2. The Potentials of Tethered Flight Technology

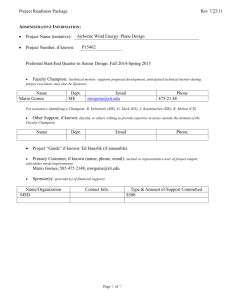

advertisement