling in value, and is ultimately owed by private citizens. Its unclear that increasing the collateral would make a significant difference in the debt’s value since collateral already exists, but investment in diversifying the collateral may compensate for the recent devaluation. The debtors now (a large number of homeowners) are different from the ones then (a small number of countries), but with a stretch, one can replace the role of indebted countries with indebted corporations since the current bad private debt is aggregated by certain financial institutions into larger sums they in turn owe to other financial institutions. One could then ask the indebted corporations to shift their assets to escrow to provide additional collateral on the bad debts, and ask the IMF and World Bank to provide loans to increase collateral even more. In regards to debt restructuring and partial forgiveness, it seems that negotiating with the private parties that defaulted on home loans would be more likely to result in repayment than negotiating with financial institutions that have aggregated the loans, although the transaction costs would be much higher. If restructuring is only negotiated between large financial institutions, it seems overly optimistic to assume that they will be effective in collecting full payments on defaulted loans until either the housing market picks up and foreclosed houses can be resold, or private parties increase their ability to make payments. With the macro-economic context of falling income and increased household commodity prices (energy and food), it seems unlikely the ability of private parties to make payments will improve without restructuring the terms of their payments or giving them budget counseling that could change their spending habits. Perhaps the restructuring can be negotiated both at the scale of financial institutions to provide rapid bailout with low transaction costs, and at the scale of households to ensure realistic repayment terms. 4. Policy recommendations Some form of large financial bailout that either purchases bad debt or invests in its securities to increase the value of the debt will help address the crisis in the short-term. If the bailout is tied to market reforms, it could also help prevent reoccurrence of this situation. Increasing the value of the bad debt by investing into collateral may leverage greater market value than the US bailout package that purchases bad loans outright. Its seems unlikely that merely renegotiating debt with financial institutions will result in higher chances of debt repayments, and renegotiating debt on the household level at which it is ultimately owed should be an explicit component of an solution strategy. The transaction cost of restructuring bad debt at the household level is high, but could be distributed among financial institutions receiving the bailout, or some of the bailout money could be invested into those transaction costs rather than securities. The above strategies target financial institutions in wealthy countries rather than developing countries. While the well-being of international financial markets impact developing countries in a variety of ways, developing countries will not be the primary beneficiaries of a bailout, and trickle-down effects will be limited. If a primary concern is to ensure developing countries are not adversely affected, more direct interventions need to be considered. While the international financial markets are being sorted out, developing economies may experience shocks that could significantly set back poverty reduction. Direct interventions aimed at reducing short-term shocks could be a cost-effective complement to bailing out the financial sectors. For example, the IMF or World Bank could set up a temporary emergency investment fund for developing country financial markets to fill the gap of foreign investment that is being withdrawn. If the markets are truly sound, then lending money to them on a case-by-case basis until foreign investors calm down could be a fiscally conservative way of greatly reducing the shock. Many countries with significant foreign debt will have fiscal difficulties if exports fall, floating interest rates rise, or if their currency is pegged to the falling US dollar. The International Financial Institutes should monitor the magnitude of these stresses on nations that owe them money, and consider temporarily softening the stress of debt repayments until the other stresses subside. If exports fall and indebted countries have trouble meeting payments in foreign currency, the IFI’s could accept a portion of the loan payments in local currency, which could then be reinvested in the country. This could help reinforce financial markets suffering from the withdrawal of foreign investment, and could have the beneficial side effects of boosting that developing economy which would help Millennium Development poverty alleviation goals. This stream of local currency could provide greater leveral for poverty reduction if it was preferentially directed into local markets that that supply core services pursuant to Millennium Development Goals such as water, food, housing, or public health services. References 1. IMF, Financial Crisis Weighs on Global Economy, Sept 17, 2008 http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2008/NEW091708A.htm 2. New York Times September 24, 2008, Upheaval on Wall St. Stirs Anger in the U.N. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/24/world/24nations.html?_r=1&oref=slogin&pagewanted=print 3. BBC News, Central banks cut interest rates, Oct 8, 2008. http://newsvote.bbc.co.uk/mpapps/pagetools/print/news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7658958.stm 4. BBC News, Global response to rate cuts, Oct 8, 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7659679.stm 5. BBC News, Credit crisis: World in turmoil, Oct 8, 2008. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7654647.stm 6. The Brady Plan. EMTA. Downloaded Oct 6, 2008. http://www.emta.org/emarkets/brady.html History of brady bonds written by an financial community trade association formed “in response to … new trading opportunities … under the Brady Plan.” 7. BULGARIAN BRADY BONDS AND THE EXTERNAL DEBT SWAP OF BULGARIA. Armenuhi Pirian, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, University of Sofia, Bulgaria. Available online at: http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/NISPAcee/UNPAN009285.pdf 8. S.Y. Lee, M.E. Venezia. A Primer on Brady Bonds. March 9, 2000. Available online at: http://www.people.hbs.edu/besty/projfinportal/SSB%20Brady%20Primer.pdf 9. HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT. EMTA. Downloaded Oct 6, 2008. http://www.emta.org/emarkets/emarketsmainframe.html