Resident Version

advertisement

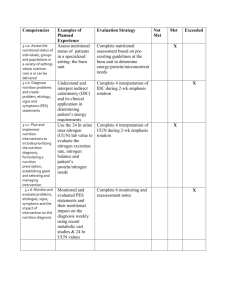

Resident Version Nutrition in Hospitalized Patient Created by Dr. Fraz Harji Updated 5/2009 Objectives: 1. 2. 3. 4. Identify three deleterious consequences of malnutrition. List three ways to assess the nutritional status of a hospitalized patient. List 3 clinical indications for initiation of artificial nutritional support. Choose appropriate route of nutrition and monitoring parameters based on a patient's clinical scenario. Reference: 1. Waitzberg, Dan L., Correia, Maria Isabel T.D. Nutritional Assessment in Hospitalized Patient. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, Vol 6 (5), September 2003, pp 531-538 2. Uptodate online, www.utdol.com, accessed July 2007, Overview of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 3. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: parenteral nutrition. Gastroenterology 2001 Oct;121(4):966-9. 4. Kirby DF, DeLegge MH, Fleming CR. American Gastroenterological Association technical review on tube feeding for enteral nutrition. Gastroenterology 1995;108:1282-1301. Discussion Outline: Importance of Nutrition Some degree of malnutrition occurs during most hospitalizations. Malnutrition in hospitalized patients can lead to a number of deleterious consequences, such as: Increased susceptibility to infection Poor wound healing Increased frequency of decubitus ulcers Overgrowth of bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract Abnormal nutrient losses through the stool Increased hospital length of stay Increased morbidity and mortality Addressing nutritional status is most important during critical illness since the body loses its ability to conserve during such stress. Identifying malnutrition early and selecting appropriate intervention can prevent these deleterious effects. I. Assessment of Nutritional Status 1. History a. History of weight loss or pre-existing malnutrition history One study showed that the accuracy of weight loss by history was 0.67 and the predictive power was 0.75. This suggests that 33% of patients who indeed had loss weight would not have been identified and 25% of patients who had stable weight would have been identified as having lost weight. b. Altered food consumption c. Gastrointestinal derangements d. Decreased functional capacity 2. Physical exam a. Muscle wasting or loss of adipose tissue b. Presence of edema or ascites c. Current BMI (Difficult to measure height in critically ill patients) 3. Laboratory assessment a. Albumin - Long half life of 14-21 days makes it less responsive to acute changes in nutritional status. - Albumin level is a reflection of a balance between hepatic synthesis, degradation and losses from the body - Levels may be altered for factors other than malnutrition. - In acute stress due to infection, surgery, and multi-trauma, albumin levels are generally very low as a consequence of decreased synthesis, increased degradation, transcapillary losses and fluid replacement. b. Prealbumin - More reliable indicator of nutritional status than albumin because its half life of 24 to 48 hours makes the plasma concentration more reflective of the current nutritional state - However prealbumin may also be altered by other situations such as hepatic or renal failure, and infection II. Indications for initiation of artificial nutritional support Preexisting nutritional deprivation. Anticipated or actual inadequate intake by mouth. For well-nourished adults, inadequate oral intake of 7-14 days. Earlier intervention is necessary in patients who are already malnourished. However the length of starvation tolerated by each patient will vary depending on previous nutritional status and reserves, and current metabolic demands. 3. Significant multiorgan system disease or critically ill patients. 1. 2. III. Route of artificial nutrition Enteral vs Parenteral Route: "If the gut works, use it." The enteral route is preferred over the parenteral route provided that there is a functional gut and there are no contraindications such as ileus, gastrointestinal ischemia, bilious or persistent vomiting, or mechanical obstruction. IV. Type of Access and Site of Administration Access can be intragastric (eg, nasogastric or gastrostomy tubes), or transpyloric (eg, nasoduodenal, nasojejunal). Intragastric feedings are generally preferred due to their more physiologic nature, but transpyloric feedings may be selected in patients at risk for aspiration. For the short-term feeding (<30 days), nasogastric or nasoenteric tubes are preferred over gastrostomy or jejunostomy tubes A. Enteral Feeding 1. Gastric Feeding a. Intragastric feeding is well tolerated by most patients. b. It is a physiological route - it can buffer gastric acid better and is able to tolerate a larger volume and osmotic load than post-pyloric feedings. c. Easy to place; Orogastric or Nasogastric tubes are relatively safe procedure and requires minimal training 2. Post-pyloric feeding a. The most common indications are: Pulmonary aspiration Severe GERD and esophagitis Recurrent emesis Post surgery/multiple trauma Gastric, antroduodenal dysmotility Patients with decreased bowel sounds and those on paralytic agents. In both settings gastric motility may be impaired more than intestinal motility. 3. Jejunal feeding a. The most common indications are: Recurrent aspiration of gastric contents Esophageal dysmotility with a history of regurgitation Delayed gastric emptying Frequency of Feeding, Tolerance and Monitoring 1. The initial feeding regimen should be dictated by the patient's clinical status. A stable patient can be started on bolus NG feeds, whereas less stable patients may be started with continuous gastric feeds. 2. Feeding tolerance must be continually assessed by monitoring stool frequency, the presence of diarrhea, abdominal distension, urinary output, and vomiting. 3. Monitoring of gastric residual volumes needs to be done frequently to assess tolerance, although a single high residual volume should not lead to unnecessary interruption of feed but should be rechecked in 1 hour. B. Parenteral Feeding 1. After literature review, and based on meta-analysis of 82 randomized controlled trials, American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) recommends parenteral nutrition may improve clinical outcomes in patients with short bowel syndrome and in post-operative patients with esophageal or gastric cancers. 2. No clear benefit in mild acute pancreatitis, acute exacerbation of IBD, chronic pulmonary disease, or AIDS. 3. Parenteral nutrition (TPN and PPN) increases catheter-associated infections and thrombosis a. Nutrition solutions should be infused into a large central vein and location of the catheter tip must be confirmed radiographically and must be documented in the medical record. b. There is risk of intimal damage from the catheter and infusate and thrombophlebitis. c. Solutions infused in a non-central catheter should be limited in osmolarity and these generally provide inadequate calories unless infused at a high rate. Review Questions: 1. A 74-year-old man is transported to the emergency department by ambulance for evaluation of cough, dyspnea, and altered mental status. Upon arrival, the patient is noted to be minimally responsive. Results of physical examination are as follows: temperature, 102.1, heart rate, 116 beats/min; blood pressure, 94/62 mm Hg; respiratory rate, 34 breaths/min; and O2 saturation, 72% on 100% O2 with a nonrebreather mask. The patient is intubated in the emergency department, and mechanical ventilation is initiated, and the patient is admitted to the medical intensive care unit for further management. The intern on call inquires about the appropriateness of initiating nutritional support (enteral or parenteral feeds) at this time. Which of the following statements regarding nutritional support is true? A. Enteral nutrition is less likely to cause infection than parenteral nutrition. B. Parenteral nutrition has consistently been shown to result in a decrease in mortality, compared with standard care C. The use of oral supplements in hospitalized elderly patients has been shown to be harmful D. Parenteral nutrition is the preferred mode of nutrition in cancer patients because of its lower incidence of infections 2. A 64-year-old man with a long history of poorly controlled diabetes is diagnosed as having gastroparesis on the basis of his medical history and transit tests showing delayed gastric emptying. He is referred to you for long-term treatment. Which of the following should NOT be included in your treatment strategy? E. F. G. H. Correction of dehydration and electrolyte and nutritional deficiencies Pro-kinetic therapy with metoclopramide or erythromycin Vagotomy Anti-emetics as needed Answer: C Concept: To know the major modalities used in the treatment of gastroparesis The major treatment approaches for the patient with a gastric or small bowel motility disorder include correction of fluid, electrolyte, and nutritional deficiencies; the use of pro-kinetic agents such as metoclopramide and erythromycin; the use of anti-emetic agents for symptomatic relief; suppression of bacterial overgrowth (if present); decompression in severe cases; and surgical resection if the disorder is determined to be isolated to one discrete area of the gut. Vagotomy can actually cause gastroparesis and should be avoided. 3. A 38-year-old man with debilitating Crohn's disease who is status post a 40 cm ileal resection presents for evaluation. He recounts progressive non-bloody diarrhea since his surgery 9 months ago, which is worse in the evening. He denies having abdominal pain, nausea or vomiting, fevers, chills, or sweats. He reports no recent travel, camping, or use of antibiotics. The exam is unrevealing. Chemistries show modest hypokalemia and mild non-anion gap acidosis. Fecal fat quantitative analysis reveals minimal steatorrhea. Which therapy is most likely to help this patient? A. B. C. D. E. Cholestyramine Loperamide Tetracycline High-protein, low-fat diet Safflower oil before meals 4. A 32-year-old man with AIDS who is experiencing chronic diarrhea, anorexia, and wasting is referred for evaluation for nutritional support. Results of physical examination are as follows: temperature, 97.6 F; heart rate, 67 beats/min; blood pressure, 102/62 mm HG; respiratory rate, 12 breaths/min; height, 70 in; and weight, 50 kg. The patient appears chronically ill; there is bitemporal wasting, and his hair is easily pluckable. The patient says he has friends with AIDS who are receiving “I.V. nutrition,” and he would like to know if such therapy would benefit him. Which of the following statements regarding home total parenteral nutrition (TPN) is true? I. Evidence demonstrates improved survival and quality of life in patients with metastatic cancer who are receiving home TPN. J. Evidence demonstrates improved survival and quality of life in patients with AIDS who are receiving home TPN K. Evidence demonstrates improved survival and quality of life in patients with short bowel from Crohn disease who are receiving home TPN L. No evidence supports the use of home TPN in any patient population CASE You are consulted by the orthopaedic physician to evaluate a 96 yo female, s/p hip fracture and subsequent ORIF 1 week ago, for management of diabetes and hypoglycemic episodes. You find that patient has been placed on her regular outpatient medications for diabetes which includes Lantus 10 units SQ qam and a regular sliding scale insulin. Her cbg’s for the past few days have been fluctuating between 40 and 150. You proceed to patient’s bedside and find a very thin elderly woman who appears to be sleeping/sedated on her morphine pca; she is arousable, but falls back asleep quickly. Patient’s family indicates that patient has been suffering from a lot of pain and the pca pump is helping manage it. You also note a physical therapy note which indicates that patient is weak, groggy and in pain, unable to participate in therapy most days. Family is concerned that patient is weak and not going to make it and asks you for help. With regards to her diabetes, they tell you that that the patient has been taking this current amount of Lantus for the past several years without adverse effects and don’t understand why she is getting low blood sugars now. 1. What is your differential for her hypoglycemic episodes? 2. How would you like to adjust her insulin? 3. What do you think is her current amount of oral intake and how can you assess that over the next few days? 4. What should you do about her pain control and her sedated state? 5. What is the nutritional status of this hospitalized patient provided by the information above? 6. What lab would be helpful to assess her past and current nutritional status? 7. Does this patient have indications for initiation of artificial nutritional support? 8. What would be most appropriate route of nutrition in this patient, enteral or parenteral nutrition? 9. Should the patient be allowed to eat or remain NPO while she receives tube feeding? Post Module Evaluation Please place completed evaluation in an interdepartmental mail envelope and address to Dr. Wendy Gerstein, Department of Medicine, VAMC (111). 1) Topic of module:__________________________ 2) On a scale of 1-5, how effective was this module for learning this topic? _________ (1= not effective at all, 5 = extremely effective) 3) Were there any obvious errors, confusing data, or omissions? Please list/comment below: ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ 4) Was the attending involved in the teaching of this module? Yes/no (please circle). 5) Please provide any further comments/feedback about this module, or the inpatient curriculum in general: 6) Please circle one: Attending Resident (R2/R3) Intern Medical student