miranda.R

advertisement

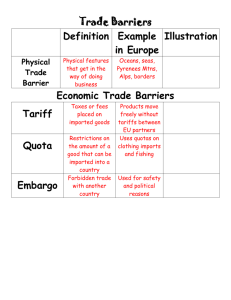

Colloque du Réseau Intégration Nord Sud (RINOS) Montréal, 1-3 juin 2005 Organisé conjointement avec le Centre Études Internationales et Mondialisation (CEIM) Université du Québec à Montréal INTÉGRATIONS RÉGIONALES ET STRATÉGIES DE DÉVELOPPEMENT : Les relations Nord-Sud dans l’Euromed, les Amériques et l’Asie. The Mercosur– European Union Free Trade Agreement: an estimate of the impacts on Brazilian foreign trade Honorio Kume1 Guida Piani2 Pedro Miranda3 Marta Castilho4 1. INTRODUCTION The Mercosur and the European Union (EU) have been negotiating a free trade agreement since mid 1990’s. After some years of discussions on the methods and procedures for the negotiations—which lasted longer than anticipated—proposals started to be presented in 2001. In July 2001, the UE made an offer covering trade in goods, with a schedule for the elimination of tariffs, as well as trade in services and government procurement. At that moment, additional quotas for agricultural products were not included, as the Europeans argued that they should be used to encourage further liberalization (Castilho, 2003). A final and more elaborated proposal was presented in May 2004. The EU offer included 90% of the total tradeable goods, classified into five groups, four of which with linear liberalization schedules from zero to ten years. Furthermore, bilateral tariffs on a group of products – basically information technology, pharmaceuticals and chemicals goods - should immediately be brought down to zero, and reciprocal concessions should be made in textiles, clothing and footwear. As to agricultural processed goods, additional quotas were offered with reduced in-quota tariffs for most of Mercosur exports: bovine, poultry and swine meat, ethanol, and corn. For others products, it mentioned only the concession of future additional quotas, with no volume specification. From Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada – IPEA and Universidade do Estado do Rio de Janeiro – UERJ. e-mail: kume@ipea.gov.br 2 From Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica e Aplicada – IPEA. e-mail: guidapiani@ipea.gov.br 3 From Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica e Aplicada – IPEA and Universidade Federal Fluminense – UFF. e-mail: pmiranda@ipea.gov.br 4 From Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica e Aplicada – IPEA and Universidade Federal Fluminense – UFF. e-mail: castilho@ipea.gov.br 1 On the other hand, the Mercosur countries improved their previous offer on goods, increasing the coverage of products from 87.8% up to 90% of total tradeable goods, by incorporating textiles and steel products. Major concessions were also made in services. Afterwards, the negotiations were intensified, and the parties exchanged new offers in September 2004, hopping to reach an agreement in late October, before the change of European Commission ministers. However, the fell far away short of the expectations of both sides and the negotiations were suspended. Indeed, the proposals presented by the Mercosur and the European Union in September reflected an atmosphere of deterioration in the negotiations with mutual accusations of important setbacks in the conditions of liberalization offered before. The purpose of this paper is to assess the impacts of an hypothetical agreement based on the best offer – the one presented in May 2004 - specifically on trade flows between Brazil and the EU, using a partial equilibrium model. The following estimates consider not only the gains associated with the tariff reductions but also those resulting from additional quotas with preferential treatment and the gains from the appropriation of quota rents by the Brazilian exporters of processed agricultural products. This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 details the most relevant aspects of the liberalization programs presented by the European and South American countries in May 2004 and also points out the importance of trade between them on a product category basis. Section 3 summarizes the methodological procedures and sources of data used to calculate estimates for Brazil and the EU, while the results are presented and commented in Section 4. The conclusions are presented in Section 5. 2. THE EU AND MERCOSUR TRADE LIBERALIZATION PROPOSALS 2.1 A BRIEF HISTORY In 1994, the EU, under the Spanish presidency, signaled the intention to establish an interregional association with the Mercosur. The proposed agreement had three axes: a commercial one, which aimed at forming a free trade area, another one about economic cooperation, and that of a greater political understanding. The European Commission made it clear form the very beginning that the agricultural products would not be given a special treatment, as they described the trade agreement as the “progressive establishment of a free trade zone in the industrial and services areas as well as a reciprocal and progressive liberalization of agricultural trade, considering the sensitivity of certain products” (European Commission, 1994). After the signing of the document of in 1994, the project has gone through periods of both major and minor enthusiasm. The study phase, scheduled to last until 1997, was extended, mostly because of the lack of the EU interest in advancing the negotiations. Talks were resumed in June 1999, when the Rio de Janeiro summit took place. As of then, the process gained a little more consistency and automaticity with the institution of the Committee of Bi-regional Negotiations. Three technical groups were established to deal with trade issues: a) customs issues related to trade in goods (tariffs, non-tariff barriers, technical standards, rules of origin, and antidumping law); b) trade in services, intellectual property, and investment related measures; and c) government procurement, competition and dispute resolution. Towards the end of that same year, representatives from both parties met again and decided that information exchanges would go on through June 2000. The following phase — that of exchanging papers — lasted until July 2001, when the methodology and the schedule for liberalization of goods and services were defined. 2 In June 2001, the EU unilaterally presented a list of products for negotiation. This initiative proved to be rather positive, as the Mercosur countries were facing difficulties to define common positions, due to the macroeconomic problems faced mostly by Argentina, at that moment. From that point on, various versions of offers from both sides were exchanged: a second one in 2003 and another two in 2004. In 2003, it was decided that negotiations would be intensified in the following year so that an agreement could be signed before the end of the mandate of the current European Commission team. Negotiations were indeed very intense: two formal offers were exchanged, other informal consultations were made, but no final agreement was reached. Therefore, negotiations remained inconclusive but with some additional difficulties related to the enlargement of the European Union and new members’ resistance to commercially opening up to the Mercosur. 2.2 THE MERCOSUR PROPOSAL The Mercosur May 2004 proposal defines five categories of products with different timeframes for liberalization (Table 1). Besides those, a group of products with a constant 20% margin of preference and another one without any definition of a liberalization schedule were included at the last moment. So, for instance, the products included in category A would have full liberalization immediately while those with fixed preference would have a mere 20% reduction without ever reaching the free trade status. TABLE 1 TARIFF REDUCTION SCHEDULE PROPOSED BY THE MERCOSUR, BY PRODUCT CATEGORY (in %) Category/year 0 A 100 B 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 50 50 100 C 11 22 D 0 E Fixed preference 9 10 33 44 55 66 77 88 100 10 15 25 30 40 50 60 70 85 100 0 0 10 15 25 35 45 55 70 85 100 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 Not defined Source: Department of International Negotiations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Table 2 shows the number of products classified in each category, according to the 8-digit classification of the Mercosur Common Nomenclature-Harmonized System (MCN-HS8), the common external tariff (simple average) for each category, and the share of Mercosur total imports from the EU in the 2001-2003 period. The products for which an extended period of protection was scheduled—classified in categories D and E— represent about 50% of the total and 27% of the Mercosur imports from the EU in the 2001-2003 period. Manufactured products are concentrated there. For instance, most textile, clothing and footwear, as well as automobiles, are in category E. A considerable part of machinery and equipment is also classified in these two categories, though less concentrated than the previous products. 3 TABLE 2 NUMBER OF PRODUCTS, AVERAGE TARIFF, AND SHARE OF MERCOSUR IMPORTS, BY PRODUCT CATEGORY – 2001/2003 Category Number of products HS8 (%) Average tariff Imports (%) A 657 6.7 0.0 14.4 B 1,801 18.5 2.1 5.2 C 1,433 14.7 8.3 46.4 D 1,975 20.3 13.4 6.7 E 2,905 29.8 16.5 20.0 Fixed preference 79 0.8 15.7 0.4 Not defined 880 9.0 15.5 6.8 9,730 100.0 10.8 100.0 Total Source: Department of International Negotiations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Author’s calculations. At the other extreme, immediate liberalization is scheduled for only 657 products, which comprehend 14.4% of imports from the EU. However not significant in volume of trade, category B includes a large number of products. Category C is the one concentrating most imports. In these categories, there are agricultural and food products, besides some mineral ones. Still, considering the trade volume, category C is much more important than the previous two. For 79 products, mostly food products, a 20% margin of preference has been offered. The average external tariff for these products is almost as high (15.7%) as that for category E products (16.5%) and virtually equal to that of the group of 880 products (15.5%) for which no concession was made. 2.3 THE EUROPEAN PROPOSAL The first EU 2001 offer covered trade in goods, services and government procurement. Besides containing a schedule for the elimination of tariffs, it also included other trade related disciplines, such as antidumping code, safeguard measures, custom valuation, and sanitary and phytosanitary measures—the latter to be dealt within the framework of the World Trade Organization agreements—, national treatment and the extinction of export/import prohibitions and restrictions. Evidently, this last point would not be applied to tariff-rate quotas for certain agricultural products, which might wait for further incorporation in the proposal to be presented in 2004. Three sectors should enjoy special treatment in the agreement. Wines and other alcoholic beverages should be the object of a special agreement and the concessions for textiles and footwear should be subject to “strict reciprocity”.5 The initial proposal for the liberalization of trade in goods created five product categories: four with a schedule up to ten years (A, B, C and D) and another one covering goods for which liberalization was not 5. It is worth pointing out that the EU is negotiating with Brazil a bilateral agreement for the liberalization of trade in textile products, by which increased quotas for Brazilian products are being anticipated. Argentina already has a bilateral agreement with the EU. 4 foreseen (E). Notwithstanding, as negotiations evolved, the EU added new categories, composed of products previously included in category E. In these categories, the products would receive fixed margins of preference of 25% and 50% and additional tariff-rate quotas with a 50% margin of preference, with amounts varying according to the good (Table 3). TABLE 3 TARIFF REDUCTION SCHEDULE PROPOSED BY THE EU, BY PRODUCT CATEGORY (in %) Category/year 0 1 2 3 4 A 100 B 5 6 7 20 40 60 80 100 C 12.5 25 37.5 50 D 9 18 27 E 0 0 Fixed preference 25 Fixed preference 50 8 9 10 62.5 75 87.5 100 36 45 54 63 72 81 90 100 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 25 50 50 50 50 50 50 50 50 50 50 Additional tariff-rate quota (variable) Not defined Source: European Commission. Comparing to the 2001 version, the European May 2004 offer incorporated some improvements—the total coverage of negotiated products increased [from 9,165 in the EU 8-digit Combined Nomenclature (NC8) to 10,427], and some products were added to category A (from 2,998 to 4,323 tariff lines). However, the products included in E rose from 195 to 410. Category A is the one with the greatest number of products (NC8)—70% of total imports. However, the tariff protection imposed to these products is rather weak and 50% of them already enjoy free access to the European market. Categories B and C comprise a high number of products, representing about 19.1% of EU imports from the Mercosur in the 1998-2000 period. Category E plus those created afterwards, including products with respectively 25% to 50% margins of preference, and processed agricultural goods, to which tariff-rate quotas were offered, consist of 809 products and about 6% of total imports. However, these products’ reduced weight in trade today already result from the effects of the protection that currently discriminates against European imports. Specific tariffs—usually an indicator of high levels of protection— apply to 404 out of the 410 products in category E, to all of those that are subject to tariff-rate quotas, and to respectively 100% and 90% of those with 25% and 50% margins of preference (Table 4). 5 TABLE 4 NUMBER OF PRODUCTS, AVERAGE TARIFF, AND SHARE OF EU IMPORTS, BY PRODUCT CATEGORY Category Number of products NC8 (%) Average ad valorem tariff Number of products — specific tariff Imports (%) A 4,323 41.5 1.4 8 69.9 B 2,182 20.9 4.5 46 6.7 C 2,664 25.5 8.4 59 12.4 D 429 4.1 17.0 99 5.0 E 410 3.9 15.1 404 0.1 Fixed preference 25% 22 0.2 7.5 22 0.0 Fixed preference 50% 100 1.0 22.1 90 2.1 Additional tariff-rate quota 277 2.7 10.6 277 3.8 Not defined 21 0.2 3.0 20 0.0 10,427 100.0 4.9 1,025 100.0 Total Source: Department of International Negotiations, Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Author’s calculations. For some products, the EU made a two-stage offer of additional tariff-rate quotas (with preference margin of 50% of the in-quota tariff): the first one to be delivered immediately and the second one after the completion of the Doha Round. However, the amount of the second portion will be conditioned by the results of this Round, and may increase or decrease depending on the agricultural concessions that might be made by the EU.6 Despite some of the proposed additional tariff-rate quotas’ being inferior to the volumes actually exported by the Mercosur, European negotiators argue that additional exports may be generated by this offer, because the tariff reduction would provide resources to reduce prices, thus increasing Mercosur competitiveness. 2.4 THE BRAZILIAN — EU TRADE BALANCE Though the negotiations for a free trade agreement do take place between the Mercosur and the EU, the purpose of this paper is to assess its implications on the Brazilian trade. Therefore, the following analysis will be restricted to the evolution of trade between Brazil and the EU, in the 1985-2003 period. The economic relations between Brazil—and also its Mercosur partners—with Western European countries have always been rather intense, due to historical and cultural reasons. Grilli (1993) points out that the economic complementary aspects of both groups of countries give ground to anticipate strong potential trade between them. Nevertheless, a process of gradual loosening of ties has been observed in the past few decades.7 6. For example, any commitments made by the EU to increase third countries access to its agrofood market in the Doha Round will imply smaller additional quotas for the Mercosur countries. 7. On the Latin American side, the import substitution policies, as well as the later problems of foreign debt and macroeconomic stabilization have contributed to reducing bilateral exchange; on the European side, an important option towards preferential relations with former African colonies and Eastern European countries was registered. On the other side, the European have been very cautions about approaching Latin America for fear of jeopardizing its relationship with former colonies. This position was reinforced when Spain and Portugal joined the European Community (current EU) in 6 However, the recent evolution of bilateral trade has shown a trend towards growth. As of the early 1990’s, Brazilian imports from the EU, always undercut by its exports until then, have increased vigorously. Brazilian imports moved up from US$ 5 billion in 1991-1992 to about US$ 13 billion in 2003, reaching the highest values in 1998 (over US$ 17 billion). On the other hand, Brazilian exports have grown at more moderate rates in the 1985-2003 period, reaching US$ 18 billion in 2003, reaching a surplus in trade balance again after 2000 (Chart 1). CHART 1 BRAZIL – EU TRADE, 1985-2003 (US$ billion) 20,000 16,000 12,000 8,000 4,000 Exports 20 03 20 01 19 99 19 97 19 95 19 93 19 91 19 89 19 87 19 85 0 Imports As for its composition, the trade between Brazil and the EU shows a typical North-South trade profile: Brazil exports basically primary products and by-products—56.1% of total sales correspond to sections I to IV of the Harmonized System—while its imports are mostly manufactured goods—28.5% of the total are chemical products, plastics and rubbers (sections VI and VII) and 53.5% of the total are capital goods (sections XVI to XVIII). (Table 5) 1986, when preferential commercial treatment was not extended for the first time to the former colonies of new member countries. Though the author does not include it, the major factor limiting an increase in trade flows between both parties was the European agricultural policy, which prevents further exploring of Mercosur’s natural comparative advantages, which also restricts its imports. 7 TABLE 5 COMPOSITION OF BRAZIL - EU EXPORTS AND IMPORTS — 2002 (in %) Section Description Exports I Animals and animal products II Vegetable products III Animal or vegetable fats, oils and waxes IV Imports 6.8 0.4 18.1 1.1 0.1 0.4 Foodstuff, beverages and tobacco 20.7 1.5 V Mineral products 10.4 2.7 VI Chemicals or allied industries products 4.2 22.3 VII Plastics and rubbers 1.6 6.2 VIII Hides, Skins, Leathers and articles 3.0 0.2 IX Wood and articles 3.5 0.1 X Pulp of wood, paper and paperboard 4.4 1.8 XI Textiles and textiles articles 1.4 1.3 XII Footwear, headgear and umbrellas 1.3 0.0 XIII Articles of stone, ceramic and glasses 1.1 1.2 XIV Pearls, precious metals and stones 1.1 0.4 XV Base metals and articles 8.6 6.2 XVI Machinery and electrical equipment 8.5 37.7 XVII Transport equipment 3.4 11.0 XVIII Precision Instruments 0.4 4.8 XIX Arms and ammunitions 0.0 0.0 XX Miscellaneous 1.3 0.8 100.0 100.0 Total Source: Secretary of Foreign Trade, Ministry of Development, Industry and Foreign Trade (Secex/MDIC). Author’s calculations. 3. METHODOLOGY AND DATA SOURCES 3.1 METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES The EU offer differs according to the groups of products. A first group, consisting mostly of manufactured products, would benefit from tariff reductions. For a second one, composed of agricultural products, an improvement in market assess would result from additional tariff-rate quotas, with the possibility of a discount in the preferential tariff. The Mercosur offer, instead, was concentrated only in tariff reductions. It was therefore necessary to use two distinct methodologies with the same hypotheses concerning supply and demand conditions for the products under analysis. 3.1.1 METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES – Tariff reductions In order to assess the trade gains being generated by the tariff reductions proposed by both parties, it was chosen a computable partial equilibrium model, as it is often adopted in similar exercises (Cline et alii, 1978; and Laird and Yeats, 1986). This model usually assumes that the products are differentiated according to the supplying country and, based on the usual export supply and import demand equations, the algebra expressions are derived to estimate the trade impacts. These effects may be divided into two parts. The first one, called “trade creation”, corresponds to the increased imports from the partner country in substitution of relatively inefficient internal production, and is expressed as follows: 8 CCi = MPi . Emi . (PPi/PRMi) [1 – (Emi/Exi)] where: CCi = trade creation of product i; Mpi = value of imports of product i, from a partner country, in the base-year; Emi = import price-elasticity of product i; Exi = export price-elasticity of product i. PPi = price of imports from a partner country and PRMi = price of imports from the rest of the world. Assuming that the export price-elasticity is infinite, the equation of trade creation takes the form: CCi = MPi . Emi . (PPi/PRMi) This expression means that the tariff reduction entails a variation in price [(PPi/PRMi) = ti/(1 + ti)], which, multiplied by the import price-elasticity and the value of imports in the base-year, provides the change in imports. The second part, known as “trade diversion”, measures the increase in imports from the partner country, replacing imports from the rest of the world at higher prices. It can be represented as follows (supposing infinite export elasticity as well): DCi = MPi . MRmi . ESi .(PPi/PRMi)/[MPi + MRMi + MPi . ESi .(PPi/PRMi)] where, besides the variables defined above: DCi = trade diversion of product i; MRMi = value of imports of product i from the rest of the world; Esi = elasticity of substitution; Despite the greater complexity of the expression, its interpretation is rather simple too: reducing the tariff on products coming from partner countries changes the relative price concerning imports from the rest of the world, which, multiplied by the elasticity of substitution and considering the proportion of imports from partners and suppliers from the rest of the world, triggers a change in favor of imports from partners. Thus, the total impact of liberalizing imports may be measured as: Mi = CCi + DCi 3.1.2 METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES – Tariff-rate quotas In the case of products subjected to tariff-rate quotas, the impact of offering an additional volume to be imported with a margin of preference may be analyzed using the import demand curve, the two-step supply curve—one level corresponding to the tariff-rate quota, within which the tariff is lower, and the other that represents the over-quota offer, where the tariff is higher. Furthermore, information on the international price of the product and the volume of import determined by the tariff-rate quota is required (Skully, 2001). 9 Chart 2 depicts this situation. It shows an initial situation 8, where the supply curve is given by the constant marginal cost and over-quota imports take place. Exports reach QX, where QT is within the tariff-rate quota and the remainder sales in the over-quota. Up to the fulfilling of the tariff-rate quota, exports are charged with the in-quota tariff, so the price reaches P(1 + tin). However, given the prevailing over-quota demand, domestic (European) market price reaches P(1 + tover), generating a “quota rent”. Its appropriation depends on the rules of administration of the tariff-rate quota and the market structure. Over-quota exports pay the overquota tariff, providing the import country government with a tariff revenue, besides the one generated by the in-quota tariff revenue. CHART 2 TARIFF-RATE QUOTA WITH OVER-QUOTA IMPORTS Pd P(1 + tover) Quota rent P(1 + tin) Over-quota tariff revenue D In-quota tariff revenue P CMg QT QX Imports Chart 3 presents the situation in which the importing country concedes a preferential tariff-rate quota (QA), with a margin of preference that may be, for instance, 50% of the in-quota tariff. With this offer, part of the previous over-quota imports will now benefit from the new tariff-rate quota. In the final situation, additional imports within the preferential tariff-rate quota will generate an additional rent9, equivalent to 50% of the preferential quota rent.10 The volume of imports remains, however, unchanged. The advantage for the country (Brazil) that is benefited with the additional tariff-rate quota is only due to the appropriation of part of the rent generated by the preferential tariff-rate quota, depending on the way it is administrated. 8. In this example, one may assume that this is about EU imports of a product exported by Brazil. 9. It is important to point out that, concerning the foreign currency revenue, the “quota rent” and the export revenue are equivalent to each other. However, one should also remember that exports lead to a lesser net gain for the country, insofar the costs of the production factors used in producing the exportable good are positive, whereas the “quota rent” represents an appropriation of external resources, with no production costs. 10 For lack of information about the rule of appropriation of the quota rent, it was assumed that the exporters’ share is 50%. 10 CHART 3 IMPACT OF AN ADDITIONAL TARIFF-RATE QUOTA Pd P(1 + tover) Quota rent P(1 + tin) In-quota tariff revenue Preferential quota rent D P CMg QT QT+QA M Imports The expression used to estimate the additional tariff-rate quota rent (RQ) is given by: RQ = P. QTA[tover – (tin/2)]/2 where the symbols have been previously defined. It is worth emphasizing that the exporter will not use the “additional quota rent” to increase sales. If the demand curve has a negative slope, additional exports will trigger a price drop, in such a way that the net price (over-quota tariff discounted from the price) received by the exporter will be less than the marginal cost. Therefore, there will be no incentive to increase exports – an argument used by the European negociators. A different procedure was adopted for two specific products. Since Brazilian swine meat exports to the EU are null due to sanitary restrictions, the future Brazilian exports were estimated to match the quota offer, once sanitary barriers are removed. For ethanol, the change in European environmental legislation must lead to a significant rise in the demand so that the quota offer will allow for an increase that may be identical to the export quantity. Thus, the gain for these products is the result of appropriating part of the quota rent (50%, as expressed above) and part of the increased exports (called export gain in Table 6). 3.2 PARAMETERS USED AND DATA SOURCES The import data samples in both directions have taken into account their importance in trade flows, classified by 8 digits in EU’s CN and the MCN. As a first selection criteria, product import levels above US$ 5 million and US$ 2 million were fixed, respectively, for Brazilian and the EU sales. Then, products with import tariffs below 3% have been excluded. 11 These two criteria have led to a sample of 184 products imported by the EU from Brazil, an equivalent to approximately 90% of all this import flow in 2002. For the Brazilian imports from the EU, the result was a set of 925 products, representing 61% of Brazilian imports from the European countries. In order to measure the impact of the liberalization upon the domestic price of an imported product, there have been used the tariffs effectively paid11 for Brazilian imports from the EU and the (ad valorem and specific) tariffs applied by the EU, as indicated in its own proposal, deducting the margins of preference granted in the General System of Preferences. Finaly, the following parameters were used to reflect import sensitivity in relation to price changes: for Brazil, 1.9 for the import price-elasticity for capital goods, 2 for intermediary goods, 2.9 for durable consumer goods, 1.4 for non-durable consumer goods, and 0.6 for oils and fuels (Carvalho and Parente, 1999), and average elasticity of substitution of 1.07, varying from 0.15 to 5.3 (Tourinho, Kume and Pedroso, 2003), and, for the EU, price-elasticity varying from 0.4 to 3.25 (Hoeckman, Ng and Olarreaga, 2002), and average elasticity of substitution of 1.18, varying from 0.53 to 4.83 (Gallaway, McDaniel and Rivera, 2003). As to the export-supply elasticity, there is very scarce information in the literature. By and large, infinite elasticity is used or arbitrary values are chosen, such as 0.5 (Hoeckman, Ng and Olarreaga, 2002). In this study, infinite elasticity was assumed for all products. This is a reasonable hypothesis when the import demand increase is small, compared to the total production of the offering country. Thus, concerning Brazilian imports from the EU, this hypothesis is not likely to introduce a bias into the results. However, it is possible that, for products with a high Brazilian share in the world market, the result obtained for Brazilian exports may be overestimated. For tariff-rate quota products, it was assumed a constant marginal cost, besides the following additional information: price and quantity of the product exported by Brazil, total quantity imported by the EU, in-quota tariff, volume of tariff-rate quota, and volume of the additional tariff-rate quota offered and a 50% margin of preference for the in-quota tariff. Trade data were obtained from the World Integrated Trade Solutions – WITS (World Bank), from Secex/MDIC, from the Ministry of Finance’s Federal Revenue Secretariat (SRF/MF), and those on customs tariff by the European Commission and the SRF/MF. 4. RESULTS Table 6 contains the gain estimates for Brazil due to the zeroing of tariffs for manufactured goods imported by the EU (excepting products that enjoy fixed tariff preferences), as well as those generated by the concession of additional tariff-rate quotas for agroindustry processed products.12 The estimated gains for agricultural and products from the agroindustry represent 78.6% of total gains—US$ 709 million out of a total of US$ 903 million. Approximately half of this value is accounted for a single product: ethanol. The explanation for this result comes from the magnitude of the EU offer: two tariff-rate quotas of 500 thousand tons each. 11. Imports with tariff reduction, usually to 0%, by special tax regimes—drawback, Duty Free Zone of Manaus, automotive regime, and industrial outposts—are not subject to any quantitative limitation. So, EU exports that may be favored by a tariff reduction are those exclusively subject to total payment of import taxes in Brazil. 12 Intervals for the values estimated have not been calculated due to the lack of information on the standard deviation of the elasticities used. 12 TABLE 6 BRAZILIAN EXPORTS (2002) AND ESTIMATES OF GAINS FOR BRAZIL (US$ 1,000), YEAR 10 Gains with additional tariff-rate quotas Description Export 2002 Quota rent 1st stage 1. Primary and processed agricultural goods Export gains 2nd stage 1st portion 2nd stage 177,067 175,938 Gains with tariff reduction Value % 709,253 78.6 2,507,713 85,901 77,253 1.1 Bovine meat 361,609 36,095 36,095 72,190 8.0 1.2 Poultry meat 468,002 17,980 17,980 35,960 4.0 1.3 Ethanol 15,303 18,640 18,640 377,868 41.9 1.4 Corn 43,700 5,492 4,119 9,611 1.1 1.5 Tobacco 170,294 193,094 Total estimated gains 170,294 319,648 21,405 21,405 2.4 1.6 Other meats 26,019 2,534 2,534 0.3 1.7 Banana 16,057 7,191 0.8 7,191 1.8 Fruits 173,159 16,016 16,016 1.8 1.9 Processed meat 267,500 45,454 45,454 5.0 1.10 Orange juice and others 644,281 91,967 91,967 10.2 13,340 1.5 1.11 Swine meat 1.12 Others 0 503 419 6,773 5,644 157,132 15,718 15,718 1.7 1,905,111 193,532 193,532 21.4 265,309 53,981 53,981 6.0 80,856 18,086 18,086 2.0 2.3 Footwear 172,854 36,333 36,333 4.0 2.4 Aluminum 331,111 27,931 27,931 3.1 2.5 Vehicles and parts 245,211 21,653 21,653 2.4 2.6 Others 809,770 35,548 35,548 3.9 100.0 2. Manufatured 2.1 Wood 2.2 Textile and clothing Total 4,412,824 Total, excluding ethanol 85,901 77,253 177,067 175,938 386,626 902,785 67,261 58,613 6,773 5,644 386,626 524,917 Total, excluding 2nd stage 85,901 177,067 386,626 649,594 Total, excluding 2nd stage and ethanol 67,261 6,773 386,626 460,660 Source: WITS. Author’s calculations. On the other hand, concessions made to poultry and bovine meat have proven not to be very significant. In both cases, this can be attributed to the small amount of the tariff-rate quotas to which Brazil was entitled to in 2002, with reduced tariff rates, and to the small volume offered by the EU in the current negotiations. The 13 two-stage offers of 50,000 tons each for bovine meat 13 virtually correspond to the Brazilian over-quota exports in 2002, which means an increase in dollar revenues but not in exported quantities. Tariff-rate quotas proposed for poultry meat are relatively small, when compared to the Brazilian exports to the European market. The small growth in the exports of manufactured goods was already expected, since import tariffs in force for these products are already low, both those consolidated at the WTO by the EU and those undergoing reductions within the General System of Preferences. Estimates of the EU gains, presented in Table 7, confirm previous expectations: a very high concentration on industrialized products, particularly machinery and mechanical appliances, electrical and electronic equipment, and transport equipment. This group of products accounts for more than 73% of total gains, evaluated at US$ 1.3 billion. TABLE 7 EU EXPORTS (2002) AND ESTIMATES OF GAINS FOR THE EU (US$ 1,000), YEAR 10 Sectors Export-2002 Export gain % 1. Capital goods 4,043,424 714,909 53.9 1.1 Machinery and mechanical appliances 2,455,620 477,374 36.0 1.2 Electrical and electronic machinery and equipment 1,233,104 150,947 11.4 354,700 86,588 6.5 1,004,008 262,990 19.8 2.1 Vehicles 198,558 133,698 10.1 2.2 Vehicles parts 762,261 121,922 9.2 43,189 7,371 0.6 1,059,481 95,464 7.2 4. Steel and non-ferrous metals products and tools 520,390 77,304 5.8 5. Plastics and rubbers 504,954 59,338 4.5 6. Others 679,867 115,582 8.7 7,812,123 1,325,588 100.0 1.3 Precision, optical and photographic instruments 2. Transport equipment 2.3 Railway, tramway aircraft, boats, and parts 3. Chemicals Total Source: SRF/MF. Author’s calculations. 5. CONCLUSIONS There is no economic justification for the idea that a free trade agreement should produce an equitable balance of gains for both parties, but it would rather envisage the exploitation of comparative advantages, leading the economies to greater specialization and to a more efficient allocation of their resources. So the results indicating that the gains accruing to the EU are 47% greater than that possibly obtained by the Mercosur countries should not be considered undesirable or unexpected. However, the previous analysis clearly indicates an imbalance caused, essentially, by insufficient liberalization of the agribusiness sector on the part of the EU. The most negative aspects implied by the EU proposal for Brazilian export interests are: 13. For the tariff-rate quota products, the additional quota offered by the EU to Brazil was calculated according to the Brazilian share in Mercosur exports to the EU, in 2002. 14 a) approximately half of the gains for agrofood products are concentrated on a single product, ethanol, due to the high tariff-rate quotas being offered. However, to come true, these concessions would depend on a future demand for the product in the EU, which will have to be supplied basically by imports; b) gain estimates for Brazilian exports of bovine and poultry meat are inexpressive. For the former, tariff-rate quotas offered correspond to actual Brazilian over-quota exports in 2002. Therefore, the potential gains would come only from the additional quota rents; and c) important products of the agrobusiness industry were not specifically included, such as sugar. The limited offers made by the EU to Brazilian primary agrobusiness products remain as an impediment to a successful match between the Mercosur and EU economic comparative advantages. Indeed, the results obtained here for Brazil and the EU suggest that the basic principles of a free trade agreement are at stake. Concerning goods, the negotiations point to distinct directions: one of a rather comprehensive liberalization for industrialized products, and another of a rather restricted liberalization for agribusiness products. This imbalance would probably worsen if the services sector had been included in this analysis. 15 Bibliography CARVALHO, A., PARENTE, A. Impactos comerciais da área de livre-comércio das Américas. Brasília: IPEA, March 1999 (Working Paper, 635). CASTILHO, M. Acordo Mercosul-União Européia: perspectivas das exportações de manufaturados para o mercado europeu. In: MARCONINI, M., FLORES, R. (publishers). Acordo Mercosul-União Européia: além da agricultura. Rio de Janeiro: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, 2003. CLINE, R. W. et alii. Trade negotiations in the Tokyo Round: a quantitative assessment. Washington, D.C.: Brooking Institution, 1978. COMISSÃO EUROPÉIA. Pour un renforcement de la politique de l’Union Européenne à l’égard du MERCOSUR. Communication de la Commission au Conseil et au Parlement Européen, Bruxelas, 1994. GALLAWAY, M., McDANIEL, C., RIVERA, S. Short-run and long-run industry-level estimates of U.S. Armington elasticities. North American Journal of Economics and Finance, v. 14, 2003. GRILLI, E. The European Community and the developing countries. Cambridge: University Press, 1993. HOECKMAN, B., NG, F., OLARREAGA, M. Eliminating excessive tariffs on exports of least developed countries. World Bank Economic Review, v. 16, n. 1, 2002. LAIRD, S., YEATS, A. The UNCTAD trade policy simulation model. UNCTAD Discussion Paper, n. 19, Geneva, UNCTAD, 1986. SKULLY, D. W. Liberalizing tariff-rate quotas. In: BURFISHER, M. E. (ed.). The road ahead: agricultural policy reform in the WTO. Agricultural Economic Report, n. 797, Jan. 2001 TOURINHO, O. A. F., KUME, H., PEDROSO, A. C. S. Elasticidades de Armington para o Brasil: 19862002. Rio de Janeiro: IPEA, August 2003 (Working Paper, 974). 16