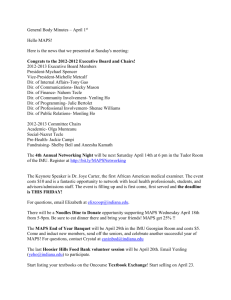

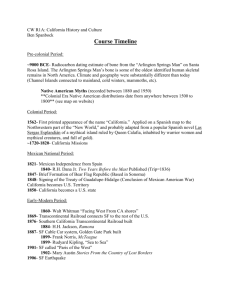

Jennifer Koons, 2008S

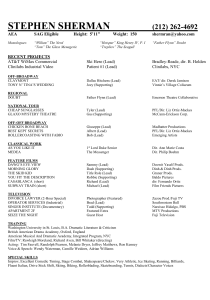

advertisement