Chapter 20 Summary

advertisement

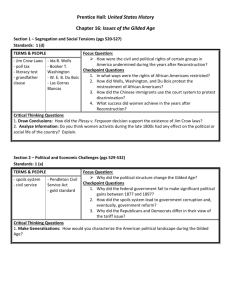

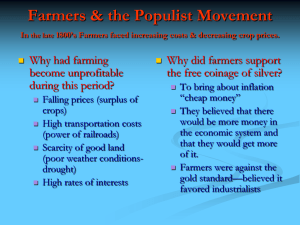

Chapter 20 Summary Introduction This chapter opens with the 1892 gathering of labor and farm leaders along with temperance and woman suffrage advocates in St. Louis, Missouri, that marked the beginning of the Populist Party. Despite their differences, each group looked to the Populist Party for justice within a system that previously had ignored them. Their attempts at political unity and reform moved the United States into a decade of political turbulence, with the Populist Party forcing the laissez-faire government to become more active and involved. The Farmers' Revolt, pp. 710-714 Hard times among farmers during the 1880s and 1890s created the groundswell that became an agrarian revolt. Farmers protested government rules that favored big business, creating new political alliances in the process. The Farmers' Alliance Farm prices dropped decade after decade, railroads charged more for the short haul than the long haul, and southern farmers suffered under the crop lien system. The basic problem was the American banking system, which benefited big business. Among the most important protests was that mounted by the Farmers' Alliance movement. Formed to address growing farm problems, farmers consolidated into two regional alliances—the Northwestern Alliance and the Southern Alliance (which sponsored a separate Colored Farmers' Alliance). At the heart of their message was the harm done to them by the railroads, trusts, and credit merchants. They advocated farmer-owned cooperatives to escape the middlemen who cut into farmers' profits. When cooperatives failed, the alliances realized that they had to make fundamental changes to the American economic system. The Populist Movement Eventually, the Farmers' Alliance became politicized and launched the People's Party and the Populist movement. The movement's supporters promoted ideas like C. W. Macune's subtreasury plan, land reform, government ownership of the railroads, and a cheaper currency. They attempted to draw labor into their ranks by backing the eight-hour workday. And they sought political reforms, including the secret ballot, the direct election of senators, and the initiative and referendum. Their movement presented an alternative vision of American economic democracy. The Labor Wars, pp. 714-723 In the 1890s, industrial workers across the nation waged battle with industry for the right to organize, better working conditions, higher wages, shorter hours, and greater control over the workplace. The ferocity of the conflicts has led historians to call the conflicts the "labor wars." The Homestead Lockout The Homestead strike occurred in 1892 at Andrew Carnegie's Homestead, Pennsylvania, steel mills. The conflict occurred when the Homestead management, led by Carnegie and Henry Clay Frick, attempted to break the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers union by refusing to renew its workers' contracts. The workers, in turn, attempted to keep strikebreakers out of the plant. Inevitably, violence broke out between union workers and Pinkerton guards. Eight thousand National Guardsmen were sent in to protect Carnegie's mills. When an anarchist named Alexander Berkman attempted to assassinate Frick, the strikers lost public sympathy, and the union was destroyed. Carnegie was able to slash wages, reinstitute the twelve-hour workday, eliminate five hundred jobs, and still produce enormous profits even in the midst of the depression. It would take another forty-five years before steelworkers, unskilled as well as skilled, successfully unionized. The Cripple Creek Miners' Strike In 1894, members of the newly formed Western Federation of Miners (WFM) led a strike of mine workers in the gold fields of Cripple Creek, Colorado, to maintain an eight-hour workday. In the midst of armed confrontations between mine owners, who were supported by the county sheriff and his deputies, and the miners, who were supported by local town officials (all members of the WFM), the governor of Colorado was finally called in to settle the conflict. Governor Davis H. Waite was a Populist with strong ties to the miners, and he refused to use the power of the state against the strikers. Unlike those in the Homestead strike, these strikers prevailed, demonstrating the pivotal power of the state, the key role of union organization, and the importance of local support in shaping the outcome of the labor wars. Eugene V. Debs and the Pullman Strike The Pullman strike began at George Pullman's Palace Car Company one year after the disastrous depression of 1893 hit. Pullman's company town provided housing and other amenities for the workers in order to instill loyalty to the company and prevent social unrest and unionization. But company towns controlled everything, including the currency. In short, company towns established social control over their workers while maximizing profits for the company. Unfortunately, Pullman's rents ran 10 to 20 percent higher than housing costs in nearby communities, and Pullman reacted to the depression by cutting wages five times over seven months. Workers rebelled not only because of the wage cuts but also because of Pullman's abusive management tactics and his firing of several American Railway Union (ARU) leaders. A spontaneous strike developed and spread quickly to twenty-seven states and territories, leaving the railroads paralyzed. The strike remained peaceful, even after a federal injunction was issued against it. Eventually, federal troops were brought in to enforce the injunction. Violence erupted immediately, with the leader of the union, Eugene V. Debs, arrested and jailed for contempt of court. Debs's time in jail convinced him to reject unionism and Populism in favor of socialism as the solution to workers' problems. Women's Activism, pp. 723-725 As women organized to deal with the issues that touched their lives, they moved into politics. Two of the most urgent issues of concern were temperance and women's voting rights (suffrage), and among those who worked hardest for these reforms was Frances Willard. Frances Willard and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union Organized in 1874 under Annie Wittenmyer, the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) advocated abstinence from alcohol, arguing that women needed to attack the saloon to protect the home and family from husbands, sons, and brothers who drank away their wages and sometimes subjected their families to violence. With Frances Willard as its president beginning in 1879, the WCTU moved away from a religious approach and viewed alcoholism as a disease; the organization increasingly expanded its activities to address related social problems for the poor and homeless, establishing women's reformatories and sponsoring day nurseries as well as industrial schools for women, medical dispensaries, and lodging houses for the poor. In pursuing temperance, Willard's organization also became a vigorous advocate of woman suffrage. Composed entirely of women, boasting more than 150,000 dues-paying members, the WCTU constituted an important and powerful force for American women. By the 1890s, Willard's leadership had legitimized women's concerns and left the WCTU with a strong legacy of political activism. Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and the Movement for Woman Suffrage Unlike the WCTU, the organized movement for woman suffrage remained small and relatively weak in the late nineteenth century. The women's rights movement, begun by Elizabeth Cady Stanton in Seneca Falls in 1848, split in 1867 over whether the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which granted voting rights to African American men, should have extended the vote to women as well. Stanton and her ally, Susan B. Anthony, launched the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) in 1869, demanding the vote for women. A more conservative group, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), formed the same year. Composed of men as well as women, AWSA believed that women should vote in local but not national elections. By the 1890s, however, the two suffrage organizations resulting from that split had united to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). NAWSA launched campaigns on the state level to gain the vote for women. Successes in Colorado in 1893 and Idaho in 1896 were followed by failure in California in 1896. The ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment—giving women the vote—would take almost three more decades. But the unified suffrage movement and the support of the People's Party and the WCTU positioned women for a growing role in politics and reform. Depression Politics, pp. 725-730 The depression of 1893 lasted more than four years and put almost one of every two laborers out of work. The country swarmed with people looking for jobs. Towns and cities rushed to clamp down on vagrancy by imposing fines and jail terms on the hapless wanderers. The depression's scope made it impossible for local relief agencies to provide effective help. Following the dictates of social Darwinism and laissez-faire politics, most Americans believed that government aid was an inappropriate solution. Yet calls for government intervention increased throughout the 1890s, as the harshness of the depression increased. The Populist Party won widespread support from those backing government intervention as the 1896 election approached. Coxey's "Army" In 1894, masses of unemployed persons marched to Washington to urge Congress for help. The major contingent was led by Jacob S. Coxey of Massilon, Ohio, a millionaire who proposed a plan to build roads using unemployed labor and financed through non-interest-bearing bonds. On May 1, 1894, Coxey and his "army" arrived in Washington, D.C., but quickly were routed; Coxey was arrested and jailed for walking on the grass of the Capitol grounds. His march to Washington was met with trepidation on the part of most Americans, who imagined that revolution and insurrection were not far behind. The movement, although unsuccessful in provoking government aid, dramatized the plight of the unemployed and illustrated how ordinary citizens could influence politics in the 1890s. The People's Party and the Election of 1896 Populists railed against the status quo even before the depression of 1893. Maligned by the eastern press as lunatics and socialists, the People's Party captured one million votes in 1892 and proved to be a powerful force in the election, though the sudden death of its nominee, Leonidis L. Polk, a southerner, its subsequent nomination of former Union general James B. Weaver, and its alliance with African American farmers in the South hurt support from whites in that region. After an even more impressive showing in the 1894 congressional elections, the People's Party readied itself for an electoral showdown with the mainstream parties in 1896. In that year, the Democratic Party split over the issue of free silver, with westerners and southerners repudiating Grover Cleveland because of his support for the gold standard. The Democratic convention nominated the prosilver Nebraska orator William Jennings Bryan. Populists, hoping to displace the Democratic Party in 1896, found themselves fused with the Democrats as they, too, nominated Bryan. The campaign pitted Bryan against the Republican candidate, William McKinley. Backed by industry and its millions of dollars, McKinley campaigned for a gold standard and a high protective tariff. Although the election was close, voters turned out in unprecedented numbers and cast the majority of their votes for McKinley. With Bryan's defeat, the Populists lost their platform, their agrarian revolt, and their party. The United States and the World, pp. 731-734 In the late nineteenth century, Europeans and the Japanese began to construct empires in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific. The United States had a contradictory foreign policy in the 1890s, focusing on both isolationism and expansion. Nonetheless, despite wanting to avoid entanglement in European affairs, Americans also wanted to expand their borders. Commercial expansion and Christian missionary work refocused the nation's attention abroad. Markets and Missionaries The desire for new commercial markets abroad provided an economic impetus for expansion. When American businessmen entered new markets, they expected the government to protect their investments. But business was not the only reason for expansion; there was a moral dimension as well. American Christian missionaries worked to spread the gospel, particularly in China. They met with little success and inspired strong antiforeign attitudes that culminated in the Boxer uprising of 1900 to 1901. The Boxers were an antiforeign society; they eventually terrorized Chinese Christians and missionaries and attacked railroads and telegraphs. Missionaries, besieged for two months in Beijing (then called Peking), demanded protection from the American government, which they received. After routing the Boxers, the troops looted the Forbidden City, home of the imperial court, forcing the Dowager Empress to flee disguised as a peasant. In 1901, the European powers imposed the humiliating Boxer Protocol, giving them the right to maintain military forces in the Chinese capital and requiring the Chinese government to pay an indemnity of $333 million for the loss of life and property resulting from the Boxer uprising. In a commercial and moral alliance of sorts, business interests felt that missionaries paved the way for trade, and missionaries argued that they were fulfilling God's will by enlightening the heathen. The Monroe Doctrine and the Open Door Policy American foreign policy in the late nineteenth century rested on two major statements: the Monroe Doctrine and the Open Door policy. The former declared the Western Hemisphere off-limits to European colonization and set the United States up as its protector. In 1895, the United States risked war with Great Britain over the right to arbitrate a border dispute between Venezuela and British Guiana. The Open Door policy, engineered by Secretary of State John Hay in 1899-1900, established the principle that China would remain free of colonial domination and be equally open to trade with all nations. While inconsistent, both policies were intended to further American economic and political interests. War and Empire, pp. 734-742 The United States did not enter the world stage until 1898, when it went to war with Spain and successfully liberated Cuba. On the surface, the Spanish-American War seemed a contradiction: A war that began in order to ease the suffering of a colonial people ended with the United States becoming a colonial power (over the Philippines) itself. "A Splendid Little War" War with Spain began as a result of a number of issues. Outrage over Spain's treatment of Cuban revolutionaries sparked American concern. Publishers William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer fueled greater interest in Cuba through their sensationalist "yellow journalism" newspaper accounts. To expansionists like Theodore Roosevelt, issues of building a navy and gaining the Philippines as a stepping-stone to trade with China made war with Spain an opportunity not to be missed. In the end, a reluctant President McKinley bowed to pressure for war after an explosion sank the American cruiser Maine, which had been dispatched to Cuba. The war brought Americans together in a show of patriotism. Admiral George Dewey quickly destroyed the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay and grabbed the Philippines from Spain. The American army defeated Spain in a matter of weeks. The war made the political career of Theodore Roosevelt, who had formed his own regiment, the Rough Riders. The Debate over American Imperialism The Spanish-American War left the United States with a far-flung empire. Cuba was not given the full independence it was promised. Instead, the Platt Amendment guaranteed the United States the right to intervene in Cuban affairs. The Treaty of Paris gave the United States control of Puerto Rico and Guam, but what to do with the Philippines was the most pressing problem. The United States paid $20 million for the islands and then had to fight an expensive seven-year war to subdue Filipino revolutionaries who wanted total independence. Critics like William Jennings Bryan argued that expansionism distracted Americans' attention away from domestic problems and provided few benefits. Yet many Americans continued to support imperialism, believing social Darwinism had assured the Anglo-Saxons racial and moral superiority. Conclusion: Rallying around the Flag During the tumultuous decade of the 1890s, the Farmers' Alliance fought for their vision of economic democracy, the Populist Party mounted a serious political challenge to the status quo, workers waged bloody battles against industry, and women fought not only for temperance but also for the right to vote. By decade's end, however, patriotic fervor surrounding the Spanish-American War dominated American life and both the labor movement and the Populists were defeated. Nevertheless, the public increasingly questioned the politics of laissez faire. Calls for greater government involvement in the economy, direct democracy, and a more equitable balance of power between the corporations and the people emerged as themes that would shape American life in the years ahead.