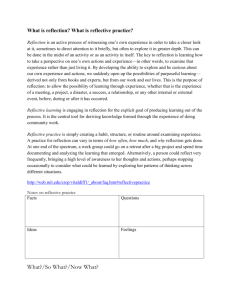

New Art and Reflective Discourse

advertisement