Abbe, Tim - Washington Forest Law Center

advertisement

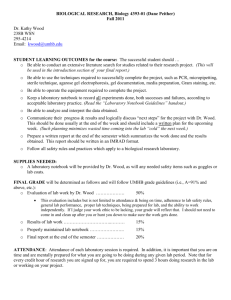

To: From: Date: Re: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service and NOAA Fisheries Tim Abbe, Ph.D. Herrera Environmental Consultants May 11, 2005 FFR is fundamentally flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris. FFR is fundamentally flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris. The FFR1 fails to consider the current low-level of LWD in most channels The DEIS for the FFR clearly points out that “LWD is a key component of fish habitat providing cover and pools, and influencing sediment distribution and storage, forming floodplain and offchannel habitats, and serving as food and habitat for aquatic organisms” (DEIS, p.4-176). “Instream LWD is considered to be one of the most important habitat components lacking in most streams categorized as “not properly functioning” (DEIS, p.4-177). The DEIS goes on to state that “the recovery of instream LWD loads will take decades to centuries” (DEIS, p.4-183). The DEIS goes on to acknowledge that “LWD in streams has been greatly reduced in nearly all streams within the State due to historical logging practices” (DEIS, p.4-176), explaining why “most of the riparian landscape occurring in forested areas appears to not be currently fully functioning” (DEIS, p.4-104). 64% of streams on private forest land identified as “poor” in regards to in-stream large woody debris (WFPA 1999). 78% of all streams on State and private lands in Western Washington are in early seral stage with stem diameters less than 12 inches (WFPB 2000), streams that will take more than 100 years to recover functional LWD recruitment (DEIS, Table 4.7-2., p.4-104). 61% of similar lands in Eastern Washington are in early seral stage will take more than 100 years to recover functional LWD recruitment (DEIS, Table 4.7-2., p.4-104). In reviewing the scientific foundations of the FFR it is also acknowledged that “where riparian stands are dominated by red alder and there is little or no conifer understory, achieving desired future conditions is likely to be delayed for many years beyond the 140-year mature stand target age” (CH2M Hill 2000, p.21-16). The FFR fails to provide assurances that functioning wood levels will be restored in the shortterm through in-stream placement of LWD. The DEIS acknowledges that “in the near-term LWD in streams would continue to decrease, especially in larger streams” under all the alternatives (DEIS, p.4-176). “Along non-fishing 1 Forests and Fish Report supported forest practices and habitat conservation plan. FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 1 bearing streams the amount of LWD would likely reduce (from natural decay and transport) under all alternatives in the short-term” (DEIS, p.4-176) since most of these streams will have no RMZ at all under the proposed rules. The lack of LWD in non-fish bearing channels will reduce the supply of LWD to fish bearing streams downstream. Given the small diameters and dominance of deciduous trees in these immature riparian forests, recruitment would be largely limited to “non functional” wood for most streams and what was functional would be susceptible to high decay rates and low residence times. Because of these facts, any plans to protect endangered species must include active placement of functional wood (FW) into channels deleted in large woody debris to have a reasonable chance of restoring salmonid habitat. The DEIS for the FFR clearly states that it will take from 50 to more than 100 years to restore functional LWD recruitment (“amount of healthy riparian areas”, DEIS, p.4-104) in 99% of State and private lands in Western Washington, and 95% of those in Eastern Washington (those lands subject to Washington Forest Practices Rules, DEIS, Table 4.7-2., p.4-104). These projections are based on optimistic scenarios that ignore flaws in the site potential tree height arguments for RMZ widths put forth by the FFR. The DEIS also notes that full functioning LWD recruitment is also dependent on stream size with regards to recovery time: larger streams require a larger proportion of big trees and more time to recover (DEIS, Table 4.7-2., p.4-104). This admission that the recruitment of FW varies with stream size is supported by the best available science but is not addressed in the FFR. The DEIS notes that active wood placement strategies will be important to meet near-term LWD needs in many fish-bearing streams, but that such actions are “an option” under the proposed alternatives (DEIS, p.4-177). Ninety nine percent of Westside forests and ninety-five percent of Eastside forests (early- to mid-seral riparian stands) “will require active placement to meet adequate LWD levels over the near term (the next 30 or more years)” (DEIS, p.4-177). FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 2 Flawed dependency on site potential tree height (SPTH) of the FFR and unsubstantiated assertions that proposed RMZ buffers will restore natural wood loading The FFR does not take into account channel size in consideration of RMZ widths and uses outdated science with regards to LWD abundance. The FFR cites work by Bilby and Ward (1991) that reported that LWD abundance decreases substantially in larger unmanaged streams (CH2M Hill 2000). But Bilby and Ward (1991) failed to weight LWD quantities to channel size and thus draw inappropriate interpretations since in fact when LWD quantities are measured relative to channel width they consistently increase with channel size (Fox 2001). In the “Review of the scientific foundations of the Forests and Fish Plan” (CH2M Hill 2000, p.2.1-34), it is acknowledged that “the probable amounts of LWD that would be delivered under the Forests and Fish plan would be less than the amount for maximum pool formation.” Given that the vast majority of Washington streams are starting with poor wood loading and little or no potential for recruiting functional wood (due to the early seral stage of riparian forests), even a plan with the objective of attaining amounts of LWD necessary for maximum pool formation would be unlikely to achieve these goals in a reasonable timeframe given initial conditions. Therefore any plan with goals well below the maximum are extremely unlikely to restore and sustain the habitat necessary (in the future) for the survival of endangered salmonids. The SPTH model of wood recruitment is based on studies done at a point in time and did not take into account the relative importance of recruitment processes over decades or centuries. This basic weakness of the SPTH recruitment model (CH2M Hill 2000, p.2.1-4) is never addressed, particularly with regards to bank erosion on streams without CMZs, upslope recruitment (landsliding), and recruitment from upstream source areas (non fish bearing streams) that could be clear cut under the FFR. Failure of the FFR to consider hillslope supply of wood debris in RMZ delineations (wood recruitment from areas not protected as unstable slopes): Stream erosion at the toe of hillslopes is one of the most common mechanisms initiating landsliding. This is not surprising considering that fluvial networks are the principal means of landscape incision and define the lowest topography. Bank erosion can convert a previously stable slope into an unstable slope. In cases where landslides occurred they would certainly deliver wood debris from areas more than 50 feet from the channel (e.g., Benda et al. 2002, 2003; May and Gresswell 2003; Reeves et al. 2003). Such situations are not addressed by the FFR since there is no consideration of the effect of bank erosion on slope stability. Areas that currently appear to have stable banks and hillslopes can not be assumed to remain that way, particularly in areas where sedimentation or inputs of FW could initiate bank erosion. All fluvial networks are subject to fluctuations in sediment supply and/or sediment transport capacity. Large portions of a channel network, particularly most of the lower gradient fish bearing waters, experience changes in their morphology when subjected to these fluctuations. Channels can respond by degradation (incision) or aggradation (sedimentation), both of which typically lead to bank erosion. For example, when a tree falls into a creek it can impound sediment and water, FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 3 forcing flow around the tree and accelerating bank erosion (e.g., Abbe and Montgomery 2003). It is well established in the literature that fluvial networks are subject to periodic disturbances which strongly influence wood loading and channel morphology. (e.g., Bragg 2000; Massong and Montgomery 2000; Lancaster et al. 2001; Benda et al. 2002, 2003; Abbe and Montgomery 2003; May and Gresswell 2003; Montgomery et al. 2003, Reeves et al. 2003). Variations in the magnitude of wood loading and channel change and where and when these changes occur have a significant impact on riparian forests and wood recruitment. To restore and sustain fish habitat any riparian management plan must anticipate the effects of changes in wood loading and channel morphology, particularly in the case of streams starting with little or no functional wood and a history of watershed disturbance. Yet the RMZ guidelines proposed by the FFR establish buffer widths less than the site potential tree height (SPTH) that is widely accepted as the minimum necessary to attain natural wood loading assuming the channel remains constant through time, an assumption invalid for much of a channel network. Once initiated, bank erosion will accelerate FW inputs and trigger even higher bank erosion rates due to elevated water elevations and flow constriction that result from the FW obstructing the channel (e.g., Wolff 1916; Abbe and Montgomery 2003; Church 1992; Luzi 2000). This in turn can over-steepen adjacent hillslopes to trigger landslides which deliver LWD from well outside the 50 ft core zone of the FFR. But under the FFR the effects of bank erosion in triggering landsliding is not considered and therefore a significant upslope supply LWD will be eliminated since “nearly all timber probably would be removed from LWD source areas” (CH2M Hill 2000, p.21-129). Through this process more than 70% of the large wood can come from more than 65 feet from the channel. Under FFR prescriptions most of this source area for FW will be eliminated and decrease wood loading proportionally. These consequences are supported by several studies documenting the importance of landsliding in the delivery of FW. Reeves et al. (2003) found that 65.4% of the large wood in 8.7 km of lower Cummins Creek in the central Oregon Coast Range were from upslope sources, areas above the valley floor, while only 34.6% came from riparian areas adjacent to the channel. Benda et al. (2003) reports that Landslides were responsible for delivering more than 80% of the large wood in Redwood and Olympic National Parks (Benda et al. 2002 and 2003, respectively). The failure of the FFR to understand, explain and incorporate bank erosion as a wood recruitment mechanism into considerations of RMZ widths is clearly apparent in the following statement reported in the “Review of the scientific foundations of the Forest and Fish Plan” (CH2M Hill 2000, p.21-129): “Virtually all of the potential LWD supply would be protected from harvest removal where the combined CMZ and the core-zone widths equal 90 percent or more of the SPTH.” This statement explicitly says that a CMZ width less than the SPTH would be sufficient to ensure all “potential” LWD recruitment occurs. This is a gross mis-understanding of the fact that CMZs can easily be much larger than any SPTH and that the “potential LWD supply” will be a function of the total CMZ width and rate channel migration occurs. To imply that “virtually all potential LWD supply” would be occur with protected buffers of only 90% of the SPTH in the context of FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 4 channel migration is completely unfounded. If a buffer starts at 90% the SPTH (much higher than the actual prescriptions proposed under the FFR), channel migration can reduce LWD inputs by consuming the forest areas within the CMZ and RMZ. After a channel consumes its delineated RMZ it will essentially have no new supply of functional wood and be subject to a severe loss of critical fish habitat. The width of a CMZ is completely independent of the SPTH and concerns where a channel is prone to move in the near-term (next 140 years). The failure of FFR to consider the impacts of precluding RMZ protection to non-fishing bearing streams Non-fish bearing streams have a significant impact on wood recruitment to fish bearing streams. 1. Increase in debris flow frequency due to lack of riparian protection in non-fish headwater channels. 2. Decrease in wood debris quantities delivered downstream Less wood in non-fish bearing headwater channels will decrease the supply to fish bearing channels downstream. 3. In-stream wood and riparian trees in headwater channels (ephemeral and at least half of the perennial non-fish bearing streams which will have no riparian buffers under FFR) tend to slow and diffuse debris flows (e.g., Abbe 2000; Massong and Montgomery 2000; Lancaster et al. 2001). The lack of riparian trees and in-stream logs will result in longer debris flow run-out (Massong and Montgomery 2000; Lancaster et al. 2001), impacting longer distances of fish bearing channels that will be scoured clean of wood by the debris flow. The failure of FFR to properly consider recruitment of wood debris from bank erosion in RMZ delineations. Benda et al. (2003) and Martin and Benda (2001) defined the recruitment distance of trees entering a channel through bank erosion as zero. This definition is valid only for the instant that recruitment occurred and is taken out of context when used to imply that the majority of wood recruitment through time occurs close to the channel. By definition the tree stood some distance from the bank prior to erosion occurring and thus could have been quite some distance away several years earlier. Bank erosion rates are partially dependent on the trees that fall into the channel. If the trees are large enough to act as functional wood (FW), then they will tend to obstruct and deflect flow in the channel. In this process, FW tends to accelerate erosion, even initiating erosion in previously stable banks. Trees that fall into a channel are more likely to initiate bank erosion that will result in more trees entering the channel and so on (Abbe and Montgomery 2003), a fact completely ignored by the FFR. FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 5 Given the current young seral stage of most riparian forests in the state, bank erosion rates are likely to be higher than they would be under future desired conditions necessary to sustain salmonid habitat. Several studies have demonstrated that riparian forests decrease bank erosion rates (Beeson and Doyle 1995; Micheli et al. 2003; Herrera 2005) and that the larger the riparian trees, the lower the erosion rate (Herrera 2005). The role of riparian forest trees on bank erosion and channel changes described earlier have been recognized for sometime (e.g., Wolff 1916; Davidson and Barnaby 1936), but no consideration of these effects are laid out in the FFR. The consequences will mean that the narrow 50 ft core zones prescribed by the FFR will be subject to significant losses in the near term which will in-turn decrease the quantity of functional wood recruited to channels and increase the time necessary to do so beyond what is predicted by FFR. In summary, I believe the FFR is fundamentally flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris to restore and protect the habitat necessary to prevent endangered salmon from going extinct. Sincerely, Tim Abbe, Ph.D. FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 6 Citations in Abbe 2001 4(d) Declaration: Abbe, T.B. 2000. Patterns, mechanics and geomorphic effects of wood debris accumulations in a forest river system. Ph.D. dissertation. University of Washington, Seattle. 220 pp. Abbe, T.B. and D.R. Montgomery. 1996. Large woody debris jams, channel hydraulics, and habitat formation in large rivers. Regulated Rivers: Research and Management 12, 201-221. Allmendinger, N.E., J.E. Pizzuto, T.E. Johnson, W.C. Hession. 2000. The influence of riparian vegetation on channel morphology and lateral migration. EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union 81(19). p. S-254. AFS and SERNW. 2000. Executive Summary: Scientific review of the Washington State Forest & Fish Plan. American Fisheries Society and Society for Ecological Restoration, Northwest Chapter. Batuca, D.G. and J.M. Jordaan, Jr. 2000. Silting and Desilting of Reservoirs. A.A. Balkema. Rotterdam. 353 p. Bilby, R.E. and P.A. Bisson. 1998. Function and distribution of large woody debris. In R. Naiman and R.E. Bilby, Editors. River Ecology and Management Lessons from the Pacific Coastal Ecoregion. Springer-Verlag. New York, 324-346. Bisson, P.A., R.E. Bilby, M.D. Bryant, C.A. Dolloff, G.B. Grette, R.A. House, M.L. Murphy, K.V. Koski, and J.R. Sedell. 1987. Large woody debris in forested streams in the Pacific Northwest: past, present, and future. In Salo, E.O. and T.W. Cundy, Editors. Streamside Management: Forestry and Fishery Interactions. University of Washington Institute of Forest Resources Contribution No.57. Seattle, Washington. 143-190. Bisson, P. A., G. H. Reeves, R. E. Bilby, and R.J. Naiman. 1997. Watershed management and Pacific salmon: Desired future conditions. In: Pacific Salmon and Their Ecosystems: Status and Future Options. Chapman and Hall, New York. Church, M. 1992. Channel morphology and typology. In Calow, P. and Petts, G.E. (Eds), The Rivers Handbook. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 126-143. Davidson, F.A. and Barnaby, J.T. 1936. Survey of Quinault River System and its Runs of Sockeye Salmon. Report to F.T. Bell, Commissioner, U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, 12 p.: Davies, R.J. 1997. Stream channels are narrower in pasture than in forest. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 31, 599-608. FEMAT [Forest Ecosystem Management Assessment Team]. 1993. Forest ecosystem management: an ecological, economic, and social assessment. Report of the FEMAT. U.S. Government Printing Office: 1993-793-071. FFR. 1999. Forest and Fish Report. Washington Forest Protection Association, Office of the Governor of the State of Washington, National Marine Fisheries Service and many others. Presented to the Washington State Forest Practices Board and the Governor’s Salmon Recovery Office. Final Draft February 22, 1999. Olympia, WA. Hartman, G. F., Scrivener, J. C., and McMahon, T. E., 1987, Saying that logging is either "good" or "bad" for fish doesn't tell you how to manage the system: Forestry Chronicle, v. 63, no. 3, p. 159-164. Hicks, B. J., Hall, J. D., Bisson, P. A., and others, 1991, Response of salmonids to habitat changes; Meehan, W. R., editor, Influences of Forest and Rangeland Management on salmonid fishes and their habitats: Bethesda, Maryland, American Fishers Society Special Publication 19. Independent Science Panel. 2000. Review of “Statewide Strategy to Recover Salmon: Extinction is Not an Option.” Independent Science Panel Report 2000-1, May 2000. PO Box 43135, Olympia, WA 98504-3135. NMFS. 1999. Preliminary analysis of riparian conservation measures for the Forest and Fish Report concerning Washington Forest Practices. U.S. Department of Commerce. National Marine Fisheries Service. March 10, 1999. No.357. NMFS. 2000. Statement of how FFR [Forests and Fish Report] likely meets PFC [Properly Functioning Conditions]. Memorandum for: NWR – Will Steele, Regional Administrator. Through: F/NWR3 – Steven W. Landino, Robert A. Turner. From: Mike Parton and Matt Longenbaugh. June 16, 2000. AR 1551. Maser, C., R.F. Tarrant, J.M. Trappe, and J.F. Franklin, Editors. 1988. From the forest to the sea: the story of fallen trees. General Technical Report PNW-229. Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Portland, OR. McHenry, M.L., E. Shott, R.H. Conrad, and G.L. Grette. 1999. Changes in the quantity and characteristics of large woody debris in streams of the Olympic Peninsula, Washington, U.S.A. (1982-1993). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 7 Pollock, M.M. 1999. An assessment of the riparian protection provided in the Forests and Fish Report, and a comparison with riparian protection in other Pacific Northwest Salmonid habitat protection plans – draft. 10,000 Years Institute. Bainbridge, WA. Exhibit 905-BS-1. Prestegaard, K.L. and J.V. LaBranche. 2000. Bankfull channel morphology data on reference streams are not sufficient design criteria for channel restoration in Maryland. EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union 81(19). p. S-263. Prestegaard, K.L. and M. O’Connell. 2000. Controls of stream morphology and stratigraphy on hydrological and biogeochemical processes in riparian zones. EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union 81(19). p. S-255. Rhodes, J.J., D.A. McCullough, and F.A. Espinosa, Jr. 1994. A coarse screening process for potential application in ESA consultations. National Marine Fisheries Service. Portland, OR. Sidle, R. C., Pearce, A. J., and C. L. O'Loughlin, 1985, Hillslope stability and land use, American Geophysical Union, Water Resources Monograph 11, Washington, D.C. Spence, B.C., G.A. Lomnicky, R.M. Hughes, and R.P. Novitzki. 1996. An ecosystem approach to salmonid conservation. Management Technology. TR-4501-96-6057 (“ManTech Report”). Swanson, F.J. and G.W. Lienkaemper. 1978. Physical consequences of large organic debris in Pacific northwest streams. U.S.D.A. General Technical Report PNW-69. Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Exp. Station, Portland, Oregon. 12 p. Sweeney, B.W., T.L. Bott, J.K. Jackson, L.A. Kaplan, J.D. Newbold, L.J. Standley, W.C. Hession, and R.J. Horwitz. 2000. Riparian vegetation, stream geomorphology, and the structure and function of stream ecosystems in Eastern North America. EOS, Transactions of the American Geophysical Union 81(19). p. S-254. Thomson, B. 1991. Annotated bibliography of large organic debris (LOD) with regards to stream channels and fish habitat. MOE Technical Report 32. British Columbia Ministry of the Environment, Victoria, Canada. Trimble, S.W. 1997. Stream channel erosion and change resulting from riparian forests. Geology, v.25, p.467-469. Tschhaplinski, P.J. and G.F. Hartman, 1983, Winter distribution of juvenile coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) before and after logging in Carnation Creek, British Columbia, and some implications for overwinter survival, Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 40, 452-461. Washington Forest Practices Board (WFPB). 2000. Draft Environmental Impact Statement on Alternatives for Forest Practices Rules for: Aquatic and Riparian Resources. March 2000. Olympia, WA. Washington Forest Protection Association (WFPA). 1999. Review of the Scientific Foundations of the Forests and Fish Plan. Consultants report prepared by CH2M Hill for the WFPA. Olympia, WA. New Citations (2005): Abbe, T., Bountry, J., Piety, L., Ward, G., McBride, M. and Kennard, P. 2003. Forest influence on floodplain development and channel migration zones. Geological Society of American Annual Meeting (abstract). November 2-5, 2003. Seattle, WA. Abbe, T.B. and Montgomery, D.R., 2003. Patterns and geomorphic effects of wood debris accumulations in the Queets River watershed. Geomorphology 51, 81-107. Abbe, T.B., Brooks, A., and Montgomery, D.R.. 2003. Wood in river rehabilitation and management, In: Gregory, S.V., Boyer, K.L, and Gurnell, A.M. (Eds.), The Ecology and Management of Wood in World Rivers. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland, pp. 367-389. Abbe, T. B., Fisher, S., and McBride, M., 2001. The effect of Ozette River Logjams on Lake Ozette: Assessing historic conditions and the potential for restoring logjams. Unpublished report submitted to Makah Indian Nation, Neah Bay, WA. Philip Williams & Associates, Ltd., Seattle, WA. Beechie, T.J., Collins, B.D., and Pess, G.R., 2001. Holocene and recent geomorphic processes, land use, and salmonids habitat in two North Puget Sound River basins. In: Dorava, J.M., Montgomery D.R., Palcsak B.B, and Fitzpatrick, F.A., (Eds.), Geomorphic Processes and Riverine Habitat, Water Science and Application Vol. 4. American Geophysical Union, Washington D.C. pp. 85-102. Beeson, C.E. and P.F. Doyle. 1995. Comparison of bank erosion at vegetated and non-vegetated channel bends. Water Resources Bullentin 31(6):983-990. Studied effects of a major flood on bank erosion in four stream reaches in British Columbia, with and without riparian forest. FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 8 Benda, L., Bigelow, P., and Worsley, T.M. 2002. Recruitment of wood to streams in old-growth and second-growth redwood forests, Northern California, U.S.A. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 32(8): 1460-1477. Benda, L., Miller, D., Sias, J., Martin, D., Bilby, R., Veldhuisen, C., and Dunne, T. 2003. Wood recruitment processes and wood budgeting, In: Gregory, S.V., Boyer, K.L, and Gurnell, A.M. (Eds.), The Ecology and Management of Wood in World Rivers. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland, pp. 49-73. Bragg, D.C. 2000. Simulating catastrophic and individualistic large woody debris recruitment for a small riparian system. Ecology 81(5): 1383-1294. Brooks, A.P., G.J. Brierley, R.G. and Millar. 2003. The long-term control of vegetation and woody debris on channel and flood-plain evolution: insights from a paired catchment study in southeastern Australia. Geomorphology 51, 7-30. Brummer, C. J., Abbe, T., Sampson, J.R. and Montgomery, D.R. In Press. Influence of vertical channel change associated with wood accumulations on delineating channel migration zones, Washington, USA. Geomorphology. CH2M Hill. 2000. Review of the scientific foundations of the Forest and Fish Plan. Report prepared for Washington Forest Protection Association. CH2M Hill, Bellevue, WA. April 20, 2000. Collins, B.D. and Montgomery, D.R., 2001. Importance of archival and process studies to characterizing presettlement riverine geomorphic processes and habitat in the Puget Lowland. In: Dorava, J.B., Montgomery, D.R., Palcsak, B., and Fitzpatrick, F. (Eds.), Geomorphic processes and riverine habitat. American Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C., pp. 227-243. Collins, B.D. and Montgomery, D.R., 2002. Forest development, wood jams, and restoration of floodplain rivers in the Puget Lowland. Restoration Ecology 10, 237-247. Collins, B.D., Montgomery, D.R., and Haas, A., 2002. Historic changes in the Distribution and functions of large woody debris in Puget Lowland rivers. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 59, 66-76. Fetherston, K.L. 2005. Pattern and process in mountain river valley forests. Doctoral dissertation. College of Forest Resources, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington. Fox, M.J. 2001. A new look at the quantities and volumes of wood in forested basins of Washington State. M.S. thesis. University of Washington. Seattle, WA. Herrera Environmental Consultants. 2005. Wood debris and bank erosion analysis of the Upper Hoh River. Draft report submitted to Olympic National Park and Bureau of Reclamation. April 16, 2005. Seattle, WA. Lancaster, S.T., Hayes, S.K., and Grant, G.E., 2001. Modeling sediment and wood storage and dynamics in small mountainous watersheds. In: Dorava, J.B., Montgomery, D.R., Palcsak, B., and Fitzpatrick, F. (Eds.), Geomorphic processes and riverine habitat. American Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C., pp. 85-102. Luzi, D.S., 2000. Long-term influence of jams and LWD pieces on channel morphology, Carnation Creek, British Columbia. M.S. Thesis, University of British Columbia. Vancouver, Canada. 198 p. Martin, D. and Benda, L. 2001. Patterns of instream wood recruitment and transport at the watershed scale. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 130: 940-958. Massong, T.M. and Montgomery, D.R., 2000. Influence of sediment supply, lithology, and wood debris on the distribution of bedrock and alluvial channels. Geological Society of America Bulletin 112(5). 591-599. May, C. and Gresswell, R. 2003. Large wood recruitment and redistribution in headwater streams in the southern Oregon Coast Range, U.S.A. Canadian Journal of Forest Resources 33: 1352-1362. Micheli, E.R., J.W. Kirschner, and E.W. Larsen. 2003. Quantifying the effect of riparian forest versus agricultural vegetation on river meander migrations rates, Central Sacramento River, California, USA. River Research and Applications 19:1-12. Montgomery, D.R., Collins, B.D., Abbe, T.B., and Buffington, J.M., 2003. Geomorphologic effects of wood in rivers. In: Gregory, S.V., Boyer, K.L., and Gurnell, A.M. (Eds.), The Ecology and Management of Wood in World Rivers, American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland, pp. 21-47. Montgomery, D.R., Abbe, T.B., Peterson, N.P., Buffington, J.M., Schmidt, K., and Stock, J.D., 1996. Distribution of bedrock and alluvial channels in forested mountain drainage basins. Nature 381, 587-589. Piety, L.A., J.A. Bountry, T.A. Randle, E.W. Lyon. 2004. Geomorphic Assessment of Hoh River in Washington State: River Miles 17 to 40 Between Oxbow Canyon and Mount Tom Creek. U.S Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Technical Service Center, Denver Colorado. Rapp, C.F. and Abbe, T.B., 2003. A Framework for Delineating Channel Migration Zones, Washington State Department of Ecology and Washington State Department of Transportation, Final Draft Publication No. 03-06-027. Olympia Washington. FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 9 Reeves, G., Burnett, K., and McGarry, E. 2003. Sources of large wood in the main stem of a fourth-order watershed in coastal Oregon. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 33: 1363-1370. Simon, A. and A.J.C. Collison. 2002. Quantifying the mechanical and hydrologic effects of riparian vegetation on streambank stability. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 27, 527-546. Wolff, H.H., 1916. The design of a drift barrier across the White River, near Auburn, Washington. Transactions of the American Society of Civil Engineers 16. Paper No.1377, 2061-2085. FFR is flawed with respect to ensuring an adequate supply of functional wood debris 10