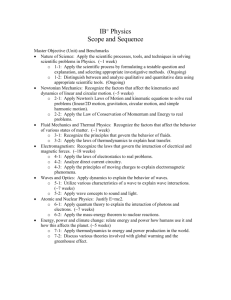

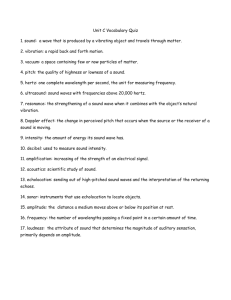

Part One

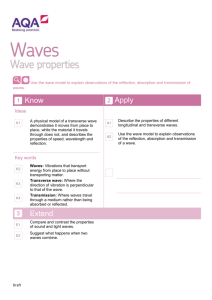

advertisement