Judicial System Basics The U.S. legal system is in part inherited

advertisement

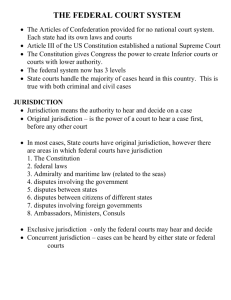

Judicial System Basics The U.S. legal system is in part inherited from English common law and depends on an adversarial system of justice. In an adversarial system, litigants present their cases before a neutral party. The arguments expressed by each litigant (usually represented by lawyers) are supposed to allow the judge or jury to determine the truth about the conflict. Besides presenting written or oral arguments, evidence and testimony are collected by litigants and their lawyers and presented to the court. Litigants usually pay their own attorney’s fees in addition to a $150 -350 fee for filing a civil case in federal court. (Plaintiffs who can’t afford the fee can ask to proceed without paying.) For criminal cases, the government provides a court-appointed attorney for anyone who can’t afford one. Many rules exist regarding how evidence and testimony are presented, trial procedure, courtroom behavior and, etiquette and how evidence and testimony are presented. These rules are designed to promote fairness and allow each side an opportunity to adequately present its case. For federal courts, the rules are determined by committees composed of judges, professors and lawyers appointed by the Chief Justice of the United States. The rules are then approved by the Judicial Conference of the United States and become law unless Congress votes to reject or modify them. State courts and local courts have their own committees and procedural rules, sometimes adapted from the rules for the federal courts. Many judges also have their own rules guiding conduct in their courtrooms. The majority of legal disputes in the U.S. are settled in state courts, but federal courts have considerable power. Many of their rulings become precedent, or a principle, law or interpretation of a law established by a court ruling. Precedent is generally respected by other courts when dealing with a case or situation similar to past precedent. This policy is known as stare decision or “let the decision stand.” Precedent is sometimes overturned or disregarded by a court, but the policy generally provides continuity in courts’ interpretations of the law. Let’s now take a look at the federal court system and why it’s so important. The Federal Court System The Constitution grants Congress power to create and abolish federal courts, although the United States Supreme Court is the only court that cannot be abolished. Congress also has the authority to determine the number of judges in the federal judiciary system. In general, federal courts have jurisdiction over civil actions and criminal cases dealing with federal law. Jurisdiction can overlap, and certain cases which that may be heard in federal court can instead be heard in state court. Federal courts can only interpret the law in the context of deciding a dispute. A court cannot approach an issue on its own or in a hypothetical context. Federal judges, with a few exceptions, are appointed for life -- until they die, retire or resign. The Constitution calls for federal judges to act with “good behavior,” and they can be impeached for improper or criminal conduct. A strict code of conduct exists for federal judges, guiding their behavior. Many judges are also considered scholars in their field and spend time speaking, working in the community, teaching or writing in legal journals. Judges who retire, known as senior judges, may be called up on a full- or part-time basis to help with cases. Senior judges handle 15 percent to 20 percent of the workload for appellate and district courts. Appointed by the President, federal judges are confirmed by the Senate and have their pay determined by Congress. Most federal judges make about the same amount as members of Congress ($150,000 or more), though like some members of Congress, many federal judges have previous experience in more lucrative positions with large law firms. The Constitution doesn’t actually require that judges are lawyers, but so far all federal judges have been members of the Bar trained lawyers. Each federal court has a chief judge who handles some administrative responsibilities in addition to his or her regular duties. The chief judge is usually the judge who has served on that court the longest. Chief justices for district and appeals courts must be under age 65 and may serve as chief judge for seven years but not beyond age 70. Each court also has its own staff of employees, including court reporters, clerks and assistants, who are vital to the operation of the court. A court’s primary administrative officer is the Clerk of the Court, who maintains records, is responsible for the court’s finances, provides support services, sends official notices and summons, administers the jury system and manages interpreters and court reporters. Types of Jurisdiction Earlier in this article, we introduced the notion of jurisdiction. All courts have two types of jurisdiction: subject matter jurisdiction and personal jurisdiction. Let’s go over how these types of jurisdiction work for federal courts. Subject Matter Jurisdiction Subject matter jurisdiction concerns the area of law over which a court has authority. There are two “subsets” of subject matter jurisdiction. Federal Question Jurisdiction Federal courts can decide cases involving disputes under federal law, the U.S. government, conflicts between states or between the U.S. and foreign governments. The case has to raise a “federal question” in order to be heard in federal court. Diversity Jurisdiction A case can be filed in federal court because of a “diversity of citizenship” of the parties involved, meaning that the case involves citizens of different states. Only cases involving more than $75,000 can be filed in federal court, and any diversity jurisdiction case can also be brought in a state court. Personal Jurisdiction Personal jurisdiction is the question of whether a court has authority over an individual or business entity. For example, a court in Vermont cannot make a California resident come to Vermont to defend a lawsuit if he’s never had contact with that state -- either by going to that state, having contact with someone in that state, selling something to a Vermont resident, etc. Similarly, foreigners can’t be made to come to U.S. courts unless the foreigner has had contacts with people in the U.S. relating to the case. Generally, corporations are treated like individuals in federal and state courts. They can sue and be sued. For the purposes of diversity jurisdiction, there are also rules that determine of which state a corporation is a “citizen.” Now that we’ve gone over some of the basics of federal courts and judges, let’s look at the different types of courts, starting with the most important of them all, the Supreme Court of the United States. The Supreme Court of the United States The Supreme Court, which is the only court explicitly created by the Constitution, is the most powerful court in the United States. The Court has nine justices and its decisions cannot be appealed to any other court. For that reason, the Supreme Court is an incredibly powerful and important body, and a nomination of a new justice is an event that attracts significant media attention, debate and even controversy. Thousands of cases are filed with the Supreme Court every year, but the Court only hears 100 to 150 cases a year. Most cases require the Court to interpret an existing law, the intent of Congress when passing legislation, or whether legislation or acts by the Executive are constitutional. The Supreme Court has original jurisdiction in cases involving foreign dignitaries or when the state is a party, meaning that those cases must first be filed in the Supreme Court but may later be passed down to a lower court. All other cases reach the Court on appeal from lower courts. Although Congress has the right to decide how many judges are on the Supreme Court, it can’t change the powers given to the Court by the Constitution. The Judiciary Act of 1789 established the Court with one chief justice and five associate justices. Between 1789 and 1869, the number of justices on the Court changed six times but has remained at nine (eight associate justices and one chief justice) since 1869. The Chief Justice is the “executive officer” of the Court but, like the other justices, has only one vote in deciding cases. In order to decide a case, six justices must vote and a simple majority is all that’s required. When a decision isn’t unanimous, the Court issues majority and minority (or dissenting) opinions. Justices often write separate concurring opinions if they agree with the majority but for different reasons. An opinion is a document that details the justices’ arguments and the reasons behind their decisions. These documents can also contain decisions about the constitutionality of a law or their beliefs about how a law should be interpreted. Opinions comprise a very important part of what’s known as case law, the law created by judges’ written opinions. Case law and precedent set by the Supreme Court are binding on lower courts. They are also used as a guide in the crafting of future legislation by Congress and as case studies by law school students and legal scholars. This statue of former Chief Justice John Marshall, possibly the most influential justice in the Supreme Court's history, is located in John Marshall Park, next to the United States Courthouse. Photo courtesy of United States District Court One of the most important court opinions came in an 1803 case called Marbury v. Madison. Chief Justice John Marshall issued the majority opinion for this case, which established the concept known as judicial review. Although not specified in the Constitution, Chief Justice Marshall used the case as an opportunity to declare that “a legislative act contrary to the Constitution is not law” and that “it is emphatically the province and the duty of the judicial department to say what the law is” [ref]. In this way, he greatly expanded the powers of the Supreme Court. Judicial review has also been used to cover state and local governments. The Court can declare their actions unconstitutional and thereby order them to cease the action in question. The most famous example of judicial review is the landmark 1954 case Brown v. Board of Education. In that case, the Supreme Court declared the Topeka, Kansas school board’s segregation of schools unconstitutional. The decision became part of case law and caused all other segregation laws across the country to be declared unconstitutional. Appeals Courts There are 12 regional Circuit Court of Appeals and one U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit. Created in 1891, the number of judges on each court varies from six to 28, but most have 10 to 15. Each court has the power to review decisions of district courts in its region. Appeals Courts, sometimes called appellate courts, can also review orders of independent regulatory agencies if a dispute remains after the agencies’ internal review processes have been exhausted. Appeal Process A defendant who is found guilty by a criminal court can appeal the ruling to have the case heard by the Court of Appeals. Either side may appeal in a civil case. When the Court of Appeals hears a case, the person appealing the case, called the appellant, must show that the trial court made a legal error that affected the outcome of the case. Each side presents its argument in written documents called briefs to a panel of three judges. The court bases its decision on the record of the case and does not solicit new testimony or evidence. Some panels also allow for short oral arguments. The court’s decision is final unless the case is sent back to the trial court. Someone who loses in Appeals Court can petition for a writ of certiorari, an official request for the Supreme Court to review the case. The Supreme Court is not required to hear the case but generally will if multiple appellate courts have interpreted the law differently, if an important legal principle is at stake or if the case presents an issue relating to how the Constitution is interpreted. or if multiple appellate courts have interpreted the law differently. The Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has national jurisdiction for appeals in specialized cases -- i.e. patent laws or cases decided by courts of special jurisdiction, the Court of International Trade and the Court of Federal Claims. Bankruptcy Appellate Panels Bankruptcy Appellate Panels (BAPs) are panels made up of three judges that hear appeals of bankruptcy court decisions. Considered a unit of the Federal Court of Appeals, BAPs were created and modified by the Bankruptcy Reform Acts of 1978 and 1994. Appellants can appeal decisions by bankruptcy courts with the BAP or a District Court. The following circuits have BAPs: 1st, 6th, 8th, 9th and 10th. District Courts One step below the Court of Appeals is the District Court. Each of the 94 districts has at least two judges; the biggest districts have 24 or more. Each district also has a U.S. bankruptcy court. District Courts are the trial courts of the federal system. Their criminal cases concern federal offenses, and their civil cases deal with matters of federal law or disputes between citizens of different states (remember subject matter jurisdiction). They’re also the only federal courts where grand juries indict the accused and juries decide the cases. Congress determines the court districts based on size, population and case load. Some states have their own district while New York, California and Texas each have four. Judges have to live in the district they serve -- the District of Columbia is the lone exception -- but a judge may temporarily sit in another district to help with a heavy case load. Magistrate Judges Magistrate Judges are appointed by District Judges to serve an eight-year term in a U.S. District Court. Part-time magistrates serve four-year terms. This system was started in 1968 to help District Courts with their caseloads. Both parties involved in a case have to agree to be heard by a Magistrate Judge instead of a District Judge. Magistrate Judges also conduct initial proceedings for cases such as issuing warrants, bail hearings, appointing attorneys and reviewing petitions and motions. A Grand Jury When a U.S. attorney is considering charging someone with a federal crime, he or she convenes a grand jury, made up of 16 to 23 citizens. The grand jury convenes, along with government lawyers, court reporters, interpreters (if necessary) and witnesses, and determines if there’s enough evidence to indict someone, if there’s “probable cause” that the suspect committed the crime. Special Courts Congress has the power to set up special “legislative courts” whose judges are appointed for life terms by the President and approved by the Senate. Today, there are two special trial courts with national jurisdiction. The United States Court of International Trade The U.S. Court of International Trade deals with cases involving international trade and customs. Previously called the United States Customs Court, the court was expanded and its name changed by the Customs Courts Act of 1980. The courtrooms and offices are in New York City, but the Court is also authorized to hold hearings in foreign countries. Appeals of its decisions can be taken to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit and then to the Supreme Court. The judges of the Court of International Trade are sometimes assigned by the chief judge to preside over cases in other parts of the country and like other federal judges, they’re appointed for life. United States Court of Federal Claims The U.S. Court of Federal Claims calls itself “the People’s Court” and deals with most claims for money damages against the U.S. government, disputes over federal contracts, unlawful seizure of private property by the government and other similar claims. The Court began in 1855 as a body that advised Congress on claims against the United States, but in 1863, it became a forum for citizens to file claims against the government. Sixteen judges sit on the Court, and each serves a 15-year term. Other Courts U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims U.S. Tax Court U.S. Court of Military Appeals Military Courts of Review State Courts and Jury Duty Although federal courts are the most powerful courts in the United States and play an essential role in shaping judicial policy and practice, state courts do much of the “grunt” work that keeps our judicial system running. They’re also the courts that Americans are most likely to have contact with in their lives. There are two types of trial courts in most states: special jurisdiction and general jurisdiction. Special jurisdiction courts, which also can be called county, district, justice, justice of the peace, magistrate or police courts, hear the following types of cases: juvenile cases lesser civil and criminal cases traffic-related cases General jurisdiction courts, which also can be called circuit courts, courts of common pleas, superior courts or in the state of New York, the Supreme Court, hear serious civil and criminal cases. All states also have their own appellate courts and a state supreme court. (The 62 trial courts in New York are called Supreme Courts, and the state's highest court is the New York Court of Appeals.)Most states have two types of trial courts: special jurisdiction and general jurisdiction. Special jurisdiction courts hear many traffic violation cases, minor civil disputes, juvenile cases and lesser criminal cases. They are sometimes called district, justice, county, justice of the peace, magistrate or police courts. General jurisdiction courts hear serious criminal and civil cases. General jurisdiction courts are also called circuit courts, court of common pleas, superior courts or in the state of New York, the Supreme Court. All states also have their own appellate courts and a state supreme court. (The 62 trial courts in New York are called Supreme Courts, and the state's highest court is the New York Court of Appeals.) State courts have a variety of systems for how judges attain their positions -- some are appointed by governors, others are elected and have to periodically face reelection. For more information about your state court, check out the National Center for State Courts’ listing of state court Web sites. Jury Duty Jury duty: it’s been a bad Pauly Shore movie and a source of confusion for millions of Americans. But jury duty is also an essential part of our judicial system. If citizens didn’t give up some of their time to serve on juries, conducting fair trials would be almost impossible. Let’s look for a moment at how juries work. As we learned earlier in the article, the U.S. Supreme Court and the Court of Appeals do not use juries. But Federal District Courts, the trial courts of the federal judiciary, do. State trial courts also depend on jurors, who are randomly selected from a pool of registered voters and people with driver’s licenses to ensure a cross-section of the population. Being selected in this way is known as being summoned. A summoned juror must complete a questionnaire to determine if there is any reason that he or she can be disqualified from serving. A jury summons contains instructions that tell the summoned person how to report for jury duty. Being summoned for jury duty does not mean you will automatically have to serve on a jury. However, you will likely have to go to the courthouse and undergo a process called voir dire, where judges and lawyers question potential jurors to determine if they’re fit to serve. People with past experience with the alleged crime, knowledge of either party or who have obvious prejudices may be prevented from serving. Lawyers can also exclude some jurors without giving a reason. There are two types of juries on which private citizens may be called to serve. A trial jury, also known as a petit jury, is made up of six to 12 people for a civil trial and 12 people for a criminal trial. A grand jury, as discussed earlier in the article, is a panel of 16 to 23 people who determine whether there’s “probable cause” to charge someone with a crime.