The Supreme Court Raised Its Voice: Are The Lower Courts Getting

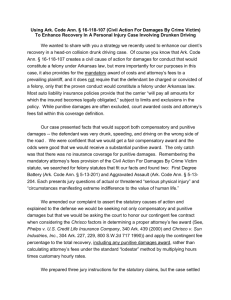

advertisement