Unit 6

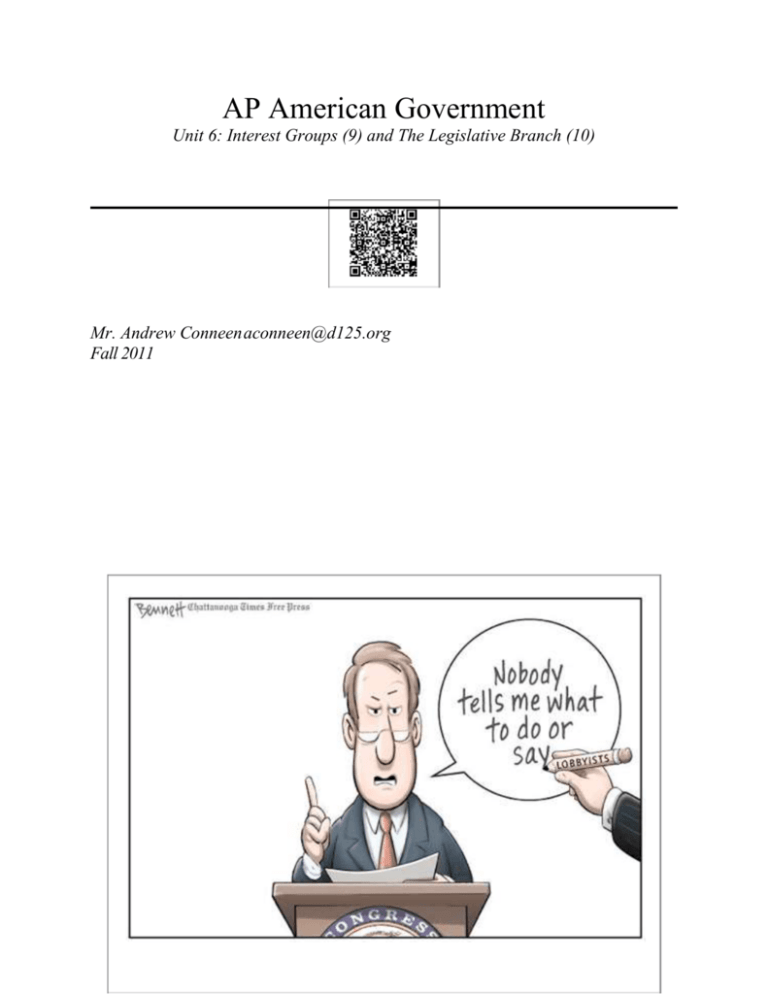

advertisement