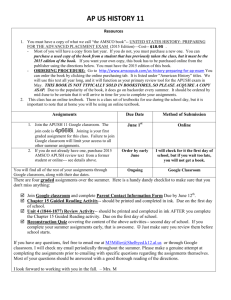

File - Mr. Heasman's

advertisement

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

1 - Black Power

Malcolm X – “The Ballot or the Bullet” – speech given in Detroit in 1964. By this time, Malcolm

X had left the Nation of Islam.

“If we don’t do something real soon, I think you’ll have to agree that we’re going to be forced either

to use the ballot or the bullet. It’s one or the other in 1964. It isn’t that time is running out—time has

run out! 1964 threatens to be the most explosive year America has ever witnessed. The most

explosive year. Why? It’s also a political year. It’s the year when all of the white politicians will be

back in the so-called Negro community jiving you and me for some votes. The year when all of the

white political crooks will be right back in your and my community with their false promises,

building up our hopes for a letdown, with their trickery and their treachery, with their false promises

which they don’t intend to keep. As they nourish these dissatisfactions, it can only lead to one thing,

an explosion; and now we have the type of black man on the scene in America today. . .who just

doesn’t intend to turn the other cheek any longer. . . .

. . . Being here in America doesn’t make you an American. Being born here in America doesn’t make

you an American. Why, if birth made you American, you wouldn’t need any legislation; you

wouldn’t need any amendments to the Constitution; you wouldn’t be faced with civil-rights

filibustering in Washington, D.C., right now. They don’t have to pass civil-rights legislation to make

a Polack an American.

No, I’m not an American. I’m one of the 22 million black people who are the victims of

Americanism. One of the 22 million black people who are the victims of democracy, nothing but

disguised hypocrisy. So, I’m not standing here speaking to you as an American, or a patriot, or a

flag-saluter, or a flag-waver—no, not I. I’m speaking as a victim of this American system. And I see

America through the eyes of the victim. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American

nightmare.”

Stokely Carmichael, Black Power Address at UC Berkeley, October 1966, Berkeley, CA

“. . . So the question, then, clearly, is. . .Who has power? Who has power to make his or her acts

legitimate? That is all. And that this country, that power is invested in the hands of white people,

and they make their acts legitimate. It is now, therefore, for black people to make our acts

legitimate.

Now we are now engaged in a psychological struggle in this country, and that is whether or not

black people will have the right to use the words they want to use without white people giving

their sanction to it; and that we maintain, whether they like it or not, we gonna use the word

"Black Power". . .but that we are not going to wait for white people to sanction Black Power.

We’re tired waiting; every time black people move in this country, they’re forced to defend their

position before they move. It’s time that the people who are supposed to be defending their

position do that. That's white people. They ought to start defending themselves as to why they

have oppressed and exploited us.

. . . And in order to get out of that oppression one must wield the group power that one has, not

the individual power which this country then sets the criteria under which a man may come into

it. That is what is called in this country as integration: "You do what I tell you to do and then

we’ll let you sit at the table with us." And that we are saying that we have to be opposed to that.

1

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

We must now set up criteria and that if there's going to be any integration, it's going to be a twoway thing. If you believe in integration, you can come live in Watts. You can send your children

to the ghetto schools. Let’s talk about that. If you believe in integration, then we’re going to start

adopting us some white people to live in our neighborhood.

. . . We are on the move for our liberation. We have been tired of trying to prove things to white

people. We are tired of trying to explain to white people that we’re not going to hurt them. We

are concerned with getting the things we want, the things that we have to have to be able to

function. The question is, Can white people allow for that in this country? The question is, Will

white people overcome their racism and allow for that to happen in this country? If that does not

happen, brothers and sisters, we have no choice but to say very clearly, "Move over, or we’re

going to move on over you."

Black Panther Party, excerpt from The Ten Point Program, 1967. Inspired by the black

nationalism of Malcolm X, and by the actions of Stokely Carmichael in Alabama, founders Bobby

Seale and Huey Newton formed a self-defence group in Oakland in 1966. As well as an armed

presence on the streets, the Panthers also offered free legal advice and community education

programs. The organization effectively dissolved in the 1970's as a result of internal disputes,

murders of key members, and FBI harassment.

"What We Believe:

We believe that Black People will not be free until we are able to determine our own

destiny.

We believe that the federal government is responsible and obligated to give every man

employment or a guaranteed income. We believe that if the White American business

men will not give full employment, then the means of production should be taken from

the businessmen and placed in the community so that the people of the community can

organize and employ all of its people and give a high standard of living.

We believe that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the

overdue debt of forty acres and two mules. Forty acres and two mules was promised 100

years ago as redistribution for slave labor and mass murder of Black people. We will

accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. . .

We believe that if the White landlords will not give decent housing to our Black

community, then the housing and the land should be made into cooperatives so that our

community, with government aid, can build and make a decent housing for its people.

We believe in a educational system that will give our people a knowledge of self...

We believe that Black people should not be forced to fight in the military service to

defend a racist government that does not protect us. We will not fight and kill other

people of color in the world who, like Black people, are being victimized by the White

racist government of America. We will protect ourselves from the force and violence of

the racist police and the racist military, by whatever means necessary.

We believe we can end police brutality in our Black community by organizing Black selfdefense groups that are dedicated to defending our Black community from racist police

oppression and brutality. The second Amendment of the Constitution of the United States

gives us the right to bear arms. We therefore believe that all Black people should arm

themselves for self-defense.

2

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

We believe that all Black people should be released from the many jails and prisons

because they have not received a fair and impartial trial.

We believe that the courts should follow the United States Constitution so that Black

people will receive fair trials. The 14th Amendment of the U.S Constitution gives a man

a right to be tried by his peers. A peer is a persons from a similar economic, social,

religious, geographical, environmental, historical, and racial background. To do this the

court will be forced to select a jury from the Black community from which the Black

defendant came. We have been, and are being tried by all White juries that have no

understanding of “the average reasoning man” of the Black community.

When in the course of human events, it become necessary for one people to dissolve the

political bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume among the

powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and

nature’s god entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they

should declare the causes which impel them to separation. We hold these truths to be selfevident, and that all men are created equal that among these are life, liberty, and the

pursuit of happiness. That to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men,

deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,--that whenever any form of

government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or

abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles and

organizing its power in a such a form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their

safety and happiness. . . and to provide new guards of their future security."

3

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

4

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

2 - New Left & Counterculture

Excerpt from the Port Huron Statement, issued by Students For A Democratic Society, 1962

We believe that the universities are an overlooked seat of influence.

First, the university is located in a permanent position of social influence. Its

educational function makes it indispensable and automatically makes it a crucial

institution in the formation of social attitudes. Second, in an unbelievably complicated

world, it is the central institution for organizing, evaluating, and transmitting

knowledge. Third, the extent to which academic resources presently is used to buttress

immoral social practice is revealed first, by the extent to which defense contracts make

the universities engineers of the arms race. Too, the use of modern social science as a

manipulative tool reveals itself in the "human relations" consultants to the modern

corporation, who introduce trivial sops to give laborers feelings of "participation" or

"belonging", while actually deluding them in order to further exploit their labor. And,

of course, the use of motivational research is already infamous as a manipulative aspect

of American politics. But these social uses of the universities' resources also

demonstrate the unchangeable reliance by men of power on the men and storehouses of

knowledge: this makes the university functionally tied to society in new ways,

revealing new potentialities, new levers for change. Fourth, the university is the only

mainstream institution that is open to participation by individuals of nearly any

viewpoint.

. . . But we need not indulge in allusions: the university system cannot complete a

movement of ordinary people making demands for a better life. From its schools and

colleges across the nation, a militant left might awaken its allies, and by beginning the

process towards peace, civil rights, and labor struggles, reinsert theory and idealism

where too often reign confusion and political barter. The power of students and faculty

united is not only potential; it has shown its actuality in the South, and in the reform

movements of the North.

The bridge to political power, though, will be built through genuine cooperation,

locally, nationally, and internationally, between a new left of young people, and an

awakening community of allies. In each community we must look within the university

and act with confidence that we can be powerful, but we must look outwards to the less

exotic but more lasting struggles for justice.

To turn these possibilities into realities will involve national efforts at university reform

by an alliance of students and faculty. They must wrest control of the educational

process from the administrative bureaucracy. They must make fraternal and functional

5

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

contact with allies in labor, civil rights, and other liberal forces outside the campus.

They must import major public issues into the curriculum -- research and teaching on

problems of war and peace is an outstanding example. They must make debate and

controversy, not dull pedantic cant, the common style for educational life. They must

consciously build a base for their assault upon the loci of power.

As students, for a democratic society, we are committed to stimulating this kind of

social movement, this kind of vision and program is campus and community across the

country. If we appear to seek the unattainable, it has been said, then let it be known that

we do so to avoid the unimaginable.

Bob Dylan, Masters of War (1963)

Come you masters of war

You that build the big guns

You that build the death planes

You that build all the bombs

You that hide behind walls

You that hide behind desks

I just want you to know

I can see through your masks

You that never done nothin'

But build to destroy

You play with my world

Like it's your little toy

You put a gun in my hand

And you hide from my eyes

And you turn and run farther

When the fast bullets fly

...

You fasten all the triggers

For the others to fire

Then you set back and watch

While the death count gets higher

Then you hide in your mansion

As young people's blood

Flows out of their bodies

And is buried in the mud

Let me ask you one question

Is your money that good

Will it buy you forgiveness

Do you think that it could

I think you will find

When your death takes its toll

All the money you made

Will never buy back your soul. . .

The Yippies go to Wall Street - excerpt from "A Yippie Manifesto" by Jerry Rubin.

The Youth International Party, or Yippies, had no formal leadership structure and once

nominated a pig ('Pigasus the Great') as a presidential candidate at the 1968 Democratic Party

convention. Noted members Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin were once subpoenaed to appear

before the House Un-American Activities Committee as suspected communists - Hoffman

dressed up as an 18th century soldier from the Revolutionary War, and declared himself to be a

descendent of Jefferson and Washington. Rubin went before the Committee dressed in a VietCong flag. Their protest methods were theatrical, bizarre, and provocative. One example was

their August, 1967, visit to the New York Stock Exchange, as retold by Jerry Rubin.

"We are born twice. My first birth was in 1938, but I was reborn in Berkeley in 1964 in the Free

Speech movement. When we say “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” we’re talking about the second

birth. I got 26 more years. When people 40 years old come up to me and say, “Well, I guess I

6

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

can’t be part of your movement,” I say, “What do you mean? You could have been born

yesterday. Age exists in your head.”

Another yippie saying is “THE GROUND YOU STAND ON IS LIBEATED TERRITORY!”

Everybody in this society is a policeman. We all police ourselves. When we free ourselves, the

real cops take over. I don’t smoke pot in public often, although I love to. I don’t want to be

arrested: that’s the only reason. I police myself.

We do not own our own bodies. We fight to regain our bodies…to make love in the parks, say

“fuck” on television, do what we want to do whenever we want to do it. Prohibitions should be

prohibited. Rules are made to be broken. Never say “no.”

The yippies say: “PROPERTY IS THEFT.’ What America got, she stole. How was this country

built? By the forced labor of slaves. America owes black people billions in compensation.

“Capitalism” is just a polite schoolbook way of saying: “Stealing.” Who deserves what they get

in America? Do the Rockefellers deserve their wealth? HELL NO!

America says that people work only for money. But check it out: those who don’t have money

work the hardest, and those who have money take very long lunch hours. When I was born I had

food on my table and a roof over my head. Most babies born in the world face hunger and cold.

What is the difference between them and me? Every well-off white American better ask himself

that question or he will never understand why people hate America. The enemy is this dollar bill

right here in my hand. Now if I get a match, I’ll show you what I think of it.

This burning gets some political radicals very uptight. I don’t know exactly why. They burn a lot

of money putting out leaflets nobody reads. I think it is more important today to burn a dollar bill

than it is to burn a draft card. “Humm, pretty resilient. Hard to burn. Anybody got a lighter?”

We go to the New York Stock Exchange, about 20 of us, our pockets stuffed with dollar bills.

We want to throw real dollars down at all those people on the floor playing monopoly games

with numbers. An official stops us at the door and says, “You can’t come in. You are hippies and

you are coming to demonstrate.” With TV cameras flying away, we reply: “Hippies?

Demonstrate? We’re Jews. And we’re coming to see the stock market.”

Well, that gets the guy uptight, and he lets us in. We get to the top, and the dollars start raining

down on the floor below. These guys deal in millions of dollars as a game, never connecting it to

people starving. Have they ever seen a real dollar bill?

This is what it is all about, you sonavabitches!!” Look at them: wild animals chasing and fighting

each other over dollar bills thrown by the hippies! And then someone calls the cops . The cops

are a necessary part of any demonstration; always include a role for the cops. Cops legitimize

demonstrations.

The cops throw us out. It is noon. Wall Street Businessmen with briefcases and suits and ties.

Money freaks going to lunch. Important business deals. Time. Appointments. And there we are

in the middle of it, burning five-dollar bills. Burning their world. Burning their Christ.

7

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

“Don’t, Don’t!” some scream, grasping for the sacred paper. Several near fist-fights break out.

We escape with our lives.

Weeks later The New York Times publishes a short item revealing that the New York Stock

Exchange is installing a bullet-proof glass window between the visitor’s platform and the floor,

so that 'nobody can shoot a stockbroker.'"

Communiqué #4 from The Weatherman Underground, 1970

From /San Francisco Good Times/, September 18, 1970. /San Francisco Good

Times/.

September 15, 1970. This is the fourth communication from the Weatherman

Underground.

The Weatherman Underground has had the honor and pleasure of helping Dr.

Timothy Leary escape from the POW camp at San Luis Obispo, California.

Dr. Leary was being held against his will and against the will of

millions of kids in this country. He was a political prisoner, captured

for the work he did in helping all of us begin the task of creating a

new culture on the barren wasteland that has been imposed on this

country by Democrats, Republicans, Capitalists and creeps.

LSD and grass, like the herbs and cactus and mushrooms of the American

Indians and countless civilizations that have existed on this planet,

will help us make a future world where it will be possible to live in peace.

Now we are at war.

With the NLF and the North Vietnamese, with the Democratic Front for the

Liberation of Palestine and Al Fatah, with Rap Brown and Angela Davis,

with all black and brown revolutionaries, the Soledad brothers and all

prisoners of war in Amerikan concentration camps we know that peace is

only possible with the destruction of U.S. imperialism.

Our organization commits itself to the task of freeing these prisoners

of war.

We are outlaws, we are free!

(signed) Bernardine Dohrn

8

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

3 - La Raza & Chicano Movement

Representative Henry B. Gonzalez, in a speech to Congress, April 1969

"I, and many other residents of my part of Texas and other Southwestern States--happen to be

what is commonly referred to as a Mexican American.... What is he to be? Mexican? American?

Both? How can he choose? Should he have pride and joy in his heritage, or bear it as a shame

and sorrow? Should he live in one world or another, or attempt to bridge them both?

There is comfort in remaining in the closed walls of a minority society, but this means making

certain sacrifices; but it sometimes seems disloyal to abandon old ideas and old friends; you

never know whether you will be accepted or rejected in the larger world, or whether your old

friends will despise you for making a wrong choice. For a member of this minority, like any

other, life begins with making hard choices about personal identity. These lonely conflicts are

magnified in the social crises so clearly evident all over the Southwest today. There are some

groups who demand brown power, some who display a curious chauvinism, and some who affect

the other extreme. There is furious debate about what one should be and what one should do.... I

understand all this, but I am profoundly distressed by what I see happening today.... Mr. Speaker,

the issue at hand in this minority group today is hate, and my purpose in addressing the House is

to state where I stand: I am against hate and against the spreaders of hate; I am for justice, and

for honest tactics in obtaining justice.

The question facing the Mexican-American people today is what do we want, and how do we get

it?

What I want is justice. By justice I mean decent work at decent wages for all who want work;

decent support for those who cannot support themselves; full and equal opportunity in

employment, in education, in schools; I mean by justice the full, fair, and impartial protection of

the law for every man; I mean by justice decent homes; adequate streets and public services....

I do not believe that justice comes only to those who want it; I am not so foolish as to believe

that good will alone achieves good works. I believe that justice requires work and vigilance, and

I am willing to do that work and maintain that vigilance...."

9

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

Proclamation of the Delano Grape Workers, 1969

Annotation: Dolores Huerta, the co-founder of the United Farm Workers, led the Delano grape

boycott while raising eleven children. Born in a small New Mexico mining town, Huerta grew up

in Stockton, CA. In 1962 she joined Cesar Chavez in forming the United Farm Workers. While

Chavez spent time with workers in the fields, she did much of the negotiation and legislative

lobbying. She also organized voter registration drives and taught citizenship classes. She also

organized successful 1970 and 1975 grape boycotts. This is an excerpt from her proclamation

announcing the boycott of grape growers in Delano, CA.

"We, the striking grape workers of California, join on this International Boycott Day with the

consumers across the continent in planning the steps that lie ahead on the road to our liberation.

As we plan, we recall the footsteps that brought us to this day and the events of this day. The

historic road of our pilgrimage to Sacramento later branched out, spreading like the unpruned

vines in struck fields, until it led us to willing exile in cities across this land. There, far from the

earth we tilled for generations, we have cultivated the strange soil of public understanding,

sowing the seed of our truth and our cause in the minds and hearts of men.

We have been farm workers for hundreds of years and pioneers for seven. Mexicans, Filipinos,

Africans and others, our ancestors were among those who founded this land and tamed its natural

wilderness. But we are still pilgrims on this land, and we are pioneers who blaze a trail out of the

wilderness of hunger and deprivation that we have suffered even as our ancestors did. We are

conscious today of the significance of our present quest. If this road we chart leads to the rights

and reforms we demand, if it leads to just wages, humane working conditions, protection from

the misuse of pesticides, and to the fundamental right of collective bargaining, if it changes the

social order that relegates us to the bottom reaches of society, then in our wake will follow

thousands of American farm workers. Our example will make them free. But if our road does not

bring us to victory and social change, it will not be because our direction is mistaken or our

resolve too weak, but only because our bodies are mortal and our journey hard. For we are in the

midst of a great social movement, and we will not stop struggling 'til we die, or win!

We have been farm workers for hundreds of years and strikers for four. It was four years ago that

we threw down our plowshares and pruning hooks. These Biblical symbols of peace and

tranquility to us represent too many lifetimes of unprotesting submission to a degrading social

system that allows us no dignity, no comfort, no peace. We mean to have our peace, and to win it

without violence, for it is violence we would overcome-the subtle spiritual and mental violence

of oppression, the violence subhuman toil does to the human body. . .

We have been farm workers for hundreds of years and boycotters for two. We did not choose the

grape boycott, but we had chosen to leave our peonage, poverty and despair behind. Though our

first bid for freedom, the strike, was weakened, we would not turn back. The boycott was the

only way forward the growers left to us. We called upon our fellow men and were answered by

consumers who said--as all men of conscience must--that they would no longer allow their tables

to be subsidized by our sweat and our sorrow: They shunned the grapes, fruit of our affliction.

We marched alone at the beginning, but today we count men of all creeds, nationalities, and

occupations in our number. Between us and the justice we seek now stand the large and powerful

grocers . . . The consumers who rally behind our cause are responding as we do to such

10

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

treatment-with a boycott! They pledge to withhold their patronage from stores that handle grapes

during the boycott, just as we withhold our labor from the growers until our dispute is resolved.

Grapes must remain an unenjoyed luxury for all as long as the barest human needs and basic

human rights are still luxuries for farm workers. The grapes grow sweet and heavy on the vines,

but they will have to wait while we reach out first for our freedom. The time is ripe for our

liberation."

Chicano Rock

From "American Sabor: Latinos in Popular American Music", Smithsonian Institute, Web.

(accessed April 23rd, 2015)

Chicano rock is the distinctive style of rock and roll music performed by Mexican

Americans from East L.A. and Southern California that contains themes of our cultural

experiences. Although the genre is broad and diverse, encompassing a variety of styles and

subjects, the overarching theme of Chicano rock is its R&B influence and incorporation of brass

instruments like the saxophone and trumpet, Farfisa or Hammond B3 organ, funky basslines, and

its blending of Mexican vocal stylings sung in English.

The famous pioneers of the genre are Ritchie Valens -- the first Mexican-American star

and one of The Beatles’ major influences, who died at 17 in the 1959 plane crash that also

claimed Buddy Holly -- and Sunny & the Sunglows, who formed the same year Valens died.

Teenage Chicana vocalists like Rosie Mendez-Hamlin of Rosie and The Originals inspired the

likes of John Lennon with her hit “Angel Baby.”

Chicano rock, like early rock and roll music, adopted the rhythm and blues-based style of

African American music and utilized a then little-known new instrument, the electric guitar. It

also melded influences from Latin American music and included themes of the Chicano culture

of the southwest.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Don Tosti and Lalo Guerrero used jump blues as a

platform to develop what would become Chicano rock. In the early 1960s scores of teenaged

bands with dreams of becoming as famous as Valens practiced their chops in weekly battle of the

bands hosted at churches, high schools and union halls. Noting the unique Latino feel to the way

these bands played R&B, manager/producer Eddie Davis dreamt of creating a Latino-flavored

Motown on their Rampart Record label. The label bore three Chicano rock national hits:

“Farmer John,” “La, La, La, La” and “Land of a 1000 Dances.” These hits, including “Whittier

Boulevard” by Thee Midniters, influenced garage bands around the country and popularized the

inexpensive farfisa organ used by other Mexican American-led bands like Michigan-based ?

(Question Mark) and The Mysterians. In the 1960s and '70s, Chicano popular groups like The

Cannibal and The Headhunters, The Premiers, The Blendells, Sir Douglas Quintet, Thee

Midniters, Los Lobos, El Chicano and others sustained the Chicano rock genre.

Evolving over the years, it is still present in many forms today from more traditional

groups reminiscent of the early pioneers, like Los Lonely Boys to progressive artists like

Quetzal, Rage Against the Machine, Mars Volta, and Texas-based Girl In A Coma among others.

In its multiple incarnations, Chicano rock remains at the forefront of popular rock and roll music.

11

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

12

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

4 - Second Wave Feminism

National Organization for Women, Statement of Purpose, October 29, 1966

"There is no civil rights movement to speak for women, as there has been for Negroes and other

victims of discrimination. The National Organization for Women must therefore begin to speak.

WE BELIEVE that the power of American law, and the protection guaranteed by the

U.S. Constitution to the civil rights of all individuals, must be effectively applied and enforced to

isolate and remove patterns of sex discrimination, to ensure equality of opportunity in

employment and education, and equality of civil and political rights and responsibilities on

behalf of women, as well as for Negroes and other deprived groups.

WE DO NOT ACCEPT the token appointment of a few women to high-level positions in

government and industry as a substitute for a serious continuing effort to recruit and advance

women according to their individual abilities. To this end, we urge American government and

industry to mobilize the same resources of ingenuity and command with which they have solved

problems of far greater difficulty than those now impeding the progress of women.

WE BELIEVE that this nation has a capacity at least as great as other nations, to innovate

new social institutions which will enable women to enjoy true equality of opportunity and

responsibility in society. . .We do not accept the traditional assumption that a woman has to

choose between marriage and motherhood, on the one hand, and serious participation in industry

or the professions on the other….True equality of opportunity and freedom of choice for women

requires such practical and possible innovations as a nationwide network of child-care centers. . .

and national programs to provide retraining for women who have chosen to care for their own

children full time.

WE BELIEVE that it is as essential for every girl to be educated to her full potential of

human ability as it is for every boy. . . We believe that American educators are capable of

devising means of imparting such expectations to girl students. Moreover, we consider the

decline in the proportion of women receiving higher and professional education to be evidence of

discrimination. . .

WE REJECT the current assumptions that a man must carry the sole burden of supporting

himself, his wife, and family, and that a woman is automatically entitled to lifelong support by a

man upon her marriage, or that marriage, home and family are primarily woman’s world and

responsibility—hers, to dominate, his to support. We believe that a true partnership between the

sexes demands a different concept of marriage, and equitable sharing of the responsibilities of

home and children and of the economic burdens of their support. We believe that proper

recognition should be given to the economic and social value of homemaking and child care. . .

WE BELIEVE that women must now exercise their political rights and responsibilities as

American citizens. They must refuse to be segregated on the basis of sex into separate-and-notequal ladies’ auxiliaries in the political parties. . .

IN THE INTERESTS OF THE HUMAN DIGNITY OF WOMEN, we will protest and

endeavor to change the false image of women now prevalent in the mass media, and in the texts,

ceremonies, laws, and practices of our major social institutions. . . We are similarly opposed to

all policies and practices—in church, state, college, factory, or office—which, in the guise of

protectiveness, not only deny opportunities by also foster in women self-denigration,

dependence, and evasion of responsibility, undermine their confidence in their own abilities and

foster contempt for women.

13

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

Excerpt From The Feminine Mystique, by Betty Friedan (1962).

The problem lay buried, unspoken, for many years in the minds of American women. It

was a strange stirring, a sense of dissatisfaction, a yearning that women suffered in the middle of

the twentieth century in the United States. Each suburban wife struggled with it alone. As she

made the beds, shopped for groceries, matched slipcover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches

with her children, chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies, lay beside her husband at night — she

was afraid to ask even of herself the silent question — "Is this all?"

For over fifteen years there was no word of this yearning in the millions of words written

about women, for women, in all the columns, books and articles by experts telling women their

role was to seek fulfillment as wives and mothers. Over and over women heard in voices of

tradition and of Freudian sophistication that they could desire no greater destiny than to glory in

their own femininity. Experts told them how to catch a man and keep him, how to breastfeed

children and handle their toilet training, how to cope with sibling rivalry and adolescent

rebellion; how to buy a dishwasher, bake bread, cook gourmet snails, and build a swimming pool

with their own hands; how to dress, look, and act more feminine and make marriage more

exciting; how to keep their husbands from dying young and their sons from growing into

delinquents.

In the fifteen years after World War II, this mystique of feminine fulfillment became the

cherished and self-perpetuating core of contemporary American culture. Millions of women

lived their lives in the image of those pretty pictures of the American suburban housewife,

kissing their husbands goodbye in front of the picture window, depositing their stationwagonsful

of children at school, and smiling as they ran the new electric waxer over the spotless kitchen

floor. They baked their own bread, sewed their own and their children's clothes, kept their new

washing machines and dryers running all day. They changed the sheets on the beds twice a week

instead of once, took the rug-hooking class in adult education, and pitied their poor frustrated

mothers, who had dreamed of having a career. Their only dream was to be perfect wives and

mothers; their highest ambition to have five children and a beautiful house, their only fight to get

and keep their husbands. They had no thought for the unfeminine problems of the world outside

the home; they wanted the men to make the major decisions. They gloried in their role as

women, and wrote proudly on the census blank: "Occupation: housewife."

14

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

Barbara Charline Jordan, 1976 Democratic National Convention Keynote Address

Barbara Jordan was the first African-American elected to the Texas State Senate, and the first

black Texan to represent the state in Congress (as Representative for Houston). This is an

excerpt from her speech that opened the Democratic National Convention in 1976.

"It was one hundred and forty-four years ago that members of the Democratic Party first met in

convention to select a Presidential candidate. Since that time, Democrats have continued to

convene once every four years and draft a party platform and nominate a Presidential candidate.

And our meeting this week is a continuation of that tradition. But there is something different

about tonight. There is something special about tonight. What is different? What is special?

I, Barbara Jordan, am a keynote speaker.

When -- A lot of years passed since 1832, and during that time it would have been most unusual

for any national political party to ask a Barbara Jordan to deliver a keynote address. But tonight,

here I am. And I feel -- I feel that notwithstanding the past that my presence here is one

additional bit of evidence that the American Dream need not forever be deferred. . .

. . . We are a people in a quandary about the present. We are a people in search of our future. We

are a people in search of a national community. We are a people trying not only to solve the

problems of the present, unemployment, inflation, but we are attempting on a larger scale to

fulfill the promise of America. We are attempting to fulfill our national purpose, to create and

sustain a society in which all of us are equal. . ."

15

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

16

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

5 - Environmentalist Movement

Everyone’s Backyard: The Love Canal Chemical Disaster, by Amy M. Hay. This is an edited

version of an essay by Hay published by the Gilder Lehrman Institute for American History. Amy

Hay is Associate Professor of History at the University of Texas

.

It all started quietly. Most people living in the LaSalle neighborhood of Niagara Falls,

New York, first heard about problems in the spring of 1978 when scientists from the

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) appeared on their streets. These officials were looking

for the source of chemical contamination in nearby Lake Ontario. Since the beginning of the

twentieth century, but especially during and after WWII, Niagara Falls had become the home to

a thriving chemical industry, attracted in part by cheap hydroelectric power. Plans to produce

power dated as far back as the 1880s. One spectacular failure occurred when local entrepreneur

William Love dug a canal, which would have linked two different elevations of the Niagara

River to generate electricity. The economic crash of 1883 and Nikola Tesla’s discovery of

alternating currents ended Love’s project, leaving a trench approximately one mile long and as

deep as forty feet in some places. The spot later became a municipal dumpsite and local

swimming hole. Hooker Chemical bought the land in the 1940s and used it to dispose of over

twenty thousand tons of industrial chemical waste. The company covered the site with a clay cap

and in 1952 sold it to the Niagara Falls Board of Education for $1, with the understanding that

the company could not be held responsible for any future problems. Over the next two decades,

barrels of chemicals sometimes surfaced, and families living in the suburban neighborhood that

grew up around the 97th Street School frequently replaced their basement sump pumps. With the

appearance of the EPA scientists, residents slowly became aware that their middle-class

neighborhood had been built above the abandoned toxic waste landfill. The Love Canal chemical

disaster had begun.

Love Canal represented a different kind of environmental calamity, one in which the

pollution remained mostly invisible and odorless, the hazards uncertain, and the response

indifferent at best, uncaring and criminal at worst. . . For Love Canal’s residents, the discovery

of hazardous chemicals buried in their ordinary, typical suburban neighborhood sparked health

concerns, challenged notions of citizenship, and increased expectations of the state. They went

from viewing their neighborhood as part of a productive and prosperous industrial city to a

contaminated landscape, unfit for families or homes. Examining the stories that residents,

scientific experts, and community advocates told about the disaster, it becomes clear that Love

Canal marked the advent of working-class activism, presented new challenges for public health

departments, and spurred the beginnings of the environmental justice movement.

. . . Residents organized informally, over back fences and kitchen tables, with women leading the

mobilization efforts. Awareness of the contamination spread when local homemaker Lois Gibbs

revealed that her son Michael had begun experiencing seizures. She contacted local officials to

see if she could send Michael to another school, as the 99th Street Elementary School was

located directly over the abandoned landfill. Her request was denied, and she started a petition to

have the school closed. She went from door to door, talking with women in their backyards and

across their kitchen tables. Local families grew increasingly anxious as more information was

released, and it became clear that hazardous chemicals were leaking out and exposing family and

friends to a toxic stew. Gibbs, her husband, and a friend, Debbie Cerillo, attended a public health

meeting held in the state capital of Albany, where they challenged the state’s remediation plans

17

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

for the area. Traveling back to Niagara Falls, they found residents protesting, burning property

deeds in barrels. Gibbs spoke to the crowd, and the residents agreed to hold a neighborhood

meeting the next day. At that meeting Gibbs was elected the president of the Love Canal

Homeowners’ Association. At first the Homeowners’ Association appeared to have prevailed, as

New York state officials agreed to relocate families living closest to the landfill. The state

refused, however, to move the remaining 700 residents living in the streets beyond. In the

opinion of Department of Health administrators, the evacuated area provided a more-than-ample

buffer zone between the contaminated inner-ring homes and those built farther away. Governor

Hugh Carey assured residents that if more chemical-related illnesses could be proven in these

outer rings, then those residents would also be relocated. Instead of providing surety, the

boundary had the unintended effect of solidifying a group identity and raised the stakes for

families living in the outer rings with respect to their economic, physical, and mental well-being.

The declaration pitted residents against public health officials as debates about hazards,

risk, and responsibility erupted. Under Gibbs’s leadership, the residents mounted an effective

media campaign, staging demonstrations in Niagara Falls, Buffalo, and on the road to Albany.

With local men employed in the community’s chemical industry, women became the public face

of the protests. The movement was non-violent in nature and was focused on protecting families’

health and homes. Practicing what is now called popular epidemiology, Gibbs and the

Homeowners’ Association women surveyed their friends and neighbors and plotted the reported

illnesses geographically, in the process identifying a possible means by which the broader

neighborhood had been contaminated, contamination that had spread via local geological

features residents called “swales.” This explanation offered a causal account of contamination

that suggested that the chemicals had migrated from the landfill in a non-linear fashion, a direct

rebuff of the reasoning used by the DOH (Dept. of Health) to determine the boundary lines of

contamination. Despite this epidemiological work, public health officials maintained the safety

of the outer-ring neighborhood. But the Homeowners’ Association continued to challenge them.

Gibbs successfully led the Homeowners’ Association in framing the disaster as an attack on the

nuclear family, as the toxic contamination threatened reproduction and homes. The emphasis on

traditional family roles and the demand for safe living spaces formed the basis for a new kind of

citizenship, different from previous relationships with the state centered on economic identity or

property ownership. This approach justified relocation based on the preservation of family life

rather than on the injustice of dumping toxic waste where it disproportionately harmed minorities

and poor communities.

Another aspect of environmental justice at Love Canal can be seen in the relations

between homeowners and other residents. As the months wore on, tensions arose among

residents, most particularly between homeowners and the occupants of a public housing

development known as Griffin Manor. Of the 1100 residents living there, most received public

assistance, and 60 percent were African American. One 63-year-old black grandmother

condemned the lack of attention low-income renters had received so far during the crisis. The

woman never saw any public officials, though she was home all day. She attributed this fact to

race. “Mostly black people live in these projects, what do they care? Kill them all (laugh).”

Many Griffin Manor renters also felt abandoned by the Homeowners’ Association, whose

membership was based on home ownership. This led to the creation of a separate organization,

the Renters’ Association. From the beginning, the Renters’ Association had a different

relationship with state officials. They were assigned a liaison, but were refused the services of a

scientific consultant (something provided to the Homeowners’ Association). The misconception

18

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

that the renters could leave at any time, unburdened by their investments in property like local

homeowners, harmed the group. Poor residents had few resources to be able to move, and Griffin

Manor offered some of the only public housing in Niagara Falls with four- and five-room units

that accommodated families. While the Homeowners’ Association leadership publicly supported

the Renters’ Association, rank-and-file members were more antagonistic. Although the area also

had swales running through it, some Homeowners’ Association members argued that the

chemicals had traveled in specific directions, currents that missed contaminating Griffin Manor.

Many homeowners feared that adding several hundred renters to relocation plans would make

the cost too high, and these anxieties in part prompted the tense relations between the two

groups. Both sets of residents, however, had to deal with a public health department that

struggled to define and respond to the chemical contamination.

. . . Prompted by the question of one of his congregants who wanted to know what the church

was doing to help Love Canal residents, Presbyterian minister Paul Moore helped organize area

churches in response to the disaster early in 1979. Local religious denominations created the

Ecumenical Task Force to Address the Love Canal Disaster (ETF), providing immediate

financial and material aid to relocated residents and those still living in the area. In the process of

coping with residents’ immediate needs, the Task Force also attempted to address the larger

issues of state responsibility. Led by Sister Margeen Hoffmann, an experienced administrator

who had headed traditional disaster relief efforts, ETF members surveyed the needs of the

community and debated what role religious organizations should have. Many saw the actions of

the Task Force as fulfilling the traditional functions of faith communities—the pastoral and the

ethical—as they helped residents deal with the environmental mess and the subsequent social

disruption.

. . . President Jimmy Carter issued an emergency disaster declaration in May 1980, based not on

the physical hazards residents were exposed to, but rather on the mental distress they

experienced. Most homeowners and Griffin Manor renters were relocated by the end of 1980,

although remediation continued to pose problems for local, state, and national agencies. Many of

the homeowners moved only a few miles from the contaminated site to nearby communities, and

renters moved into other Niagara Falls public housing locations. Lois Gibbs divorced her

husband and moved her children to Falls Church, Virginia, where Michael and Missy showed no

signs of continuing ill health. In Falls Church she founded the Center for Health, Environment

and Justice, an organization dedicated to supporting grassroots anti-toxic campaigns. A quasifederal/private agency, the Love Canal Area Revitalization Agency, began rehabilitating homes

that had been built directly above the dumpsite, in what was known as the inner ring. The project

was subsidized by state monies and the homes were sold at a discounted rate, as both the city of

Niagara Falls and state of New York wanted to put the disaster to rest. State agencies, however,

refused to guarantee the safety of the area. While the surrounding neighborhoods again have

occupants, the original canal site remains fenced off as remediation activities continue. The

disaster gradually disappeared from public memory, despite being at least in part the catalyst of

the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, better

known as Superfund. The legislation allocated federal monies to remediate uncontained

hazardous waste sites. In 1995, the EPA sued Occidental Petroleum (the company that bought

Hooker Chemical) and won a $129 million settlement."

.

19

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

20

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

6 - Native American Rights

Document: The Alcatraz Proclamation to the Great White Father and His People (1969). In

1969, fourteen Native American activists (including college students) from a group called

Indians of All Tribes (IAT) occupied Alcatraz Island, in San Francisco Bay. The occupation lasted

for nineteen months, and at its peak over 400 people lived on the rock.

"We, the native Americans, re-claim the land known as Alcatraz Island in the name of all

American Indians by right of discovery. We wish to be fair and honorable in our dealings with

the Caucasian inhabitants of this land, and hereby offer the following treaty:

We will purchase said Alcatraz Island for twenty-four dollars (24) in glass beads and red

cloth, a precedent set by the white man's purchase of a similar island about 300 years ago. We

know that $24 in trade goods for these 16 acres is more than was paid when Manhattan Island

was sold, but we know that land values have risen over the years. Our offer of $1.24 per acre is

greater than the 47 cents per acre the white men are now paying the California Indians for their

land.

We will give to the inhabitants of this island a portion of the land for their own to be held

in trust by the American Indian Affairs and by the bureau of Caucasian Affairs to hold in

perpetuity--for as long as the sun shall rise and the rivers go down to the sea. We will further

guide the inhabitants in the proper way of living. We will offer them our religion, our education,

our life-ways, in order to help them achieve our level of civilization and thus raise them and all

their white brothers up from their savage and unhappy state. We offer this treaty in good faith

and wish to be fair and honorable in our dealings with all white men.

We feel that the so-called Alcatraz Island is more than suitable for an Indian Reservation,

as determined by the white man's own standards. By this we mean that this place resembles most

Indian reservations in that:

It is isolated from modern facilities, and without adequate means of transportation.

It has no fresh running water.

It has inadequate sanitation facilities.

There are no oil or mineral rights.

There is no industry and so unemployment is very great.

There are no health care facilities.

The soil is rocky and non-productive; and the land does not support game.

There are no educational facilities.

The population has always exceeded the land base.

The population has always been held as prisoners and kept dependent upon others.

Further, it would be fitting and symbolic that ships from all over the world, entering the Golden

Gate, would first see Indian land, and thus be reminded of the true history of this nation. This

tiny nation would be a symbol of the great lands once ruled by free and noble Indians."

21

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

"Occupy Wounded Knee: A 71-Day Siege and a Forgotten Civil Rights Movement", by Emily

Chertoff, The Atlantic, October 23rd, 2012.

This article appeared in The Atlantic Monthly after the death of Russell Means, one of the

leaders of AIM in the late 1960's and 1970's. Means was

On February 27, 1973, a team of 200 Oglala Lakota (Sioux) activists and members of the

American Indian Movement (AIM) seized control of a tiny town with a loaded history -Wounded Knee, South Dakota. They arrived in town at night, in a caravan of cars and trucks,

took the town's residents hostage, and demanded that the U.S. government make good on treaties

from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Within hours, police had surrounded Wounded Knee,

forming a cordon to prevent protesters from exiting and sympathizers from entering. This

marked the beginning of a 71-day siege and armed conflict. . .

. . . The Wounded Knee siege was both an inspiration to indigenous people and left-wing

activists around the country and -- according to the U.S. Marshals Service, which besieged the

town along with FBI and National Guard -- the longest-lasting "civil disorder" in 200 years of

U.S. history. Two native activists lost their lives in the conflict, and a federal agent was shot and

paralyzed. Like the Black Panthers or MEChA, AIM was a militant civil rights and identity

movement that sprung from the political and social crisis of the late 1960s, but today it is more

obscure than the latter two groups.

The Pine Ridge reservation, where Wounded Knee was located, had been in turmoil for years. To

many in the area the siege was no surprise. The Oglala Lakota who lived on the reservation faced

racism beyond its boundaries and a poorly managed tribal government within them. In particular,

they sought the removal of tribal chairman Dick Wilson, whom many Oglala living on the

reservation thought corrupt. Oglala Lakota interviewed by PBS for a documentary said Wilson

seemed to favor mixed-race, assimilated Lakota like himself -- and especially his own family

members -- over reservation residents with more traditional lifestyles. Efforts to remove Wilson

by impeaching him had failed, and so Oglala Lakota tribal leaders turned to AIM for help in

removing him by force. Their answer was to occupy Wounded Knee.

Federal marshals and National Guard traded heavy fire daily with the native activists. To break

the siege, they cut off electricity and water to the town, and attempted to prevent food and

ammunition from being passed to the occupiers. Bill Zimmerman, a sympathetic activist and

pilot from Boston, agreed to carry out a 2,000-pound food drop on the 50th day of the siege.

When the occupiers ran out of the buildings where they had been sheltering to grab the supplies,

agents opened fire on them. The first member of the occupation to die, a Cherokee, was shot by a

bullet that flew through the wall of a church.

To many observers, the standoff resembled the Wounded Knee Massacre of 1890 itself -- when a

U.S. cavalry detachment slaughtered a group of Lakota warriors who refused to disarm. Some of

the protesters also had a more current conflict in mind. As one former member of AIM told PBS,

"They were shooting machine gun fire at us, tracers coming at us at nighttime just like a war

zone. We had some Vietnam vets with us, and they said, 'Man, this is just like Vietnam.' "

When PBS interviewed federal officials later, they said that the first death in the conflict inspired

them to work harder to bring it to a close. For the Oglala Lakota, the death of tribe member

22

APUSH Unit 8

Heasman

Assignments

Buddy Lamont on April 26 was the critical moment. While members of AIM fought to keep the

occupation going, the Oglala overruled them, and, from that point, negotiations between federal

officials and the protesters began in earnest. The militants officially surrendered on May 8, and a

number of members of AIM managed to escape the town before being arrested. (Those who were

arrested, including Means, were almost all acquitted because key evidence was mishandled.)

Even after the siege officially ended, a quiet war between Dick Wilson and the traditional, proAIM faction of Oglala Lakota continued on the reservation -- this despite Wilson's re-election to

the tribal presidency in 1974. In the three years following the stand-off, Pine Ridge had the

highest per capita murder rate in the country. Two FBI agents were among the dead. The Oglala

blamed the federal government for failing to remove Wilson as tribal chairman; the U.S. retorted

that it would be illegal for them to do so, somewhat ironically citing reasons of tribal selfdetermination.

23