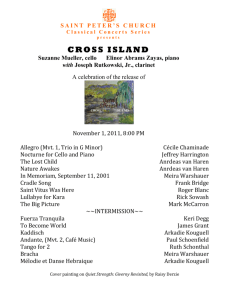

Warner Concert Hall December 11, 2009, 8:00 pm Concert No. 130

advertisement

Contemporary Music Ensemble Timothy Weiss, conductor Milan Vitek, guest conductor Chaya Czernowin, composer-in-residence Steuart Pincombe, cello James Kalyn, soprano saxophone Leah Asher, violin Brendan Shea, violin Warner Concert Hall December 11, 2009, 8:00 pm Concert No. 130 Ritorno degli snovidenia (1976) Luciano Berio (1925–2003) Steuart Pincombe, cello Sarah Pyle, Peng Zhou, Jonathan Figueroa, flute Rachel Messing, Claire Chenette, oboe Brad Cherwin, Ian Copeland, clarinet Paul Deronne, bass clarinet Michael Matushek, Drew Pattison, bassoon Raymond Kelly, saxophone Nicolee Kuester, William Eisenberg, horn Donnie McEwan, Emily Lawyer, trumpet Zachary Guiles, Jacqueline O’Kelly, trombone Jonathan Seiberlich, tuba Danny Walden, piano Marina Kifferstein, Allison Lint, Garrett Openshaw, violin Jane Mitchell, Jesse Yukimura, DJ Cheek, viola Avery Waite, Dylan Messina, Zizai Ning, cello Greg Whittemore, Janie Cowan, bass Clear Sky Josh Levine James Kalyn, soprano saxophone Sarah Pyle, flute Lin Ma, clarinet James Kalyn, saxophone Zachary Guiles, trombone Eugene Kim, piano Ryan Packard, percussion Samantha Bounkeua, violin Jane Mitchell, viola Dylan Messina, cello Greg Whittemore, bass Intermission Anea Crystal (2008) (North American premiere) Seed I Seed II Anea Chaya Czernowin (b. 1957) Quartet I Marina Kifferstein, Garrett Openshaw, violin Jesse Yukimura, viola Zizai Ning, cello Quartet II Samantha Bounkeua, Allison Lint, violin DJ Cheek, viola Dylan Messina, cello Concerto grosso No. 3 (1985) I. Allegro II. Risoluto III. Pesante IV. (Lento) V. Moderato Alfred Schnittke (1934–1998) Milan Vitek, conductor Leah Asher, Brendan Shea, violin Allison Lint, Garrett Openshaw, Samantha Bounkeua, Marina Kifferstein, violin I Lisha Gu, Jenny Elfving, Lisa Goddard, Jing Qiao, violin II Jane Mitchell, Jesse Yukimura, DJ Cheek, viola Avery Waite, Zizai Ning, cello Greg Whittemore, Janie Cowan, bass Zachary Mathes, percussion Miles Fellenberg, piano Danny Walden, harpsichord Nathan Heidelberger, Andrew Ralston, ensemble manager Michael Roest, ensemble manager & librarian Please silence all cell phones and refrain from the use of video cameras unless prior arrangements have been made with the conductor. The use of flash cameras is prohibited. Thank you. Program Notes Ritorno degli snovidenia for solo cello and 30 instrumentalists (1976) by Luciano Berio (Oneglia, Italy, 1925 - Rome, 2003) Instrumentation: cello solo, 3 flutes, 2 oboes, 3 clarinets, alto saxophone, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, tuba, piano, 3 violins, 3 violas, 3 cellos, 2 double basses. Snovidenie (plural snovidenia) means ‛dream’ (literally, ‛the seeing of a dream’) in Russian. The choice of this word has to do with Mstislav Rostropovich, for whom the piece was written, and who played the first performance with Paul Sacher and the Basel Chamber Orchestra on January 20, 1977. Berio disclosed that the ‟dreams” that ‟return” in the work’s title had to do with songs from the October 1917 revolution in Russia -- songs that symbolized a ‟dream betrayed by history.” The songs are never heard in full or, indeed, in any form that is readily recognizable even as a fragment: Berio only used some isolated melodic cells from the songs, and disguised them in such a way that they can never be identified by listening. What one does perceive is a virtuosic solo cello part that is present almost without interruption throughout the entire piece. In the atmospheric opening section, Berio’s precisely notated rhythms have the effect or free rhythm (or tempo fluttuante, sd the composers call it in the score). The meandering cello line is intertwined with similar melodies in the muted trumpet, the bass clarinet, the alto saxophone and other instruments. Gradually, a complex contrapuntal web develops, although the cello always retains its role as the leader. Yet the ‟plot,” and the texture, thickens as more and more tortuous instrumental lines are superimposed on top of one another. The texture is enlivened by nervous repeated-note figures and rapid piano flourishes. Then, surprisingly, we hear an almost literal reprise of the work’s opening but this time, instead of a precisely coordinated tempo fluttuante, an aleatoric passage begins with the instruments repeating their melodic figures independently from one another. In the final ‟stretto,” with the rapid repeated-note figure taking over the entire ensemble, the piano emerges as the soloist’s principal partner, before the work reaches its truly dreamlike ending. ~ Peter Laki Clear Sky, for soprano saxophone and ensemble, is nexus of reflections on my mother's death after over a decade of physical decline. The title refers to the moment itself of her passing when, after days of nearly incessant rain, the clouds broke and sunlight entered the room where she lay. The soloist's part is a strange form of theme-and-variations, where the "variations" are attempts to recover a theme that has been nearly lost. (Consistent with much of my work, a large portion of the piece's melodic and rhythmic material and architecture derive from this germinal theme.) The ensemble is organized into two main groups. Participating in the variations as if in a series of interweaving dreams, the members of the first group—flute, clarinet, trombone, and cello—are like projections of the soloist's most intimate memories. The clarinet has an especially deep connection with the saxophone. The music played by the remaining ensemble instruments is more objective and ritualistic in character, a kind of fragmented, elusive chaconne whose harmonies evolve even as they cycle. Juxtaposed with these musical elements are occasional aural "visions" inspired by the blinding, shimmering reflection of light on bodies of water. Clear Sky was first performed at the 2006 Rümlingen Festival in Switzerland. The saxophone soloist was Marcus Weiss, for whom the part was composed, with the festival ensemble conducted by Peter Rundel. It is dedicated to the memory of Gloria Levine. ~ Josh Levine Anea is an invented name for a music-crystal modeled on an ionic crystal. It is a piece written in three independent and individual movements which can be played separately or together. Seed I and Seed II are for string quartet and Anea is for string octet, being built of both Seeds together played simultaneously with some changes. The pieces belong to the series “Shifting Gravity” together with the pieces Sheva (Seven) and Sahaf (Drift). The five pieces on this series are each a concise and concentrated focus on a singular physical gesture. Close examination of the gesture reveals the strange physical laws of the world in which the gesture exists, and the body performing it. One could conceive of Anea Crystal as an ionic crystal of gestures. Anea Cyrstal is dedicated to Johannes Kalitzke. ~ Chaya Czernowin Concerto grosso No. 3 (1985) by Alfred Schnittke (Engels, Russia, 1934 - Hamburg, 1998) Instrumentation: 2 solo violins, 4 bells, harpsichord (doubling on piano and celesta), strings. Alfred Schnittke would be 75 years old this year; the anniversary is celebrated with concerts, festivals and symposia worldwide. In the Russian-German master’s unique blend of traditionalism and modernism (post-modernism?), the past is destroyed before our very ears, yet it continues to haunt us in strange and utterly unpredictable ways. Schnittke was fascinated with the idea of the Baroque concerto grosso, and wrote a total of six works with that title. The third of these works, in five movements, was composed in 1985, the 300th anniversary year of J.S. Bach’s birth. The opening of the first movement is a clear nod to the Brandenburg Concertos, but strange things start happening almost from the start. The staggered entrances raise the dissonance level, there are more and more distant key changes until -- after an ominous bellstroke -- the tonality becomes completely submerged in a series of chromatic glissandos and the motoric rhythm is obscured by increasingly complex polymeters. The stylistic games continue in the second movement, where Bach’s solo violin works are evoked, similarly distorted in harmony and with some wild dramatic effects. The third movement has less to do with Bach than with the slow movement of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto. Here the austere unisons of the string orchestra receive not one but two different contrasting counterparts: the quiet chordal patterns in the harpsichord and the intense cantilena of the two violins (which begins, incidentally, with a transposed version of the B-A-C-H motif, found in a large number of Schnittke’s works). These three completely different thematic materials ‟fight it out” for most of the movement. Then an intense polyphonic web of the strings (solo and orchestra) takes over, until the bells, once again, put a halt to proceedings. At the beginning of the fourth movement, the harpsichord plays the B-A-C-H motif immediately followed by the motivically related C#-B#-E-D#, the theme the Csharp minor fugue from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I. Another Bach homage gone awry, it is a drawn-out plaintive song that finally (and once more, at the stroke of the bell!) erupts in a desperate cadenza for the two solo violins in free meter, a shock from which the movement never recovers. In the final movement, the keyboard player switches to the celesta, whose magical chords mix with the polytonal arpeggios of the strings (each orchestral player has his or her own line). Later the two soloists enter with a subdued recollection of the first movement’s ‟Brandenburg” material, now a distant memory that gradually fades into silence . ~ Peter Laki