Introduction - Louisiana State University

advertisement

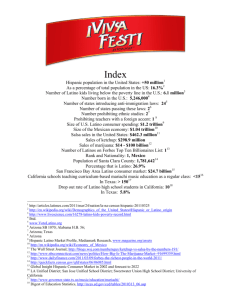

Latino Representation and Education: Pathways to Latino Student Performance Ashley D. Ross Ph.D. Candidate Department of Political Science Texas A&M University aross@politics.tamu.edu Stella M. Rouse Assistant Professor Department of Government and Politics University of Maryland srouse@gvpt.umd.edu Kathleen A. Bratton Associate Professor Department of Political Science Louisiana State University bratton@lsu.edu Abstract: The rapid growth of the Latino population over the past fifteen years has led to a significant increase in levels of primary and secondary school enrollment rates of Latino children. Research on Latino education has demonstrated the institutional and contextual challenges faced by this increasingly significant group, but studies that link Latino representation and Latino educational performance have neglected to empirically sort out the direct and indirect effects of representation on student achievement. The central assumption in these studies outlines a casual chain running from Latino political representation—school boards—to Latino bureaucratic representation—administrators and teachers—to Latino student performance. This study tests these theoretical assumptions by employing a path analytic model using data from 1040 Texas school districts for the years 1997-2001 to tease out the direct and indirect effects of Latino representation on Latino student achievement. We find robust evidence of the impact of Latino representation on Latino educational attainment, operating via a direct effect on the number of Latino administrators and teachers and an indirect effect on Latino student performance. Additionally, our results demonstrate that descriptive representation becomes substantive representation in the area of education policy for Latinos and that this relationship remains strong over time. These findings underscore the importance of school board elections and school district hiring practice on Latino student performance. 1 Latinos are the largest and fastest growing minority group in the U.S., particularly among children—those who have the most at stake in the education system (U.S. Census Bureau 2000; Llagas 2003). 1 As illustrated by Figure 1, the rapid growth in the number of Latinos has resulted in a rise in Latino enrollment at elementary and secondary schools across the nation, while during the same period, enrollment rates have decreased for whites and have remained stagnant for blacks. [Figure 1 about here] At the same time, the challenges faced by Latino students in education have been well-documented. The national drop-out rate for Latino students is substantially higher than for others, and Latino students score substantially lower than Anglo students on standardized tests (National Center for Education Statistics 2002). Moreover, Latino students are more likely than other students to face challenges related to immigration (Darder, Torres, and Gutierrez 1997; Gibson 2002); most students who are classified as “limited English proficient” are Latino (Riley and Pompa 1998). Not surprisingly, the question of Latino student achievement has attracted considerable scholarly attention in the last two decades. Much of the scholarly interest in the educational outcomes of Latino students draws on research in the fields of education, policy, and public administration (e.g. Bali and Alvarez 2004; Smith and Larimer 2004; Steele 1997). However, because of the role that elected officials play in crafting education policy, the extant scholarship also draws upon theories of political representation, and specifically focuses on the potential connection between descriptive and substantive representation. In descriptive representation, "The representative does not act for others; he 'stands for' them, by virtue of a correspondence or connection between them, a resemblance or reflection" (1967, p. 61). The core of political representation, however, is substantive: "representing here means acting in the interest of the represented, in a manner responsive to them" (1967, p. 209). Though Pitkin herself Most scholarly work that references people of Spanish origin use the terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably. For purposes of uniformity we use the term “Latino” in this paper. 1 2 emphasizes the distinction between the two forms of representation, her work has served as the foundation of rich literature that examines the potential connection between the two, particularly with respect to the representation of women and minorities. As Hicklin and Meier observe, "Theory leads us to expect that, in most situations, any increase in minority representation will result in real policy gains for minority groups" (2008, p. 852). Despite the apparent intuitive appeal of the potential link between descriptive and substantive representation, the findings of a broad set of empirical studies are quite mixed. The research taken as a whole suggests that the strength of the link between descriptive and substantive representation depends on several contextual factors. Meier (1993a) contends that substantive representation is achieved when (1) the demographic characteristic is highly salient, such as race; (2) representatives have the discretion to act; and (3) policy decisions are directly relevant to the descriptive characteristic. Other scholars place a similar emphasis on both the salience of the policy in question, and the control that legislators have over the policy. Bratton and Ray (2002), for example, argue that descriptive representation matters most significantly when policies are first being developed—that is, when elected officials have the most control over policy development. Haynie (2000) and Preuhs (2007) argue that for descriptive representation to translate into substantive representation, not only the overall legislative body but also the set of relatively powerful legislators must be descriptively representative. Prior research has focused on the connection between descriptive representation on school boards and substantive representation of the interests of constituents, in the form of student performance. But does education policy meet the conditions for the translation of descriptive into substantive representation, described above? Ethnicity and race are salient characteristics, given the well-documented ethnic and racial differences in educational performance. The educational performance of Latino students is clearly of interest to Latino constituents. Indeed, the link between representative and constituency may be even more evident local representative institutions than in state or national representative politics. 3 The one missing piece of the puzzle is discretion of the policy maker over relevant policy. School boards are relatively small, and have direct control over education policy.2 Nonetheless, as Meier and England (1984) note, it is difficult for school boards to influence test scores and other measures of educational performance, at least in the short-run. Given that school board members are relatively far removed from the classroom in which performance is measured, what is the mechanism by which descriptive representation influences educational outcomes? Ours is the first contemporary effort to take a comprehensive approach to this question, explicitly recognizing that the link between school boards and test scores is substantively important – but indirect. Specifically, we model the indirect effect of political representation on educational outcomes for Latino students, operating through the direct effects of school board composition on administrators, teachers, and resources. Moreover, our general finding that minority representation matters for policy outcomes that are relevant to minority citizens has broad implications for local and state governing bodies in policy areas beyond education. The first section of the paper outlines the literature on Latino representation and Latino student performance. The concept of representation is discussed and past findings regarding the link between Latino representation and Latino educational outcomes are highlighted. The second section builds an argument for presenting a path analytic model as a way to interpret concepts of representation and to understand the effects of both political and bureaucratic factors on Latino education. In section three we present the data and specify the models to be analyzed. Results of the structural equation model are examined in section four. In the last section we discuss conclusions of our analysis and offer some suggestions for future research on Latino education using this type of modeling. Previous Literature 2 Scholars have, of course, debated whether school boards effectively control education policy. Chubb and Moe (1990) argue that as democratic institutions facing a multitude of competing demands, school boards are rendered ineffective in their attempts to respond to demands for quality. Smith and Meier (1994) and Meier, Polinard and Wrinkle (2000) argue that school bureaucracies grow in response to poor student performance, and that bureaucracies respond by reducing class sizes and increasing staff. 4 Latino representation has been widely studied, from city councils (Shockley 1974) to national and state legislatures (Bratton 2006; Hicklin and Meier 2008; Kerr and Miller 1997) to school boards (Meier and Stewart 1991). These works generally show that ethnic diversity in representation is associated with the substantive representation of interests on issues that are relatively salient to Latino citizens.3 For example, Bratton (2006) found that Latino representatives were more likely than their colleagues to focus on issues related to bilingual education and immigration. Using Southwest Voter Research Initiative Scores, Kerr and Miller (1997) found that Latino members of the U.S. House were supportive of the interests of Latino citizens. A number of prior studies demonstrate a relationship between racial or ethnic diversity on school boards and policy outcomes. Much of the early research focused on the relationship between the representation of African Americans and educational outcomes for African American students. Using data from urban school districts in the 1970s, Meier and England (1984) found that a higher number of African Americans on a school board was associated with a variety of positive educational outcomes, including higher retention and lower suspension rates for African American students, a higher number of African-Americans in gifted classes, and a lower number of African-Americans in special education classes. Using a survey of a national sample of large school districts, Stewart, England, and Meier (1989) found that the proportion of members of the school board who were African American was significantly associated with the proportion of school administrators who were African-American, even after taking into account the proportion of African Americans in the district population. Likewise, racial composition of school administrative staff was related to the racial composition of teaching staff. However, racial diversity on the school board was not significantly associated with racial diversity among teachers. The authors observe that this combination of findings is not surprising, given that school Descriptive representation is often referred to as “passive representation” and substantive representation is also labeled as “active representation” in the Latino education literature (Meier and Stewart 1991; Meier and O’Toole 2006). 3 5 boards can support efforts to recruit or promote black administrators, while at the same time respecting the norm that they should not be involved in hiring teaching staff (p. 299-300).4 Similar studies on Latino representation and educational outcomes suggest (but generally do not directly test) that the connection between descriptive representation on school boards and substantive educational outcomes is largely indirect. Using data from the late 1970s, Fraga, Meier, and England (1986) found that the proportion of school board members who were Latino was significantly and positively associated with higher numbers of Latino teachers. And while Latino school board representation was not linked to Latino student performance, Latino teachers were correlated with lower dropout and higher graduation rates of Latino students. Similarly, Meier and Stewart (1991) found that Latino school board members were related to greater numbers of Latino school administrators, which in turn was associated with higher numbers of Latino teachers, which in turn was associated with positive educational outcomes for students. In a study of twelve Florida school districts in the 1980s, Meier (1993b) found that ethnic diversity among teachers was much more important than ethnic diversity among principals in determining positive outcomes for Latino students. More recent research has generally confirmed these paths. Using a survey of school districts conducted in 2000, Leal, Martinez-Ebers, and Meier (2004) find the same basic pattern as previous analyses: more Latino school board members were positively associated with more Latino school administrators, and more Latino school administrators were related to more Latino teachers, particularly in majority-Latino districts. Using data gathered from Texas school districts, Meier et al (2005) find that greater ethnic and racial diversity in school boards elected based on wards contributes to more diversity among administrators and teachers. One of the few studies that distinguishes between direct and indirect effects produced somewhat mixed findings. In a study of 64 Texas school districts from 1976 through 1986, Polinard, Wrinkle, and Longoria (1990) find that Latino school board representation directly influences the proportion of Latino school administrators, the proportion of Latino school administrators in turn directly influences the 4 See also Meier, Stewart, and England (1991). 6 proportion of Latino teachers. Moreover, the total effect of school board representation on the proportion of Latino teachers is enhanced by a small but significant direct effect of school board representation on the proportion of Latino teachers. However, they find much weaker evidence of a link between the proportion of Latino teachers and educational outcomes; while (as expected) a higher percentage of Latino teachers was associated with the assignment of fewer Latino students to bilingual programs, the proportion of Latino teachers was actually associated with higher suspension rates for Latino students. We contribute to prior knowledge by providing the first contemporary analysis to trace the full path from descriptive representation on school boards (in this case, the proportion of Latinos elected to the board) to substantive educational outcomes (in this case, test passage rates). We argue that the link between school board representation and substantive outcomes is primarily indirect: school boards influence administrators, administrators influence teachers, and teachers influence educational outcomes. Distinguishing between the direct and indirect effect of descriptive representation is crucial, because it helps us answer assess the link between descriptive representation and substantive representation in a context where elected officials do not have direct and immediate control over policy-making. We note in particular that we incorporate all four stages of the process into our path model: school boards, administrators, teachers, and students. In general, the last step in this pathway from descriptive representation to substantive outcomes—the link between teachers and student performance— is the least examined in the prior literature. Several recent studies (e.g., Leal, Martinez-Ebers, and Meier 2004; Meier et. al. 2005) focus primarily on the relationships among diversity on school boards, and diversity among administrators and among teachers. Yet the earlier literature was not entirely conclusive regarding the influence of teachers on student outcomes; Polinard, Wrinkle, and Longoria, for example, found (1990) mixed and relatively weak effects of Latino teachers on Latino student performance. Student performance represents the most "substantive" of interests considered; without changes in actual educational outcomes, the representation of Latinos on school boards, among administrators, and among teachers can be seen as largely symbolic. It is therefore a crucial part of our analysis. 7 In the following section, we outline a path model linking descriptive representation to substantive outcomes. Model Development: Mapping the Causal Links that Affect Latino Education As discussed above, research on the determinants of Latino education policy focuses primarily on political and bureaucratic representation. There is a general assumption in the literature of a “top-down” process, whereby political factors affect bureaucratic elements, which in turn influence policy outcomes and educational performance (Meier, Juenke, Wrinkle, and Polinard 2005). Researchers often make implicit assertions about the relationship among variables within this process. However, empirical analyses usually segregate political and bureaucratic variables (see Polinard et al. 1990 and Meier and O’Toole 2006 as exceptions), or test as direct effects what are likely indirect effects of one variable upon another (i.e. school board influence on student achievement). These implicit assertions often occur with little analysis or discussion about how variables in the entire process may interact with one another. Even though regression estimates can show the significant (or insignificant) effects of certain independent variables upon dependent variables, less is surmised about the causal relationships of these measures. In Figure 2 we present a conceptual model to examine the causal connections between political, bureaucratic, and performance variables that are hypothesized to affect Latino educational attainment. We argue that, consistent with the concepts of representation, the “top” point in the path analytic model is Latino political representation, as measured by school board composition. We expect that school districts with a higher percentage of Latino students will have more Latinos on school boards, as maintained by the concept of descriptive representation. In turn, we expect that school boards with more Latino school board members will also positively affect the number of Latino administrators and Latino teachers in a district. Further, in line with the theory of representative bureaucracy, which according to Meier and O’Toole, is a theory “that considers such questions as when minority bureaucrats are likely to act in ways that benefit minority citizens” (2006: 180), we argue that Latino administrators should also have a positive effect on the number of Latino teachers in a district; and that Latino teachers, themselves acting 8 as “street level bureaucrats” (Lipsky 1980), will improve the educational attainment of Latinos (Meier, Wrinkle, and Polinard 1999). In short, descriptive representation will lead to substantive representation. Of course, school districts have similar incentives and punishments for student performance, and, therefore, school board representatives, administrators, and teachers should equally promote the academic achievement of all students regardless of race. Yet a great deal of prior research has shown that race, ethnicity, and social class are salient factors in educational outcomes. Iin the first two steps of our path model (school board representation influences on administrators, administrative representation influence on teachers), there may be a universal commitment to positive educational outcomes—but Latino school board members and administrators may be more likely to identify the recruitment of a diverse set of administrators and teachers as important—and may be more effective in those recruiting efforts. With respect to the last step of our path model (teacher influence over student performance), teachers clearly have an incentive to do what they can to improve test scores. At the same time, research indicates that at least some portion of the ethnic, racial, and sex gap in test scores can be attributed to "stereotype threat"—that children perform less well on exams when they are concerned about confirming what they know to be negative cultural stereotypes about their intellectual and academic abilities (Steele and Aronson 1995). Group composition—and presumably the race, ethnicity, or gender of the teacher— can serve to contradict those negative stereotypes, and mitigate self-doubt, thus improving educational performance. We also assert that the number of Latino students in a district influences variables throughout the model. We have previously mentioned the hypothesized effect of Latino students on school board composition. In addition, we expect that an increase in the number of Latino students will have a positive influence on the number of Latino school administrators and Latino teachers. Similarly, an increase in Latino students should also increase the amount of expenditures per student, and positively influence Latino educational achievement. A rise in the number of Latino students should also cause an increase in the overall number of low income students, since poverty is a major issue in the Latino community 9 (Stokes 2003). In turn, we expect that an increase in the number of low income students will negatively impact overall student achievement. The effect of Latino students on teacher experience is theoretically unclear. One argument is that an increase in Latino students will lead to more experienced teachers, since it is experienced teachers who are better equipped at tackling the wide Latino achievement gap. On the other hand, many experienced teachers are unwilling to teach in high minority school districts because of a lack of resources. To test these theoretical expectations, we employ a structural equation model using various measures, which are discussed in the following section. [Figure 2 about here] Data and Methods Our path analysis includes 1,044 public school districts in Texas for the years 1997-2001. The data used in this study come from a larger data set collected by Dr. Ken Meier of Texas A&M University, “The Texas Minority Education Study, Project for Equity, Representation, and Governance” (2005). The data set was compiled using information obtained primarily from the Texas Education Agency and supplemented with an original survey, as well as other supporting data sources.5 Texas is chosen as the sample for this research because it is a heterogeneous state with diverse school districts (Meier and O’Toole 2006). Texas also has a large Latino population dispersed throughout the state, which makes it a good test case for exploring the determinants of Latino student performance. And while the majority of Latinos in Texas are of Mexican heritage, so are most Latinos in the United States. The Latino and The only variable included in this data set not directly obtained from the Texas Education Agency is the “percent Latinos on school boards” (school board ethnicity) measure. This variable was created using government Census data of school boards, information from the Texas Association of School Boards and annual compilations of the National Association of Latino Elected Officials (NALEO). The data was also supplemented by phone surveys. For more details on how this variable was constructed, see Meier and O’Toole 2006 (appendix). 5 10 general population of Texas mirrors the rest of the country in terms of racial diversity, which makes the findings of this study generalizable to many contexts across the United States.6 The data for this study include a variety of political, bureaucratic, and achievement measures that are commonly recognized in the literature as potential influences on Latino student performance. Descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study can be found in Appendix A. To estimate the effects of Latino representation on the educational achievement of Latino students, we focus on one specific measure of performance—standardized test scores. Educational attainment of Latino students and students in general is measured in our model as the percentage of students that pass the TAAS (Texas Assessment of Academic Skills). This test is given to children every year from grades 3 to 8, and is a requirement for high school graduation (Slobogin 2001). Although there are other measures of achievement, passage rates for the TAAS provide a good way to gauge educational attainment throughout the careers of students. The average Latino pass rate in Texas school districts for the years 1997-2001 is 73% while 86% of White students passed, according to our data. TAAS pass rates is a suitable as a measure of substantive representation because it not only measures Latino educational attainment but also Latino preferences. Overall, Latinos value education— 95% of Latino parents say that it is “very important” for their children to go to college compared to 78% of White parents that say the same (PEW 2004). And six of ten Latinos consider standardized tests like the TAAS to be unbiased indicators of educational attainment (PEW 2004). Therefore, TAAS pass rates adequately measure substantive representation from the perspective of educational outcomes resulting from the preferences of Latinos and the subsequent actions of Latino representatives. Our first variable of interest is political representation, measured as the number of Latinos that serve on school boards. School boards, as the most basic units of representation, are involved in all areas of the district’s education system. Leal et al. state that school boards, “shoulder much of the 6 Scholars have observed that there may be resistance to knowledge gained through single-state studies. However, as Nicholson-Crotty and Meier (2002) observe, "the unique characteristics of a state may make it a particularly desirable venue in which to test a theory" (p. 414). They also note that data sets drawn from single states can enhance internal and construct validity, while still preserving the rich information levels of large sample sizes. 11 responsibility for the quality of public education in America” (2004: 1225). Consistent with minority representation theory and past studies (Fraga, Meier, and England 1986; Polinard, Wrinkle, and Longoria 1990; Meier and Stewart 1991), we expect Latino school board members to positively affect Latino representation on the administrative and teacher levels as descriptive representation develops into substantive representation. This measure is the percentage of Latinos on school boards as a total of all school board members in a district. The theory of representative bureaucracy suggests that minority administrators and teachers, who are at the “front lines” of implementing education policy, have a substantial effect on the academic performance of minority students (Hess and Leal 1997; Meier, Wrinkle, and Polinard 1999). We include two variables of bureaucratic representation in our model that capture the number of Latino administrators and the number of Latino teachers which are employed in each school district. These variables are measured as a percentage of total administrators, and as a percentage of total teachers, respectively. Literature on Latino education also finds that, not just the presence of minority teachers is needed to affect minority student attainment, but that teacher experience is also an important factor. Meier et al. say of teachers that they “are a crucial element in a student’s educational environment.” And that “as a profession based on lifelong learning, there should be some advantage to teachers with adequate experience…” (1999: 1029). Our model contains a variable that captures the average years of teacher experience. This variable should positively correlate with Latino student performance. Intuitively it makes sense that more money spent on education will lead to better educational outcomes. However, there is a debate in the literature about the tangible and direct benefits of monetary expenditures upon educational attainment in general. Studies conducted by Hanushek (1981, 1998) find a negative correlation between expenditures and achievement; while other research has shown positive, but minimal impact from expenditures (Figlio 1998; Wenglinsky 1997). Similarly, research on the effects of expenditures on minority and Latino student attainment has also produced mixed results, primarily finding mediating factors affecting a direct significant link between expenditures and achievement (Meier et al. 1999; Leal and Hess 2000; Meier and O’Toole 2006). Our conceptual model hypothesizes a 12 positive link between monetary resources, and both overall student achievement and Latino student achievement. Although there are different types of education expenditures, our variable, “per pupil spending”, consists only of per student expenditures for instructional purposes. As Meier and O’Toole (2006) argue, this may better tap into the direct impact of expenditures upon Latino student performance. We also include a poverty variable in our model. Meier et al. write that “poverty is a serious constraint on student performance” (1999: 1028). As previously mentioned, poverty disproportionately affects the Latino population. Over 27 percent of Latino children live in low-income homes, and Latino poverty has been linked to poor educational attainment (Brindis, Driscoll, Biggs, and Valderrama 2002). Poverty is measured as the percentage of students who are eligible for free or reduced lunches at school, and the variable is labeled “low income students”. In addition to the substantive variables that comprise the path analytic model, we also include five dummy variables for the years 1997 - 2001 to account for the fixed effects of time upon the main explanatory measures. We employ structural equation modeling (SEM) to test the linkages among our variables. This technique consists of a series of regression equations which are fitted simultaneously using maximum likelihood (ML) as the model estimator.7 Findings The statistical results from our path analysis are illustrated in Figure 3, which presents only the most theoretically interesting paths; the parameter estimates are presented in Appendix B8. In addition, Table 1 decomposes the path coefficients of our model into direct, indirect, and total effects. Overall, our model supports past work in this area. A clear “top-down” process is occurring as evidenced by the direct and indirect effects running from Latino political representation to bureaucratic representation to student performance. 7 Maximum Likelihood is the standard method of estimating free parameters in structural equation modeling (Hoyle and Panter 1995), and is appropriate over other regression estimators when there are missing variables, as is the case with our study. 8 Appendix B presents the structural equation model in a matrix format, illustrating the coefficient values for each pair of relevant variables in the regression analysis. 13 One significant issue in structural equation modeling is how well the model “fits” the data. The assumptions from “absolute fix” indexes (e.g. X2 goodness of fit test) are usually violated in SEM. Therefore, researchers rely on “adjunct” or “incremental fit” indices to test goodness of fit. One of the most common fit statistic used in Structural Equation Models is the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI)9 With the criterion for t this index ideally being above .95 (Hu and Bentler 1999), it appears that our model fits relatively well to the data (TLI = ..93)10. [Figure 3 about here] [Table 1 about here] First, note that the number of Latino students has a large impact on the number of Latino school board members, administrators, and teachers, as hypothesized above. Our findings indicate that the number of Latino students in a school district positively and significantly affects the number of Latino representatives on school boards (path coefficient = .622), the number of Latino administrators (path coefficient = .192), and the number of Latino teachers (path coefficient = .113). We also observe the statistically significant impact of Latino students on the percentage of low income students (path coefficient = .474), reflecting the higher rates of poverty found in Latino communities. Additionally, the percentage of Latino students positively impacts Latino student achievement (path coefficient = .017) but negatively influences overall student achievement (path coefficient = -.033). Finally, there is a statistically significant relationship between Latino students and the amount of instructional expenditures per student. This suggests that school districts in Texas allocate funds, at least in part, based on levels of the Latino student population. The pathway between Latino students and teacher experience is statistically insignificant. 9 For more information on fit criteria, see Hu and Bentler (1999). One factor driving down the TLI measure may be the inclusion of time fixed effects. We ran the model without the yearly dummy variables and the TLI is .99. 10 14 At the same time, it is important to note that substantive, the effect of the Latino student population works in opposite directions throughout the path model. Latino student population is positively correlated with Latino representation on school boards, and among teachers and administrators, and is directly associated with instructional spending and Latino student achievement. All this works to elevate Latino student achievement. However, the Latino student population is higher in less wealthy communities, and is negatively associated with overall student achievement, which in essence counteracts the other, more positive, effects. Therefore, the substantive effects of Latino student population on Latino student achievement appear to be quite small in magnitude. Second, the model supports the causal chain between political representation, bureaucratic representation, and students. Although the proportion of school board members that are Latino significantly influences the proportion of administrators that are Latino, the proportion of teachers that are Latino, and the TASS passage rates of Latino students, by far the most powerful influence exerted by the school board is over the ethnic composition of administrators. The association between school board composition and both ethnic diversity among teachers and passage rates of Latino students is primarily indirect, operating through their control over the administrative staff. Likewise, administrators have a strong direct effect over teachers, and virtually no direct effect on student scores. Teachers, acting in the role of “street level bureaucrats” have a significant and direct impact on Latino educational performance (path coefficient = .090). This effect is larger than the indirect effect of Latino school board representation on Latino student achievement (path coefficient = .053), suggesting that teachers play in the educational achievement of Latino students. However, here we offer an important caveat: we find that the relationship between the proportion of Latino teachers and Latino student achievement is relatively small in magnitude. Indeed, the total effect of Latino school board representation on Latino student achievement is of roughly the same magnitude as the total effect of the proportion of teachers that are Latino on Latino student achievement. We note as well that teacher experience seems to have a much more substantial overall influence on Latino student achievement than the presence of Latino teachers. The size of the relationship between 15 teachers and students may be because our measures are taken from districts overall. Given that education research indicates that some factors that influence test performance are very immediate and situationspecific, stronger effects might be observed if data were gathered directly from classrooms (or even more directly, from test sites). Our finding of a significant influence of the percentage of Latino teachers on the percentage of Latino students who pass TAAS is not a trivial finding, particularly given the difficulty that policy makers and practitioners have had in reducing test gaps. Nonetheless, it appears that the weakest link in the path between political representation and substantive outcomes appears at the end of the pathway, in direct influences on the substantive outcome in question (Latino student achievement.) Third, our results demonstrate the importance of district resources on educational performance. Per capita instructional spending significantly impacts both total student achievement and, even after controlling for total student achievement, Latino student achievement. Also, as expected, the relationship between low income students and overall student achievement is negative and significant (path coefficient = -.272). Considering this finding, in conjunction with the correlation between overall student achievement and Latino student achievement (path coefficient =1.081), it is clear that the resources of the district are crucial to the educational performance of all students. Unfortunately, as we pointed out above, minorities are often concentrated in low income districts; therefore, it is evident that districts exist with a high proportion of minority students, but without the resources to educate them. This lends further support to the well established impact of poverty on educational outcomes for minority students. In addition to financial resources, the findings highlight the importance of human resources— teachers. Teachers with more experience significantly impact overall student achievement and Latino student achievement. This result is different from Meier et al. (1999: 1030) who find teacher experience to have a positive effect on Anglo students and all students, but a negative effect on Latinos. Finally, we find that time (fixed effects) has an inconsistent impact on the main explanatory variables. Time is significant only for Latino student enrollment (Y99-Y01) and Latino school board members (Y98, Y00), indicating that Latino enrollment and hiring practices were distinct in these years. 16 In sum, the findings demonstrate descriptive representation—the racial link between Latino school board representatives and the Latino community—has a powerful (albeit largely indirect) effect on substantive outcomes. The election of Latino school board members is statistically related to the number of Latino administrators, which is associated with the number of Latino teachers. In turn, the number of Latino teachers impacts Latino student performance. This is very much in keeping with Meier's (1993) contention that substantive representation is achieved in this policy area because: (1) the demographic characteristic of race (being Latino) is highly salient; (2) policy decisions are directly relevant to the descriptive characteristic in question; and (3) representatives have the discretion to act over administrators, who in turn have discretion over teachers, who in turn influence students. Our results provide more evidence for the “top-down” argument of Latino representation and student performance and offer evidence over time of the translation of descriptive representation to substantive representation.11 Conclusion Past research on Latino representation and Latino educational performance neglected to adequately empirically sort out the direct and indirect effects of representation and student achievement. The central assumption in these studies outlines a casual chain running from Latino political representation—school boards—to Latino bureaucratic representation—administrators and teachers—to Latino student performance. Our results support this argument with a path analytic model and shown the direct and indirect effects of Latino political and bureaucratic representation on Latino student performance. Furthermore, our results establish that descriptive representation does become substantive representation in the area of education policy for Latinos; moreover, we have shown this relationship to hold over time. 11 We perform a number of alternative analyses, to examine whether changes in our independent variables are associated with changes in our dependent variables (and to examine whether increases in representation have different effects than decreases in representation.), and to examine the effect of non-linear effects. These analyses are described in Appendix C. 17 Not only does our model contribute to the body of literature on Latino representation and education, it underscores the importance of school board elections and school district hiring practices. Latino political representation directly and substantially affects the numbers of Latino administrators and teachers. Therefore, policies to promote the representation of Latinos are needed. Specifically, as past research has shown, ward elections should be more widespread in minority Latino districts (Leal, Martinez-Ebers, Meier 2004; Meier, Juenke, Wrinkle, and Polinard, 2005). Furthermore, the hiring practices of school districts should promote minority administration candidates, particularly in minorityprominent districts. Likewise, Latino teacher hiring is important in districts with high percentages of minorities. Sponsorship of Latino administrators and teachers in districts with sizeable Latino student populations may improve educational outcomes, as suggested by our findings. Although our study enhances our understanding of the effect of Latino representation on Latino policy, specifically educational outcomes, there are some limitations that should be remedied in future work. First, the model may need refinement in its specification. Past studies have asserted an interactive effect between Latino school board members and teachers in influencing Latino student performance (Polinard, Wrinkle, and Longoria 1990). In general, given our findings regarding the significant but relatively weak relationship between the presence of Latino teachers and student performance, more research should be done examining the conditions under which the diversity in teaching staff can contribute to student achievement across groups of students. Second, additional dependent variables should be tested. Analyses of Latino representation have employed measures of class assignments (gifted, bilingual, mentally-retarded), drop out rates/graduation rates, and disciplinary actions in determining the effects of political and bureaucratic representation on Latino student performance. More research should be done to examine the political, social, and bureaucratic factors that influence a broad set of achievement measures. And third, more research should be done both examining these issues for other demographic groups (e.g., women, African Americans), as well as examining how the diversity among Latinos may influence the relationships that connect political representation to substantive educational outcomes. 18 Beyond education policy, our study has broad implications for Latino politics and policy. As the Latino population continues to grow, states are the best setting to observe how these demographic changes translate into changes in politics and policy. Our findings indicate that minority representation matters for minority policy, and this should be explored further for other minority groups across diverse policy areas. Even though educational attainment is an axiom in our society, it is clear that understanding the paths involved in translating political and bureaucratic actions into student performance remains a complicated and often ambiguous endeavor. This study provides an illustrative path analytic model for disentangling these relationships. Our results reveal a more comprehensive explanation of how both direct and indirect measures affect Latino education policy. Future research should explore how this process can be altered to provide more tangible and successful outcomes for the largest and most educationally challenged minority group in the country. 19 Figure 1 Percentage Distribution of Public Elementary and Secondary School Students by Race and Ethnicity: 1972-2006 Source: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Science (2008) 20 Figure 2 Conceptual Model of Latino Education % Latino SB + + + + % Latino Admin % Latino Students + + + + % Latino Teachers ± _ Per Pupil + Spending + Teacher Experience + + % All Pass TAAS + + _ + % Low Income 21 _ Pass TAAS % Latino Figure 3. Pathways from School Board Representation to Educational Outcomes .656* Percentage of Administrators Who are Latino .489* Latino Representation on School Boards .008 Percentage Latino Pass TAAS .039* .209* Percentage of teachers that are Latino .129* Control variables for year, teacher experience, instructional spending, and district income included in analysis, but omitted from figure. Non-standardized estimates. 22 Table 1 Path Coefficients: Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects on Latino Educational Performance (standard coefficients shown) Direct .622* .192* .113* -.002 3.179* .474* -.033* .017* Indirect 0 .408 .424 0 0 0 -.113 -.078 Total .622 .601 .537 -.002 3.179 .474 -.146 -.061 Latino Administrators Latino Teachers Latino Student Achievement .656* .209* .039* 0 .321 .053 .656 .530 .092 Latino Administrators Latino Administrators Latino Teachers .489* 0 .489 Latino Student Performance .008 .044 .052 Latino Teachers Latino Student Performance .090* 0 .090 Teacher Experience Overall Student Performance Latino Student Performance .842* 0 .842 .163* .912 1.075 Overall Student Performance Latino Student Performance .005* 0 .005 .001* .006 .007 Low Income Students Overall Student Performance Low Income Students Latino Student Performance -.272* 0 -.272 0 -.294 -.294 1.083* 0 1.081 Latino Students Latino Students Latino Students Latino Students Latino Students Latino Students Latino Students Latino Students Latino SB Members Latino SB Members Latino SB Members Teacher Experience Instructional $ Instructional $ Overall Student Performance Latino SB Members Latino Administrators Latino Teachers Teacher Experience Instructional $ Low Income Students Student Achievement Latino Student Achievement Latino Student Performance 23 Table 1 (Continued): Path Coefficients: Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects on Latino Educational Performance (standard coefficients shown) Y97 Y97 Y97 Y97 Y97 Y97 Y97 Y97 Y97 Latino SB Members Latino Admins. Latino Teachers Teacher Experience Instructional $ Low Income Students Student Performance Latino Student Perform. Latino Students Direct -.855 .480 0 0 0 0 0 0 1.098 Indirect .683 .099 .372 -.002 3.491 .520 -.161 -.121 0 Total -.171 .579 .372 -.002 3.491 .520 -.161 -.121 1.098 Y00 Y00 Y00 Y00 Y00 Y00 Y00 Y00 Y00 Latino SB Members Latino Admins. Latino Teachers Teacher Experience Instructional $ Low Income Students Student Performance Latino Student Perform. Latino Students Direct -.998* .558 0 0 0 0 0 0 2.553* Indirect 1.589 .879 1.116 -.004 8.117 1.210 -.374 -.220 0 Total .591 1.437 1.116 -.004 8.117 1.210 -.374 -.220 2.553 Y98 Y98 Y98 Y98 Y98 Y98 Y98 Y98 Y98 Latino SB Members Latino Admins. Latino Teachers Teacher Experience Instructional $ Low Income Students Student Performance Latino Student Perform. Latino Students -1.103* .627 0 0 0 0 0 0 1.558 .969 .212 .559 -.002 4.952 .738 -.228 -.165 0 -.133 .839 .559 -.002 4.952 .738 -.228 -.165 1.558 Y01 Y01 Y01 Y01 Y01 Y01 Y01 Y01 Y01 Latino SB Members Latino Admins. Latino Teachers Teacher Experience Instructional $ Low Income Students Student Performance Latino Student Perform. Latino Students -.595 -.065 0 0 0 0 0 0 3.223* 2.006 1.546 1.385 -.005 10.247 1.528 -.472 -.256 0 1.411 1.481 1.385 -.005 10.247 1.528 -.472 -.256 3.223 Y99 Y99 Y99 Y99 Y99 Y99 Y99 Y99 Y99 Latino SB Members Latino Admins. Latino Teachers Teacher Experience Instructional $ Low Income Students Student Performance Latino Student Perform. Latino Students -.817 .354 0 0 0 0 0 0 2.040* 1.270 .690 .836 -.003 6.486 .967 -.299 -.182 0 .453 1.043 .836 -.003 6.486 .967 -.299 -.182 2.040 24 Bibliography Aronson, Joshua, Michael J. Lustina, Catherine Good, Kelli Keough, Claude M. Steele, and Joseph Brown. 1999. "When White Men Can't Do Math: Necessary and Sufficient Factors in Stereotype Threat." Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 35(1): 29-46. Bali, Valentina A., Dorothea Anagnostopoulos, and Reginald Roberts. 2005. "Toward a Political Explanation of Grade Retention." Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 27(2): 133-155. Bali, Valentina A. and R. Michael Alvarez. 2004. "The Race Gap in Student Achievement Scores: Longitudinal Evidence from a Racially Diverse School District." Policy Studies Journal 32(3): 393-415. Bratton, Kathleen A. 2006. “The Behavior and Success of Latino Legislators: Evidence from the States.” Social Science Quarterly, 87(5): 1136-1157. Bratton, Kathleen A. and Leonard P. Ray. 2002. "Descriptive Representation, Policy Outcomes, and Municipal Day-Care Coverage in Norway." American Journal of Political Science 46(2): 428-437. Brindis C.D., A.K. Driscoll, M.A. Biggs, and L.T. Valderrama. 2002. “Fact Sheet on Latino Youth: Income and Poverty.” Center for Reproductive Health Research and Policy, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Health Sciences and the Institute for Health Policy Studies. University of California: San Francisco. Canon, David T. 1999. Race, Redistricting and Representation: The Unintended Consequences of Black Majority Districts. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Chubb, John E. and Terry Moe. 1990. Politics, Markets, and America's Schools. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institute. Darder, Antonia, Rodolfo D. Torres, and Henry Gutierrez. 1997. Latinos and Education: A Critical Reader. New York: Routledge. Figlio, David N. 1999. “Functional Form and the Estimated Effects of School Resources.” Economics of Education Review, 18 (2): 241-52. Fraga, Luis R., Kenneth J. Meier, and Robert E. England. 1986. “Hispanic Americans and Educational Policy: Limits to Equal Access.” Journal of Politics, 48 (4): 850-76. Gibson, Margaret A. 2002. “The New Latino Diaspora and Educational Policy.” In Education in the New Latino Diaspora: Policy and the Politics of Identity. Stanton Wortham, Enrique G. Murillo, Enrique G. Murillo Jr, Edmund T. Hamann, eds. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. Hanushek, Eric A. 1981. “Throwing Money at Schools.” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 1 (1): 19-41. Hanushek, E.A. 1998. “Conclusion and Controversies about the Effectiveness of School Resources.” Economic Policy Review, 4 (1): 11-28. Federal Reserve Bank: New York. 25 Haynie, Kerry. 2000. African American Legislators in the American States. New York: Columbia University Press. Hess, Frederick and David Leal. 1997. “Minority Teachers, Minority Students, and College Matriculation: A New Look at the Role-Modeling Hypothesis.” Policy Studies Journal, 25: (Summer): 235-48. Hicklin, Alisa and Kenneth J. Meier. 2008. "Race, Structure, and State Governments: The Politics of Higher Education Diversity." Journal of Politics 70(3): 851-860. Hoyle, Rick H. and Abigail T. Panter. 1995. “Writing About Structural Equation Models.” In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Rick H. Hoyle, ed. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications. Hu, L. and Bentler P.M. 1999. “Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New Alternatives.” Structural Equation Modeling Kerr, Brink. and Will Miller. 1997. “Latino Representation: It’s Direct and Indirect.” American Journal of Political Science, 41 (3): 1066-71. Leal, David L. and Frederick M. Hess. 2000. “The Politics of Education Expenditures in Urban School Districts.” Social Science Quarterly, 81 (4): 1064-1072. Leal, David L., Valerie Martinez-Ebers, and Kenneth J. Meier. 2004. “The Politics of Latino Education: The Biases of At-Large Elections.” The Journal of Politics 66 (4): 1224-44. Lipsky, David. 1980. Street Level Bureaucracy. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. Llagas, Charmaine. 2003. Status and Trends in the Education of Hispanics (NCES 2003-008). Washington DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education. Mansbridge, Jane. 1999. “Should Black Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent Yes.” Journal of Politics 61 (3): 628-57. Meier, Kenneth J. 1993a. “Representative Bureaucracy: A Theoretical and Empirical Exposition.” Research in Public Administration, 2: 1-35. Meier, Kenneth J. 1993b. "Latinos and Representative Bureaucracy: Testing the Thompson and Henderson Hypotheses." Journal of Public Administration Research 3(4): 393-414. Meier, Kenneth J. 2005. "The Texas Minority Education Study." Project for Equity, Representation, and Governance, Texas A&M University. Meier, Kenneth J. and Robert E. England. 1984. "Black Representation and Educational Policy: Are They Related?" American Political Science Review 78(2): 392-403. Meier, Kenneth J., Eric Gonzalez Juenke, Robert D. Wrinkle, J.L. Polinard. 2005. Structural Choices and Representational Biases: The Post-Election Color of Representation. American Journal of Political Science, 49(4): 758-768. 26 Meier, Kenneth J. and Laurence J. O’Toole, Jr. 2006. “Political Control versus Bureaucratic Values: Reframing the Debate.” Public Administration Review. Essays on Reframing Bureaucracy: March-April. Meier, Kenneth J., J.L. Polinard, and Robert D. Wrinkle. 2000. "Bureaucracy and Organizational Performance: Causality Arguments about Schools." American Journal of Political Science 44(3): 590-602. Meier, Kenneth J. and Joseph Stewart Jr. 1991. The Politics of Hispanic Education. Albany: State University of New York Press. Meier, Kenneth J., Joseph Stewart Jr., and Robert E. England. 1991. "The Politics of Bureaucratic Discretion: Educational Access as an Urban Service." American Journal of Political Science 35(1): 155-177. Meier, Kenneth J., Robert D. Wrinkle, and J.L. Polinard. 1999. “Representative Bureaucracy and Distributional Equity: Addressing the Hard Question.” Journal of Politics 61 (4): 1025-39. National Center for Education Statistics. 2002. Status and Trends in the Education of Hispanics. Washington DC. National Center for Education Statistics. 2008. The Condition of Education 2008. Institute of Education Sciences: Washington DC. Nicholson-Crotty, Sean and Kenneth J. Meier. 2002. "Size Doesn't Matter: In Defense of Single-State Studies." State Politics and Policy Quarterly 2(4): 411-422. Pitkin, Hanna. 1967. The Concept of Representation. Berkeley: University of California Press. Polinard, J.L., Robert D. Wrinkle, and Thomas Longoria. 1990. “Education and Governance: Representational Links to Second Generation Discrimination.” The Western Political Quarterly 43 (3): 631-46. Polinard, J.L., Robert D. Wrinkle, and Kenneth J. Meier. 1995 "The Influence of Educational and Political Resources on Minority Students' Success." The Journal of Negro Education 64(4): 463-474. Preuhs, Robert R. 2007. "Descriptive Representation as a Mechanism to Mitigate Policy Backlash." Political Research Quarterly 60(2): 277-292. Riley, Richard W. and Delia Pompa. 1998. Improving Opportunities: Strategies from the Secretary of Education for Hispanic and Limited English Proficient Students. Washington DC: A Response to the Hispanic Dropout Project, U.S. Department of Education. <available at: http://www.ncela.gwu.edu/pubs/hdp/improving.htm> Shockley, J.S. 1974. Chicano Revolt in a Texas Town. University of Notre Dame Press. Slobogin, Kathy. 2001. “Education, Texas Style: Effectiveness of Yearly Testing Questioned.” CNNFYI.com, February 27. <available at: http://cnnstudentnews.cnn.com/2001/fyi/teachers.ednews/02/23/texas.tests/index.html> 27 Smith, Kevin B. and Christopher W. Larimer. 2004. "A Mixed Relationship: Bureaucracy and School Performance." Public Administration Review 64(6): 728-736. Smith, Kevin B. and Kenneth J. Meier. 1994. "Politics, Bureaucrats, and Schools." Public Administration Review 54: 551-558. Steele, Claude M. 1997. "A Threat in the Air: How Stereotypes Shape Intellectual Identity and Performance." American Psychologist 52(6): 613-629. Steele, Claude M. and Aronson, Joshua. 1995. "Stereotype Threat and the Intellectual Test Performance of African-Americans." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69(5): 797811. Stewart, Joseph Jr., Robert E. England, and Kenneth J. Meier. 1989. "Black Representation in Urban School Districts: From School Board to Office to Classroom." Western Political Quarterly 42(2): 287-305. Stokes, Atiya Kai. 2003. “Latino Group Consciousness and Political Participation.” American Politics Research 31 (4): 361-78. Swers, Michele. 2002. The Difference Women Make: The Policy Impact of Women in Congress. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Tate, Katherine. 2003. Black Faces in the Mirror: African Americans and Their Representatives in the U.S. Congress. Princeton: Princeton University Press. U.S. Census Bureau. 2000. “Fast Facts for Congress.” <available at: http://fastfacts.census.gov> Wenglinski, Harold. 1997. “How Money Matters: The Effect of School District Spending on Academic Achievement.” Sociology of Education, 70 (3): 221-37. 28 Table A1. Descriptive Statistics, Independent and Dependent Variables Variable N Mean SD Min. Max. % Latino Students 5,204 27.64 26.70 0 100 % Latino SB Members 5,188 9.40 21.11 0 100 % Latino Administrators 5,194 8.85 21.94 0 100 % Latino Teachers 5,204 8.61 18.56 0 100 Avg. Teacher Experience 5,204 11.93 2.31 Instructional Expenditures per student % Latinos that Pass TAAS 5,199 3,502.53 940.77 4,722 73.07 12.95 0 100 % All Students that Pass TAAS % Low Income 5,201 80.69 9.77 26.7 100 5,204 47.04 19.26 0 100 1997 5,207 .20 .40 0 1 1998 5,207 .20 .40 0 1 1999 5,207 .20 .40 0 1 2000 5,207 .20 .40 0 1 2001 5,207 .20 .40 0 1 29 .80 1,169 20.70 15,537 Appendix B Structural Equation Model: Matrix of Regression Results (Parameter Estimates) Latino Students Latino SB Mem. Latino Admins Latino Teachers Avg. Teacher Exp. Per Pupil Spending Latinos Pass TAAS Students Pass TAAS Low Income Latino Students Latino SB Mem. Latino Admins Latino Teachers Avg. Teacher Exp ______ 0.622* (0.005) ______ 0.192* (0.007) 0.656* (0.009) _____ 0.113* (0.004) 0.209* (0.006) 0.489* (0.006) -0.002 (0.001) _____ 3.179* (0.357) _____ -0.033* (0.007) _____ 0.474* (0.006) _____ _____ _____ 0.017* (0.007) .039* (.011) .008 (.013) _____ _____ 0.113* (0.004) -0.002 (0.001) 0.209* (0.006) 0.489* (0.006) _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ ______ ______ _____ _____ _____ 0.090* (0.018) 0.163* (0.049) 0.842* (0.059) _____ Per Pupil Spending Latinos Pass TAAS Students Pass TAAS Low Income Y97 3.179* (0.357) ______ ______ _____ _____ _____ 0.001* (0.000) 0.005* (0.000) _____ 0.025* (0.007) -0.033* (0.007) 0.474* (0.006) 1.098 (0.876) 1.558 (0.876) 2.040* (0.877) 2.553* (0.877) 3.223* (0.877) ______ ______ 1.081* (0.008) _____ ______ ______ _____ 0.001* (0.000) 0.005* (0.000) _____ _____ ______ 0.165* (0.049) 0.842* (0.059) _____ _____ ______ 0.129* (0.010) _____ -0.855 (0.439) -1.103* (0.439) -0.817 (0.440) -0.998* (0.440) -0.595 (0.440) 0.480 (0.379) 0.627 (0.380) 0.354 (0.380) 0.558 (0.380) -0.065 (0.380) _____ _____ _____ _____ -0.272* (0.010) _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Variables Y98 Y99 Y00 Y01 0.622* (0.000) 0.192* (0.007) 0.656* (0.009) 30 1.083* (0.008) _____ -0.272* (0.010) _____ _____ Appendix C. Alternative Analyses. We conducted a set of alternative analyses, using fixed effect cross-sectional time series models, to examine how changes in diversity among school board officials, administrators, and teachers influenced changes in test scores. The results from these alternative analyses support the path model presented in this paper. When controlling for initial levels of diversity on school boards, among administrators, and among students, in addition to our other control variables, changes in Latino proportion of school board members was positively associated with changes in the Latino proportion of administrators. When controlling for initial levels of diversity among administrators, teachers, and students, as well as our other control variables, changes in the Latino proportion of administrators was positively associated with changes in the Latino proportion of teachers. And, when controlling for initial test scores, and diversity among teachers and students, as well as our other control variables, changes in Latino proportion of teachers was positively associated with changes in test scores. We note that changes in the ethnic composition of the teaching staff appear to have a more powerful effect on changes in test scores than our path model indicated, at least relative to the other factors of Latino representation on the school board and the ethnic composition of the administrative staff. However, as in the findings presented in the paper, the relationship between the percentage of Latino teachers and Latino passage rates is much smaller than the relationship between teacher experience and Latino passage rates. We also observe that the influence of Latino school board representation on the ethnic composition of administrative staff is significant regardless of the time lag considered (two years, three years, four years, or five years). The same is true of the influence of the ethnic composition of administrative staff on the ethnic composition of teaching staff. However, changes in the proportion of Latino teachers significantly influences changes in test scores only across a twoyear period. This is consistent with educational research (e.g. Aronson et al 1999) that indicates that test scores respond to very immediate, situation-specific factors. We also tested for non-linear relationships in alternative OLS models. The OLS results indicate that Latino representation on school boards had a positive effect on the percentage of Latino administrators—but that this effect was less evident in districts where Latino administrators made up a relatively high proportion of administrators. Likewise, the percentage of Latino teachers was positively associated with Latino passage rates, but the effect was less evident in districts with a relatively high proportion of Latino teachers. The results for the cross-sectional time series analyses examining the influence of changes in school board composition, and changes in the composition of administrative and teaching staff, showed no evidence of significant non-linear effects. This makes sense, given that change should predict change in a relatively linear fashion. Our control variables (such as instructional spending, financial resources within the population, and teacher experience) address the possibility that our results are an artifact of the likelihood that districts with a more educated Latino labor force (and thus more Latino teachers) are generally those where Latino students perform well on basic skills exams. However, to further examine these relationships, we also conducted additional alternative cross-sectional panel analyses, which analyze the effect of gains in representation separately from the effect of losses. We find that across two-year periods, gains in Latino representation on school boards leads to increases in the percentage of administrators who are Latino, which in turn leads to gains in the percentage of teachers who are Latino, which in turn leads to an increase in Latino test scores. Most interestingly, the reverse pattern is observed for reductions in Latino representation—when Latino representation drops, the percentage of Latino administrators drops, the percentage of 31 Latino teachers drops, and Latino scores drop .Given that there is little reason to believe that a smaller Latino population would equate a less educated Latino population, this suggests that the relationships we find are indeed due to the involvement of Latinos in education policy, rather than to community demographics. Below, we present the results from the alternative analyses predicting change across two-year intervals. The full set of alternative analyses are available from the author. 32 Table C1. Influences on Change in % Latino Administrators, % Latino Teachers, % Latino Passing TAAS (Change measured across two year intervals.) Change, % Latino Change, % Change, % Administrators Latino Latino Pass Teachers TAAS Change, % Latino Teachers .153* (.052) Change, % Latino Administrators .023* -.006 (.004) (.017) Change, % Latino School Board .093* .001 .045* Rep. (.013) (.004) (.017) Change, Low Income -.019 -.011* .016 (.012) (.004) (.017) Change, % Latino Students .073* .029* -.268* (.039) (.013) (.061) Change, Instructional Spending .104 .036 .165 (.162) (.056) (.266) * Change, Teacher Experience .064 -.070 .293* (.054) (.019) (.088) Change, Overall Passage Rates .604* (.018) * Lagged % Latino School Board .080 -.001 .067* Rep (.016) (.006) (.021) Lagged % Latino Administrators -1.018* .053* .027 (.014) (.006) (.026) Lagged % Latino Students .069 .021 -.390* (.042) (.014) (.065) Lagged % Latino Teachers -.793* .268* (.013) (.066) Lagged % Latino Pass TAAS -.832* (.012) 1995 -.661* -1.140 -27.074* (.291) (.101) (.605) 1996 -.618* -.864 -21.887* (.277) (.096) (.525) 1997 -.614* -.604 -15.368* (.272) (.094) (.481) 1998 -.376 -.354 -9.163* (.265) (.091) (.432) 1999 -.282 -.211 -4.673* (.257) (.088) (.379) 2000 .071 -.099 -2.330* (.252) (.086) (.357) * * Constant 6.451 6.176 72.857* (1.220) (.428) (2.412) Sample Size 7,185 7,184 Groups 1,038 1,038 Within R2 .48 .40 *: p≤ .05, one tailed test. Standard Errors in Parenthesis 33