ask first and tell later

advertisement

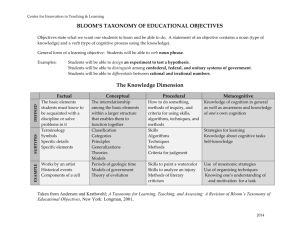

ASK FIRST AND TELL LATER: DEVELOPING CRITICAL THINKING BY DESIGN JACQUELINE A. MERZ The George Washington University jmerz@gwu.edu “So, what is the question?” is the query educators should ask themselves during course development. Much time is spent preparing lectures and power point presentations that rehash class reading assignments. Frequently little time is devoted to designing questions that facilitate the goal of developing student critical thinking like that of professionals in our fields. Through Bloom’s Taxonomy of cognitive objectives educators can construct hierarchical questions to attain course goals and enhance learning outcome. The following describes the use of questioning through Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives in the cognitive domain as discussed and practiced during a 50 minute workshop at the 2006 International SUN Conference on Teaching and Learning at the University of Texas, El Paso. Educators use a repertoire of teaching methods in their courses. However, the method that predominates in many classrooms in higher education is the standard lecture interspersed with occasional questions from the educator or student. My primary teaching and learning method in graduate courses usually begins with questions that roll into discussion and finally mini-lectures, hence, my “ask first and tell later” strategy. I find this method quickly engages the learner in course content, draws the learner into active participation, and appropriately directs students beyond basic recall to critical reflection and meaningful learning. The use of questions and class discussions are the tools of the trade for many of us who prefer to be recognized as a “facilitator” of learning, that is, one who guides learners from the initial stages of comprehending course content to reflection and ultimately critical thinking on its application in the field of practice. Bloom’s Taxonomy Developing critical thinkers is a goal of education. Educators can facilitate that goal by turning typical course objective statements into well designed questions to be used as an in-class teaching strategy, rather than only for course assignments or tests. Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives in the cognitive domain (Bloom, Engelhart, Furst, Hill, & Krathwohl, 1956; Krathwohl, Bloom, & Masia,1965; Anderson & Sosniak, 1994) is a well known scheme used by educators to develop course objectives. Briefly, the six levels of learning objectives from lowest to most complex are: 1) knowledge (remembering facts); 2) comprehension (understanding meaning); 3) application (using learning in new applications); 4) analysis (breaking the whole into parts for understanding); 5) synthesis (creating a whole from parts); and 6) evaluation (determining worth based on criteria). While knowledge (level 1) questions are 1 used extensively in the classroom to assess learner recall, the last three levels, that is, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation, promote critical thinking. Workshop participants practiced developing questions through Bloom’s Taxonomy and affirmed that this method requires practice, especially in Bloom’s levels 4, 5, and 6. Perhaps the difficulty lies in our tendency to most often use the first three levels of Bloom (knowledge, comprehension, and application) in course objectives and for course assignments and exams. However, the latter three levels, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation levels are more demanding and require critical thought. (See the Appendix, pp. 5-9 for worksheets, directions, and references distributed during the workshop. Refer to Brown 2001 in Selected Workshop References, p. 9 of which a section was used for the workshop exercise.) Asking Good Questions Questioning serves many purposes. Firstly, questions help the educator assess student recall and comprehension of course content. Although this technique is often used in written tests, it is also an excellent verbal teaching and learning strategy. Secondly, questions can extend thinking beyond simple recall (what is…?) to applying learning in various situations, making assumptions and discriminately analyzing concepts. Thirdly, questions help synthesize new learning with previous experiences to solve problems or identify potential problems and make informed judgments and decisions through critical thinking. Good questions should promote learner reflection and active learning, be prepared in advance rather than impromptu, and focus on the objectives and primary content of the session (Sanders, 1990). A method of good questioning includes: clearly stating the question (Sanders, 1990); allowing “wait time” (Duell, 1994) for the answer; and stressing the correct response (Sanders, 1990). Two additional elements in questioning protocol are: using probing questions to help support or clarify a response, or expand thinking; and calling on learners by name to reply to the question (Sanders, 1990). With the practice of naming a student to reply, the students are more likely “to try to formulate an answer” (Sanders, 1990, p. 122) in the event that they may be selected to respond. Although this approach may motivate the learner to prepare for the session, it has been my experience in graduate courses that unless a student appears to want to respond, calling on a student by name may put the learner ill at ease which can potentially create an apprehension that negates both the enjoyment of learning and maintenance of a safe learning environment. Although I am comfortable waiting nearly a minute for graduate students to ponder before offering a meaningful response to a tough question, Sanders (1990) notes “fifteen seconds may seem like an eternity to the inexperienced instructor” (pp. 121-122). However, “pause” (Sanders, 1990) or “wait time” (Duell, 1994) is essential for the learner to reflect on what is asked and draw from experiences to intelligently respond. Sanders (1990) suggests that student non-verbal feedback may provide an indication for the length of time to pause, but Duell (1994) reports apparently conflicting findings: …no evidence could be found that extended wait time enhances either low-level or higher level achievement. In fact, extending it from 3 s [seconds] to 6 s [seconds] led to a significant decrease in higher level achievement. No matter 2 how logical or satisfying it might be to believe that giving a student more thinking time before they begin their answers to questions, these experiments found no evidence to support the hypothesis that just extending wait time for university students will enhance higher level achievements (p. 412). Duell (1994, p. 412) does caution about generalizing his findings to “typical university classrooms” (students who volunteered for the study were awarded course points). Based on my years of teaching experience, I have found that some reasonable amount of time is required for a student to respond to a question, despite the discomfort or awkwardness that silence may be for the instructor. The exact length of time to wait depends on many variables such as, student motivation, degree of student preparation for a session, and difficulty of the question. Repeating the answer offered by one student will often encourage responses from other students who may offer a different perspective or embellish the initial response which, in turn, often opens meaningful discussions between learners-professor and learners-learners. Regardless of the number of responses, facilitators must provide feedback to acknowledge that each response was heard, reinforce the accurate responses and correct misunderstandings. Additionally, writing both the question and student responses on a visual (whiteboard or overhead transparency) is a good method to eliminate student time to recall the question and more time to think about the answer, and visually acknowledges student responses. The difficulty lies in what level of questions to ask and when to ask them. To a great extent these issues can be addressed during course design. Course Design and Questions through Bloom After developing course objectives through Bloom’s Taxonomy, various teaching and learning strategies are selected to help accomplish each objective in Bloom’s cognitive domain. Strategies for knowledge (level 1) may include lectures and movies, and for comprehension (level 2) objectives student presentations and discussions can be used. Simulations and student projects are appropriate for application (level 3) objectives. Problem-based scenarios and case studies address levels 4 and 5, analysis and synthesis respectively. Exercises that require making judgments based on criteria are appropriate for level 6, evaluation. (Refer to United States Department of Agriculture for a comprehensive list of instructional strategies.) Prior to each class session, questions should be carefully prepared to stimulate student thinking for each learning objective planned for the session. The level of question in Bloom’s Taxonomy, that is, lower or higher order, will depend on the educator’s purpose. For example, level 1 questions may ask students to recall, or for level 2 explain, the discussion from a previous session or the assignment the student prepared for the current session. Although a typical sequence of questions may start at level 1 and move up the hierarchy, I most often begin the questioning with a level 3 (application) question or higher order questions. For example, I may open the initial course session in my graduate learning theory course by asking “how might you apply from what you learn in this course to your practice as a professional?” or “what do you want to learn from this course for your professional development?” These questions are attempts to make initial connections between classroom learning and professional practice and set the stage for a case study or problem-based scenario planned for a future session. 3 The large group format may then change to small groups to discuss “what is learning?” Although this may appear to be a typical question of recall based on assigned readings to prepare for the session, students may also compare their past experiences with the assigned readings to develop a definition of learning. After discussion of the replies from the small groups, I may provide a short recap of the reading assigned for the session followed by “how does your definition of learning compare to the definition presented by……or the theory of…?” This comparison question moves students into analysis, level 4 of Bloom’s hierarchy. Following responses to my question from individuals or small groups, I may begin a mini-lecture to extend student thinking and/or correct misinterpretations. Hence, the “ask first and tell later” strategy serves several purposes. It extends thinking beyond recall, moves in and out of various levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy, stimulates critical thinking, and provides me with an assessment of what is understood and where to begin the telling lecture. This process continues throughout the course and culminates in a final exercise, a problem-based scenario or case study for which all the levels of Bloom are addressed. An important requirement in my courses is to maintain a safe learning environment, one that does not permit personal criticism and opens the door to free exchange. Students can be tasked to establish ground rules to permit expression of ideas, support collegial discussion, and assist in classroom management during interactions Questions that require thinking beyond mere recall, collaborative learning through open discussion, meaningful feedback, and a safe environment can easily be planned when designing a course and have proven to be very effective methods of teaching and learning in my courses. Although this may be a change for those who predominately lecture, I highly recommend experimenting with the “ask first and tell later” strategy to actively engage learners with course content and better develop our students to think like professionals in our fields. References Anderson, L. W. & Sosniak, L. A. (Eds.). (1994). Bloom’s taxonomy. A forty-year retrospective (Ninety-third yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education. Part II, pp.927). Chicago: The National Society for the Study of Education. Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay. Duell, O. K. (1994, Summer). Extended wait time and university student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 31(2), 397-414. Krathwohl, D. M, Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1965, reprinted). Taxonomy of educational objectives. The classification of education goals. Handbook II: Affective domain (pp. 186-193). New York: David McKay Company. Sanders, R. E. (1990). The art of questioning. In Galbraith, M. W. (Ed). Adult learning methods (pp. 119-129). Malabar, FL: Krieger. United States Department of Agriculture. Natural Resources Conservation Service. National Employee Development Center. Instructional Systems Design (ISD), Specifying instructional strategies. Bloom’s Taxonomy. Retrieved on February 18, 2006 from: http://www.nedc.nrcs.usda.gov/isd/isd8.html 4 Appendix: Workshop Materials Ask First and Tell Later: developing critical thinking by design Dr. Jacqueline Merz The George Washington University “So, what is the question?” is the query educators should ask themselves during course development. Much time is spent preparing lectures and power point presentations that rehash class reading assignments. Frequently little time is devoted to designing questions that facilitate the goal of developing student critical thinking like that of professionals in our fields. Through Bloom’s Taxonomy of cognitive objectives, working groups will practice a method of hierarchical question construction for use throughout their courses. Learning Objectives: Given a brief reading assignment for content of question construction and a summary of Bloom’s Taxonomy of cognitive objectives, participants will be able to: 1. Develop at least one question for each of the six primary levels in the cognitive domain of Bloom’s Taxonomy. 2. Argue when higher-level questions might be posed within a course to be most effective for different student levels of experience. 3. Assess various learning formats and teaching strategies when higher-level questions would be most appropriate in assisting in the development of student critical thinking as observed in our fields. Workshop Outline 10 minutes Workshop purpose and overview Discuss Bloom’s Taxonomy of cognitive objectives and distribute session materials 20 minutes Scenario: Your department decided that the foundational course you teach will include group projects to better prepare students for their aspired profession, and/or enrich the learning required in their current profession to work in groups, e.g. committees, projects, work processes. You assign the reading you have in hand to your class and design questions aligned with the 6 levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy of cognitive objectives to facilitate a class discussion on the reading. Directions: Break into working groups of 4-6 individuals. Each group should be composed of educators in the same or related discipline if possible. Read the article provided As a group, construct one question for each of the 6 levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy to address your class discussion on “groups” based on the scenario above. Post the group questions for discussion. 15 minutes (all participants convene to large group) A spokesperson for each group presents their group’s questions for discussion Complete objectives 2 & 3 above 5 minutes – Q & A 5 Worksheet Bloom’s Taxonomy of Cognitive Objectives Levels: 1. Knowledge, 2. Comprehension, 3. Application, 4. Analysis, 5. Synthesis, 6. Evaluation Lowest Highest Degree of difficulty Directions: Using the reading as context, develop one question in each level of the taxonomy, and if the group composition permits, include in your questions if possible relevance to your discipline. Level 1. Knowledge remembering facts Associated Verbs define discuss identify label list name outline quote recall recite restate summarize Sample Question Leaders….. Who are………… What is………… Where did….…… When………….. How many……….. Your questions related to the reading: Level 2. Comprehension understanding meaning Associated Verbs Sample Question Leaders….. associate describe elaborate estimate explain identify How might one go about…… What is the meaning of……… Why do you think………….. In your own words, explain…… Can you provide examples…….. interpret modify outline paraphrase relate predict Your questions related to the reading: 6 Level 3. Application using learning in new situations Associated Verbs Sample Question Leaders….. build compute construct demonstrate employ illustrate How might this apply in…. How would you use this method to… Given…what would happen if…. What other way can you use…. If you were…how would you….. model operate practice represent show solve Your questions related to the reading: Level 4. Analysis breaking the whole into parts for understanding Associated Verbs categorize conclude contrast debate diagram distinguish discriminate examine infer order separate question Your questions related to the reading: 7 Sample Question Leaders….. What is the relationship between…. How would you classify………… How does this compare to……. Based on what assumptions……. What evidence supports………. Level Associated Verbs Sample Question Leaders….. assemble compile combine create design develop How would you…to include…. What other methods………….. What solutions would you…….. What could be done to modify….. How would you design a different… 5. Synthesis creating a whole from parts generate invent organize plan propose rebuild Your questions related to the reading: Level 6. Evaluation determining worth based on criteria Associated Verbs Sample Question Leaders….. appraise assess critique determine estimate grade What would be the first priority…. How would you justify………….. What is the significance of………… To what extent do you think….. How effective was …………… judge rate rank score support value Your questions related to the reading: 8 Ask First and Tell Later: developing critical thinking by design Selected Workshop References Anderson, L. W. & Sosniak, L. A. (Eds.). (1994). Bloom’s taxonomy. A forty-year retrospective (Ninety-third yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education. Part II). Chicago: The National Society for the Study of Education. Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay. Brown, B. L. (2001). Group effectiveness in the classroom and workplace. ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education. Practice Application Brief no.15. Retrieved on February 11, 2006 from: http://www.cete.org/acve/docs/pab00024 Clark, D. (1999; 2001). Learning domains or Bloom’s Taxonomy. Retrieved on January 1, 2006 from: http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html Exploration in learning & instruction: the theory into practice database. Retrieved on January 5, 2006 from: http://tip.psychology.org/taxonomy.html Fowler, B. (Contributor). (1996). Critical thinking across the curriculum. Bloom’s taxonomy and critical thinking. Longview Community College. Retrieved on January 20, 2006 from: http://www.kcmetro.cc.mo.us/longview/ctac/blooms.htm Krathwohl, D. M, Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1965, reprinted). Taxonomy of educational objectives. The classification of education goals. Handbook II: Affective domain (pp. 186-193). New York: David McKay Company. Sanders, R. E. (1990). The art of questioning. In Galbraith, M. W. (Ed). Adult learning methods (pp. 119-129). Malabar, FL: Krieger. Types of questions based on Bloom’s taxonomy. From Bloom, et al. 1956. Retrieved on January 15, 2006 from: http://www.honolulu.hawaii.edu/intranet/committees/FacDevCom/guidebk/teachtip/quest ype.htm 9